Danto and His Critics: After the End of Art and Art History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art

DIVIDED ART GALLERY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA WORLDS 2018 ADELAIDE BIENNIAL OF AUSTRALIAN ART The cat sits under the dark sky in the night, watching the mysterious trees. There are spirits afoot. She watches, alert to the breeze and soft movements of leaves. And although she doesn’t think of spirits, she does feel them. In fact, she is at one with them: possessed. She is a wild thing after all – a hunter, a killer, a ferocious lover. Our ancestors lived under that same sky, but they surely dreamed different dreams from us. Who knows what they dreamed? A curator’s dream DIVIDED WORLDS ART 2018 GALLERY ADELAIDE OF BIENNIAL SOUTH OF AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIAN ERICA GREEN ART ARTISTS LISA ADAMS JULIE GOUGH VERNON AH KEE LOUISE HEARMAN ROY ANANDA TIMOTHY HORN DANIEL BOYD KEN SISTERS KRISTIAN BURFORD LINDY LEE MARIA FERNANDA CARDOSO KHAI LIEW BARBARA CLEVELAND ANGELICA MESITI KIRSTEN COELHO PATRICIA PICCININI SEAN CORDEIRO + CLAIRE HEALY PIP + POP TAMARA DEAN PATRICK POUND TIM EDWARDS KHALED SABSABI EMILY FLOYD NIKE SAVVAS HAYDEN FOWLER CHRISTIAN THOMPSON AMOS GEBHARDT JOHN R WALKER GHOSTPATROL DAVID BOOTH DOUGLAS WATKIN pp. 2–3, still: Angelica Mesiti, born Kristian Burford, born 1974, Waikerie, 1976, Sydney Mother Tongue, 2017, South Australia, Audition, Scene 1: two-channel HD colour video, surround In Love, 2013, fibreglass reinforced sound, 17 minutes; Courtesy the artist polyurethane resin, polyurethane and Anna Schwartz Gallery Melbourne foam, oil paint, Mirrorpane glass, Commissioned by Aarhus European Steelcase cubicles, aluminium, steel, Capital of Culture 2017 in association carpet, 261 x 193 x 252 cm; with the 2018 Adelaide Biennial Courtesy the artist photo: Bonnie Elliott photo: Eric Minh Swenson DIRECTOR'S 7 FOREWORD Contemporary art offers a barometer of the nation’s Tim Edwards (SA), Emily Floyd (Vic.), Hayden Fowler (NSW), interests, anxieties and preoccupations. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnadon Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 A CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPOEU^.RY IRAQI ART USING SIX CASE STUDIES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mohammed Al-Sadoun ***** The Ohio Sate University 1999 Dissertation Committee Approved by Dr. -

Diss Final 4.04.11

Senses of Beauty by Natalie Michelle Carnes Graduate Program in Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Stanley Hauerwas, Supervisor ___________________________ Jeremy Begbie ___________________________ Elizabeth Clark ___________________________ Paul Griffiths ___________________________ J. Warren Smith Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v ABSTRACT Senses of Beauty by Natalie Michelle Carnes Graduate Program in Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Stanley Hauerwas, Supervisor ___________________________ Jeremy Begbie ___________________________ Elizabeth Clark ___________________________ Paul Griffiths ___________________________ J. Warren Smith An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Natalie Carnes 2011 Abstract Against the dominant contemporary options of usefulness and disinterestedness, this dissertation attempts to display that beauty is better—more fully, richly, generatively—described with the categories of fittingness and gratuity. By working through texts by Gregory of Nyssa, this dissertation fills out what fittingness and gratuity entail—what, that is, they do for beauty-seekers and beauty-talkers. After the historical set-up of the first chapter, chapter 2 considers fittingness and gratuity through Gregory’s doctrine of God because Beauty, for Gregory, is a name for God. That God is radically transcendent transforms (radicalizes) fittingness and gratuity away from a strictly Platonic vision of how they might function. Chapter 3 extends such radicalization by considering beauty in light of Christology and particularly in light of the Christological claims to invisibility, poverty, and suffering. -

Brillo: Is It Art?

Brillo: Is It Art? Andy Warhol, Brillo Soap Pads Box, 1964, © AWF © The Andy Warhol Museum, one of the four Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. All rights reserved. You may view and download the materials posted in this site for personal, informational, educational and non-commercial use only. The contents of this site may not be reproduced in any form beyond its original intent without the permission of The Andy Warhol Museum. except where noted, ownership of all material is The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Brillo: Is It Art? Andy Warhol, Brillo Box (3¢ Off), 1963-1964, © AWF © The Andy Warhol Museum, one of the four Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. All rights reserved. You may view and download the materials posted in this site for personal, informational, educational and non-commercial use only. The contents of this site may not be reproduced in any form beyond its original intent without the permission of The Andy Warhol Museum. except where noted, ownership of all material is The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Brillo: Is It Art? An example of the tastes and biases web worksheet, filled out with thoughts related to Warhol's Silver Clouds. © The Andy Warhol Museum, one of the four Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. All rights reserved. You may view and download the materials posted in this site for personal, informational, educational and non-commercial use only. The contents of this site may not be reproduced in any form beyond its original intent without the permission of The Andy Warhol Museum. -

Aesthetic Play and Bad Intent

Article Aesthetic Play and Bad Intent Andrew J. Kerr† Threatening words or images are assumed by American courts to be non-art. But this threshold question of art status is complicated by the evolution of rap and performance art. There is no articulable way to discern art from non-art for these non- textual media, a problem compounded in the unique context of the Internet. In civil litigation we can resort to institutionalist tests like audience reception. But mens rea matters in criminal prosecution. I favor judicial pragmatism in what I argue here is a very non-legal area of law. I. INTRODUCTION In March 2016, Compton rapper YG released the single, “FDT”, shorthand for “fuck Donald Trump,” as a critical response to the then Republican primary challenger. The track was rec- orded in about an hour,1 and eventually became a summer an- them because of its political appeal.2 VICE Media’s Noisey pub- lication celebrated it as the best track of 2016. Some of the lyrics are rote and predictable. Still, it possesses a vital energy and contains several clever lines, such as the couplet: “Reagan sold coke / Obama sold hope.”3 Any rap fan would recognize the song † Lecturer of Legal English, Georgetown University Law Center. I thank Robin West, Alexa Freeman, Sonya Bonneau, and Xiangyu Zhang for their help- ful comments, as well as the organizers and participants of the 2017 Law and Literature conference at Masaryk University for their formative feedback on this project. Copyright © 2018 by Andrew J. Kerr. 1. Adelle Platon, YG & Nipsey Hussle Discuss Their Anti-Donald Trump Track ‘FDT’ & Why ‘Trump Is Not the Answer’, BILLBOARD (Apr. -

Film Culture in Transition

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art ERIKA BALSOM Amsterdam University Press Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Erika Balsom This book is published in print and online through the online OAPEN library (www.oapen.org) OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative in- itiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic research by aggregating peer reviewed Open Access publications from across Europe. Sections of chapter one have previously appeared as a part of “Screening Rooms: The Movie Theatre in/and the Gallery,” in Public: Art/Culture/Ideas (), -. Sections of chapter two have previously appeared as “A Cinema in the Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins,” Screen : (December ), -. Cover illustration (front): Pierre Bismuth, Following the Right Hand of Louise Brooks in Beauty Contest, . Marker pen on Plexiglas with c-print, x inches. Courtesy of the artist and Team Gallery, New York. Cover illustration (back): Simon Starling, Wilhelm Noack oHG, . Installation view at neugerriemschneider, Berlin, . Photo: Jens Ziehe, courtesy of the artist, neugerriemschneider, Berlin, and Casey Kaplan, New York. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: JAPES, Amsterdam isbn e-isbn (pdf) e-isbn (ePub) nur / © E. Balsom / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Sunday Morning Grid 1/21/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

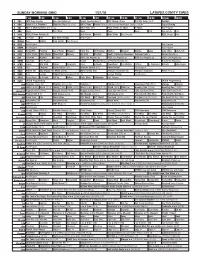

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/21/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Sports Spectacular (N) NFL Champ. Chase The NFL Today (N) Å Football 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Hockey Philadelphia Flyers at Washington Capitals. (N) Å Figure Skating 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Huell’s California Adventures: National Parks Å Vibrant for Life Å 30 ION Jeremiah Michael In Touch NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

New Waves in Aesthetics

New Waves in Aesthetics Edited by Kathleen Stock and Katherine Thomson-Jones New Waves in Aesthetics June 21, 2008 10:20 MAC/NWA Page-i 9780230_220478_01_prexx New Waves in Philosophy Series Editors: Vincent F. Hendricks and Duncan Pritchard Titles include: Jan Kyrre Berg Olsen, Evan Selinger and Søren Riis (editors) NEW WAVES IN PHILOSOPHY OF TECHNOLOGY Vincent F. Hendricks and Duncan Pritchard (editors) NEW WAVES IN EPISTEMOLOGY Thomas S. Petersen, Jesper Ryberg and Clark Wolf (editors) NEW WAVES IN APPLIED ETHICS Kathleen Stock and Katherine Thomson-Jones (editors) NEW WAVES IN AESTHETICS Forthcoming: Yujin Nagasawa and Erik Wielenberg (editors) NEW WAVES IN PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION Boudewijn DeBruin and Christopher Zurn (editors) NEW WAVES IN POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY Future Volumes New Waves in Philosophy of Science New Waves in Philosophy of Language New Waves in Philosophy of Mathematics New Waves in Philosophy of Mind New Waves in Meta-Ethics New Waves in Ethics New Waves in Metaphysics New Waves in Formal Philosophy New Waves in Philosophy of Law New Waves in Philosophy Series Standing Order ISBN 978–0–230–53797–2 (hardcover) Series Standing Order ISBN 978–0–230–53798–9 (paperback) (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. Please contact your bookseller or, in case of difficulty, write to us at the address below with your name and address, the title of the series and the ISBN quoted above. Customer Services Department, Macmillan Distribution Ltd, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS, England June 21, 2008 10:20 MAC/NWA Page-ii 9780230_220478_01_prexx New Waves in Aesthetics Edited by Kathleen Stock and Katherine Thomson-Jones June 21, 2008 10:20 MAC/NWA Page-iii 9780230_220478_01_prexx Selection and editorial matter © Kathleen Stock and Katherine Thomson-Jones 2008 Chapters © the individual authors All rights reserved. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: [email protected] PETER YOUNG Ellipse Paintings ARTIST’S FIRST SOLO EXHIBITION AT GALLERY WENDI NORRIS September 8 – October 29, 2016 Opening Reception: Thursday, September 8, 6-8PM Peter Young in conversation with Gary Garrels, Elise S. Haas Senior Curator of Painting & Sculpture, SFMOMA Wednesday, September 28, 6-7PM #36 – 1994, 1994, Acrylic on canvas, 67 3/4 x 80 1/2 inches (172.1 x 204.5 cm) July 5, 2016 – San Francisco – For the first exhibition with Peter Young, Gallery Wendi Norris will exhibit nine large paintings on canvas and eight small paintings on paper from the artist’s “Ellipse” series. The solo show will encompass the entire gallery with works completed between 1989-2001. Charisma and exuberance flow through the gestural color swatches in Young’s work. In works like #75- 2000 and #76-2000, the central color palette is that of primary colors, and in others, such as #36-1994, the softer hues of western landscapes appear. For example, in #36-1994, the sienna glow of the rocky environs surrounding his Southern Arizona home is prominent, with thinly washed turquoise strokes, suggesting the pristine blue skies of the desert. Though the foreground is made up of flat, thickly colored geometric shapes, the background is comprised of delicate washes of acrylic or vacant white canvas. Such distinct layers produce a surprising sense of depth and motion as the viewer’s eye moves from one plane to the other. A dancing effect materializes and the works approach the near figurative, as if in conversation with paintings of an earlier era with a similar emphasis on joie-de-vivre, perhaps those of Matisse and his fauvist compatriots. -

Exhibition Advisory

^ Exhibition advisory Exhibition: Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959–1971 On View: March 19–September 10, 2017 Location: Resnick Pavilion (Image credits on page 6) (Los Angeles—March 6, 2017) The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959–1971, an examination of the storied history of Dwan Gallery, one of the most important galleries of the postwar period in the United States. Virginia Dwan (b. 1931), gallery owner, art patron, and collector, was one of the greatest champions of avant-garde art and artists of the mid-20th century. During her more than 11 years as a gallerist, Dwan’s Los Angeles and New York galleries were among the first bicoastal spaces dedicated to showcasing contemporary art in America. As an arts patron, Dwan was a pivotal figure in the Los Angeles art scene, often providing artists with stipends, studio space, and housing, in addition to giving many artists their first solo shows. At the time, the exhibitions presented at Dwan Gallery were at the forefront of postwar avant-garde art. Dwan organized one of the first Pop art exhibitions in the United States, My Country ’Tis of Thee (1962), and she was one of the earliest and most ardent supporters of Minimal Art and Earthworks. Founded in 1959, Dwan Gallery first opened in a storefront in Westwood, Los Angeles. The gallery presented groundbreaking exhibitions of New York artists such as Philip Guston, Franz Kline, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, Ad Reinhardt, and Larry Rivers as well as the Los Angeles-based artist Edward Kienholz. -

Artmargins 5(3): "Art Periodicals, Historically Considered"

INTRODUCTION: ART PERIODICALS TODAY, HISTORICALLY CONSIDERED octaVian es¸anu and angela harutyunyan Immanuel Kant’s answer to the question “What Is Enlightenment?” was not only a call to exercise reason, but also to have the courage to do so publicly. It was no accident, then, that Kant’s Sapere aude! (“Dare to be wise!” or “Dare to know!”) appeared in the pages of the Berlin peri- odical Berlinische Monatsschrift in 1784.1 Periodical print culture is the true product of the modern age, born out of an urgent need to advance the idea of freedom and its universal application. Print periodicals turned into a battleground where words replaced swords and where skirmishes were fought over a wide range of issues and obstacles that were thought to hinder the way of universal progress toward greater autonomy and justice. The term periodical—which implies duration and iteration, but also pauses, or “writing in time” as in the German Zeitschrift —is suggestive of a temporality punctuated by short inter- vals during which the conditions of autonomy of the modern subject are renegotiated. Art periodical magazines, journals, reviews, and quarterlies yield to the same historical necessity of bringing artistic, cultural, social, 1 Immanuel Kant, “An Answer to the Question: What Is Enlightenment?” Berlin Monthly (December 1784). Translating the phrase from Horace, Kant deployed sapere aude as his motto for the Enlightenment. © 2016 ARTMargins and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology doi:10.1162/ARTM_a_00155 3 and political phenomena to public light, of questioning the obvious, and of keeping power in check. Art periodicals were born out of the contradictions of capitalism and the constant urge to revolutionize the means of production. -

(26.11.2018) Pop

CLAES OLDENBURG’S STORE, 1961 Jim Dine, Five feet of colorful tools, 1962 Roy Lichtenstein, Brushstroke, 1965 James Rosenquist Smoked glass 1962 Andy Warhol, Marylin, 1962 The Stable gallery opening, New York, 1963 In December 1963, Andy Warhol ordered a large number of pine boxes from the Havlicek Woodworking Company. These were destined to be used in the first project in his new studio, dubbed the Factory, which would be presented in his first ever sculpture show. In the early months of 1964, Warhol and his helpers would screen print the labels of famous consumer products on each box, creating facsimiles of the originals: Campbell's tomato juice, Del Monte peach halves, Heinz ketchup, Kellogg's cornflakes, Mott's apple juice, and, of course, Brillo pads. The Brillo boxes (there was both a yellow version and the iconic white) were the most memorable, and, with the earlier Campbell's soup lithos, count among of the most famous images in Warhol's oeuvres. Stacked in piles at New York's Stable Gallery, these boxes would help catapult Warhol into superstardom, and Brillo would become emblematic of that ascent. http://www.artbouillon.com/2013/02/that-brilliant-brillo-box-pops-debt-to.html "New Realists Exhibition," Sidney Janis Gallery, 1962 Andy Warhol, Do it yourself (by-the- numbers), 1962 Jasper Johns, Three Flags, 1958 La luce del Pensiero di Mao Zedong illumina la strada della Grande Rivoluzione Culturale Proletaria, 1966, stampa, 53.5 x 74 cm, collezione Ziyunxuan, pubblicità Campbell ani sessanta Andy Warhol, Cambell soup cans, 1962 Andy Warhol Orange Car Crash Fourteen Times 1963 Green Car Crash.