FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Lithobates Catesbeianus Global Invasive Species Database (GISD) 2021. Species Profile Lithobates Catesbeianus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Emerging Infectious Diseases on Amphibians: a Review of Experimental Studies

diversity Review Effects of Emerging Infectious Diseases on Amphibians: A Review of Experimental Studies Andrew R. Blaustein 1,*, Jenny Urbina 2 ID , Paul W. Snyder 1, Emily Reynolds 2 ID , Trang Dang 1 ID , Jason T. Hoverman 3 ID , Barbara Han 4 ID , Deanna H. Olson 5 ID , Catherine Searle 6 ID and Natalie M. Hambalek 1 1 Department of Integrative Biology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA; [email protected] (P.W.S.); [email protected] (T.D.); [email protected] (N.M.H.) 2 Environmental Sciences Graduate Program, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA; [email protected] (J.U.); [email protected] (E.R.) 3 Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA; [email protected] 4 Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Millbrook, New York, NY 12545, USA; [email protected] 5 US Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA; [email protected] 6 Department of Biological Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence [email protected]; Tel.: +1-541-737-5356 Received: 25 May 2018; Accepted: 27 July 2018; Published: 4 August 2018 Abstract: Numerous factors are contributing to the loss of biodiversity. These include complex effects of multiple abiotic and biotic stressors that may drive population losses. These losses are especially illustrated by amphibians, whose populations are declining worldwide. The causes of amphibian population declines are multifaceted and context-dependent. One major factor affecting amphibian populations is emerging infectious disease. Several pathogens and their associated diseases are especially significant contributors to amphibian population declines. -

Species Assessment for Boreal Toad (Bufo Boreas Boreas)

SPECIES ASSESSMENT FOR BOREAL TOAD (BUFO BOREAS BOREAS ) IN WYOMING prepared by 1 2 MATT MCGEE AND DOUG KEINATH 1 Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, 1000 E. University Ave, Dept. 3381, Laramie, Wyoming 82071; 307-766-3023 2 Zoology Program Manager, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, 1000 E. University Ave, Dept. 3381, Laramie, Wyoming 82071; 307-766-3013; [email protected] drawing by Summers Scholl prepared for United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Wyoming State Office Cheyenne, Wyoming March 2004 McGee and Keinath – Bufo boreas boreas March 2004 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 3 NATURAL HISTORY ........................................................................................................................... 4 Morphological Description ...................................................................................................... 4 Taxonomy and Distribution ..................................................................................................... 5 Habitat Requirements............................................................................................................. 8 General ............................................................................................................................................8 Spring-Summer ...............................................................................................................................9 -

ENDANGERED SPECIES: Groups Petition FWS to List Amargosa Toad (02/28/2008)

ENDANGERED SPECIES: Groups petition FWS to list Amargosa toad (02/28/2008) April Reese, Land Letter Western reporter The Amargosa toad should be added to the federal endangered species list, according to a petition filed Tuesday with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service by environmental groups. In their petition, filed Feb. 26, the Center for Biological Diversity and Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility argue that urban development, water diversions and increased off- road vehicle use throughout the toad's range in Nevada's Oasis Valley have pushed the species toward extinction. According to the groups, the Amargosa toad is already restricted to a 10-mile stretch of the Amargosa River -- one of Nevada's last free- flowing rivers -- and adjacent desert uplands. "It only has a small amount of habitat," said Daniel Patterson, PEER's southwest director, who formerly worked for the Bureau of Land Management in Nevada as an ecologist. "It's got no where to go. There's really no room for error." FWS considered listing the toad in the 1990s after receiving a petition from environmental groups but decided the species did not warrant Males tend to be smaller, reaching 3 to 4 inches, while federal protection. At the time, FWS concluded females may reach 3.5 to 5 inches. Unlike most frogs and toads, the Amargosa toad is voiceless except for “release that the toad was more widespread than the calls” or chirps made by males when grasped below their petition suggested, although it also said more forelimbs by another toad or human. Photo courtesy of FWS. -

Catalogue of the Amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and Annotated Species List, Distribution, and Conservation 1,2César L

Mannophryne vulcano, Male carrying tadpoles. El Ávila (Parque Nacional Guairarepano), Distrito Federal. Photo: Jose Vieira. We want to dedicate this work to some outstanding individuals who encouraged us, directly or indirectly, and are no longer with us. They were colleagues and close friends, and their friendship will remain for years to come. César Molina Rodríguez (1960–2015) Erik Arrieta Márquez (1978–2008) Jose Ayarzagüena Sanz (1952–2011) Saúl Gutiérrez Eljuri (1960–2012) Juan Rivero (1923–2014) Luis Scott (1948–2011) Marco Natera Mumaw (1972–2010) Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [Special Section]: 1–198 (e180). Catalogue of the amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and annotated species list, distribution, and conservation 1,2César L. Barrio-Amorós, 3,4Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, and 5J. Celsa Señaris 1Fundación AndígenA, Apartado Postal 210, Mérida, VENEZUELA 2Current address: Doc Frog Expeditions, Uvita de Osa, COSTA RICA 3Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, Museo de Historia Natural La Salle, Apartado Postal 1930, Caracas 1010-A, VENEZUELA 4Current address: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Río Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS 90619–900, BRAZIL 5Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Altos de Pipe, apartado 20632, Caracas 1020, VENEZUELA Abstract.—Presented is an annotated checklist of the amphibians of Venezuela, current as of December 2018. The last comprehensive list (Barrio-Amorós 2009c) included a total of 333 species, while the current catalogue lists 387 species (370 anurans, 10 caecilians, and seven salamanders), including 28 species not yet described or properly identified. Fifty species and four genera are added to the previous list, 25 species are deleted, and 47 experienced nomenclatural changes. -

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organizations. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Lamoreux, J. F., McKnight, M. W., and R. Cabrera Hernandez (2015). Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. xxiv + 320pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1717-3 DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2015.SSC-OP.53.en Cover photographs: Totontepec landscape; new Plectrohyla species, Ixalotriton niger, Concepción Pápalo, Thorius minutissimus, Craugastor pozo (panels, left to right) Back cover photograph: Collecting in Chamula, Chiapas Photo credits: The cover photographs were taken by the authors under grant agreements with the two main project funders: NGS and CEPF. -

Digitization Strategic Plan

Creating a Digital Smithsonian DIGITIZATION STRATEGIC PLAN Fiscal Years 2010–2015 1002256_StratPlan.indd 2 5/26/10 8:25:45 AM INTRODUCTION 2 Extending Reach/Enhancing Meaning 3 What, Exactly, Is Digitization? 3 What Are We Digitizing? 4 Launching a New Era 5 Broaden Access 5 Preserve Collections 5 Support Education 5 Enrich Context 6 A Straightforward Approach 6 Assessing Cost and Timelines 7 From Pioneer to Leader 7 Virtual Access Ensures Relevance and Impact 8 Infinite Reach 8 creating a GOALS, OBJECTIVES, ACTION STEPS 10 Mission 10 Values 10 digital smithsonian STRATEGIC GOALS 11 Goal 1: Digital Assets 11 Goal 2: Digitization Program 12 Goal 3: Organizational Capacity 13 APPENDIX A: DIGITIZATION STRATEGIC PLAN COMMITTEE CHARTER 14 APPENDIX B: SMITHSONIAN DIGITIZATION STRATEGIC PLAN COMMITTEE 14 APPENDIX C: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 15 Photo Credits 15 APPENDIX D: DIGITIZATION STRATEGIC PLAN WORKING GROUP MEMBERS 16 1002256_StratPlan.indd 3 5/26/10 8:25:45 AM creating a digital smithsonian 1002256_StratPlan.indd 1 5/26/10 8:25:45 AM Introduction Picture a room with infinite capacity. It is absent cabinets or shelves, yet it holds tens of millions of objects and records — scientifically invaluable specimens, artifacts that connect us to our heritage, and research findings from some of the greatest minds in the world. Delving into its contents, a schoolgirl sitting in a North Creating a Digital Smithsonian is an ambitious five-year Dakota classroom can hear the voices of Jane Addams plan that lays out how we will accomplish digitization — the and Linus Pauling plead for peace in earlier times. A activity that will help us realize these benefits. -

For Review Only

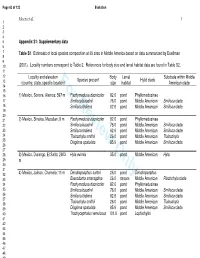

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

Dedicated to the Conservation and Biological Research of Costa Rican Amphibians”

“Dedicated to the Conservation and Biological Research of Costa Rican Amphibians” A male Crowned Tree Frog (Anotheca spinosa) peering out from a tree hole. 2 Text by: Brian Kubicki Photography by: Brian Kubicki Version: 3.1 (October 12th, 2009) Mailing Address: Apdo. 81-7200, Siquirres, Provincia de Limón, Costa Rica Telephone: (506)-8889-0655, (506)-8841-5327 Web: www.cramphibian.com Email: [email protected] Cover Photo: Mountain Glass Frog (Sachatamia ilex), Quebrada Monge, C.R.A.R.C. Reserve. 3 Costa Rica is internationally recognized as one of the most biologically diverse countries on the planet in total species numbers for many taxonomic groups of flora and fauna, one of those being amphibians. Costa Rica has 190 species of amphibians known from within its tiny 51,032 square kilometers territory. With 3.72 amphibian species per 1,000 sq. km. of national territory, Costa Rica is one of the richest countries in the world regarding amphibian diversity density. Amphibians are under constant threat by contamination, deforestation, climatic change, and disease. The majority of Costa Rica’s amphibians are surrounded by mystery in regards to their basic biology and roles in the ecology. Through intense research in the natural environment and in captivity many important aspects of their biology and conservation can become better known. The Costa Rican Amphibian Research Center (C.R.A.R.C.) was established in 2002, and is a privately owned and operated conservational and biological research center dedicated to studying, understanding, and conserving one of the most ecologically important animal groups of Neotropical humid forest ecosystems, that of the amphibians. -

Cyprinodon Nevadensis Mionectes Ash Meadows Amargosa Pupfish

Ash Meadows Amargosa pupfsh Cyprinodon nevadensis mionectes WAP 2012 species due to impacts from introduced detrimental aquatc species, habitat degradaton, and federal endangered status. Agency Status NV Natural Heritage G2T2S2 USFWS LE BLM-NV Sensitve State Prot Threatened Fish NAC 503.065.3 CCVI Presumed Stable TREND: Trend is stable to increasing with contnued on-going restoraton actvites. DISTRIBUTION: Springs and associated springbrooks, outlow stream systems and terminal marshes within Ash Meadows Natonal Wildlife Refuge, Nye Co., NV. GENERAL HABITAT AND LIFE HISTORY: This species is isolated to warm springs and outlows in Ash Meadows NWR including Point of Rocks, Crystal Springs, and the Carson Slough drainage. Pupfshes feed generally on substrate; feeding territories are ofen defended by pupfshes. Diet consists of mainly algae and detritus however, aquatc insects, crustaceans, snails and eggs are also consumed. Spawning actvity is typically from February to September and in some cases year round. Males defend territories vigorously during breeding season (Soltz and Naiman 1978). In warm springs, fsh may reach sexual maturity in 4-6 weeks. Reproducton variable: in springs, pupfsh breed throughout the year, may have 8-10 generatons/year; in streams, breeds in spring and summer, 2-3 generatons/year (Moyle 1976). In springs, males establish territories over sites suitable for ovipositon. Short generaton tme allows small populatons to be viable. Young adults typically comprise most of the biomass of a populaton. Compared to other C. nevadensis subspecies, this pupfsh has a short deep body and long head with typically low fn ray and scale counts (Soltz and Naiman 1978). CONSERVATION CHALLENGES: Being previously threatened by agricultural use of the area (loss and degradaton of habitat resultng from water diversion and pumping) and by impending residental development, the TNC purchased property, which later became the Ash Meadows NWR. -

Thermal Adaptation of Amphibians in Tropical Mountains

Thermal adaptation of amphibians in tropical mountains. Consequences of global warming Adaptaciones térmicas de anfibios en montañas tropicales: consecuencias del calentamiento global Adaptacions tèrmiques d'amfibis en muntanyes tropicals: conseqüències de l'escalfament global Pol Pintanel Costa ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) i a través del Dipòsit Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX ni al Dipòsit Digital de la UB. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX o al Dipòsit Digital de la UB (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) y a través del Repositorio Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. -

N.Orntates PUBLISHED by the AMERICAN MUSEUM of NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST at 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, N.Y

AMERICAN MUSEUM N.orntates PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, N.Y. 10024 Number 3068, 15 pp., 12 figures, 1 table June 11, 1993 A New Poison Frog from Manu INational Park, Southeastern Peru (Dendrobatidae, Epipedobates) LILY RODRIGUEZ' AND CHARLES W. MYERS2 ABSTRACT Epipedobates macero is a new species of den- ilar to a few other species occurring along the An- drobatid poison frog from lowland rain forest of dean front in eastern Peru, namely E. petersi and the Manu National Park, in the upper Madre de E. cainarachi, which differ in details ofcoloration, Dios drainage ofsoutheastern Peru. It is most sim- morphology, and vocalization. RESUMEN Epipedobates macero, especie nueva, es un den- del llano amaz6nico al pie de los Andes orientales drobatido venenoso de la selva pluvial baja del peruanos, a saber, E. petersi y E. cainarachi, las Parque Nacional del Manu, en el drenaje del Rio cuales difieren en detalles de coloracion, morfo- Alto Madre de Dios, al sudeste del Peru. Es similar logla, y vocalizacion. a otras dos especies que ocurren en los bosques ' Field Associate, Department of Herpetology and Ichthyology, American Museum of Natural History. Investi- gadora Asociada: Asociaci6n Peruana para la Conservaci6n de la Naturaleza (APECO), Parque Jos6 de Acosta 187, Lima 17, Perfi; and Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Mayor de San Marcos, apartado 140434, Lima 14, Peru. 2 Curator, Department of Herpetology and Ichthyology, American Museum of Natural History. Copyright © American Museum of Natural History 1993 ISSN 0003-0082 / Price $3.90 2 AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES NO. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations.