Theory of Incompleteness, from Abstraction to Fragmentation, the Correlation Between Mary Miss' Art and Deconstructivism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2004

HOME Site Search ABOUT US NEWS EVENTS CROSS CORE CUTTING RESEARCH EDUCATION ACTION DISCIPLINES THEMES Inside The Earth Institute a monthly e-newsletter October 2004 Message from Jeff Sachs In the News The Columbia Spectator, October 1, 2004 This fall, the Earth Institute is supporting two new graduate programs: a Masters of Arts in Climate and Society, developed primarily by the International Research Institute for Climate Prediction, and a Ph.D. in Sustainable Development, which will be the first doctoral degree granted by the School of International and Public Affairs. The Discovery Channel, September 27, 2004 Real Video (8:10) Edward Cook, a paleoclimatologist from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, was quoted in this Quicktime Video (8:10) article on research that Lewis and Clark's expedition succeeded in part through favorable climate conditions. The causes and costs of extreme poverty were Earth Institute Receives $4.2 Million discussed by Jeff Sachs and colleagues in a recent Medical News Today, September 21, 2004 Grant to Break Down Barriers and paper published by the Brookings Institute. In his The work of Awash Teklehaimonot, a health expert at e-newsletter video, Jeff stresses the need to use the the Earth Institute, supports the accelerated expansion Increase the Ranks of Women in Earth results of this paper to inform ways to help Africa out of of the health system in Ethiopia. Sciences and Engineering its poverty trap. download Brookings paper The National Science Foundation (NSF) has awarded the The Columbia Spectator, -

Good Chemistry James J

Columbia College Fall 2012 TODAY Good Chemistry James J. Valentini Transitions from Longtime Professor to Dean of the College your Contents columbia connection. COVER STORY FEATURES The perfect midtown location: 40 The Home • Network with Columbia alumni Front • Attend exciting events and programs Ai-jen Poo ’96 gives domes- • Dine with a client tic workers a voice. • Conduct business meetings BY NATHALIE ALONSO ’08 • Take advantage of overnight rooms and so much more. 28 Stand and Deliver Joel Klein ’67’s extraordi- nary career as an attorney, educator and reformer. BY CHRIS BURRELL 18 Good Chemistry James J. Valentini transitions from longtime professor of chemistry to Dean of the College. Meet him in this Q&A with CCT Editor Alex Sachare ’71. 34 The Open Mind of Richard Heffner ’46 APPLY FOR The venerable PBS host MEMBERSHIP TODAY! provides a forum for guests 15 WEST 43 STREET to examine, question and NEW YORK, NY 10036 disagree. TEL: 212.719.0380 BY THOMAS VIncIGUERRA ’85, in residence at The Princeton Club ’86J, ’90 GSAS of New York www.columbiaclub.org COVER: LESLIE JEAN-BART ’76, ’77J; BACK COVER: COLIN SULLIVAN ’11 WITHIN THE FAMILY DEPARTMENTS ALUMNI NEWS Déjà Vu All Over Again or 49 Message from the CCAA President The Start of Something New? Kyra Tirana Barry ’87 on the successful inaugural summer of alumni- ete Mangurian is the 10th head football coach since there, the methods to achieve that goal. The goal will happen if sponsored internships. I came to Columbia as a freshman in 1967. (Yes, we you do the other things along the way.” were “freshmen” then, not “first-years,” and we even Still, there’s no substitute for the goal, what Mangurian calls 50 Bookshelf wore beanies during Orientation — but that’s a story the “W word.” for another time.) Since then, Columbia has compiled “The bottom line is winning,” he said. -

Columbia University in the City of New York Family

FAMILY HANDBOOK COLUMBIACOLUMBIA UNIVERSITY IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK 2009–2010 FAMILY HANDBOOK COLUMBIACOLUMBIA UNIVERSITY IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK Columbia College The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science Dean of Student Affairs Office • Lerner Hall, 6th Floor, 2920 Broadway, New York, NY 10027 • 212-854-2446 http://www.studentaffairs.columbia.edu/parents • e-mail: [email protected] Division of Student Affairs At Columbia University Contents WELCOME FROM THE DEAN OF STUDENT AFFAIRS ................................................................3 2009–2010 ACADEMIC CALENDAR.......................................................................................4 1 Our Campus Community . .5 2 Family Involvement Opportunities . .12 3 Campus Resources . .16 ATHLETICS ........................................................................................................................16 CENTER FOR CAREER EDUCATION.......................................................................................16 CENTER FOR STUDENT ADVISING .......................................................................................18 COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT ...............................................................................................18 COMMUNITY IMPACT..........................................................................................................20 COMPUTING AT COLUMBIA .................................................................................................20 DINING SERVICES ...............................................................................................................20 -

Teachers Have Rights, Too. What Educators Should Know ERIC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 199 144 SO 013 200 AUTHOR Stelzer, Leigh: Banthin, Joanna TITLE Teachers Have Rights, Too. What Educators ShouldKnow About School Law. INSTITUTICN ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/SocialScience Education, Boulder, Colo.: ERIC Clearinghouseon Educational Management, Eugene, Oreg.: SocialScience Education Consortium, Inc., Boulder, Colo- SPCNS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, D.C.: National Inst. of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. DEPORT NO ISBN-0-86552-075-5: ISBN-0-89994-24:.-0 FOB CATE BO CONTRACT 400-78 -0006: 400-78-0007 NOTE 176p. AVAILABLE FPOM Social Science Education Consortium,855 Broadway, Boulder, CO 80802 (S7.95). EDFS PRICE ME01/PCOB Plus Postage. CESCRIPTCPS Academic Freedom: Discipline: *Educational Legislation: Elementary Secondary Education:Ereedom of Speech: Life Style: Malpractice;Reduction in Force: *School Law: Teacher Dismissal:Tenure IDENTIFIERS *Teacher Fights ABSTRACT This book addresses the law-relatedconcerns of school teachers. Much of the datacn which the book is based was collected during a four year stlzdy, conducted bythe American Bar Association with the support of the Ford Foundation.Court cases are cited. Chapter one examines "Tenure." Sincetenure gives teachers the right to their jobs, tenured teachers cannotbe dismissed without due process cf law or without cause. They are entitled to noticeof charges and a fair hearing, with the opportunityto present a defense. The burden is on school authoritiesto show that there are good and lawful reasons for dismissal. "ReductionIn Force (RIF)" is the topic cf chapter two. Many school districtsare facing declining enrollments and rising costs for diminishedservices. EIF begins with a decision that a school district has too many teachers.Laws vary from state to state. -

Namri | Sme Namrc 33

The North American Manufacturing Research Institution of the Society of Manufacturing Engineers invites you to attend the Thirty-third North American Manufacturing Research Conference NAMRC 33 May 24-27, 2005 New York, NY USA Hosted by Columbia University Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, Department of Mechanical Engineering North American Manufacturing Research Institution of the Society of Manufacturing Engineers Dear Colleagues and Friends: We welcome you to the Thirty-third North American Manufacturing Research Conference. NAMRC has been an established international forum for the presentation of cutting-edge research results throughout universities and industries from around the world since 1973. Leaders in manufacturing research have come to this conference to exchange findings and leading edge technological information. Participation in NAMRC 33 provides the authors with far-reaching recognition of their work, as well as yields valuable insight from other leaders in manufacturing research. This year, 77 technical papers will be presented at the conference by researchers from universities, research institutes and industrial research laboratories located around the world. All of these complete manuscripts have been accepted for presentation at NAMRC 33 and published in the Transactions of the conference based on a stringent peer-review process conducted by the Scientific Committee of the North American Manufacturing Research Institution of SME (NAMRI/SME). The conference will begin in the early evening of Tuesday, May 24, with a welcoming reception at the Alfred Lerner Hall, the conference site on Columbia University’s Morningside Campus. On Wednesday, May 25, the conference opening ceremony will feature a keynote address by Michael Idelchik, vice president of the Advanced Technology Program, GE Global Research Center. -

Columbia Blue Great Urban University

Added 3/4 pt Stroke From a one-room classroom with one professor and eight students, today’s Columbia has grown to become the quintessential Office of Undergraduate Admissions Dive in. Columbia University Columbia Blue great urban university. 212 Hamilton Hall, MC 2807 1130 Amsterdam Avenue New York, NY 10027 For more information about Columbia University, please call our office or visit our website: 212-854-2522 undergrad.admissions.columbia.edu Columbia Blue D3 E3 A B C D E F G H Riverside Drive Columbia University New York City 116th Street 116th 114th Street 114th in the City of New York Street 115th 1 1 Columbia Alumni Casa Center Hispánica Bank Street Kraft School of Knox Center Education Union Theological New Jersey Seminary Barnard College Manhattan School of Music The Cloisters Columbia University Museum & Gardens Subway 2 Subway 2 Broadway Lincoln Center Grant’s Tomb for the Performing Arts Bookstore Northwest Furnald Lewisohn Mathematics Chandler Empire State Washington Heights Miller Corner Building Hudson River Chelsea Building Alfred Lerner Theatre Pulitzer Earl Havemeyer Clinton Carman Hall Cathedral of Morningside Heights Intercultural Dodge Statue of Liberty West Village Flatiron Theater St. John the Divine Resource Hall Dodge Fitness One World Trade Building Upper West Side Center Pupin District Center Center Greenwich Village Jewish Theological Central Park Harlem Tribeca 110th Street 110th 113th Street113th 112th Street112th 111th Street Seminary NYC Subway — No. 1 Train The Metropolitan Midtown Apollo Theater SoHo Museum of Art Sundial 3 Butler University Teachers 3 Low Library Uris Schapiro Washington Flatiron Library Hall College Financial Chinatown Square Arch District Upper East Side District East Harlem Noho Gramercy Park Chrysler College Staten Island New York Building Walk Stock Exchange Murray Lenox Hill Yorkville Hill East Village The Bronx Buell Avery Fairchild Lower East Side Mudd East River St. -

Alfred Lerner Hall, Columbia University 28Th

PROGRAM Alfred Lerner Hall, Columbia University 28th - 29th October, 2019 The Alumni Revolution & Alumni Therapy By Daniel Cohen Re-Thinking Alumni Relations in a Digital World Two thought provoking collections of essays dealing with contemporary issues facing alumni relations professionals. Complimentary copies available for Graduway clients and prospects. Email: [email protected] Chris Marshall President Graduway, North America DEAR DELEGATES We are thrilled to host you in bustling standing friendships and cultivate new New York City! and inspiring ones. At the world’s financial and economic An exciting element to the summit epicenter, home to world renowned is GraduwayTV - our official platform Columbia University, Fordham for all GLS (and other) content. If you University and NYU, the spirit of missed a session, or want to listen to entrepreneurial higher education has something that really resonated with thrived for decades. We welcome you, sign up at Graduway.TV and enjoy you to take part in our first Graduway today and beyond. Leaders Summit to be held in New York City and enjoy the many educational Having met hundreds of alumni and professional opportunities that it engagement and career services breeds. professionals in my time, I am grateful for the entrepreneurial spirit of our Our program will provide a forum industry and the opportunities we for us to delve into new ideas, build have to engage with one another. I ourselves and our institutions and raise look forward to an inspiring few days the bar on what it is that we do. It is an together. opportunity for all of us to review best practices, evaluate trends and learn Regards, from the best in the business. -

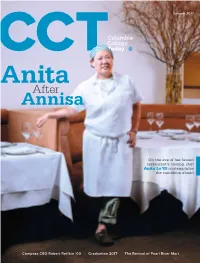

Ccttoday Anita After Annisa

Summer 2017 Columbia College CCTToday Anita After Annisa On the eve of her famed restaurant’s closing, chef Anita Lo ’88 contemplates the transition ahead Compass CEO Robert Reffkin ’00 | Graduation 2017 | The Revival of Pearl River Mart “Every day, I learned something that forced me to reevaluate — my opinions, my actions, my intentions. The potential for personal growth is far greater, it would seem to me, the less comfortable you are.” — Elise Gout CC’19, 2016 Presidential Global Fellow, Jordan Program Our education is rooted in the real world — in internships, global experiences, laboratory work and explorations right here in our own great city. Help us provide students with opportunities to transform academic pursuits into life experiences. Support Extraordinary Students college.columbia.edu/campaign Contents features 14 After Annisa On the eve of her famed restaurant’s closing, chef Anita Lo ’88 contemplates the transition ahead. By Klancy Miller ’96 20 “ The Journey Was the Exciting Part” Compass CEO Robert Reffkin ’00, BUS’03 on creating his own path to success. By Jacqueline Raposo 24 Graduation 2017 The Class of 2017’s big day in words and photos; plus Real Life 101 from humor writer Susanna Wolff ’10. Cover: Photograph by Jörg Meyer Contents departments alumninews 3 Within the Family 38 Lions Telling new CCT stories online. Joanne Kwong ’97, Ron Padgett ’64 By Alexis Boncy SOA’11 41 Alumni in the News 4 Letters to the Editor 42 Bookshelf 6 Message from Dean James J. Valentini High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist The Class of 2017 is a “Perfect 10.” and the Making of an American Classic by Glenn Frankel ’71 7 Around the Quads New Frank Lloyd Wright exhibition at MOMA 44 Reunion 2017 organized by Barry Bergdoll ’77, GSAS’86. -

City College in the Popular Imagination Philip Kay Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

‘Guttersnipes’ and ‘Eliterates’: City College in the Popular Imagination Philip Kay Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK 2011 © 2011 Philip Kay All rights reserved (This page intentionally left blank) ABSTRACT ‘Guttersnipes’ and ‘Eliterates’: City College in the Popular Imagination Philip Kay Young people go to college not merely to equip themselves for competition in the workplace, but also to construct new identities and find a home in the world. This dissertation shows how, in the midst of wrenching social change, communities, too, use colleges in their struggle to reinvent and re-situate themselves in relation to other groups. As a case study of this symbolic process I focus on the City College of New York, the world’s first tuition-free, publicly funded municipal college, erstwhile “Harvard of the Poor,” and birthplace of affirmative action programs and “Open Admissions” in higher education. I examine five key moments between 1940 and 2000 when the college dominated the headlines and draw on journalistic accounts, memoirs, guidebooks, fiction, poetry, drama, songs, and interviews with former students and faculty to chart the institution’s emergence as a cultural icon, a lightning rod, and the perennial focus of public controversy. In each instance a variety of actors from the Catholic Church to the New York Post mobilized popular perceptions in order to alternately shore up and erode support for City College and, in so doing, worked to reconfigure the larger New York public. -

Disability Access Map (Morningside)

columbia University in the city of new york CAMPUS SECTION see Inset A To Teachers College Inset A: East of Amsterdam Ave., North of 120th St. Schapiro CEPSR Pupin Plaza NW Corner Building Y To Barnard College Avery LIBRAR Plaza W 7 LO 4 Schapiro CEPSR Pupin Plaza 18 UPPER CAMPUS NW Schapiro Corner Building CEPSR LOWER CAMPUS Pupin Plaza NW Corner Building UPPER CAMPUS Low Plaza LOWER CAMPUS Avery Pulitzer Plaza (Journalism) 7 ispánica H Avery 4 Plaza 7 ELEVATION 18 4 18 Low Plaza Inset B: West of Broadway, South of 116th Street 2 Pulitzer Low Plaza (Journalism) ispánica H see Inset B Pulitzer (Journalism) ispánica H 2 3 Nussbaum Alumni Center 2 E 3 Nussbaum N Alumni Center K W E E S 3 Nussbaum E E MAP KEY Alumni Center ACCESSIBLE CAMPUS ROUTE INFORMATION E Accessible Campus Entrance Accessible Building Entrance Requiring Columbia University To access Upper Campus: Identification (CUID) swipe access at • From 116th Street and Broadway, use Dodge elevator located K all times— K on College Walk, west of Low Plaza E AccessibleE Building Entrance Prior authorization required • Via Kent Hall, enter Kent through College Walk entrance and Restricted Access Elevator— E Prior authorizationK or assistance from exit building on 3rd floor (accessible during business hours E Building Elevator Public Safety required Monday–Friday; call 212-854-2797 to confirm hours) Wheelchair Lift— • Via Schapiro/CEPSR Hall, enter 120th Street entrance of Ramp Prior authorization or assistance from Schapiro/CEPSR Hall between Broadway and Amsterdam E Public Safety -

Internguide 05-24-2004.Qxd

Columbia University Housing and Dining Intern Guide Summer 2004 Welcome! FlexAccount Welcome to summer in East Campus! This Guide will provide you Need to do laundry or want to satisfy a candy craving but can’t find with information about living at Columbia. If you have further a quarter for the machine? FlexAccount to the rescue! Your questions, please visit FlexAccount is a declining balance system you can access with your www.columbia.edu/cu/reshalls/summerhsg/intern-nycwork, or Columbia Card. You may use your FlexAccount Dollars for vending contact Housing and Dining at [email protected]. machines, game room tokens, laundry (see below) and the Summer Resident Assistants Columbia Bookstore. Your FlexAccount will be set up with a complimentary $10 initial deposit when you arrive. You may add Your Resident Assistant (RA) serves as a liaison between you and value to your account by credit card, cash or traveler’s check at the Housing and Dining, and enforces building policy. He or she will Hospitality Desk, which is located in the Hartley lobby. also act as an informational resource. Contact him/her with questions about life in East Campus. Laundry Name Room Ext. Nathan Bliss H303D 3-5184 There’s no excuse for grungy clothing -- laundry facilities are Christine Hvlaka H506A 3-5252 available in the basement of East Campus. Wash and dry cost $1 Alexander Rikun H404B 3-5218 each, and you may pay with either coins or your FlexAccount. Sean Kelly H601A 3-2349 Laundry product vending machines are also available in each Joseph Hahn 801A 3-4754 facility. -

Download This Issue As A

Columbia College Spring 2015 TODAY Food, Glorious Food Contents FOOD, GLORIOUS FOOD 20 Students Bond Around 24 Overheard in Ferris Food Booth Commons Clubs, communities and other initiatives An illustration of the undergraduate eating based around food offer students a chance experience. to connect. BY KARL DAUM ’15 BY NATHALIE ALONSO ’08 26 Epicures and 37 So Where Do You Want Entrepreneurs to Eat? Alumni follow their passions and build Alumni of all ages recall their favorite careers in all aspects of the food industry. dining choices in Morningside Heights. BY ALEX SACHARE ’71 14 48 54 MESSAGE FROM DEAN JAMES J. VALENTINI Food Makes for Good Chemistry hirty-two years ago, upon my very first visit to Columbia, my hosts in the chemistry depart- ment took me for dinner to Fencing wins titles Pippa Murray ’96 Darryl Pinckney ’88 Moon Palace, on Broadway between West 111th and 112th TStreets. The Shanghai-style Chinese restaurant, located next to Bank Street Bookstore, was a DEPARTMENTS favorite in the neighborhood for students and WEB EXTRAS faculty — especially chemistry faculty, who 3 Message from Dean James J. Valentini took speakers there every Thursday after the Food makes for good chemistry. Kailee Pedersen ’17 department seminar. The restaurant closed reads her award- eight years later, in 1991, only days before I 4 Letters to the Editor winning poetry returned to campus as a professor. It had been a Morningside Heights institution for 26 years. 5 Within the Family by Editor Alex Sachare ’71 Recipes from In the years since, new eateries in the neigh- Creating a food-themed issue of CCT.