Biological Opinion and Conference Opinion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

Approved Plant List 10/04/12

FLORIDA The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago, the second best time to plant a tree is today. City of Sunrise Approved Plant List 10/04/12 Appendix A 10/4/12 APPROVED PLANT LIST FOR SINGLE FAMILY HOMES SG xx Slow Growing “xx” = minimum height in Small Mature tree height of less than 20 feet at time of planting feet OH Trees adjacent to overhead power lines Medium Mature tree height of between 21 – 40 feet U Trees within Utility Easements Large Mature tree height greater than 41 N Not acceptable for use as a replacement feet * Native Florida Species Varies Mature tree height depends on variety Mature size information based on Betrock’s Florida Landscape Plants Published 2001 GROUP “A” TREES Common Name Botanical Name Uses Mature Tree Size Avocado Persea Americana L Bahama Strongbark Bourreria orata * U, SG 6 S Bald Cypress Taxodium distichum * L Black Olive Shady Bucida buceras ‘Shady Lady’ L Lady Black Olive Bucida buceras L Brazil Beautyleaf Calophyllum brasiliense L Blolly Guapira discolor* M Bridalveil Tree Caesalpinia granadillo M Bulnesia Bulnesia arboria M Cinnecord Acacia choriophylla * U, SG 6 S Group ‘A’ Plant List for Single Family Homes Common Name Botanical Name Uses Mature Tree Size Citrus: Lemon, Citrus spp. OH S (except orange, Lime ect. Grapefruit) Citrus: Grapefruit Citrus paradisi M Trees Copperpod Peltophorum pterocarpum L Fiddlewood Citharexylum fruticosum * U, SG 8 S Floss Silk Tree Chorisia speciosa L Golden – Shower Cassia fistula L Green Buttonwood Conocarpus erectus * L Gumbo Limbo Bursera simaruba * L -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Gumbo Limbo Final Draft.Pub

Stephen H. Brown, Horticulture Agent Bronwyn Mason, Master Gardener Lee County Extension, Fort Myers, Florida (239) 533-7513 [email protected] http://lee.ifas.ufl.edu/hort/GardenHome.shtml Botanical Name: Bursera simaruba Family: Burseraceae Common Names: Gumbo limbo, tourist tree, turpentine tree, almácigo Synonyms (Discarded names): Bursera elaphrium, B. pistacia Origin: South Florida, Bahamas, Carib- bean, Yucatan peninsula, Central America, Northern and Western South America U.S.D.A. Zone: 9B-11 (25°F minimum) Plant Type: Medium to large-sized tree Leaf Type: Pinnately compound Growth Rate: Fast Typical Dimensions: 25’-50’ x 25’-50’ Leaf Persistence: Briefly deciduous Flowering Season: Winter, spring Light Requirements: High Salt Tolerance: High Ft Myers Beach, Florida, late July Drought Tolerance: High Wind Tolerance: High Soil Requirements: Well-drained; wide variety of soil types including alkaline Nutritional Requirements: Low Environmental Problems: Weak branches Major Potential Pests: Croton scale, rugose spiraling whitefly Propagation: Seeds, cuttings Human Hazards: None Uses: Shade, parking lot island, specimen, streetscape, wildlife Natural Geographic Distribution Bursera is a genus of about 100 species in tropical America with gumbo limbo, B. simaruba, being one of the most wide- spread species. It is native along both coasts of Florida southwards from Pinellas County on the west and Brevard County on the east. The species is widespread throughout the Caribbean and the Baha- mas. Its continental range extends from the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico to Panama, Columbia, Venezuela, Guyana, and north- ern Brazil. Ft Myers, Florida Growth and Wood Characteristics Gumbo limbo is one of the fastest growing native trees. The growth is so rapid that a six- to eight-foot tree can be produced from seed in 18 months. -

SFRC T-593 Phenology of Flowering and Fruiting

Report T-593 Phenology of Flowering an Fruiting In Pia t Com unities of Everglades NP and Biscayne N , orida RESOURCE MANAGEMENT EVERGLi\DES NATIONAL PARK BOX 279 NOMESTEAD, FLORIDA 33030 Everglades National Park, South Florida Research Center, P.O. Box 279, Homestead, Florida 33030 PHENOLOGY OF FLOWERING AND FRUITING IN PLANT COMMUNITIES OF EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK AND BISCAYNE NATIONAL MONUMENT, FLORIDA Report T - 593 Lloyd L. Loope U.S. National P ark Service South Florida Research Center Everglades National Park Homestead, Florida 33030 June 1980 Loope, Lloyd L. 1980. Phenology of Flowering and Fruiting in Plant Communities of Everglades National Park and Biscayne National Monument, Florida. South Florida Research Center Report T - 593. 50 pp. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES • ii LIST OF FIGU RES iv INTRODUCTION • 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. • 1 METHODS. • • • • • • • 1 CLIMATE AND WATER LEVELS FOR 1978 •• . 3 RESULTS ••• 3 DISCUSSION. 3 The need and mechanisms for synchronization of reproductive activity . 3 Tropical hardwood forest. • • 5 Freshwater wetlands 5 Mangrove vegetation 6 Successional vegetation on abandoned farmland. • 6 Miami Rock Ridge pineland. 7 SUMMARY ••••• 7 LITERATURE CITED 8 i LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Climatic data for Homestead Experiment Station, 1978 . • . • . • . • . • . • . 10 Table 2. Climatic data for Tamiami Trail at 40-Mile Bend, 1978 11 Table 3. Climatic data for Flamingo, 1978. • • • • • • • • • 12 Table 4. Flowering and fruiting phenology, tropical hardwood hammock, area of Elliott Key Marina, Biscayne National Monument, 1978 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 14 Table 5. Flowering and fruiting phenology, tropical hardwood hammock, Bear Lake Trail, Everglades National Park (ENP), 1978 • . • . • . 17 Table 6. Flowering and fruiting phenology, tropical hardwood hammock, Mahogany Hammock, ENP, 1978. -

Population Density of Cebus Imitator, Honduras

Neotropical Primates 26(1), September 2020 47 POPULATION DENSITY ESTIMATE FOR THE WHITE-FACED CAPUCHIN MONKEY (CEBUS IMITATOR) IN THE MULTIPLE USE AREA MONTAÑA LA BOTIJA, CHOLUTECA, HONDURAS, AND A RANGE EXTENSION FOR THE SPECIES Eduardo José Pinel Ramos M.Sc. Biological Sciences, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras, Cra. 27 a # 67-14, barrio 7 de agosto, Bogotá D.C., e-mail: <[email protected]> Abstract Honduras is one of the Neotropical countries with the least amount of information available regarding the conservation status of its wild primate species. Understanding the real conservation status of these species is relevant, since they are of great importance for ecosystem dynamics due to the diverse ecological services they provide. However, there are many threats that endanger the conservation of these species in the country such as deforestation, illegal hunting, and illegal wild- life trafficking. The present research is the first official registration of the Central American white-faced capuchin monkey (Cebus imitator) for the Pacific slope in southern Honduras, increasing the range of its known distribution in the country. A preliminary population density estimate of the capuchin monkey was performed in the Multiple Use Area Montaña La Botija using the line transect method, resulting in a population density of 1.04 groups/km² and 4.96 ind/km² in the studied area. These results provide us with a first look at an isolated primate population that has never been described before and demonstrate the need to develop long-term studies to better understand the population dynamics, ecology, and behaviour, for this group in the zone. -

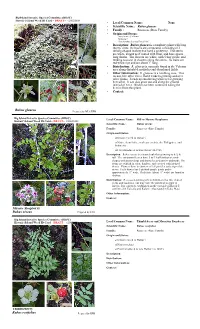

Mysore Raspberry Rubus Niveus Thimbleberry Rubus Rosifolius

Big Island Invasive Species Committee (BIISC) Hawaii‘i Island Weed ID Card – DRAFT– v20030508 • Local/Common Name: None • Scientific Name: Rubus glaucus • Family : Rosaceae (Rose Family) • Origin and Status: – Invasive weed in Hawai‘i – Native to ? – First introduced to into Hawai‘i in ? • Description: Rubus glaucus is a raspberry plant with long thorny vines. Its leaves are compound, consisting of 3 oblong-shaped leaflets that have a pointy tip. The stems are white, almost as if coated with flour, and have sparse long thorns. The flowers are white, with 5 tiny petals, and tending to occur in clusters along the stems. Its fruits are red when ripe and are about 1” long. • Distribution: R. glaucus is currently found in the Volcano area along disturbed roadsides and abandoned fields. • Other Information: R. glaucus is a rambling vine. This means, like other vines, that it tends to grow up and over other plants. It ends up smothering whatever is growing beneath it. It can also grow out and along the ground instead of erect. Birds have been witnessed eating the berries from this plant. • Contact: Rubus glaucus Prepared by MLC/KFB Big Island Invasive Species Committee (BIISC) Local/Common Name: Hill or Mysore Raspberry Hawaii‘i Island Weed ID Card – DRAFT– v20030508 Scientific Name: Rubus niveus Family : Rosaceae (Rose Family) Origin and Status: ?Invasive weed in Hawai‘i ?Native from India, southeastern Asia, the Philippines, and Indonesia ?First introduced to into Hawai‘i in 1965 Description: Rubus niveus is a stout shrub that grows up to 6 ½ ft. tall . The compound leaves have 5 to 9 leaflets that are oval- shaped with pointed tips and thorns located on the underside. -

Restoring Southern Florida's Native Plant Heritage

A publication of The Institute for Regional Conservation’s Restoring South Florida’s Native Plant Heritage program Copyright 2002 The Institute for Regional Conservation ISBN Number 0-9704997-0-5 Published by The Institute for Regional Conservation 22601 S.W. 152 Avenue Miami, Florida 33170 www.regionalconservation.org [email protected] Printed by River City Publishing a division of Titan Business Services 6277 Powers Avenue Jacksonville, Florida 32217 Cover photos by George D. Gann: Top: mahogany mistletoe (Phoradendron rubrum), a tropical species that grows only on Key Largo, and one of South Florida’s rarest species. Mahogany poachers and habitat loss in the 1970s brought this species to near extinction in South Florida. Bottom: fuzzywuzzy airplant (Tillandsia pruinosa), a tropical epiphyte that grows in several conservation areas in and around the Big Cypress Swamp. This and other rare epiphytes are threatened by poaching, hydrological change, and exotic pest plant invasions. Funding for Rare Plants of South Florida was provided by The Elizabeth Ordway Dunn Foundation, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and the Steve Arrowsmith Fund. Major funding for the Floristic Inventory of South Florida, the research program upon which this manual is based, was provided by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the Steve Arrowsmith Fund. Nemastylis floridana Small Celestial Lily South Florida Status: Critically imperiled. One occurrence in five conservation areas (Dupuis Reserve, J.W. Corbett Wildlife Management Area, Loxahatchee Slough Natural Area, Royal Palm Beach Pines Natural Area, & Pal-Mar). Taxonomy: Monocotyledon; Iridaceae. Habit: Perennial terrestrial herb. Distribution: Endemic to Florida. Wunderlin (1998) reports it as occasional in Florida from Flagler County south to Broward County. -

Cocoa Beach Maritime Hammock Preserve Management Plan

MANAGEMENT PLAN Cocoa Beach’s Maritime Hammock Preserve City of Cocoa Beach, Florida Florida Communities Trust Project No. 03 – 035 –FF3 Adopted March 18, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………. 1 II. Purpose …………………………………………………………….……. 2 a. Future Uses ………….………………………………….…….…… 2 b. Management Objectives ………………………………………….... 2 c. Major Comprehensive Plan Directives ………………………..….... 2 III. Site Development and Improvement ………………………………… 3 a. Existing Physical Improvements ……….…………………………. 3 b. Proposed Physical Improvements…………………………………… 3 c. Wetland Buffer ………...………….………………………………… 4 d. Acknowledgment Sign …………………………………..………… 4 e. Parking ………………………….………………………………… 5 f. Stormwater Facilities …………….………………………………… 5 g. Hazard Mitigation ………………………………………………… 5 h. Permits ………………………….………………………………… 5 i. Easements, Concessions, and Leases …………………………..… 5 IV. Natural Resources ……………………………………………..……… 6 a. Natural Communities ………………………..……………………. 6 b. Listed Animal Species ………………………….…………….……. 7 c. Listed Plant Species …………………………..…………………... 8 d. Inventory of the Natural Communities ………………..………….... 10 e. Water Quality …………..………………………….…..…………... 10 f. Unique Geological Features ………………………………………. 10 g. Trail Network ………………………………….…..………..……... 10 h. Greenways ………………………………….…..……………..……. 11 i Adopted March 18, 2004 V. Resources Enhancement …………………………..…………………… 11 a. Upland Restoration ………………………..………………………. 11 b. Wetland Restoration ………………………….…………….………. 13 c. Invasive Exotic Plants …………………………..…………………... 13 d. Feral -

Final Rule to List Reticulated Python And

Vol. 80 Tuesday, No. 46 March 10, 2015 Part II Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife 50 CFR Part 16 Injurious Wildlife Species; Listing Three Anaconda Species and One Python Species as Injurious Reptiles; Final Rule VerDate Sep<11>2014 18:14 Mar 09, 2015 Jkt 235001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\10MRR2.SGM 10MRR2 mstockstill on DSK4VPTVN1PROD with RULES2 12702 Federal Register / Vol. 80, No. 46 / Tuesday, March 10, 2015 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Services Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife 3330) to list Burmese (and Indian) Service, 1339 20th Street, Vero Beach, pythons, Northern African pythons, Fish and Wildlife Service FL 32960–3559; telephone 772–562– Southern African pythons, and yellow 3909 ext. 256; facsimile 772–562–4288. anacondas as injurious wildlife under 50 CFR Part 16 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Bob the Lacey Act. The remaining five RIN 1018–AV68 Progulske, Everglades Program species (reticulated python, boa Supervisor, South Florida Ecological constrictor, green anaconda, [Docket No. FWS–R9–FHC–2008–0015; Services Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife DeSchauensee’s anaconda, and Beni FXFR13360900000–145–FF09F14000] Service, 1339 20th Street, Vero Beach, anaconda) were not listed at that time and remained under consideration for Injurious Wildlife Species; Listing FL 32960–3559; telephone 772–469– 4299. If you use a telecommunications listing. With this final rule, we are Three Anaconda Species and One listing four of those species (reticulated Python Species as Injurious Reptiles device for the deaf (TDD), please call the Federal Information Relay Service python, green anaconda, AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, (FIRS) at 800–877–8339. -

Florida Bonneted Bat1 Holly K

WEC381 Florida’s Bats: Florida Bonneted Bat1 Holly K. Ober, Terry J. Doonan, and Emily H. Evans2 The Florida bonneted bat (Figure 1) is one of only two endangered species of bat in Florida, and the state’s only endemic flying mammal (“endemic” means that it is found nowhere in the world but in Florida). With a wingspan of 20 inches (50 cm), it is Florida’s largest bat and the third largest of all 48 species of bats in the United States. Fur color varies from brown to gray to black. Figure 2. Florida bonneted bats can be found in just 10 counties in Figure 1. Florida bonneted bat (Eumops floridanus). southern Florida. Credits: Merlin Tuttle, Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation (http://www. Credits: Emily Evans merlintuttle.com/) These bats roost (sleep during the day) in cavities or Little is known about these rare bats. They occur only in beneath peeling bark of live and dead pine trees (Pinus southern Florida, with recent confirmation of presence in elliotti, P. palustris), bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), Miami-Dade, Broward, Collier, Hendry, Lee, Charlotte, royal palms (Roystonea regia), rock outcrops, bat houses, Glades, Highlands, De Soto, and Polk Counties (Figure 2). chimneys, and under barrel roof tiles. They roost alone or in groups of up to 50 individuals. Florida bonneted bats typically leave their roosts shortly after sunset. They fly long distances to forage on insects at high altitudes. Bonneted bats’ broad, funnel-shaped ears 1. This document is WEC381, one of a series of the Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, UF/IFAS Extension. -

FINAL REPORT PSRA Vegetation Monitoring 2005-2006 PC P502173

Rare Plants and Their Locations at Picayune Strand Restoration Area: Task 4a FINAL REPORT PSRA Vegetation Monitoring 2005-2006 PC P502173 Steven W. Woodmansee and Michael J. Barry [email protected] December 20, 2006 Submitted by The Institute for Regional Conservation 22601 S.W. 152 Avenue, Miami, Florida 33170 George D. Gann, Executive Director Submitted to Mike Duever, Ph.D. Senior Environmental Scientist South Florida Water Management District Fort Myers Service Center 2301 McGregor Blvd. Fort Myers, Florida 33901 Table of Contents Introduction 03 Methods 03 Results and Discussion 05 Acknowledgements 38 Citations 39 Tables: Table 1: Rare plants recorded in the vicinity of the Vegetation Monitoring Transects 05 Table 2: The Vascular Plants of Picayune Strand State Forest 24 Figures: Figure 1: Picayune Strand Restoration Area 04 Figure 2: PSRA Rare Plants: Florida Panther NWR East 13 Figure 3: PSRA Rare Plants: Florida Panther NWR West 14 Figure 4: PSRA Rare Plants: PSSF Northeast 15 Figure 5: PSRA Rare Plants: PSSF Northwest 16 Figure 6: PSRA Rare Plants: FSPSP West 17 Figure 7: PSRA Rare Plants: PSSF Southeast 18 Figure 8: PSRA Rare Plants: PSSF Southwest 19 Figure 9: PSRA Rare Plants: FSPSP East 20 Figure 10: PSRA Rare Plants: TTINWR 21 Cover Photo: Bulbous adder’s tongue (Ophioglossum crotalophoroides), a species newly recorded for Collier County, and ranked as Critically Imperiled in South Florida by The Institute for Regional Conservation taken by the primary author. 2 Introduction The South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) plans on restoring the hydrology at Picayune Strand Restoration Area (PSRA) see Figure 1.