Paleontology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Cranial Skeleton of Eosphargis Breineri NIELSEN

On the post-cranial skeleton of Eosphargis breineri NIELSEN. By EIGIL NIELSEN CONTENTS Preface 281 Introduction 282 Eosphargis breineri NIELSEN 283 Material and locality 283 Measurements 283 Skull 284 Vertebral column 284 Carapace 284 Plastron .291 Shoulder girdle 294 Fore-limb 296 Pelvis 303 Hind-limb 307 Remnants of soft tissues 308 Remarks on the relationship of Eosphargis 308 Literature 313 Plates 314 Preface. From the outstanding collector of fossils from the Lower Eocene marine mo clay deposits in Northern Jutland, Mr. M. BREINER JENSEN, leader of the Fur museum, I have received both in 1959 and 1960 for investiga- tion further remnants of turtles from the locality at Knudeklint on the island of Fur, where Mr. BREINEB. JENSEN in 1957 collected the almost complete skull of Eosphargis breineri NIELSEN described by me in 1959. I owe Mr. BREINER JENSEN a sincere thank for the permission to investigate also this new important material, the tedious preparation of which has been carried out in the laboratory of vertebrate paleontology in the Mineralogical and Geological Museum of the University of Copen- hagen mainly by stud. mag. BENTE SOLTAU, who also is responsible for the photographs in this paper. I hereby thank Mrs SOLTAU for her carefull work. Moreover I thank the artists Mrs BETTY ENGHOLM and Mrs RAGNA LARSEN who have drawn the text-figures, as well as stud. mag. SVEND 21 282 EIGIL NIELSEN : On the post-cranial skeleton of Eosphargis breineri NIELSEN E. B.-ALMGREEN, who in various ways has assisted in the finishing the illustrations. To the CARLSBERG FOUNDATION my thanks are due for financial support to the work of preparation and illustration of the material and to the RASK ØRSTED FOUNDATION for financial support to the reproduction of the illustrations. -

A New Microvertebrate Assemblage from the Mussentuchit

A new microvertebrate assemblage from the Mussentuchit Member, Cedar Mountain Formation: insights into the paleobiodiversity and paleobiogeography of early Late Cretaceous ecosystems in western North America Haviv M. Avrahami1,2,3, Terry A. Gates1, Andrew B. Heckert3, Peter J. Makovicky4 and Lindsay E. Zanno1,2 1 Department of Biological Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA 2 North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Raleigh, NC, USA 3 Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC, USA 4 Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, USA ABSTRACT The vertebrate fauna of the Late Cretaceous Mussentuchit Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation has been studied for nearly three decades, yet the fossil-rich unit continues to produce new information about life in western North America approximately 97 million years ago. Here we report on the composition of the Cliffs of Insanity (COI) microvertebrate locality, a newly sampled site containing perhaps one of the densest concentrations of microvertebrate fossils yet discovered in the Mussentuchit Member. The COI locality preserves osteichthyan, lissamphibian, testudinatan, mesoeucrocodylian, dinosaurian, metatherian, and trace fossil remains and is among the most taxonomically rich microvertebrate localities in the Mussentuchit Submitted 30 May 2018 fi fi Accepted 8 October 2018 Member. To better re ne taxonomic identi cations of isolated theropod dinosaur Published 16 November 2018 teeth, we used quantitative analyses of taxonomically comprehensive databases of Corresponding authors theropod tooth measurements, adding new data on theropod tooth morphodiversity in Haviv M. Avrahami, this poorly understood interval. We further provide the first descriptions of [email protected] tyrannosauroid premaxillary teeth and document the earliest North American record of Lindsay E. -

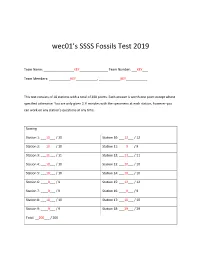

Wec01's SSSS Fossils Test 2019

wec01’s SSSS Fossils Test 2019 Team Name: _________________KEY________________ Team Number: ___KEY___ Team Members: ____________KEY____________, ____________KEY____________ This test consists of 18 stations with a total of 200 points. Each answer is worth one point except where specified otherwise. You are only given 2 ½ minutes with the specimens at each station, however you can work on any station’s questions at any time. Scoring Station 1: ___10___ / 10 Station 10: ___12___ / 12 Station 2: ___10___ / 10 Station 11: ____9___ / 9 Station 3: ___11___ / 11 Station 12: ___11___ / 11 Station 4: ___10___ / 10 Station 13: ___10___ / 10 Station 5: ___10___ / 10 Station 14: ___10___ / 10 Station 6: ____9___ / 9 Station 15: ___12___ / 12 Station 7: ____9___ / 9 Station 16: ____9___ / 9 Station 8: ___10___ / 10 Station 17: ___10___ / 10 Station 9: ____9___ / 9 Station 18: ___29___ / 29 Total: __200___ / 200 Team Number: _KEY_ Station 1: Dinosaurs (10 pt) 1. Identify the genus of specimen A Tyrannosaurus (1 pt) 2. Identify the genus of specimen B Stegosaurus (1 pt) 3. Identify the genus of specimen C Allosaurus (1 pt) 4. Which specimen(s) (A, B, or C) are A, C (1 pt) Saurischians? 5. Which two specimens (A, B, or C) lived at B, C (1 pt) the same time? 6. Identify the genus of specimen D Velociraptor (1 pt) 7. Identify the genus of specimen E Coelophysis (1 pt) 8. Which specimen (D or E) is commonly E (1 pt) found in Ghost Ranch, New Mexico? 9. Which specimen (A, B, C, D, or E) would D (1 pt) specimen F have been found on? 10. -

Abelisaurus Comahuensis 321 Acanthodiscus Sp. 60, 64

Index Page numbers in italic denote figure. Page numbers in bold denote tables. Abelisaurus comahuensis 321 structure 45-50 Acanthodiscus sp. 60, 64 Andean Fold and Thrust Belt 37-53 Acantholissonia gerthi 61 tectonic evolution 50-53 aeolian facies tectonic framework 39 Huitrin Formation 145, 151-152, 157 Andes, Neuqu6n 2, 3, 5, 6 Troncoso Member 163-164, 167, 168 morphostructural units 38 aeolian systems, flooded 168, 169, 170, 172, stratigraphy 40 174-182 tectonic evolution, 15-32, 37-39, 51 Aeolosaurus 318 interaction with Neuqu6n Basin 29-30 Aetostreon 200, 305 Andes, topography 37 Afropollis 76 Andesaurus delgadoi 318, 320 Agrio Fold and Thrust Belt 3, 16, 18, 29, 30 andesite 21, 23, 26, 42, 44 development 41 anoxia see dysoxia-anoxia stratigraphy 39-40, 40, 42 Aphrodina 199 structure 39, 42-44, 47 Aphrodina quintucoensis 302 uplift Late Cretaceous 43-44 Aptea notialis 75 Agrio Formation Araucariacites australis 74, 75, 76 ammonite biostratigraphy 58, 61, 63, 65, 66, Araucarioxylon 95,273-276 67 arc morphostructural units 38 bedding cycles 232, 234-247 Arenicolites 193, 196 calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy 68, 71, Argentiniceras noduliferum 62 72 biozone 58, 61 highstand systems tract 154 Asteriacites 90, 91,270 lithofacies 295,296, 297, 298-302 Asterosoma 86 92 marine facies 142-143, 144, 153 Auca Mahuida volcano 25, 30 organic facies 251-263 Aucasaurus garridoi 321 palaeoecology 310, 311,312 Auquilco evaporites 42 palaeoenvironment 309- 310, 311, Avil6 Member 141,253, 298 312-313 ammonites 66 palynomorph biostratigraphy 74, -

Vertebrate Remains Are Relatively Well Known in Late Jurassic Deposits of Western Cuba. the Fossil Specimens That Have Been Coll

Paleontología Mexicana, 3 (65): 24-39 (versión impresa), 4: 24-39 (versión electrónica) Catalogue of late jurassiC VerteBrate (pisCes, reptilian) speCiMens froM western CuBa Manuel Iturralde-Vinent ¹, *, Yasmani Ceballos Izquierdo ² A BSTRACT Vertebrate remains are relatively well known in Late Jurassic deposits of western Cuba. The fossil specimens that have been collected so far are dispersed in museum collections around the world and some have been lost throughout the years. A reas- sessment of the fossil material stored in some of these museums’ collections has generated new data about the fossil-bearing lo- calities and greatly increased the number of formally identified specimens. The identified bone elements and taxa suggest a high vertebrate diversity dominated by actinopterygians and reptiles, including: long-necked plesiosaurs, pliosaurs, metriorhynchid crocodilians, pleurodiran turtles, ichthyosaurs, pterosaurs, and sauropod dinosaurs. This assemblage is commonly associated with unidentified remains of terrestrial plants and rare microor- ganisms, as well as numerous marine invertebrates such as am- monites, belemnites, pelecypods, brachiopods, and ostracods. This fossil assemblage is particularly valuable because it includes the most complete marine reptile record of a chronostratigraphic interval, which is poor in vertebrate remains elsewhere. In this contribution, the current status of the available vertebrate fossil specimens from the Late Jurassic of western Cuba is provided, along with a brief description of the fossil materials. Key words: Late Jurassic, Oxfordian, dinosaur, marine reptiles, fish, western Cuba. I NTRODUCTION Since the early 20th century, different groups of collectors have discovered 1 Retired curator, Museo a relatively rich and diverse vertebrate assemblage in the Late Jurassic stra- Nacional de Historia Natural, ta of western Cuba, which has been only partially investigated (Brown and Havana, Cuba. -

4. Palaeontology

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2015 Palaeontology Klug, Christian ; Scheyer, Torsten M ; Cavin, Lionel Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-113739 Conference or Workshop Item Presentation Originally published at: Klug, Christian; Scheyer, Torsten M; Cavin, Lionel (2015). Palaeontology. In: Swiss Geoscience Meeting, Basel, 20 November 2015 - 21 November 2015. 136 4. Palaeontology Christian Klug, Torsten Scheyer, Lionel Cavin Schweizerische Paläontologische Gesellschaft, Kommission des Schweizerischen Paläontologischen Abhandlungen (KSPA) Symposium 4: Palaeontology TALKS: 4.1 Aguirre-Fernández G., Jost J.: Re-evaluation of the fossil cetaceans from Switzerland 4.2 Costeur L., Mennecart B., Schmutz S., Métais G.: Palaeomeryx (Mammalia, Artiodactyla) and the giraffes, data from the ear region 4.3 Foth C., Hedrick B.P., Ezcurra M.D.: Ontogenetic variation and heterochronic processes in the cranial evolution of early saurischians 4.4 Frey L., Rücklin M., Kindlimann R., Klug C.: Alpha diversity and palaeoecology of a Late Devonian Fossillagerstätte from Morocco and its exceptionally preserved fish fauna 4.5 Joyce W.G., Rabi M.: A Revised Global Biogeography of Turtles 4.6 Klug C., Frey L., Rücklin M.: A Famennian Fossillagerstätte in the eastern Anti-Atlas of Morocco: its fauna and taphonomy 4.7 Leder R.M.: Morphometric analysis of teeth of fossil and recent carcharhinid selachiens -

Geological Survey of Ohio

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF OHIO. VOL. I.—PART II. PALÆONTOLOGY. SECTION II. DESCRIPTIONS OF FOSSIL FISHES. BY J. S. NEWBERRY. Digital version copyrighted ©2012 by Don Chesnut. THE CLASSIFICATION AND GEOLOGICAL DISTRIBUTION OF OUR FOSSIL FISHES. So little is generally known in regard to American fossil fishes, that I have thought the notes which I now give upon some of them would be more interesting and intelligible if those into whose hands they will fall could have a more comprehensive view of this branch of palæontology than they afford. I shall therefore preface the descriptions which follow with a few words on the geological distribution of our Palæozoic fishes, and on the relations which they sustain to fossil forms found in other countries, and to living fishes. This seems the more necessary, as no summary of what is known of our fossil fishes has ever been given, and the literature of the subject is so scattered through scientific journals and the proceedings of learned societies, as to be practically inaccessible to most of those who will be readers of this report. I. THE ZOOLOGICAL RELATIONS OF OUR FOSSIL FISHES. To the common observer, the class of Fishes seems to be well defined and quite distin ct from all the other groups o f vertebrate animals; but the comparative anatomist finds in certain unusual and aberrant forms peculiarities of structure which link the Fishes to the Invertebrates below and Amphibians above, in such a way as to render it difficult, if not impossible, to draw the lines sharply between these great groups. -

Early Tetrapod Relationships Revisited

Biol. Rev. (2003), 78, pp. 251–345. f Cambridge Philosophical Society 251 DOI: 10.1017/S1464793102006103 Printed in the United Kingdom Early tetrapod relationships revisited MARCELLO RUTA1*, MICHAEL I. COATES1 and DONALD L. J. QUICKE2 1 The Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, The University of Chicago, 1027 East 57th Street, Chicago, IL 60637-1508, USA ([email protected]; [email protected]) 2 Department of Biology, Imperial College at Silwood Park, Ascot, Berkshire SL57PY, UK and Department of Entomology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW75BD, UK ([email protected]) (Received 29 November 2001; revised 28 August 2002; accepted 2 September 2002) ABSTRACT In an attempt to investigate differences between the most widely discussed hypotheses of early tetrapod relation- ships, we assembled a new data matrix including 90 taxa coded for 319 cranial and postcranial characters. We have incorporated, where possible, original observations of numerous taxa spread throughout the major tetrapod clades. A stem-based (total-group) definition of Tetrapoda is preferred over apomorphy- and node-based (crown-group) definitions. This definition is operational, since it is based on a formal character analysis. A PAUP* search using a recently implemented version of the parsimony ratchet method yields 64 shortest trees. Differ- ences between these trees concern: (1) the internal relationships of aı¨stopods, the three selected species of which form a trichotomy; (2) the internal relationships of embolomeres, with Archeria -

The Largest Tropical Peat Mires in Earth History

Geological Society of America Special Paper 370 2003 Desmoinesian coal beds of the Eastern Interior and surrounding basins: The largest tropical peat mires in Earth history Stephen F. Greb William M. Andrews Cortland F. Eble Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40506, USA William DiMichele Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., USA C. Blaine Cecil U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia, USA James C. Hower Center for Applied Energy Research, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA ABSTRACT The Colchester, Springfield, and Herrin Coals of the Eastern Interior Basin are some of the most extensive coal beds in North America, if not the world. The Colchester covers an area of more than 100,000 km^, the Springfield covers 73,500-81,000 km^, and the Herrin spans 73,900 km^. Each has correlatives in the Western Interior Basin, such that their entire regional extent varies from 116,000 km^to 200,000 km^. Correlatives in the Appalachian Basin may indicate an even more widespread area of Desmoinesian peatland development, although possibly sUghtly younger in age. The Colchester Coal is thin, but the Springfield and Herrin Coals reach thicknesses in excess of 3 m. High ash yields, dominance of vitrinite macerals, and abundant lycopsids suggest that these Desmoinesian coals were deposited in topogenous (groundwater fed) to solige- nous (mixed-water source) mires. The only modern mire complexes that are as wide- spread are northern-latitude raised-bog mires, but Desmoinesian -

Osseous Growth and Skeletochronology

Comparative Ontogenetic 2 and Phylogenetic Aspects of Chelonian Chondro- Osseous Growth and Skeletochronology Melissa L. Snover and Anders G.J. Rhodin CONTENTS 2.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 17 2.2 Skeletochronology in Turtles ................................................................................................ 18 2.2.1 Background ................................................................................................................ 18 2.2.1.1 Validating Annual Deposition of LAGs .......................................................20 2.2.1.2 Resorption of LAGs .....................................................................................20 2.2.1.3 Skeletochronology and Growth Lines on Scutes ......................................... 21 2.2.2 Application of Skeletochronology to Turtles ............................................................. 21 2.2.2.1 Freshwater Turtles ........................................................................................ 21 2.2.2.2 Terrestrial Turtles ......................................................................................... 21 2.2.2.3 Marine Turtles .............................................................................................. 21 2.3 Comparative Chondro-Osseous Development in Turtles......................................................22 2.3.1 Implications for Phylogeny ........................................................................................32 -

Mesozoic Marine Reptile Palaeobiogeography in Response to Drifting Plates

ÔØ ÅÒÙ×Ö ÔØ Mesozoic marine reptile palaeobiogeography in response to drifting plates N. Bardet, J. Falconnet, V. Fischer, A. Houssaye, S. Jouve, X. Pereda Suberbiola, A. P´erez-Garc´ıa, J.-C. Rage, P. Vincent PII: S1342-937X(14)00183-X DOI: doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2014.05.005 Reference: GR 1267 To appear in: Gondwana Research Received date: 19 November 2013 Revised date: 6 May 2014 Accepted date: 14 May 2014 Please cite this article as: Bardet, N., Falconnet, J., Fischer, V., Houssaye, A., Jouve, S., Pereda Suberbiola, X., P´erez-Garc´ıa, A., Rage, J.-C., Vincent, P., Mesozoic marine reptile palaeobiogeography in response to drifting plates, Gondwana Research (2014), doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2014.05.005 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Mesozoic marine reptile palaeobiogeography in response to drifting plates To Alfred Wegener (1880-1930) Bardet N.a*, Falconnet J. a, Fischer V.b, Houssaye A.c, Jouve S.d, Pereda Suberbiola X.e, Pérez-García A.f, Rage J.-C.a and Vincent P.a,g a Sorbonne Universités CR2P, CNRS-MNHN-UPMC, Département Histoire de la Terre, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 38, 57 rue Cuvier, -

Steneosaurus Brevior

The mystery of Mystriosaurus: Redescribing the poorly known Early Jurassic teleosauroid thalattosuchians Mystriosaurus laurillardi and Steneosaurus brevior SVEN SACHS, MICHELA M. JOHNSON, MARK T. YOUNG, and PASCAL ABEL Sachs, S., Johnson, M.M., Young, M.T., and Abel, P. 2019. The mystery of Mystriosaurus: Redescribing the poorly known Early Jurassic teleosauroid thalattosuchians Mystriosaurus laurillardi and Steneosaurus brevior. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 64 (3): 565–579. The genus Mystriosaurus, established by Kaup in 1834, was one of the first thalattosuchian genera to be named. The holotype, an incomplete skull from the lower Toarcian Posidonienschiefer Formation of Altdorf (Bavaria, southern Germany), is poorly known with a convoluted taxonomic history. For the past 60 years, Mystriosaurus has been consid- ered a subjective junior synonym of Steneosaurus. However, our reassessment of the Mystriosaurus laurillardi holotype demonstrates that it is a distinct and valid taxon. Moreover, we find the holotype of “Steneosaurus” brevior, an almost complete skull from the lower Toarcian Whitby Mudstone Formation of Whitby (Yorkshire, UK), to be a subjective ju- nior synonym of M. laurillardi. Mystriosaurus is diagnosed in having: a heavily and extensively ornamented skull; large and numerous neurovascular foramina on the premaxillae, maxillae and dentaries; anteriorly oriented external nares; and four teeth per premaxilla. Our phylogenetic analyses reveal M. laurillardi to be distantly related to Steneosaurus bollensis, supporting our contention that they are different taxa. Interestingly, our analyses hint that Mystriosaurus may be more closely related to the Chinese teleosauroid (previously known as Peipehsuchus) than any European form. Key words: Thalattosuchia, Teleosauroidea, Mystriosaurus, Jurassic, Toarcian Posidonienschiefer Formation, Whitby Mudstone Formation, Germany, UK.