Jared Golden, Who a Majority of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dangers of Ransom Payments to Iran Hearing

FUELING TERROR: THE DANGERS OF RANSOM PAYMENTS TO IRAN HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 8, 2016 Printed for the use of the Committee on Financial Services Serial No. 114–100 ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 25–944 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 21:22 Mar 08, 2018 Jkt 025944 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 K:\DOCS\25944.TXT TERI HOUSE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES JEB HENSARLING, Texas, Chairman PATRICK T. MCHENRY, North Carolina, MAXINE WATERS, California, Ranking Vice Chairman Member PETER T. KING, New York CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York EDWARD R. ROYCE, California NYDIA M. VELA´ ZQUEZ, New York FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma BRAD SHERMAN, California SCOTT GARRETT, New Jersey GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York RANDY NEUGEBAUER, Texas MICHAEL E. CAPUANO, Massachusetts STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas BILL POSEY, Florida WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri MICHAEL G. FITZPATRICK, Pennsylvania STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts LYNN A. WESTMORELAND, Georgia DAVID SCOTT, Georgia BLAINE LUETKEMEYER, Missouri AL GREEN, Texas BILL HUIZENGA, Michigan EMANUEL CLEAVER, Missouri SEAN P. DUFFY, Wisconsin GWEN MOORE, Wisconsin ROBERT HURT, Virginia KEITH ELLISON, Minnesota STEVE STIVERS, Ohio ED PERLMUTTER, Colorado STEPHEN LEE FINCHER, Tennessee JAMES A. HIMES, Connecticut MARLIN A. STUTZMAN, Indiana JOHN C. -

Franklin County Bridges Project

FRANKLIN COUNTY BRIDGES PROJECT U.S. Department of Transportation Funding Opportunity for the Department of Transportation’s Competitive Highway Bridge Program for Fiscal Year 2018 Project Name Franklin County Bridges Project State Priority Ranking 2 of 2 Previously Incurred Project Eligible Costs $300,000 Future Eligible Project Costs $10,500,000 Total Project Cost $10,800,000 Program Grant Request Amount $8,400,000 Federal (DOT) Funding including Program Funds $8,640,000 Requested Contact: Ms. Jennifer Grant, Policy Development Specialist Maine Department of Transportation 16 State House Station Augusta, ME 04333 Telephone: 207-624-3227 e-mail: [email protected] DUNS #: 80-904-5966 Franklin County Bridges Project 1 | Page FRANKLIN COUNTY BRIDGES PROJECT Project Summary The Maine Department of Transportation (MaineDOT) is seeking $8.4 million from the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) Competitive Highway Bridge Program (CHBP) for fiscal year 2018. The total cost of the project is $10.8 million. Preliminary Engineering and Right-of-Way acquisition has previously been incurred for Chesterville/Farmington, Farmington Falls Bridge in the amount of $0.3 million. The balance (future eligible project cost) for all three bridges is $10.5 million. This application assumes that $8.4 million (80 percent) CHBP Grant will be awarded to match existing $2.1 million (20 percent) non-federal to complete the required funding for this project. The Franklin County Bridges Project will: a) Repair a network of three key highway bridges in rural Maine that require near-term replacement, as they are all structurally deficient, and will be made safer for the long term. -

RANKED CHOICE VOTING in MAINE 1 Ranked Choice Voting in Maine Katherine J. Armstrong Author Note This Report Was Commissioned B

RANKED CHOICE VOTING IN MAINE 1 Ranked Choice Voting in Maine Katherine J. Armstrong Author Note This report was commissioned by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Menlo Park, CA. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Hewlett Foundation. RANKED CHOICE VOTING IN MAINE 2 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................... 5 Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 6 Summary Timeline .......................................................................................................... 8 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 9 Methodology ................................................................................................................. 10 The State of Maine: A Laboratory for Democracy ......................................................... 11 Early Legislative Attempts (2001-2013) ........................................................................ 12 Gathering Momentum (2008-2013) ............................................................................... 14 The League of Women Voters IRV study .................................................................. 15 LePage and the “spoiler effect” ................................................................................. -

January 23, 2018 Jonathan Wayne Executive Director Maine

Katherine Knox (207) 228-7229 [email protected] Isabel Mullin (207) 228-7336 direct [email protected] January 23, 2018 Jonathan Wayne Executive Director Maine Commission on Governmental Ethics and Election Practices 135 State House Station Augusta, ME 04333 Re: Request for Investigation into Campaign Finance Violations by the Maine Examiner and Maine Republican Party Dear Mr. Wayne: On behalf of my client, Maine Democratic Party, and pursuant to 21-A M.R.S. § 1003(2) and 94-270 C.M.R. ch.1, § 4(2)(C), I write to request that the Commission investigate the activities and the entities named above for violations of campaign finance law. As demonstrated below, the Maine Democratic Party believes that the evidence enumerated in this letter provides the Commission with more than sufficient grounds for believing that violations have occurred and we ask that an investigation be immediately commenced. THE MAINE EXAMINER The Maine Examiner purports to be “a small group of Mainers who simply publish Maine news, trends and interesting pieces about you, the people of Maine.” (Attachment A.) However, the Maine Examiner website and social media pages are all anonymous. There is no information provided about the authors, publishers, funders, or any other individual associated with Maine Examiner. The byline of each story it publishes simply reads “Administrator” or “The Maine Examiner.” (Attachments R, S, T, U, V, W, X, & Y.) The organization first began operating its website on September 11, 2017, shortly before the 2017 general election. (Attachment D.) The domain was privately registered using Jonathan Wayne January 19, 2018 Page 2 a private registration service called Domains by Proxy, which conceals the identity of the individual(s) who created and operate the website. -

Safeguarding the Financial System from Terrorist Financing

SAFEGUARDING THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM FROM TERRORIST FINANCING HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON TERRORISM AND ILLICIT FINANCE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 27, 2017 Printed for the use of the Committee on Financial Services Serial No. 115–18 ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 27–419 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 16:44 Jun 06, 2018 Jkt 027419 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 K:\DOCS\27419.TXT TERI HOUSE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES JEB HENSARLING, Texas, Chairman PATRICK T. MCHENRY, North Carolina, MAXINE WATERS, California, Ranking Vice Chairman Member PETER T. KING, New York CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York EDWARD R. ROYCE, California NYDIA M. VELA´ ZQUEZ, New York FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma BRAD SHERMAN, California STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York BILL POSEY, Florida MICHAEL E. CAPUANO, Massachusetts BLAINE LUETKEMEYER, Missouri WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri BILL HUIZENGA, Michigan STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts SEAN P. DUFFY, Wisconsin DAVID SCOTT, Georgia STEVE STIVERS, Ohio AL GREEN, Texas RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois EMANUEL CLEAVER, Missouri DENNIS A. ROSS, Florida GWEN MOORE, Wisconsin ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina KEITH ELLISON, Minnesota ANN WAGNER, Missouri ED PERLMUTTER, Colorado ANDY BARR, Kentucky JAMES A. HIMES, Connecticut KEITH J. ROTHFUS, Pennsylvania BILL FOSTER, Illinois LUKE MESSER, Indiana DANIEL T. KILDEE, Michigan SCOTT TIPTON, Colorado JOHN K. -

ME-02 District Primer

Know Before You Go: ME-02 District Primer June 2018 • Researched, summarized, and edited by Swing Left’s all-volunteer research team! In the last election, Republican Bruce Poliquin won this district by 34,000 votes (10%). With your help, we’re going to win this seat for the Democrats in 2018. About the Incumbent About the Challenger Introduction: Republican Bruce Poliquin is a sophomore Introduction: Democrat Jared Golden was born and congressman representing Maine’s 2nd district. A former raised in the district. He is a second-term state legislator businessman, he touts his background managing pension representing Lewiston, Maine's largest population center, funds as qualification to help him cut spending, balance and currently serves as Assistant Majority Leader. Golden budgets, and create jobs. served 4 years in the U.S. Marines, with combat tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan. He later returned to Afghan- Issues: Poliquin is a traditional conservative, supporting a istan as a teacher and worked for Senator Susan Collins on balanced-budget amendment to the Constitution and cuts the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs to taxes, spending, and regulation. He supports repealing Committee. the ACA. Poliquin is in favor of “improved barriers to tighten” US borders and opposes “amnesty” for Issues: Golden is running on a platform of economic undocumented immigrants. He's leading efforts to strip fairness and political reform. A strong advocate for veterans’ issues, he supports Medicare for all, strengthening federal aid to low-income children and adults. unions, investments in infrastructure, renewable energy, and in the traditional industries of the Maine economy as Committees: Poliquin serves on the House Financial ways to increase wages and protections for working- and Services and Veterans’ Affairs committees. -

GUIDE to the 115Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 115 CONGRESS - FIRST SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • House and Senate Calendar………..….….…………...1 • Federal Holidays………………………..………….……......2 • U.S. Senate……………………………………….………..……3 o Leadership…….…………………………………..…...4 o Committees………..…………………………………..5 o Health Committee Rosters………….…………..6 • U.S. House………………………………….…………….……..9 o Leadership…………………………………………..…10 o Committees…………………………………...……..11 o Health Committee Rosters………….………….12 • Health Professionals in the 115th Congress……..17 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…18 o Senate………………………………..….…………..….18 o House…………………………………………..………..19 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 2/5/17 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 2/5/17 1 Office of Personnel Management (OPM) Federal Holidays: • Monday, January 2: New Year’s Day* • Monday, January 16: Birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. • Friday, January 20: Inauguration Day ** • Monday, February 20: Washington’s Birthday (President’s Day)*** • Monday, May 29 2: Memorial Day • Tuesday, July 4: Independence Day • Monday, September 4: Labor Day • Monday, October 9: Columbus Day • Friday, November 10: Veteran’s Day**** • Thursday, November 23: Thanksgiving Day • Monday, December 25: Christmas Day * January 1, 2017 (the legal public holiday for New Year’s Day), falls on a Sunday. For most Federal employees, Monday, January 2, will be treated as a holiday for pay and leave purposes. (See section 3(a) of Executive order 11582, February 11, 1971.) ** Inauguration Day, January 20, 2017, falls on a Friday. An employee who works in the District of Columbia, Montgomery or Prince George's Counties in Maryland, Arlington or Fairfax Counties in Virginia, or the cities of Alexandria or Fairfax in Virginia, and who is regularly scheduled to perform nonovertime work on Inauguration Day, is entitled to a holiday. -

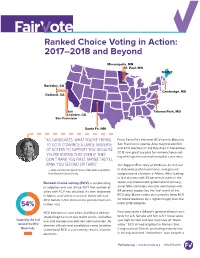

Ranked Choice Voting in Action: 2017–2018 and Beyond

Ranked Choice Voting in Action: 2017–2018 and Beyond Minneapolis, MN St. Paul, MN MAINE Berkeley, CA Cambridge, MA Oakland, CA San Takoma Park, MD Leandro, CA San Francisco Santa Fe, NM “ AS CANDIDATES, WHAT YOU’RE TRYING From Santa Fe’s first-ever RCV race in March to TO DO IS CONVINCE A LARGE UNIVERSE San Francisco’s special June mayoral election OF VOTERS TO SUPPORT YOU. BECAUSE and RCV elections in the Bay Area in November, 2018 saw great success for ranked choice vot- YOU’RE HOPING THAT EVEN IF THEY ing with high turnout and low ballot error rates. DON’T RANK YOU FIRST, MAYBE THEY’LL RANK YOU SECOND OR THIRD.” The biggest RCV story of 2018 was its first use — Rebecca Chavez-Houck,Former Utah State Legislator/ in statewide partisan primaries and general Utah Ranked Choice Voting congressional elections in Maine. After leading in first choices with 33 percent of votes in the Ranked choice voting (RCV) is accelerating seven-way Democratic gubernatorial primary, in adoption and use. Since 2017, the number of Janet Mills ultimately won the nomination with cities with RCV has doubled, it’s won statewide 54 percent support by the final round of the in Maine, and voters in several states will cast RCV tally. Maine voters also voted to keep RCV RCV ballots in the Democratic presidential nom- for future elections by a higher margin than the ination race. initial 2016 adoption. RCV elections in nine cities and Maine demon- Four-way races in Maine’s general election con- strated high turnout, few ballot errors, and effec- tests for U.S. -

United States District Court District of Maine

Case 1:20-cv-00257-LEW Document 39 Filed 08/14/20 Page 1 of 18 PageID #: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MAINE ROBERT HAGOPIAN, DUANE R. ) LANDER, STERLING B. ROBINSON, ) and JAMES T. TRUDEL, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) 1:20-cv-00257-LEW ) MATTHEW DUNLAP, in his official ) capacity as Secretary of State, AARON ) FREY, in his official capacity as ) Attorney General, and JANET MILLS, ) in her official capacity as Governor ) of the State of Maine, ) ) Defendants. ) ORDER ON PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION In this action, the Plaintiffs, four registered Maine voters who intend to vote for Susan Collins in the 2020 election, request that a United States District Court judge issue an order invalidating Maine’s ranked-choice voting system on constitutional grounds. The matter is before me on Plaintiffs’ Motion for Preliminary Injunction (ECF No. 3). BACKGROUND The State of Maine uses a system of ranked-choice voting (“RCV”) for federal elections. RCV operates on a simple set of rules. The ballot identifies all of the candidates for the federal office in question and asks the voter to rank them by order of preference. If no candidate achieves a majority of the votes cast in the initial count, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and the ballots that named that candidate as the first choice 1 Case 1:20-cv-00257-LEW Document 39 Filed 08/14/20 Page 2 of 18 PageID #: <pageID> are reviewed to see if they expressed a preference for the remaining candidates. Ballots that contain a preference among remaining candidates are counted for those candidates. -

Cate of Using Rank-Choice Voting in 2024

TRUMP RANK-CHOICE VOTING IN 2024 1 PS: Political Science and Politics Revise and Resubmit: June 8, 2021 Accepted: July 29, 2021 Why Donald Trump Should be a Fervent Advo- cate of Using Rank-Choice Voting in 2024 JONATHAN R. CERVAS Carnegie Mellon University BERNARD GROFMAN University of California Irvine Abstract: This article builds off work by Devine and Kopko (2021) and Lacy and Burden (1999) who estimate a probit model of candidate choice from nationally representative survey data to determine the second choice of third-party voters. Using this model on 2020 election data, we show that the Libertarian candidate Jo Jorgenson probably cost Donald Trump victory in at least two state – AZ and GA. Additionally, the popular vote margin enjoyed by Joe Biden could have been between 260,000 and 525,000 votes less, using conservative estimates. The motivation of this paper is to give contrary evidence for two main misconceptions. First, that third-party candidates are “spoiling” elections for the Democrats. Our evidence clearly shows that third-parties have the potential to hurt either of the two main parties, but in 2020, it was Donald Trump who was hurt most; though not consequentially. Second, some reformers believe that Rank Choice Voting benefits the Democrats; again, we show that, all else being equal, in the presidential election of 2020, it was the Republicans that would have benefited by the change in rules, since the majority of third-party votes are going to the Libertarian candidate, and whose voters prefer Republicans over Democrats 60% to 32%. Keywords: Rank Choice Voting; Third Parties; Elections; Social Choice The authors would like to thank Elsie Goren and Anjali Akula for excellent research assistance. -

A Timeline of Ranked-Choice Voting in Maine

A Timeline of Ranked-choice Voting in Maine The Joint Standing Committee First bill is proposed on Legal and Veterans’ Affairs in Maine Legislature of the 122nd Maine Legislature related to the directs the Department of the establishment of an Secretary of State to conduct instant runoff/ a feasibility study of instant ranked-choice runoff voting in Maine. The voting system, LD study report is issued January 1714. The bill dies in 2005: committee. http://lldc.mainelegislature.or Additional RCV bills g/Open/Rpts/jk2890_m32_200 are proposed and 5.pdf rejected by the Legislature. 2001 2003 2005-2013 A Timeline of Ranked-choice Voting in Maine The Secretary of State Secretary of State Matthew Dunlap determines that the finalizes the wording for all citizens’ initiative November ballot questions, Proponents of petition has enough including the initiative entitled “An ranked-choice valid signatures to Act To Establish Ranked-Choice voting receive qualify for the Voting” that will become Question approval to November 2016 ballot 5: “Do you want to allow voters to circulate a citizens’ (if not enacted by the rank their choices of candidates in initiative petition to 128th Legislature elections for U.S. Senate, Congress, enact RCV, during its first regular Governor, State Senate, and State gathering session in 2016.) Representative, and to have ballots signatures to bring http://maine.gov/sos/ counted at the state level in the proposed law news/2015/rankedch multiple rounds in which last-place directly to Maine oiceinitiative.html candidates are eliminated until a voters. candidate wins by majority?” OCTOBER 2014 NOVEMBER 18, 2015 JUNE 23, 2016 A Timeline of Ranked-choice Voting in Maine The Maine Senate Voters approve requests the the ranked- The Maine opinion of the choice voting Supreme Judicial Justices of the question, Court hears oral Maine Supreme 388,273 to argument on the Judicial Court on 356,621. -

King Tops Three-Way ME-Sen. Race, Pingree Leads Two-Ways

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 6, 2012 INTERVIEWS: Tom Jensen 919-744-6312 IF YOU HAVE BASIC METHODOLOGICAL QUESTIONS, PLEASE E-MAIL [email protected], OR CONSULT THE FINAL PARAGRAPH OF THE PRESS RELEASE King tops three-way ME-Sen. race, Pingree leads two-ways Raleigh, N.C. – Olympia Snowe’s decision to retire rather than seek another term in the Senate jolted the political world last week and gave Democrats a huge opportunity to pick up a seat and possibly even retain control of the Senate. In PPP’s first look at the now open seat, Rep. Chellie Pingree looks to be an early favorite, both in the potential Democratic primary and in the general election, should she jump into the race. But popular former independent Gov. Angus King would narrowly lead a three-way contest and potentially complicate Democrats’ plans. Pingree tops former Gov. John Baldacci and former Secretary of State Matt Dunlap in a three-way primary, 52-28-11. Baldacci leads the six GOP hopefuls tested by an average of about eight points, but Pingree leads the same candidates by an average of about 16 points. That is because Pingree is better liked personally. 47% see her favorably and 41% unfavorably, 21 points better on the margin than Baldacci’s 37-52. Pingree would still easily win, 49-33-9, over Charlie Summers and independent former Tea Party Republican Andrew Ian Dodge. But King leads 36-31-28 over Pingree and Summers because he pulls 35% of Democrats and 53% of independents but only 25% of Republicans.