All (Washed) Hands on Deck: How to Help Yourself & Others

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludology with Dr. Jane Mcgonigal Ologies Podcast March 12, 2019

Ludology with Dr. Jane McGonigal Ologies Podcast March 12, 2019 Ohaaay, it’s the lady sitting in the middle seat, who has to get up to pee, but you’re in the window seat and you’re so relieved she does, because that means you don’t have to ask the guy in the aisle to get up, Alie Ward, back with another episode of Ologies. Oh, video games! [Mario coin-collecting noise] Video games, what’s their deal? How do they affect our brains? Have we got an ology for y’all! First, I do have some thanks. Thanks to everyone who’s pledging some of your latte money or tossing me a quarter a week on Patreon for making it possible for me to get my physical butt in the same space as the ologists, or in this case, pay a recording studio to do our first ever remote interview. Very exciting. Thanks to everyone sporting Ologies merch out in the wild – that’s at OlogiesMerch.com. T-shirts, hats, pins, all of that. Thank you to everyone who rates, and subscribes, and reviews. You leave such nice notes! For example, Namon says: I love this podcast so much. I found it when searching for podcasts to sleep! Sadly, I found a podcast to binge and stay up even later. Thank you, Alie Ward, for the podcast that has everything from biology to beauty. I never did solve my sleeping problem, but I don’t really mind anymore, so thank you for the podcast. Well, thanks for the review! Try the Fancy Nancy. -

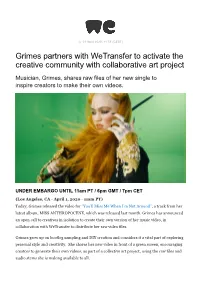

Grimes Partners with Wetransfer to Activate the Creative Community with Collaborative Art Project

⏲ 01 April 2020, 11:55 (CEST) Grimes partners with WeTransfer to activate the creative community with collaborative art project Musician, Grimes, shares raw files of her new single to inspire creators to make their own videos. UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 11am PT / 6pm GMT / 7pm CET (Los Angeles, CA - April 1, 2020 - 11am PT) Today, Grimes released the video for “You’ll Miss Me When I’m Not Around”, a track from her latest album, MISS ANTHROPOCENE, which was released last month. Grimes has announced an open call to creatives in isolation to create their own version of her music video, in collaboration with WeTransfer to distribute her raw video files. Grimes grew up on bootleg sampling and DIY creation and considers it a vital part of exploring personal style and creativity. She shares her new video in front of a green screen, encouraging creators to generate their own videos, as part of a collective art project, using the raw files and audio stems she is making available to all. Grimes shares, “Because we’re all in lockdown we thought if people are bored and wanna learn new things, we could release the raw components of a music video for anyone who wants to try making stuff using our footage." WeTransfer’s Head of Music, Tiff Yu adds, “Grimes has always been a fan of collaboration and open source creativity. This project is a great opportunity to let your mind run wild and free, within any creative field. With no limitations, timing or restrictions, she’s made a project for where creatives can be truly creative, without worrying about any red tape or timing.” WeTransfer is embedded within the creative industries and is helping Grimes activate the creative community through their audience. -

Psephology with Dr

Psephology with Dr. Michael Lewis-Beck Ologies Podcast November 2, 2018 Oh heyyyy, it's that neighborhood lady who wears pantyhose with sandals and hosts a polling place in her garage with a bowl of leftover Halloween candy, Alie Ward! Welcome to this special episode, it's a mini, and it's a bonus, but it's also the first one I've ever done via telephone. Usually, I drag myself to a town and I make an ologist meet me in a library, or a shady hotel, and we record face to face, but time was of the essence here. He had a landline, raring to chat, we went for it. I did not know this ology was an ology until the day before we did this interview. Okay, we're gonna get to it. As always, thank you, Patrons for the for fielding my post, “hey, should I record a really quick voting episode this week?” with your resounding yeses. I love you, thank you for supporting the show. OlogiesMerch has shirts and hats if you need ‘em. And thank you everyone for leaving reviews and ratings, including San Rey [phonetic] who called this podcast, “Sherlock Holmes dressed in street wear.” I will take that. Also, you're assuming that I'm wearing pants... Quick plug also, I have a brand new show on Netflix that dropped today! It's called Brainchild, it's produced by Pharrell Williams and the folks at Atomic Entertainment. I’m in every episode popping up to explain science while also wearing a metallic suit and a beehive. -

The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences

1 THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES NOMINATIONS FOR THE 46th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS Daytime Emmy Awards to be held on Sunday, May 5th Daytime Creative Arts Emmy® Awards Gala on Friday, May 3rd Both Events Take Place at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium in Southern California New York – March 20, 2019 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 46th Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards. The ceremony will be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Sunday, May 5, 2019. The Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Awards will also be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Friday, May 3, 2019. The 46th Annual Daytime Emmy Award Nominations were revealed today on the Emmy Award-winning show The Talk on CBS. “We are very excited today to announce the nominees for the 46th Annual Daytime Emmy Awards,” said, Adam Sharp, President & CEO of The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). “We look forward to a grand celebration honoring the best of Daytime television both in front of the camera and behind as we return for the third year in a row to the classic Pasadena Civic Auditorium.” “The incredible level of talent and craft reflected in our nominees continues to show the growing impact of Daytime television and the incredible diversity of programming the viewing audience has to choose from,” said, Executive Director, Daytime, Brent Stanton. “With the help of some outstanding new additions to our staff, Rachel Schwartz and Lisa Armstrong, and the continued support of Luke Smith and Christine Chin, we have handled another record-breaking number of entries this year. -

Molecular Neurobiology with Dr. Crystal Dilworth Ologies Podcast November 12, 2019

Molecular Neurobiology with Dr. Crystal Dilworth Ologies Podcast November 12, 2019 Oh heeey, it’s the lady who keeps candles in her wallet because you never know when you’ll be in a pinch and it’s going to be someone’s birthday, and you’ll be more excited about singing to them than they’ll be excited about being sung to, Alie Ward, back with another episode of Ologies. You like brains? Does your brain like brains? It probably does. Right now, your soft squishy think-lump is just hanging out in your head, thinking about itself. How does it work? What’s in there? Why do I want to eat Cool Whip out of the tub with my fingers? And why aren’t I more excited about folding my laundry? The answer: molecular neurobiology. But before we splish-splash into your mood juices, let’s take care of some business up top and thank all the folks on Patreon.com/Ologies for being in the club. Y’all support the show and hear what topics I’m working on first and you submit your questions for the ologists. Thanks to everyone wearing Ologies merch from OlogiesMerch.com. Thanks to everyone who forwards an episode to a friend or who subscribes on their devices, and rates, and especially reviews, because you know I read your words and pick a freshie to put on blast, such as Dusqkee who said they’re falling back in love with life and that: … the ologists have shown me the light. The world is a beautiful place and with all these smart monkeys out there maybe, just maybe, we have a chance to share it with future generations! P.S. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 107 MARCH 23RD, 2020 Cover: violinist Jascha Heifetz (1901 - 1987). Many consider him to be the greatest violinist ever. He was one of the most influential performing artists of all time and in his later years became a teacher and an advocate of causes he believed in, including clean air and the establishment of 911 as an emergency phone number. Stay safe. Be careful out there. Maintain social distancing. Wash your hands frequently. Familiar phrases in these tough times. To those I’d add: listen to music. Read a book or magazine. Watch a movie. Play your instrument. Surf the web. Don’t let the endless barrage of TV news make you crazy. Ignore (except to debunk) misinformation on Facebook and social media. Call or video chat with a family member, friend or loved one. Though we may be temporarily separated, we’re all in this together and we’ll help each other stay strong. In this issue: Anne E. Johnson gives us incisive looks into two of the modern era’s greatest artists: Frank Sinatra and the Kinks! John Seetoo contributes his CanJam NYC 2020 Part Two report. J.I. Agnew continues his series on linearity in audio, with clear explanations of this technical topic. Tom Gibbs gives unrestrained opinions on Brandy Clark, King Crimson, Charlie Parker and Tame Impala. Professor Larry Schenbeck enthuses about Sanctuary Road, a new oratorio. Dan Schwartz asks: why don’t musicians use audiophile speakers? Veteran broadcaster Bob Wood shakes his head over the state of today’s commercial radio. Wayne Robins provides a step by step operating manual for Miss Anthropocene by Grimes. -

Links Away the Institution’S Forward to the Present Day

Gain perspective. Get inspired. Make history. THE HENRY FORD MAGAZINE - JUNE-DECEMBER 2019 | SPACESUIT DESIGN | UTOPIAN COMMUNITIES | CYBERFORMANCE | INSIDE THE HENRY FORD THE HENRY | INSIDE COMMUNITIES | CYBERFORMANCE DESIGN | UTOPIAN | SPACESUIT 2019 - JUNE-DECEMBER MAGAZINE FORD THE HENRY MAGAZINE JUNE-DECEMBER 2019 THE PUSHING BOUNDARIES ISSUE What’s the unexpected human story behind outerwear for outer space? UTOPIAN PAGE 28 OUTPOSTS OF THE ‘60S, ‘70S THE WOMEN BEHIND THEATER PERFORMED VIA DESKTOP THE HENRY FORD 90TH ANNIVERSARY ARTIFACT TIMELINE Gain perspective. Get inspired. Make history. THE HENRY FORD MAGAZINE - JUNE-DECEMBER 2019 | SPACESUIT DESIGN | UTOPIAN COMMUNITIES | CYBERFORMANCE | INSIDE THE HENRY FORD THE HENRY | INSIDE COMMUNITIES | CYBERFORMANCE DESIGN | UTOPIAN | SPACESUIT 2019 - JUNE-DECEMBER MAGAZINE FORD THE HENRY MAGAZINE JUNE-DECEMBER 2019 THE PUSHING BOUNDARIES ISSUE What’s the unexpected human story behind outerwear for outer space? UTOPIAN PAGE 28 OUTPOSTS OF THE ‘60S, ‘70S THE WOMEN BEHIND THEATER PERFORMED VIA DESKTOP THE HENRY FORD 90TH ANNIVERSARY ARTIFACT TIMELINE HARRISBURG PA HARRISBURG PERMIT NO. 81 NO. PERMIT PAID U.S. POSTAGE U.S. PRSRTD STD PRSRTD ORGANIZATION ORGANIZATION NONPROFIT NONPROFIT WHEN IT’S TIME TO SERVE, WE’RE ALL SYSTEMS GO. Official Airline of The Henry Ford. What would you like the power to do? At Bank of America we are here to serve, and listening to how people answer this question is how we learn what matters most to them, so we can help them achieve their goals. We had one of our best years ever in 2018: strong recognition for customer service in every category, the highest levels of customer satisfaction and record financial results that allow us to keep investing in how we serve you. -

(IP REPORT) - February 1, 2020 Through February 29, 2020 Subject Key No

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - February 1, 2020 through February 29, 2020 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 5 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 84 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 159 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 89 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 98 EDUCATION 24 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 32 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 145 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 24 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 370 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 83 RELIGION 15 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 44 Total Story Count 1172 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 103:31:58 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 520 Fresh Air FA 38 Morning Edition ME 407 TED Radio Hour TED 0 Weekend Edition WE 207 Total Story Count 1172 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 103:31:58 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 02/24/2020 0:04:23 How Some Are Trying To Teach Senior Citizens To Spot Fake News Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 02/19/2020 0:04:47 Lax Regulations And Vulnerable Residents 'A Recipe For Problems' In Eldercare Homes Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 02/11/2020 0:03:50 Puerto Rico Reaches Tentative Deal To Restructure Debt Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 02/10/2020 0:07:01 Why -

Full) Robert Nguyen Ulrich

Last updated: 16 March 2021 Curriculum Vitae (Full) Robert Nguyen Ulrich 4th-year Biogeochemistry Ph.D. student | Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) email: [email protected] | site: https://www.robertnulrich.com/ Education University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Expected 2022 Ph.D., Biogeochemistry University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) 2019 M.S., Geochemistry Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University (Virginia Tech) 2017 B.S., Chemistry B.S., Geosciences (concentration: Geochemistry) Research & Training Experience UCLA Climate and Biogeochemistry Lab – Advisors, Drs. Aradhna 2017 - Present Tripati & Rob Eagle S.S. Papadopulos & Associates, Inc., Bethesda, MD – Supervisor, Dr. June – September 2017 Keir Soderberg 1) Analyzed polychlorinated biphenyl distribution in the environment using fugacity models; 2) Developed a framework for stable isotope mixing models for perchlorate contaminated sites; 3) Juxtaposed EPA analysis methods for assessing naphthalene concentrations in water; 4) Compiled and analyzed the interactions of recycled concrete aggregates with groundwater Virginia Tech Biogeochemistry of Earth Materials – Advisor, Dr. Patricia 2015 - 2017 Dove Virginia Tech Sedimentary Systems Lab – Advisor, Dr. Brian Romans August – December 2014 Petrographic characterization of axial versus marginal submarine channel sandstones, Tres Pasos Formation Honors & Awards (~$174,000+) National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow ($138,000) 2018 - Present Center -

45Th Annual Daytime Emmy Award Nominations Were Revealed Today on the Emmy Award-Winning Show, the Talk, on CBS

P A G E 1 6 THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES NOMINATIONS FOR THE 45th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS Mario Lopez & Sheryl Underwood to Host Daytime Emmy Awards to be held on Sunday, April 29 Daytime Creative Arts Emmy® Awards Gala on Friday, April 27 Both Events to Take Place at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium in Southern California New York – March 21, 2018 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 45th Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards. The ceremony will be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Sunday, April 29, 2018 hosted by Mario Lopez, host and star of the Emmy award-winning syndicated entertainment news show, Extra, and Sheryl Underwood, one of the hosts of the Emmy award-winning, CBS Daytime program, The Talk. The Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Awards will also be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Friday, April 27, 2018. The 45th Annual Daytime Emmy Award Nominations were revealed today on the Emmy Award-winning show, The Talk, on CBS. “The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences is excited to be presenting the 45th Annual Daytime Emmy Awards, in the historic Pasadena Civic Auditorium,” said Chuck Dages, Chairman, NATAS. “With an outstanding roster of nominees and two wonderful hosts in Mario Lopez and Sheryl Underwood, we are looking forward to a great event honoring the best that Daytime television delivers everyday to its devoted audience.” “The record-breaking number of entries and the incredible level of talent and craft reflected in this year’s nominees gives us all ample reasons to celebrate,” said David Michaels, SVP, and Executive Producer, Daytime Emmy Awards. -

Download Magazine

Magazine Issue Porsche Engineering 2/2021 www.porsche-engineering.com THE PATH TO THE AUTOMOTIVE FUTURE Intelligent . Connected. Digital Technically it’s an electric car. But it’s actually fuelled by adventure. The new Taycan Cross Turismo. Soul, electrified. Electricity consumption (in kWh/ km) combined .; CO₂ emissions (in g/km) combined Porsche Engineering Magazine 2/2021 Editorial 3 dear reader, A pioneering spirit has shaped Porsche’s history from its very inception. This is just as true for engineering services by Porsche as it is for the sports car manufacturer Porsche. Since the founding of the Porsche engineering office 90 years ago, we have dedicated ourselves to technical challenges with passion and inventiveness. Our aim is always to develop the innovations of tomorrow. What Ferdinand Porsche began with pioneering work such as the Volkswagen, we are carrying forward today with the development of technologies for the intelligent and connected vehicle of the future. In the process, we pay close attention to specific market requirements for digital functions. Hence the theme of the current issue of our magazine: "Intelligent. Connected. Digital". Our report on the Big Data Loop shows the potential that artificial intelligence holds in store for new driving functions. Learning in the cloud will make it possible to optimize driving functions largely auto- matically even after a vehicle has been delivered, thus offering customers added value. What we were able to demonstrate in the proof of concept using the example of adaptive cruise control will be of interest for many other driving functions as well. The Big Data Loop is also a good example of the increasing importance of connectivity. -

Avian Rhetoric, Murmurations by Melissa T. Yang Bachelor of Arts, Mount Holyoke College, 2011 Master of Arts, University of Pitt

Avian Rhetoric, Murmurations by Melissa T. Yang Bachelor of Arts, Mount Holyoke College, 2011 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Melissa T. Yang It was defended on June 14, 2019 and approved by Troy Boone, Associate Professor, Department of English Peter Trachtenberg, Associate Professor, Department of English John Walsh, Associate Professor, Department of French & Italian Languages & Literatures Dissertation Co-Advisors: Cory Holding, Assistant Professor, Department of English Annette Vee, Associate Professor, Department of English ii Copyright © by Melissa T. Yang 2019 iii Avian Rhetoric, Murmurations Melissa T. Yang, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 This dissertation explores the omnipresent role birds play in the English language and in Western cultural history. Reading and weaving across academic discourse, multi-genre literature, and obsolete and everyday figures, I examine the multiplicity of ways in which birds manifest and are embedded in modes and materialities of human composing and communicating. To apply Anne Lamott’s popular advice of writing “bird by bird” literally/liberally, each chapter shares stories of a species, family, or flock of birds. Believing in the enduring rhetorical power of narrative assemblages over explicit thetic arguments, I’ve modeled this project on the movements of flocked birds. I initially proposed and now offer a prosed assembly of avian figures following each other in flight, swerving fluidly across broad and varied landscapes while maintaining elastic, organic connections.