Historic Sites Commemorate 140Th Anniversary of Work Begins On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DCR and DENR/Study State Attractions Savings. (Public) Sponsors: Representative Howard (Primary Sponsor)

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2011 H 1 HOUSE BILL 944* Short Title: DCR and DENR/Study State Attractions Savings. (Public) Sponsors: Representative Howard (Primary Sponsor). For a complete list of Sponsors, see Bill Information on the NCGA Web Site. Referred to: Finance. May 17, 2012 1 A BILL TO BE ENTITLED 2 AN ACT TO REQUIRE THE DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL RESOURCES AND THE 3 DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES TO STUDY 4 VARIOUS REVENUE ENHANCEMENTS AND POTENTIAL SAVINGS AT STATE 5 HISTORIC SITES AND MUSEUMS, THE STATE ZOO, STATE PARKS, AND STATE 6 AQUARIUMS, AS RECOMMENDED BY THE JOINT LEGISLATIVE PROGRAM 7 EVALUATION OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE. 8 The General Assembly of North Carolina enacts: 9 SECTION 1. The Department of Cultural Resources shall implement the following 10 recommendations: 11 (1) Study site proximity and span of control to identify historic sites that could 12 adopt a coordinated management structure and report no later than 13 December 15, 2012, to the Senate Appropriations Committee on General 14 Government and Information Technology and the House Appropriations 15 Committee on General Government. 16 (2) Study reduced schedules for historic sites and report no later than December 17 15, 2012, to the Senate Appropriations Committee on General Government 18 and Information Technology and the House Appropriations Committee on 19 General Government. 20 (3) Study the feasibility of implementing more reliable mechanisms for counting 21 visitors and report no later than December 15, 2012, to the Senate 22 Appropriations Committee on General Government and Information 23 Technology and the House Appropriations Committee on General 24 Government. -

Bentonville Battlefield

Bentonville mech.05 4/8/05 3:56 PM Page 1 B e n t o n v i l l e B a t t l e f i e l d For more information, please contact: Bentonville Battlefield 5466 Harper House Road Four Oaks, North Carolina 27524 S cene of the (910) 594-0789 Fax (910) 594-0070 Tour stops at several battlefield locations give visitors a close-up L ast Maj o r look at where major actions took place. www.bentonvillebattlefield.nchistoricsites.org [email protected] Visitor Center tour stop: Begin your driving tour here. Confe d e r a t e • Bentonville Driving To u r O f fen s ive of the Confederate High Tide tour stop: View the portions of the battlefield where the Confederates had their greatest success Hours: on the first day of the battle. A p r. –Oct.: Mon.–Sat. 9 A.M.–5 P.M., Sun. 1–5 P.M. C i vil War • Confederate High Ti d e N o v. – M a r.: Tues.–Sat. 10 A.M.–4 P.M. • Union Artillery at the Morris Farm Sun. 1–4 P.M. M o rgan’s Stand tour stop: This is where some of the fiercest Call for holiday schedule. combat of the battle took place. • Fighting at the Cole Plantation: the “Battle of Acorn Run” Admission is free. • Fighting South of the Goldsboro Road: the “Bull Pen” • Confederate Line Crossing the Goldsboro Road Groups are requested to make advance reservations. N.C. Junior Reserve tour stop: Young boys aged 17 and 18 saw action against the Federals here. -

1 Office of Archives and History Report to North Carolina Historical

Office of Archives and History Report to North Carolina Historical Commission June 23, 2021 Budget highlights: Governor Cooper released his 2021-2021 budget recommendations March 24, 2021. Highlights for the Office of Archives and History included: • 2.5% raise and $1,000 bonus for state employees in both years of the biennium • $846,000 for America 250th preparations (non-recurring) Historical Resources: • QAR conservation and excavation $500,000 (recurring) • Highway Historical Markers $100,000 (recurring) • ANCHOR $165,000 in recurring funding (including two positions) and $28,000 non-recurring • Extend sunset of Article 3H Mill Tax Credit Museum of History: • Cash-Funded Capital Projects for Graveyard of the Atlantic renovation and exhibits ($4.2 million) and Maritime Museum ($1.5 million) • Bond-Funded Capital Projects for Museum of History ($54 million) State Historic Sites: • Maintenance funds, including $500,000 (recurring) and $500,000 (non-recurring) • Resilience funds, including $1 million (recurring) and $2.5 million (non-recurring) • African American History Curator • Bath High School Preservation (requires match from Town of Bath)-$280,000 non-recurring • Cash-Funded Capital Projects at Fort Fisher Historic Site Visitor Center ($8 million), State Capitol African American Monument ($2.5 million), Thomas Day House ($800,000), and Transportation Museum Power House ($2.25 million) • Bond-Funded Capitol Projects-$45 million for colonial and Revolutionary Era sites • Non-General Fund Capital Authorizations at Edenton, Charlotte Hawkins Brown Tea House, Transportation Museum Southern Railway, Bentonville Battlefield Harper House, Charlotte Hawkins Brown Galen Stone Cottage, Brunswick Town shoreline, and Bennett Place Visitor Center. American Rescue Plan: Governor Cooper released his proposed spending plan for the American Rescue Plan on May 19, 2021. -

GENERAL ASSEMBLY of NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2021 H 2 HOUSE BILL 332 Committee Substitute Favorable 4/21/21

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2021 H 2 HOUSE BILL 332 Committee Substitute Favorable 4/21/21 Short Title: Historic Sites-Property Sale Revenue. (Public) Sponsors: Referred to: March 22, 2021 1 A BILL TO BE ENTITLED 2 AN ACT TO ALLOW NET PROCEEDS FROM THE SALE OF CERTAIN REAL PROPERTY 3 OWNED BY OR UNDER THE CONTROL OF THE DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL AND 4 CULTURAL RESOURCES TO BE DEPOSITED INTO SPECIAL FUNDS TO BE USED 5 FOR THE BENEFIT OF CERTAIN STATE HISTORIC SITES AND MUSEUMS AND TO 6 REMOVE CERTAIN LAND FROM THE STATE NATURE AND HISTORIC 7 PRESERVE. 8 The General Assembly of North Carolina enacts: 9 SECTION 1. G.S. 146-30 reads as rewritten: 10 "§ 146-30. Application of net proceeds. 11 (a) The net proceeds of any disposition made in accordance with this Subchapter shall be 12 handled in accordance with the following priority: 13 (1) First, in accordance with the provisions of any trust or other instrument of title 14 whereby title to real property was acquired. 15 (2) Second, as provided by any other act of the General Assembly. 16 (3) Third, by depositing the net proceeds with the State Treasurer. 17 Nothing in this section, however, prohibits the disposition of any State lands by exchange for 18 other lands, but if the appraised value in fee simple of any property involved in the exchange is 19 at least twenty-five thousand dollars ($25,000), then the exchange shall not be made without 20 consultation with the Joint Legislative Commission on Governmental Operations. -

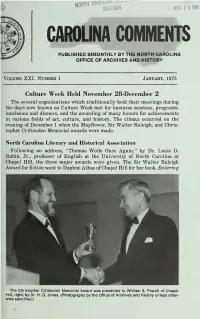

Carolina Comments

,-;-,.,;. CI\ROLINA 01;-,11.. .. - NORTH Ri\LE\GH APR 2 4 1980 CAROLINA COMMENTS PUBLISHED BIMONTHLY BY THE NORTH CAROLINA ~ , OFFICE OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY VOLUME XXI, NUMBER 1 JANUARY, 1973 Culture Week Held November 28-Decemher 2 The several organizations which traditionally hold their meetings during the days now known as Culture Week met for business sessions, programs, luncheons and dinners, and the awarding of many honors for achievements in various fields of art, culture, and history. The climax occurred on the evening of December 1 when the Mayflower, Sir Walter Raleigh, and Chris topher Crittenden Memorial awards were made. North Carolina Literary and Historical Association Following an address, "Thomas Wolfe Once Again," by Dr. Louis D. Rubin, Jr., professor of English at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the three major awards were given. The Sir Walter Raleigh Award for fiction went to Daphne Athas of Chapel Hill for her book, Entering The Christopher Crittenden Memorial Award was presented to William S. Powell of Chapel Hill, right, by Dr. H. G. Jones. (Photographs by the Office of Archives and History unless other wise specified.) The Sir Walter Raleigh Award was pre Mr. John F. Bivins, Jr., right, won the May sented by Mrs. John K. Brewer, left, on flower Cup for his book, The Moravian behalf of the Historical Book Club of North Potters in North Carolina. The presentation Carolina, Inc., to Miss Daphne Athas for was made by Mr. Samuel B. Dees, governor her book, Entering Ephesus. of the Mayflower Society in North Carolina. Ephesus; the presentation was made by Mrs. -

THE MIDDLETON PLACE PRIVY: a STUDY of DISCARD BEHAVIOR and the ARCHEOLOGICAL RECORD by Kenneth E

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Research Manuscript Series Institute of 8-1981 The iddM leton Place Privy: A Study of Discard Behavior and the Archeological Record Kenneth E. Lewis Helen W. Haskell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/archanth_books Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Kenneth E. and Haskell, Helen W., "The iddM leton Place Privy: A Study of Discard Behavior and the Archeological Record" (1981). Research Manuscript Series. 166. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/archanth_books/166 This Book is brought to you by the Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Institute of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Manuscript Series by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The iddM leton Place Privy: A Study of Discard Behavior and the Archeological Record Keywords Excavations, Ashley River, Middleton Place, Privies, Dorchester County, South Carolina, Archeology Disciplines Anthropology Publisher The outhS Carolina Institute of Archeology and Anthropology--University of South Carolina Comments In USC online Library catalog at: http://www.sc.edu/library/ This book is available at Scholar Commons: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/archanth_books/166 , THE MIDDLETON PLACE PRIVY: A STUDY OF DISCARD BEHAVIOR AND THE ARCHEOLOGICAL RECORD by Kenneth E. Lewis and Helen W. Haskell Research Man~seript Series No. 174 This project was sponsored by the Middleton Place Foundation with the assistance of a grant from the Coastal Plains Regional Commission. Prepared by the INSTITUTE OF ARCHEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY I UNIVERSITY OF SQUTH CAROLINA August 1981 The University of South Carolina offers equal opportunity in its employment, admissions, and educational activities, in accordance with Title I, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and other civil rights laws. -

North Carolina Listings in the National Register of Historic Places As of 9/30/2015 Alphabetical by County

North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov North Carolina Listings in the National Register of Historic Places as of 9/30/2015 Alphabetical by county. Listings with an http:// address have an online PDF of the nomination. Click address to view the PDF. Text is searchable in all PDFs insofar as possible with scans made from old photocopies. Multiple Property Documentation Form PDFs are now available at http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/MPDF-PDFs.pdf Date shown is date listed in the National Register. Alamance County Alamance Battleground State Historic Site (Alamance vicinity) 2/26/1970 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0001.pdf Alamance County Courthouse (Graham ) 5/10/1979 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0008.pdf Alamance Hotel (Burlington ) 5/31/1984 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0613.pdf Alamance Mill Village Historic District (Alamance ) 8/16/2007 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0537.pdf Allen House (Alamance vicinity) 2/26/1970 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0002.pdf Altamahaw Mill Office (Altamahaw ) 11/20/1984 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0486.pdf (former) Atlantic Bank and Trust Company Building (Burlington ) 5/31/1984 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0630.pdf Bellemont Mill Village Historic District (Bellemont ) 7/1/1987 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0040.pdf Beverly Hills Historic District (Burlington ) 8/5/2009 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0694.pdf Hiram Braxton House (Snow Camp vicinity) 11/22/1993 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0058.pdf Charles F. and Howard Cates Farm (Mebane vicinity) 9/24/2001 http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/AM0326.pdf -

The Eller Chronicles Official Publication of the Eller Family Association

VOL. IX-1 FEB 1995 THE ELLER CHRONICLES OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE ELLER FAMILY ASSOCIATION JOSHUA NUBO AND SUSAN MARIA ANDRESS ELLER Joshua4 Nubo ( Peterl, Daniell, Henry1 Eller, Sr.) (See Special Edition bound Separately) CONTENTS ANNOUNCING 4TH BIENNIAL ELLER FAMILY CONFERENCE i CONFERENCE REGISTRATION FORM (Modified from that in last issue) ii CONFERENCE SCHEDULE OF EVENTS (Tentative) 1-2 ANNOUNCEMENTS AND REQUESTS (from President Lynn Eller) 3-4 EDITORIAL COMMENTS (J.G. Eller) 4-6 QUERIES SECTION Moses W. and Nancy Roten Eller ( Lovetta Schweers) 7 Eller Baptist Ministers in N.C. (J. G. Eller) 7; 8-9 Rev. John F. Eller (answers to prev. query) 10; 13-14 "Squirrel" Eller (J. G. Eller) 10; 25-27 Faney Eller m John Clum 14 Elizabeth "Betty" Eller m Absalom "Abb" Wheeler 14 GENEALOGY SECTION Some Texas Eller Connections (Pat Wheeler Murray) 11 Elizabeth Stike Eller of Ashe Co., NC (Loveta Schweers) 13 Kurt Jeffrey Kilburn; Pedigree Chart (Des. Geo. M. Eller) 15 IN THE NEWS Hazel James and her daughter Carolyn Bell of Cleburne, TX 17 John and Lucy Eller of Skiatook, OK 18 Dr. Ronald D. Eller of the University ofKentucky 19-22 The Thomas Wolfe and Biltmore Houses, Asheville, NC 22-23 NECROLOGY Pat Vance Eller of Avery Co., NC 24 Louise Coolidge ofMcCook, Nebraska 24 Dr. Frank W. Eller ofWilkes Co., NC 24 "Squirrel" Eller of Roanoke, VA 10; 25-27 James Eller, New Kinsington, PA 29 EFA FISCAL REPORTS Auditor's Report for year ending 1993 (Roger F. Eller) 28 1994 Final Financial Report (Nancy Eller) 29 1995 Proposed Budget (Nancy Eller) 30 MAPS Asheville and Western North Carolina 31-32 BACK COVER Front View: Radisson Hotel, Asheville, NC 33 Night View : Radisson Hotel, Asheville, NC Descendants of Joshua Nubo Eller (Submitted by Alfred D. -

Buncombe County

Sites in the Blue Ridge National Heritage Area Listed on the National Register of Historic Places As of April 21, 2006 ALLEGHANY COUNTY Alleghany County Courthouse (Sparta) 5/10/1979 Brinegar Cabin (Whitehead vicinity) 1/20/1972 Elbert Crouse Farmstead (Low Notch 7/29/1982 Robert L. Doughton House (Laurel Springs) 8/13/1979 J.C. Gambill Site (Archaeology) (New Haven 4/3/1978 Bays Hash Site (Archaeology) (Amelia vicinity) 4/19/1978 Jarvis House (Sparta vicinity) 10/16/1991 Rock House (Roaring Gap) 8/11/2004 William Weaver House (Peden vicinity) 11/7/1976 ASHE COUNTY Shubal V. Alexander District (Archaeology) (Crumpler vicinity) 9/1/1978 Ashe County Courthouse (Jefferson) 5/10/1979 Baptist Chapel Church and Cemetery (Helton vicinity) 11/13/1976 Bower-Cox House (Nathans Creek) 11/7/1976 Brinegar District (Archaeology) (Crumpler) 3/12/1978 A.S. Cooper Farm (Brownwood vic.) 9/24/2001 Samuel Cox House MOVED (Scottville vicinity) 11/7/1976 Elkland School Gymnasium (Todd vic.) 6/22/2004 Glendale Springs Inn (Glendale Springs) 10/10/1979 Grassy Creek Historic District (Grassy Creek) 12/12/1976 R. T. Greer and Company Herb and Root Warehouse (Brownwood/Fleet 4/18/2003 Miller Homestead (Lansing vicinity) 9/24/2001 John M. Pierce House (Weaver's Ford 11/7/1976 Poe Fish Weir Site (Archaeology) (Nathan's Creek) 5/22/1978 Thompson's Bromine and Arsenic Springs (Crumpler vicinity) 10/22/1976 Todd Rural Historic District (Todd) 1/28/2000 John W. Tucker House (Lansing vicinity) 7/29/1985 William Waddell House (Sussex vicinity) 11/7/1976 AVERY COUNTY Avery County Courthouse (Newland) 5/10/1979 Former Avery County Jail (Newland) 12/9/1999 Banner Elk Hotel (Banner Elk) 10/6/2000 Page 1 of 13 Crossnore Presbyterian Church (Crossnore) 3/1/1996 Elk Park Elementary School (Elk Park) 12/16/2005 Linville Historic District (Linville) 3/7/1979 Weaving Room at Crossnore (Crossnore) 4/25/2001 Ray Wiseman House (Altamont) 11/29/1996 BUNCOMBE COUNTY Judge Junius Adams House (Biltmore Forest) 10/5/2001 Alexander Inn (Swannanoa 5/31/1984 Mrs. -

THE NORTH CAROLINA OFFICE of ARCHIVES and HISTORY 2012-2014 BIENNIAL REPORT OFFICE of ARCHIVES and HISTORY July 1, 2012–June 30, 2014

FIFTY-FIFTH BIENNIAL REPORT THE NORTH CAROLINA OFFICE OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY 2012-2014 BIENNIAL REPORT OFFICE OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY July 1, 2012–June 30, 2014 FIFTY-FIFTH BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE NORTH CAROLINA OFFICE OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY July 1, 2012 through June 30, 2014 Raleigh Office of Archives and History North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources 2015 © 2015 by the North Carolina Office of Archives and History All rights reserved NORTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL RESOURCES SUSAN W. KLUTTZ Secretary OFFICE OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY KEVIN CHERRY Deputy Secretary DIVISION OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES RAMONA BARTOS Director DIVISION OF ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SARAH KOONTS Director DIVISION OF STATE HISTORIC SITES KEITH P. HARDISON Director DIVISION OF STATE HISTORY MUSEUMS KENNETH B. HOWARD Director NORTH CAROLINA HISTORICAL COMMISSION MILLIE M. BARBEE (2015) Chair Mary Lynn Bryan (2017) Valerie A. Johnson (2015) David C. Dennard (2015) Margaret Kluttz (2019) Samuel B. Dixon (2019) B. Perry Morrison Jr. (2017) Chris E. Fonvielle Jr. (2019) Richard Starnes (2017) William W. Ivey (2019) Harry L. Watson (2017) EMERITI: Kemp P. Burpeau, N. J. Crawford, H. G. Jones, William S. Powell, Alan D. Watson, Max R. Williams CONTENTS DeputySecretary’sReport............................1 Roanoke Island Festival Park .......................13 TryonPalace................................ 16 NorthCarolinaTransportationMuseum.................28 DivisionofHistoricalResources........................34 Education and Outreach Branch......................34 -

Historic Sites Alamance Battleground Physical: • No Designated Paved

Historic Sites Alamance Battleground Physical: • No designated paved parking spaces. Accommodations can be made as necessary for easy access. • Natural ground with grass. No paved paths. Some slopes. Benches near the restroom provide an area of rest. • The visitor center entrance is level. • One accessible restroom for each gender. • Visitors may drive or be driven to the Allen House (approx. 80 yards from the visitor center). Staff are available to assist visitors with mobility issues. Hearing: • Orientation video has volume control but is not captioned. Vision: • Restroom signs have Braille. • Two plaques outside the visitor center are a map of the site with raised letters and shapes that visitors with vision loss can feel. • Two monuments across the street also have raised letters. Aycock Birthplace Physical: • Two marked accessible parking spaces: one at the visitor center and one at the picnic shelter. • A concrete path at least 4 feet wide with slopes leads from the parking lot to the visitor center. An uneven dirt path leads to the schoolhouse and the home. • The interior of the visitor center has a ramp and carpeted floors. • The entrance to the visitor center has a ramp. Other buildings have steps. • One accessible restroom for each gender. Hearing: • A video tour is available, but is not captioned. Vision: • 12 Braille copies of the site’s brochure are available (courtesy of the Governor Morehead School for the Blind). • The site offers tactile tours that allow visitors to touch reproduction items. • Restroom signs have Braille. Battleship North Carolina Physical: • Marked accessible parking spaces are available. • The entrance has a ramp. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory·· Nomination Form !Date Entered

I form No. 10-300 \0-1A\ ~\\e'-~· UNITED STATicS DEPARTMENT 01- THE INTERIOR FOR NP$ USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVEO INVENTORY-- NOMINATION FORM SEE INST~UCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES-- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS DNAME HISTORIC Downtown Asheville Historic District AND/OR COMMON IBLOCATION STREET & NUMBER Thirty blocks of the central business district _NOT FOR PUBLICA liON CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAl. DISTRICT Asheville VICINITY OF 11th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Nqrth cargljpa 37 Buncombe 02] DcLAsSIFICAnoN CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X..OISTRICT -PUBLIC ~OCCUPIED -AGRICULTURE __ MUSEUM _BUJLOING(S) -PRIVATE KuNoccurJeo lLCOMMERCIAL _PARK -STRUCTURE X_BQTH X WORK IN PROGRESS lLEDUCATIONAL lLPRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE x_ENTERTAINMENT lLRELIGIOUS -OBJECT _IN PROCESS ~YES: RESTRICTED lLGOVERNMENT lLSCIENTIFIC -BEING CONSIDERED K YES: UNRESTRICTED _INDUSTRIAl _TRANSPORTATION ~NO -MILITARY lLOTHER: City DowNER oF PROPERTY NAME Multiple Ownership STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF IJLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY Of DEEDS;ETC. Buncombe County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Asheville North Carolina ~\~REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Historic Architectural Resources of Downtown Asheville conducted by staff of the Archeology & Historic Preservation Section, N, C. Division of DATE Arch1ves and H1story 1977-1978 -FEDERAL llSTATE _COUNTY _LOCAL --~~~~~~--------~~--~~--~--~~~--- OEPOSITORYFOR survey and Planning Branch, Archeology and Historic SURVEY RECORDS --=:-:-::=:::--~--"'xeserva t jon Section CITY, TOWN STATE Raleigh North Carolina B DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCEllENT _OETERIORA TED -UNALTERED lLORIGINAL SITE JLGOOD _RUINS XALTEREO _MOVED DATE ____ _fAIR _ UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND OHIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The downtown Asheville district is composed of the core of the central business district and associated governmental and institutional areas.