Bulletin July 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article

SGA200171.qxp 3/24/11 1:50 PM Page 158 Abstracts SGNA’S 38TH ANNUAL COURSE May 6-11, 2011 | Indianapolis, Indiana WE ARE PLEASED TO PRESENT THE ABSTRACTS FROM SGNA’S 38TH ANNUAL COURSE, SGNA: THE LINK BETWEEN PRACTICE AND CARE. THE DIVERSITY OF THESE TOPICS CERTAINLY REFLECTS THE RICHNESS AND BREADTH OF OUR SPECIALTY.IN KEEPING WITH THE TRADITION OF THE ANNUAL COURSE, WE HOPE THE FOLLOWING ABSTRACTS WILL ENCOURAGE DISCUSSIONS FOR IMPROVING NURSING PRACTICE AND PATIENT CARE OUTCOMES. Kathy A. Baker, PhD, RN, ACNS-BC, CGRN, FAAN Editor TRAIN THE TRAINER: THE NURSE quality of care and patient safety; and a growing need MANAGER’S GUIDE TO THE REPROCESSING COMPETENCY to solve the fiscal dilemma of meeting the significant care demands of the patients we serve are just some of Jane Allaire, RN, CGRN the drivers for improved performance. In an effort to James Collins, BS, RN, CNOR improve efficiency, numerous facilities have begun to Michelle E. Day, MSN, RN, CGRN use Lean methods. These methods have been successful Cynthia M. Friis, MEd, BSN, RN, BC in eliminating waste and redundancy in endoscopy work processes resulting in improved financial, patient Patricia Maher, RN, CGRN satisfaction, and safety performance. Identifying the Joan Metze, BSN, RN waste, creating standard work processes, and using data which also serve as benchmarks will provide a The process for reprocessing flexible gastrointestinal baseline for the implementation of Lean methods. An endoscopes, as outlined by the Society of important part of implementing new processes in the Gastroenterology Nurses and Assocciates, will be thor- gastrointestinal unit is facilitating the change process. -

Evaluation of Nipple Discharge

New 2016 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Evaluation of Nipple Discharge Variant 1: Physiologic nipple discharge. Female of any age. Initial imaging examination. Radiologic Procedure Rating Comments RRL* Mammography diagnostic 1 See references [2,4-7]. ☢☢ Digital breast tomosynthesis diagnostic 1 See references [2,4-7]. ☢☢ US breast 1 See references [2,4-7]. O MRI breast without and with IV contrast 1 See references [2,4-7]. O MRI breast without IV contrast 1 See references [2,4-7]. O FDG-PEM 1 See references [2,4-7]. ☢☢☢☢ Sestamibi MBI 1 See references [2,4-7]. ☢☢☢ Ductography 1 See references [2,4-7]. ☢☢ Image-guided core biopsy breast 1 See references [2,4-7]. Varies Image-guided fine needle aspiration breast 1 Varies *Relative Rating Scale: 1,2,3 Usually not appropriate; 4,5,6 May be appropriate; 7,8,9 Usually appropriate Radiation Level Variant 2: Pathologic nipple discharge. Male or female 40 years of age or older. Initial imaging examination. Radiologic Procedure Rating Comments RRL* See references [3,6,8,10,13,14,16,25- Mammography diagnostic 9 29,32,34,42-44,71-73]. ☢☢ See references [3,6,8,10,13,14,16,25- Digital breast tomosynthesis diagnostic 9 29,32,34,42-44,71-73]. ☢☢ US is usually complementary to mammography. It can be an alternative to mammography if the patient had a recent US breast 9 mammogram or is pregnant. See O references [3,5,10,12,13,16,25,30,31,45- 49]. MRI breast without and with IV contrast 1 See references [3,8,23,24,35,46,51-55]. -

Ductoscopy-Guided and Conventional Surgical Excision

Breast Cancer Ductoscopy-guided and Conventional Surgical Excision a report by Seema A Khan, MD Department of Surgery Feinberg School of Medicine and Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University DOI: 10.17925/OHR.2006.00.00.1i Radiologic imaging is routinely used to evaluate unhelpful. Galactography has been used to evaluate women with spontaneous nipple discharge (SND), but women with SND with variable success.6,7 When SND definitive diagnosis is usually only achieved by surgical is caused by peripheral intraductal lesions, terminal duct excision (TDE). Ductoscopy has been galactography provides localizing information and can reported to result in improved localization of also assess the likelihood of malignancy,4 although intraductal lesions and may avoid surgery in women definitive diagnosis requires central or terminal duct with endoscopically normal ducts. excision (TDE). Duct excision is also therapeutic unless malignancy is discovered.2,8 Mammary endoscopy Nipple discharge is responsible for approximately 5% of (ductoscopy) is a recently introduced technique that annual surgical referrals.1 Not all forms of spontaneous may allow more precise identification and delineation nipple discharge (SND) are associated with significant of intraductal disease but is not currently a standard pathologic findings. The clinical features of SND that practice among most surgeons. Ductoscopy has been are associated with a high likelihood of intraductal reported to result in improved localization of neoplasia include unilaterality, persistence, emanation intraductal lesions9–11 and may avoid surgery in women from a single duct, and watery, serous, or bloody with endoscopically normal ducts. However, appearance.2,3 Discharges with these characteristics are ductoscopy adds to time and expense in the operating classified as pathologic and have traditionally been room (OR), and the yield of significant pathologic considered an indication for surgical excision of the lesions reported in separate series of women who are involved duct. -

Mammary Ductoscopy, Aspiration and Lavage

Cigna Medical Coverage Policy Effective Date ............................ 2/15/2014 Subject Mammary Ductoscopy, Next Review Date ...................... 2/15/2015 Coverage Policy Number ................. 0057 Aspiration and Lavage Table of Contents Related Coverage Policies Coverage Policy .................................................. 1 Emerging Breast Biopsy/Localization General Background ........................................... 1 Procedures Coding/Billing Information ................................. 10 Electrical Impedance Scanning (EIS) and References ........................................................ 10 Optical Imaging of the Breast Genetic Testing for Susceptibility to Breast and Ovarian Cancer (e.g., BRCA1 & BRCA2) Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Breast Mammography Prophylactic Mastectomy INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE The following Coverage Policy applies to health benefit plans administered by Cigna companies. Coverage Policies are intended to provide guidance in interpreting certain standard Cigna benefit plans. Please note, the terms of a customer’s particular benefit plan document [Group Service Agreement, Evidence of Coverage, Certificate of Coverage, Summary Plan Description (SPD) or similar plan document] may differ significantly from the standard benefit plans upon which these Coverage Policies are based. For example, a customer’s benefit plan document may contain a specific exclusion related to a topic addressed in a Coverage Policy. In the event of a conflict, a customer’s benefit plan document always supersedes the information in the Coverage Policies. In the absence of a controlling federal or state coverage mandate, benefits are ultimately determined by the terms of the applicable benefit plan document. Coverage determinations in each specific instance require consideration of 1) the terms of the applicable benefit plan document in effect on the date of service; 2) any applicable laws/regulations; 3) any relevant collateral source materials including Coverage Policies and; 4) the specific facts of the particular situation. -

Mammary Ductoscopy in the Current Management of Breast Disease

Surg Endosc (2011) 25:1712–1722 DOI 10.1007/s00464-010-1465-4 REVIEWS Mammary ductoscopy in the current management of breast disease Sarah S. K. Tang • Dominique J. Twelves • Clare M. Isacke • Gerald P. H. Gui Received: 4 May 2010 / Accepted: 5 November 2010 / Published online: 18 December 2010 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 Abstract terms ‘‘ductoscopy’’, ‘‘duct endoscopy’’, ‘‘mammary’’, Background The majority of benign and malignant ‘‘breast,’’ and ‘‘intraductal’’ were used. lesions of the breast are thought to arise from the epithe- Results/conclusions Duct endoscopes have become lium of the terminal duct-lobular unit (TDLU). Although smaller in diameter with working channels and improved modern mammography, ultrasound, and MRI have optical definition. Currently, the role of MD is best defined improved diagnosis, a final pathological diagnosis cur- in the management of SND facilitating targeted surgical rently relies on percutaneous methods of sampling breast excision, potentially avoiding unnecessary surgery, and lesions. The advantage of mammary ductoscopy (MD) is limiting the extent of surgical resection for benign disease. that it is possible to gain direct access to the ductal system The role of MD in breast-cancer screening and breast via the nipple. Direct visualization of the duct epithelium conservation surgery has yet to be fully defined. Few allows the operator to precisely locate intraductal lesions, prospective randomized trials exist in the literature, and enabling accurate tissue sampling and providing guidance these would be crucial to validate current opinion, not only to the surgeon during excision. The intraductal approach in the benign setting but also in breast oncologic surgery. -

Athletics Communications the Big Ten Conference

2020 OHIO STATE BASEBALL ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS BASEBALL HISTORY CREDENTIAL REQUESTS Assoc. ADs of Comm. ................Jerry Emig, Dan Wallenberg First Year ...........................................................................1881 Ohio State reserves the right to deny media credentials Director ..............................................................Leann Parker All-Time Record ......................................2,625-1,716-39 (.604) to any individual who is not affiliated with an official, Associate Directors ...................Mike Basford, Kyle Kuhlman, National Championships............................................. 1 (1966) recognized news gathering organization. Please direct all .......................................................Gary Petit, Brett Rybak College World Series Appearances ......................................4 credential requests to Brett Rybak via e-mail to rybak.13@ Assistant Director .......................................Candace Johnson (1951-65-66-67) osu.edu. Interns ..............................Danajha Clemons, Erin Cummings College World Series Record ..................................9-7 (.563) Website ........................................... OhioStateBuckeyes.com NCAA Tournament Appearances ........................................ 22 CREDENTIAL PICKUP Main Office Phone ............................................ 614-292-6861 (1951-55-65-66-67-82-91-92-93-94-95-97-99-2001-02- ... Credentials will be held at Bill Davis Stadium at the Baseball Contact ................................................. -

Mammary Ductoscopy, Aspiration and Lavage

Medical Coverage Policy Effective Date ............................................. 1/15/2021 Next Review Date ....................................... 1/15/2022 Coverage Policy Number .................................. 0057 Mammary Ductoscopy, Aspiration and Lavage Table of Contents Related Coverage Resources Overview .............................................................. 1 Coverage Policy ................................................... 1 General Background ............................................ 2 Medicare Coverage Determinations .................. 10 Coding/Billing Information .................................. 10 References ........................................................ 10 INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE The following Coverage Policy applies to health benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Certain Cigna Companies and/or lines of business only provide utilization review services to clients and do not make coverage determinations. References to standard benefit plan language and coverage determinations do not apply to those clients. Coverage Policies are intended to provide guidance in interpreting certain standard benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Please note, the terms of a customer’s particular benefit plan document [Group Service Agreement, Evidence of Coverage, Certificate of Coverage, Summary Plan Description (SPD) or similar plan document] may differ significantly from the standard benefit plans upon which these Coverage Policies are based. For example, a customer’s benefit plan document may -

Football Programs

HOMECOMING 50c SATURDAY OCT. 31 t ~:. ,,...- - Cleaner, fresher, S-rooofu.er\ NORTHWESTERN w ·ir WrLBUR E S - OHIO STATE Job~•F ~ Woodruff NYPP, Editor Nat" ummel ___----- A~verti1in M Don Snal Adverti1~--itrculatio! M anaeer pencer Co., 2!1 epre!entarive anager The Presld New York 16 ::•~son Ave Ohio Stnle es\'s Page ' . ., orthwesl alls -- ~i\dcal p~~fil Officials--· __ 110 tale Hes - ·- 4 S, ' ~""w•orthwes,.rnle •;•~m<o,layers ------ .. G, 8 M•,~••< Brn Uo<,enU, -- - 0 •••••Ohio .,"•St P<o,enand al J-1 omewm;O,• - ---- 12 ' ' <8, "'· "10 ,,coo::::•••••Com~•• · ate--Norl c., ..... K . h,, r"- f·•~·.. - '" ·-s i--;i,s- - - " • ,-.. " •-. ; .... "· "· :U: The Ba;ens' Records ears -- --- 20, 2• ~rchin-g e~!~I~ Outlook- - =-·- ----- 22 Hi~•too State RostePrersonncl-·--- 2~ V ort~we~ .,stern"l;fersily u -ea.I --------- ----- --··--·-·· ---- 34, '"3:15 ars1ty osier -----·- ·- f~~~!~~:J~~~ilo;;-·--=- -_ ~--- ___ :_ - :~ Sw<mm;o, ::•=<meoO- --• -- • ··-· "6f. The Golf co:f;s°erds ····- - -- 64--77 _-::::.::-·--··--------=-- --------- 67 --- 6!171 E T T E S co .. 11., THE AMERICAN TOBACCO 3 ~~~~ COM~ANY THE PRESIDENT'S PAGE W . W . HAYES, Head Coach ESCO SARKKINEN, HARRY L. STROBEL, WILLIAM R. HESS, End Coach Defensive Line Coach Freshma n Coach DOYT L. PERRY, Ba ckfield Coach I the stands today are thou ands of alumni of Ohio State University. To them I want to extend an especial greeting on this traditional Homecoming occasion. Throughout the campus today and tonight there will be scenes of reunion. I want to join in wishing all alumni a pleasant return to their Alma Mater. -

Ductoscope Lights up Breast Cancer Diagnosis

April 15, 2007 • www.familypracticenews.com Women’s Health 31 Ductoscope Lights Up Breast Cancer Diagnosis BY MICHELE G. SULLIVAN Diagnostic and autofluorescence ducto- Mid-Atlantic Bureau scopies were performed before segment or duct excision or lumpectomy. The addi- O RLANDO — Light may soon take a tional time required for the ductoscopy place in the diagnostic and surgical arma- was minimal, ranging from 5 to 15 minutes, mentarium for breast cancer. and there were no associated complica- Researchers at the Technical University tions. There was no need for intravenous of Munich have developed and are cur- administration of any contrast agent be- rently evaluating the world’s first autoflu- cause the procedure uses only light. orescence ductoscope, which has the po- The paper notes that areas of suspicion tential to diagnose the earliest forms of reflected light values distinctly different intraductal breast cancer and guide surgi- from those of normal tissue. “The degree cal treatment. of blue-violet color appears to be propor- The instrument combines an autofluo- tional to the degree of alteration in this tis- rescence light source and camera already sue, just as it is in bronchoscopy,” Dr. Ja- approved in Europe for diagnostic bron- cobs said at the meeting sponsored by the choscopy with a 1.3-mm diameter ducto- Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. scope. Like autofluorescence bron- “The more light we see, the more dys- choscopy, it operates on the principle that plastic the tissue should be.” healthy and dysplastic tissues reflect different percentages of light, Dr. Volker R. Jacobs said at a meeting on laparoscopy and minimally invasive surgery. -

Breast Ductoscopy: Technical Development from a Diagnostic to an Interventional Procedure and Its Future Perspective

Original Article · Originalarbeit Onkologie 2007;30:545–549 Published online: September 28, 2007 DOI: 10.1159/000108283 Breast Ductoscopy: Technical Development from a Diagnostic to an Interventional Procedure and Its Future Perspective Volker R. Jacobsa Stefan Paepkea Ralf Ohlingerb Susanne Grunwaldb Marion Kiechle-Bahata a Frauenklinik der Technischen Universität München, b Frauenklinik, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-Universität, Greifswald, Germany Key Words Schlüsselwörter Ductoscopy: interventional, diagnostic, future technical Duktoskopie: interventionelle, diagnostische, zukünftige development · Breast endoscopy · Breast duct procedure, technische Entwicklung · Milchgangsendoskopie · diagnostic Milchgangsuntersuchung, diagnostische Summary Zusammenfassung Background: Endoscopy of the female breast, known as Hintergrund: Endoskopie der weiblichen Brust, bekannt als ductoscopy, is increasingly gaining acceptance as a diag- Duktoskopie, gewinnt zunehmende Akzeptanz als Diagnosti- nostic procedure worldwide. Recent technical development kum weltweit. Neue technische Weiterentwicklungen von of ductoscopes and micro-instruments is shifting research Duktoskopen sowie dazugehörigen Mikroinstrumenten rich- interest from diagnostic to interventional ductoscopy. We ten das Forschungsinteresse von der diagnostischen auf die describe novel technical aspects and the resulting possible interventionelle Duktoskopie, die zum gegenwärtigen Zeit- future perspective of ductoscopy. Methods: This study com- punkt noch experimentell ist. Wir beschreiben diese neuarti- -

Ochsneroutcomes

PUBLISHED 2 016 OCHSNEROUTCOMES Digestive Diseases Patient referrals, transfers and consults are critically important, and we want to make it easy for referring providers and their staff. To refer your patient for a clinic appointment, call our Clinic Concierge at 855.312.4190. Ochsner’s longstanding tradition of bringing physicians together to improve health outcomes continues today. Our goals are to work together with our referring providers to serve the needs of patients and to provide coordinated treatment through partnerships that put patients first. We have automated physician-to-physician patient care summaries for hospital encounters and enhanced the patient experience by giving patients the ability to schedule appointments online. Close coordination and collaboration begin with transparency and access to the data you need to make informed decisions when advising your patients about care options. OchsnerOutcomes, a compilation of clinical data, represents only part of our efforts to better define the quality of Ochsner’s care and to share that information with you. Trusted, independent organizations give the highest marks to Ochsner’s quality. Ochsner Medical Center was the only healthcare institution in Louisiana to receive Warner L. Thomas national rankings in six specialties from U.S. News & World Report for 2015–2016. President & Chief Executive Officer Additionally, CareChex® named Ochsner Medical Center, Ochsner Baptist, a Campus Ochsner Health System of Ochsner Medical Center and Ochsner Medical Center – West Bank Campus among the top 10% in the nation in 17 different specialties and, for the fourth year in a row, Ochsner was named #1 in the country for liver transplant. -

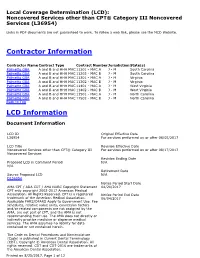

Local Coverage Determination for Noncovered Services Other Than

Local Coverage Determination (LCD): Noncovered Services other than CPT® Category III Noncovered Services (L36954) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information Contractor Name Contract Type Contract Number Jurisdiction State(s) Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11201 - MAC A J - M South Carolina Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11202 - MAC B J - M South Carolina Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11301 - MAC A J - M Virginia Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11302 - MAC B J - M Virginia Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11401 - MAC A J - M West Virginia Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11402 - MAC B J - M West Virginia Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11501 - MAC A J - M North Carolina Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11502 - MAC B J - M North Carolina Back to Top LCD Information Document Information LCD ID Original Effective Date L36954 For services performed on or after 06/05/2017 LCD Title Revision Effective Date Noncovered Services other than CPT® Category III For services performed on or after 08/17/2017 Noncovered Services Revision Ending Date Proposed LCD in Comment Period N/A N/A Retirement Date Source Proposed LCD N/A DL36954 Notice Period Start Date AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement 04/20/2017 CPT only copyright 2002-2017 American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved. CPT is a registered Notice Period End Date trademark of the American Medical Association.