The Great Bend of the Gila (25-1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lower Gila Region, Arizona

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HUBERT WORK, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 498 THE LOWER GILA REGION, ARIZONA A GEOGBAPHIC, GEOLOGIC, AND HTDBOLOGIC BECONNAISSANCE WITH A GUIDE TO DESEET WATEEING PIACES BY CLYDE P. ROSS WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1923 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAT BE PROCURED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 50 CENTS PEE COPY PURCHASER AGREES NOT TO RESELL OR DISTRIBUTE THIS COPT FOR PROFIT. PUB. RES. 57, APPROVED MAT 11, 1822 CONTENTS. I Page. Preface, by O. E. Melnzer_____________ __ xr Introduction_ _ ___ __ _ 1 Location and extent of the region_____._________ _ J. Scope of the report- 1 Plan _________________________________ 1 General chapters _ __ ___ _ '. , 1 ' Route'descriptions and logs ___ __ _ 2 Chapter on watering places _ , 3 Maps_____________,_______,_______._____ 3 Acknowledgments ______________'- __________,______ 4 General features of the region___ _ ______ _ ., _ _ 4 Climate__,_______________________________ 4 History _____'_____________________________,_ 7 Industrial development___ ____ _ _ _ __ _ 12 Mining __________________________________ 12 Agriculture__-_______'.____________________ 13 Stock raising __ 15 Flora _____________________________________ 15 Fauna _________________________ ,_________ 16 Topography . _ ___ _, 17 Geology_____________ _ _ '. ___ 19 Bock formations. _ _ '. __ '_ ----,----- 20 Basal complex___________, _____ 1 L __. 20 Tertiary lavas ___________________ _____ 21 Tertiary sedimentary formations___T_____1___,r 23 Quaternary sedimentary formations _'__ _ r- 24 > Quaternary basalt ______________._________ 27 Structure _______________________ ______ 27 Geologic history _____ _____________ _ _____ 28 Early pre-Cambrian time______________________ . -

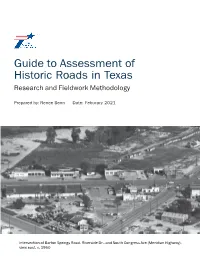

Guide to Assessment of Historic Roads in Texas Research and Fieldwork Methodology

Guide to Assessment of Historic Roads in Texas Research and Fieldwork Methodology Prepared by: Renee Benn Date: Feburary 2021 Intersection of Barton Springs Road, Riverside Dr., and South Congress Ave (Meridian Highway), view east, c. 1950 Table of Contents Section 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 Section 2 Context ........................................................................................................................... 5 County and Local Roads in the late 19th and early 20th centuries ........................................... 5 Named Auto Trails/Private Road Associations ........................................................................ 5 Early Development of the Texas Highway Department and U.S. Highway system .......................... 5 Texas Roads in the Great Depression and World War II ............................................................ 6 Post World War II Road Networks ........................................................................................... 6 Section 3 Research Guide and Methodology ............................................................................... 8 Section 4 Road Research at TxDOT ............................................................................................... 11 Procedural Steps .......................................................................................................... 11 Section 5 Survey Methods .......................................................................................................... -

Tribal Perspectives on the Hohokam

Bulletin of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center Tucson, Arizona December 2009 Number 60 Michael Hampshire’s artist rendition of Pueblo Grande platform mound (right); post-excavation view of compound area northwest of Pueblo Grande platform mound (above) TRIBAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE HOHOKAM Donald Bahr, Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, Arizona State University The archaeologists’ name for the principal pre-European culture of southern Arizona is Hohokam, a word they adopted from the O’odham (formerly Pima-Papago). I am not sure which archaeologist first used that word. It seems that the first documented but unpublished use is from 1874 or 1875 (Haury 1976:5). In any case, since around then archaeologists have used their methods to define and explain the origin, development, geographic extent, and end of the Hohokam culture. This article is not about the archaeologists’ Hohokam, but about the stories and explanations of past peoples as told by the three Native American tribes who either grew from or replaced the archaeologists’ Hohokam on former Hohokam land. These are the O’odham, of course, but also the Maricopa and Yavapai. The Maricopa during European times (since about 1550) lived on lands previously occupied by the Hohokam and Patayan archaeological cultures, and the Yavapai lived on lands of the older Hohokam, Patayan, Hakataya, Salado, and Western Anasazi cultures – to use all of the names that have been used, sometimes overlappingly, for previous cultures of the region. The Stories The O’odham word huhugkam means “something that is used up or finished.” The word consists of the verb huhug, which means “to be used up or finished,” and the suffix “-kam,” which means “something that is this way.” Huhug is generally, and perhaps only, used as an intransitive, not a transitive, verb. -

Southern Sinagua Sites Tour: Montezuma Castle, Montezuma

Information as of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center Presents: March 4, 2021 99 a.m.-5:30a.m.-5:30 p.m.p.m. SouthernSouthern SinaguaSinagua SitesSites Tour:Tour: MayMay 8,8, 20212021 MontezumaMontezuma Castle,Castle, SaturdaySaturday MontezumaMontezuma Well,Well, andand TuzigootTuzigoot $30 donation ($24 for members of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center or Friends of Pueblo Grande Museum) Donations are due 10 days after reservation request or by 5 p.m. Wednesday May 8, whichever is earlier. SEE NEXT PAGES FOR DETAILS. National Park Service photographs: Upper, Tuzigoot Pueblo near Clarkdale, Arizona Middle and lower, Montezuma Well and Montezuma Castle cliff dwelling, Camp Verde, Arizona 9 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Saturday May 8: Southern Sinagua Sites Tour – Montezuma Castle, Montezuma Well, and Tuzigoot meets at Montezuma Castle National Monument, 2800 Montezuma Castle Rd., Camp Verde, Arizona What is Sinagua? Named with the Spanish term sin agua (‘without water’), people of the Sinagua culture inhabited Arizona’s Middle Verde Valley and Flagstaff areas from about 6001400 CE Verde Valley cliff houses below the rim of Montezuma Well and grew corn, beans, and squash in scattered lo- cations. Their architecture included masonry-lined pithouses, surface pueblos, and cliff dwellings. Their pottery included some black-on-white ceramic vessels much like those produced elsewhere by the An- cestral Pueblo people but was mostly plain brown, and made using the paddle-and-anvil technique. Was Sinagua a separate culture from the sur- rounding Ancestral Pueblo, Mogollon, Hohokam, and Patayan ones? Was Sinagua a branch of one of those other cultures? Or was it a complex blending or borrowing of attributes from all of the surrounding cultures? Whatever the case might have been, today’s Hopi Indians consider the Sinagua to be ancestral to the Hopi. -

Great Bend of the Gila?

GreatWhat Is the Bend of the Gila? The Great Bend of the Gila is a fragile stretch of river valley and surrounding lands in the Sonoran Desert of southwestern Arizona. This rural landscape is nestled between the cities of Phoenix and Yuma. The Gila River flows through a series of pronounced “bends” here, past jagged mountains and extinct lava flows. It joins the Colorado River just north of the Sea of Cortez. For millennia, communities flourished along the Great Bend. People from many different walks of life created a cultural landscape that merges archaeo- logical and historical wonders in a remarkable natural setting. What Is Special about the Great Bend of the Gila? The Great Bend has long been a The valley later served as an over- crossroads where people of different land route between Spanish settle- backgrounds came together in inter- ments in Sonora and missions along esting and inspiring ways. This legacy the California coast. Father Eusebio of cultural diversity is literally written Kino blazed this trail in 1699, and on the landscape in the form of tens Juan Bautista de Anza formalized it of thousands of petroglyphs authored in 1775. It served as the foundation by Native Americans, with later for many subsequent transconti- additions by Spaniards, Mexicans, and nental trails and roads, including Euro-Americans. Kearny’s trail for the Army of the For more than 1,000 years, fam- West, Cooke's Wagon Road for the ilies lived in villages along the lower Mormon Battalion, and the Butterfield Gila River and cultivated ancestral Overland Stage Line. -

The Maricopa County Wildlife Connectivity Assessment: Report on Stakeholder Input January 2012

The Maricopa County Wildlife Connectivity Assessment: Report on Stakeholder Input January 2012 (Photographs: Arizona Game and Fish Department) Arizona Game and Fish Department In partnership with the Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................ i RECOMMENDED CITATION ........................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ iii DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................ iv BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................ 1 THE MARICOPA COUNTY WILDLIFE CONNECTIVITY ASSESSMENT ................................... 8 HOW TO USE THIS REPORT AND ASSOCIATED GIS DATA ................................................... 10 METHODS ..................................................................................................................................... 12 MASTER LIST OF WILDLIFE LINKAGES AND HABITAT BLOCKSAND BARRIERS ................ 16 REFERENCE MAPS ....................................................................................................................... -

A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum Pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, Or Independent Domestication

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1v84t8z1 Journal KIVA, 83(4) ISSN 0023-1940 Authors Graham, AF Adams, KR Smith, SJ et al. Publication Date 2017-10-02 DOI 10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California KIVA Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History ISSN: 0023-1940 (Print) 2051-6177 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ykiv20 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy To cite this article: Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy (2017): A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication, KIVA, DOI: 10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 View supplementary material Published online: 12 Oct 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ykiv20 Download by: [184.99.134.102] Date: 12 October 2017, At: 06:14 kiva, 2017, 1–29 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham1, Karen R. Adams2, Susan J. Smith3, and Terence M. -

Climate Change and Cultural Response in the Prehistoric American Southwest

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- Published Research US Geological Survey Fall 2009 Climate Change and Cultural Response In The Prehistoric American Southwest Larry Benson U.S. Geological Survey, [email protected] Michael S. Berry Bureau of Reclamation Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Benson, Larry and Berry, Michael S., "Climate Change and Cultural Response In The Prehistoric American Southwest" (2009). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 725. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/725 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- Published Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CLIMATE CHANGE AND CULTURAL RESPONSE IN THE PREHISTORIC AMERICAN SOUTHWEST Larry V. Benson and Michael S. Berry ABSTRACT Comparison of regional tree-ring cutting-date distributions from the southern Col- orado Plateau and the Rio Grande region with tree-ring-based reconstructions of the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) and with the timing of archaeological stage transitions indicates that Southwestern Native American cultures were peri- odically impacted by major climatic oscillations between A.D. 860 and 1600. Site- specifi c information indicates that aggregation, abandonment, and out-migration from many archaeological regions occurred during several widespread mega- droughts, including the well-documented middle-twelfth- and late-thirteenth- century droughts. We suggest that the demographic response of southwestern Native Americans to climate variability primarily refl ects their dependence on an inordinately maize-based subsistence regimen within a region in which agricul- ture was highly sensitive to climate change. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

Arizona Historic Bridge Inventory | Pages 164-191

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet section number G, H page 156 V E H I C U L A R B R I D G E S I N A R I Z O N A Geographic Data: State of Arizona Summary of Identification and Evaluation Methods The Arizona Historic Bridge Inventory, which forms the basis for this Multiple Property Documentation Form [MPDF], is a sequel to an earlier study completed in 1987. The original study employed 1945 as a cut-off date. This study inventories and evaluates all of the pre-1964 vehicular bridges and grade separations currently maintained in ADOT’s Structure Inventory and Appraisal [SI&A] listing. It includes all structures of all struc- tural types in current use on the state, county and city road systems. Additionally it includes bridges on selected federal lands (e.g., National Forests, Davis-Monthan Air Force Base) that have been included in the SI&A list. Generally not included are railroad bridges other than highway underpasses; structures maintained by federal agencies (e.g., National Park Service) other than those included in the SI&A; structures in private ownership; and structures that have been dismantled or permanently closed to vehicular traffic. There are exceptions to this, however, and several abandoned and/or privately owned structures of particular impor- tance have been included at the discretion of the consultant. The bridges included in this Inventory have not been evaluated as parts of larger road structures or historic highway districts, although they are clearly integral parts of larger highway resources. -

Central Arizona Salinity Study --- Phase I

CENTRAL ARIZONA SALINITY STUDY --- PHASE I Technical Appendix D HYDROLOGIC REPORT ON THE GILA BEND BASIN Prepared for: United States Department of Interior Bureau of Reclamation Prepared by: Brown and Caldwell 201 East Washington Street, Suite 500 Phoenix, Arizona 85004 D-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ 2 LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 4 2.0 PHYSICAL SETTING ....................................................................................................... 5 3.0 GENERALIZED GEOLOGY ............................................................................................ 6 3.1 BEDROCK GEOLOGY ......................................................................................... 6 3.2 BASIN GEOLOGY ................................................................................................ 6 4.0 HYDROGEOLOGIC CONDITIONS ................................................................................ 8 4.1 GROUNDWATER OCCURRENCE AND MOVEMENT ................................... 8 4.2 GROUNDWATER QUALITY ............................................................................. -

1. Presentación. 2.Fundamentación

1 UNIVERSIDAD VERACRUZANA INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES HISTORICO-SOCIALES INTRODUCCION A MESOMERICA Y NUEVOS DESCUBRIMIENTOS PROFR. DR. PEDRO JIMENEZ LARA I.I.H-S 1. Presentación. El presente curso pretende ofrecer una visión de los elementos y períodos culturales que identifican al México Antiguo. Las regiones son: oasisamérica, aridoamérica y mesoamérica Los horizontes que la componen son: arqueolítico, cenolítico inferior, cenolítico superior, protoneolítico, oasisamérica, aridoamérica, mesoamérica y los primeros contactos en el s. XVI: Planteamiento que se hace de esta manera para una mejor comprensión del curso y entender la evolución de los grupos asentados en territorio mexicano. 2.Fundamentación. Las área culturales del México Antiguo no solo se reduce a Mesoamérica como el período de máximo florecimiento que le antecedió a la conquista. En otros tiempos, antes de conocerse esta macroárea cultural, llegaron diversos grupos de cazadores-recolectores nómadas. El proceso evolutivo de estos grupos fue largo y lento, permitiendo avanzar e ir tocando diferentes niveles de desarrollo y los conocimientos necesarios para el cultivo y domesticación de las plantas como uno de los descubrimientos mas importantes durante esta fase que cambio el curso de la historia. Otra de las regiones es la llamada Oasisamérica localizada al sw de E.U. y norte de México, compuesta por grupos sedentarios agrícolas pero con una complejidad similar a la Mesoamericana. El área denominada mesoamérica, espacio donde interactuaron y se desarrollaron diversos grupos culturales, fue la “…sede de la mas alta civilización de la América precolombina. (Niederbeger, 11, 1996), se desarrollo en la mayor parte del territorio mexicano. Mesoamérica, definida así por Kirchhoff en 1943, es punto de referencia no solo para estudiosos del período prehispánico, en el convergen diversos especialistas amparados en diferentes corrientes ideológicas y enfoques: antropólogos, geógrafos prehistoriadores, historiadores, sociólogos, arquitectos, biólogos, sociólogos, por mencionar a algunos.