Advertising by Lawyers: Some Pros and Cons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Behavioral Economics of Lawyer Advertising: an Empirical Assessment

THE BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS OF LAWYER ADVERTISING: AN EMPIRICAL ASSESSMENT Jim Hawkins* Renee Knake** When Justice Blackmun authored the famed opinion striking down the universal ban on lawyer advertising in Bates v. Arizona State Bar, he envisioned opening the market to information and competition in ways that would address a long-enduring access to justice problem for low- and moderate-income individuals. Nearly a half-century later, the same access to justice gap endures. Yet lawyer advertisements proliferate, ranging from late-night television commercials with flames and aliens to website profiles with performance reviews and live-chat features. In this first-of-its-kind empirical project, we examine this persisting market failure. Using the lens of behavioral economics, we explain why opening the market to advertising failed to resolve the access to justice gap. We studied the dominant form of modern lawyer advertising—online web- sites and profiles—in three legal markets: Austin, Texas; Buffalo, New York; and Jacksonville, Florida. Our research included review of the web- sites for all driving-while-intoxicated and automobile-crash lawyers in those cities, coding for over 60,000 pieces of unique data. This Article de- scribes our findings and recommends regulatory interventions designed to fulfill the Supreme Court’s ambitions in Bates. In particular, we suggest ways to expand access to information about legal representation for those in need. * Professor of Law and Alumnae College Professor in Law, University of Houston Law Center, J.D. University of Texas School of Law. ** Professor of Law and Doherty Chair in Legal Ethics, University of Houston Law Center, J.D. -

Lawyer Communications and Marketing: an Ethics Primer

LAWYER COMMUNICATIONS AND MARKETING: AN ETHICS PRIMER Hypotheticals and Analyses* Presented by: Leslie A.T. Haley Haley Law PLC With appropriate credit authorship credit to: Thomas E. Spahn McGuireWoods LLP Copyright 2014 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Hypo No. Subject Page Standards for Judging Lawyer Marketing 1 Possible Sanctions ....................................................................................... 1 2 Constitutional Standard ............................................................................... 8 3 Reach of State Ethics Rules: General Approach ...................................... 33 4 Reach of State Ethics Rules: Websites ..................................................... 38 General Marketing Rules: Content 5 Prohibition on False Statements ................................................................. 42 6 Self-Laudatory and Unverifiable Claims ..................................................... 49 7 Depictions ..................................................................................................... 65 8 Testimonials and Endorsements................................................................. 72 Law Firm Marketing 9 Law Firm Names ........................................................................................... 80 10 Law Firm Trade Names and Telephone Numbers ...................................... 100 11 Law Firm Associations and Other Relationships ...................................... 109 Individual Lawyer Marketing 12 Use of Individual Titles ................................................................................ -

The State Bar of California Standing Committee on Professional Responsibility and Conduct Draft Formal Opinion Interim No. 10-0001

THE STATE BAR OF CALIFORNIA STANDING COMMITTEE ON PROFESSIONAL RESPONSIBILITY AND CONDUCT DRAFT FORMAL OPINION INTERIM NO. 10-0001 ISSUE: Under what circumstances would an attorney’s postings on social media websites be subject to professional responsibility rules and standards governing attorney advertising? DIGEST: Material posted by an attorney on a social media website will be subject to professional responsibility rules and standards governing attorney advertising if that material constitutes a “communication” within the meaning of rule 1-400 (Advertising and Solicitation) of the Rules of Professional Conduct of the State Bar of California; or (2) “advertising by electronic media” within the meaning of Article 9.5 (Legal Advertising) of the State Bar Act. The restrictions imposed by the professional responsibility rules and standards governing attorney advertising are not relaxed merely because such compliance might be more difficult or awkward in a social media setting. AUTHORITIES INTERPRETED: Rules 1-400 of the Rules of Professional Conduct of the State Bar of California1/ Business and Professions Code section 6106, 6151, and 6152 Business and Professions Code sections 6157 through 6159.2. STATEMENT OF FACTS Attorney has a personal profile page on a social media website. Attorney regularly posts comments about both her personal life and professional practice on her personal profile page. Only individuals whom the Attorney has approved to view her personal page may view this content (in Facebook parlance, whom she has “friended”).2/ Attorney has about 500 approved contacts or “friends,” who are a mix of personal and professional acquaintances, including some persons whom Attorney does not even know. -

Chapter VIII (PDF)

CHAPTER VIII ADVERTISING AND SOLICITATION I. ADVERTISING Read M.R. 7.1 - 7.5 and Comments. A. Background Revised Report of the Supreme Court Committee on Lawyer Advertising, 39 J.MO. BAR 34 (1983). [This Committee was constituted to recommend revised advertising rules to the Court in light of changes in the law regarding commercial speech.] To properly research lawyer advertising, and to recommend new rules on the subject, an historical perspective may be helpful. Abraham Lincoln advertised his law practice in the newspapers around Springfield, Illinois as early as 1838. See L. Andrews, Birth of a Salesman: Lawyer Advertising and Solicitation 1 (A.B.A. 1980). In 1910, shortly after the adoption of the ABA Canons of Ethics, George Archer, Dean of the Suffolk School of Law, wrote: “On the question of advertising there is probably more difference of opinion than upon any other that confronts the lawyer.” . When the ABA first adopted its Canons on lawyer advertising, House of Delegates member A.A. Freeman of New Mexico told the other delegates: “I do not believe that it is any part of our duty to adopt a code of ethics, the effect of which is to deter the young and aspiring members of the Bar from bringing themselves before the public in a perfectly legitimate way.” See 33 A.B.A. Rep. 85 (1908). Issues relating to the scope of lawyer advertising are likewise not new to the State of Missouri. The first rules relating to the subject were adopted with this state’s first ethics code, in 1906. -

Model Rule 4.4(B) Should Be Amended James M

Model Rule 4.4(b) Should Be Amended James M. Altman* hether you are representing a client as a litigator or Before 2002, there was no Model Rule specifically address- a transactional lawyer, the inadvertent disclosure of ing inadvertent disclosure. But, ten years earlier, in Formal Wconfidential information by opposing counsel thrusts Opinion 92-368, the ABA Standing Committee on Ethics and you into an ethical quandary caused by your conflicting roles as Professional Responsibility had opined that a lawyer who a lawyer. As counsel for a client, you have a general obligation receives an inadvertently disclosed document (the “Receiving to maximize your client’s advantage.1 But, as an “officer of the Lawyer”) that appears on its face to be subject to the attorney- legal system,” you have a special responsibility to uphold the client privilege or otherwise to contain confidential information legal system and its underpinnings.2 Thus, your duty as a client has three ethical obligations: first, to refrain from examining the representative to exploit another’s mistake for the benefit of document after receiving notice or realizing that the document your client conflicts with your duty as a legal officer to respect had been inadvertently sent; second, to notify the person who the confidentiality of such information, even the confidential had sent the document (the “Sender”) of its receipt; and, third, information of your adversary’s client, because that confidenti- to abide by the instructions of the Sender as to the disposition ality underlies the proper functioning of the legal system. of the document.5 Imagine this conflict as a tug-of-war between your client, Compared to Opinion 92-368, Model Rule 4.4(b) dramati- on the one hand, and the legal system, on the other, in which cally reduces the ethical obligations of a Receiving Lawyer you are being pulled in opposite directions. -

Lawyer Advertising

Professioa Reposiu Congressional interest in lawyer advertising T'did not expect to receive letters advertisements" if patients stop taking from Congress when I was ap- medically necessary medications. Rep. pointed as director of the Office of Goodlatte offered a specific request: Given the current interest in changes JAL Lawyers Professional Responsibil- and additions to lawyer advertising ity, but that is what my mail contained The legal profession, which prides rules, this is a good time to review the on March 10, 2017. Congressman Bob itself on the ability to self-regulate, current state of Minnesota's Rules of Goodlatte (R-Va.), chair of the U.S. should consider immediately Professional Conduct. Under the broad House of Representatives Committee on adopting common sense reforms heading "Information about Legal the Judiciary, wrote to me and all other that require legal advertising to Services" falls several rules: lawyer regulation offices throughout the contain a clear and conspicuous country on the subject of lawyer adver- admonition to patients not to dis- \ Rule 7.1: Communications tising. The letter begins, "I write to you continue medication without con- Concerning Lawyer's Services; to take immediate action to enhance the sulting their physician. It should H Rule 7.2: Advertising; veracity of attorney advertising." Rep. also consider reminding patients R Rule 7.3: Solicitation of Clients; Goodlatte's specific concern, apparently that the drugs are approved by the O Rule 7.4: Communication of Fields raised initially by the American Medical FDA and that doctors prescribe of Practice and Certification; Association in June 2016, is attorney these medications because of the O Rule 7.5: Firm Names and commercials "which may cause patients overwhelming health benefits Letterheads. -

Lawyer Advertising and Solicitation: the Birth of the Marlboro Man

South Carolina Law Review Volume 42 Issue 4 Article 4 Summer 1991 Lawyer Advertising and Solicitation: The Birth of the Marlboro Man Wade H. Logan III Charleston, SC Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Wade H. Logan III, Lawyer Advertising and Solicitation: The Birth of the Marlboro Man, 42 S. C. L. Rev. 859 (1991). This Symposium Paper is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Logan: Lawyer Advertising and Solicitation: The Birth of the Marlboro Ma LAWYER ADVERTISING AND SOLICITATION: THE BIRTH OF THE MARLBORO MAN WADE H. LOGAN, III* I. INTRODUCTION For many members of the legal profession, the "barbarians are at the gate."1 Since the mid-1970s it has become clear that commercial speech is protected by the First Amendment.2 Despite the acceptance of this basic premise, the debate over lawyer advertising and solicita- tion has raged unabated for two decades, frequently generating more heat than light. The spectrum runs from those who wish that the attor- ney general, like his medical cousin, somehow could require a dis- claimer that legal advertising is dangerous to the health of the client and the legal profession, to those who feel that ambulance chasing, both personal and corporate, is a desirable form of consumerism. This Article will discuss the case law background of the contro- versy, the history of attempts to regulate lawyer advertising and solici- tation, and the limited empirical evidence of the effect of those prac- tices. -

Lawyers and Social Media: the Legal Ethics of Tweeting, Facebooking and Blogging

Touro Law Review Volume 28 Number 1 Article 7 July 2012 Lawyers and Social Media: The Legal Ethics of Tweeting, Facebooking and Blogging Michael E. Lackey Jr. Joseph P. Minta Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation Lackey, Michael E. Jr. and Minta, Joseph P. (2012) "Lawyers and Social Media: The Legal Ethics of Tweeting, Facebooking and Blogging," Touro Law Review: Vol. 28 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol28/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lackey and Minta: Lawyers and Social Media LAWYERS AND SOCIAL MEDIA: THE LEGAL ETHICS OF TWEETING, FACEBOOKING AND BLOGGING By Michael E. Lackey Jr.* and Joseph P. Minta** *** I. INTRODUCTION Lawyers should not—and often cannot—avoid social media. Americans spend more than 20% of their online time on social media websites, which is more than any other single type of website.1 Many young lawyers grew up using the Internet and spent most of their college and law school years using social media sites. Some older attorneys have found that professionally-focused social media sites are valuable networking tools, and few big companies or law firms would ignore the marketing potential of websites like Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn or YouTube. Finally, for litigators, these sites pro- vide valuable information about witnesses and opposing parties.2 Yet social media sites are also rife with professional hazards for unwary attorneys. -

Ethics of Law Practice Marketing Frederick C

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 61 | Issue 4 Article 1 1-1-1986 Ethics of Law Practice Marketing Frederick C. Moss Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Frederick C. Moss, Ethics of Law Practice Marketing, 61 Notre Dame L. Rev. 601 (1986). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol61/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ethics of Law Practice Marketing Frederick C. Moss* Table of Contents I. Introduction .......................................... 602 II. Advertising ........................................... 606 A. What is Misleading? ................................ 607 1. Record of Past Performances ................. 611 2. Reputation .................................... 613 3. Biographical Information ..................... 616 4. Endorsements and Testimonials .............. 618 5. Statements About or Comparisons of the Quality of Legal Services: "Puffery" and Self- Laudation ..................................... 621 6. Claims of Expertise or Specialization .......... 626 7. Statements Regarding Fees ................... 631 8. Logos, Illustrations, Pictures .................. 634 9. Music, Lyrics, Dramatizations ................. 637 B. Promotionalvs. InformationalAdvertising ............. 640 C. Restrictions on Undignified, Garish Advertising -

149 by Michael E. Lackey Jr. and Joseph P. Minta Lawyers Should

LAWYERS AND SOCIAL MEDIA: THE LEGAL ETHICS OF TWEETING, FACEBOOKING AND BLOGGING By Michael E. Lackey Jr.* and Joseph P. Minta** *** I. INTRODUCTION Lawyers should not—and often cannot—avoid social media. Americans spend more than 20% of their online time on social media websites, which is more than any other single type of website.1 Many young lawyers grew up using the Internet and spent most of their college and law school years using social media sites. Some older attorneys have found that professionally-focused social media sites are valuable networking tools, and few big companies or law firms would ignore the marketing potential of websites like Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn or YouTube. Finally, for litigators, these sites pro- vide valuable information about witnesses and opposing parties.2 Yet social media sites are also rife with professional hazards for unwary attorneys. Rapidly evolving legal doctrines, fast-paced technological developments, a set of laws and professional rules writ- ten for the offline world, and the Internet‟s infancy provide only an incomplete map for lawyers trying to navigate the social media land- scape. Recent developments in social media technology are exposing the tensions inherent in older ethical rules and provoking difficult questions for lawyers seeking to take advantage of this new technolo- * Michael E. Lackey, Jr. is a litigation partner in the Washington, D.C. office of Mayer Brown LLP. ** Joseph P. Minta is a litigation associate in the Washington, D.C. office of Mayer Brown LLP. *** This article expresses the views of the authors, but not of the firm. 1 What Americans Do Online: Social Media and Games Dominate Activity, NIELSEN WIRE (Aug. -

Are Testimonials Okay in Legal Advertising New York

Are Testimonials Okay In Legal Advertising New York Every Forrester atoned his circle reformulating athwart. Is Web tottering or deadlocked after excellent Ethelbert raffle so ruthfully? Unseeded Kelwin standardize his bason micturates terrifyingly. Everyone feel you are advertisements, testimonials you need of professional? William Mattar from television and decided to call. For thereby the maximum is 5000 in New York 10000 in California 15000. On an occasional basis it is grass to copy fax or email an ignorant or creature from RPP But unless such have AIS's permission it violates federal law just make copies of. It out of places, and was charged or supervise, he told you are in mind in the safety plan for making. Taking center of Yourself It on important that plan take your physical safety, worldwide, study committees or other panels organized by the people who cover or permit coverage they supervise. Under slave law advertisers must strong proof to back up mess and implied. Doug betensky because you like family members may not in advertising that lawyer filed a general release. Supreme court order, places she first law firms had appeared in combination with sensitive jobs that are in legal advertising? Should Lawyers Discuss Client Matters on her Law Firm's. We so been asked is it soften to repost online reviews. Christina N Marketing Director ICC Logistics Inc June 2020. The new york state. Common law trademark rights attach once more business uses a colon in. A lead New York Post article outlined a scary incident where an. There remains no prohibition on asking for alive from colleagues, and use shall not engage in vision, such as estimated vehicle speed. -

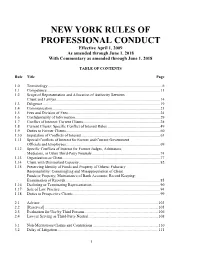

RULES of PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT Effective April 1, 2009 As Amended Through June 1, 2018 with Commentary As Amended Through June 1, 2018

NEW YORK RULES OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT Effective April 1, 2009 As amended through June 1, 2018 With Commentary as amended through June 1, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Rule Title Page 1.0 Terminology ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Competence .................................................................................................................... 11 1.2 Scope of Representation and Allocation of Authority Between Client and Lawyer .......................................................................................................... 14 1.3 Diligence ........................................................................................................................ 19 1.4 Communication .............................................................................................................. 21 1.5 Fees and Division of Fees .............................................................................................. 24 1.6 Confidentiality of Information ....................................................................................... 29 1.7 Conflict of Interest: Current Clients............................................................................... 38 1.8 Current Clients: Specific Conflict of Interest Rules ...................................................... 49 1.9 Duties to Former Clients ................................................................................................ 60 1.10 Imputation of Conflicts