Economics After Neoliberalism: Introducing the Efip Project †

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

Cryptocurrency: the Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues

Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues Updated April 9, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45427 SUMMARY R45427 Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and April 9, 2020 Selected Policy Issues David W. Perkins Cryptocurrencies are digital money in electronic payment systems that generally do not require Specialist in government backing or the involvement of an intermediary, such as a bank. Instead, users of the Macroeconomic Policy system validate payments using certain protocols. Since the 2008 invention of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, cryptocurrencies have proliferated. In recent years, they experienced a rapid increase and subsequent decrease in value. One estimate found that, as of March 2020, there were more than 5,100 different cryptocurrencies worth about $231 billion. Given this rapid growth and volatility, cryptocurrencies have drawn the attention of the public and policymakers. A particularly notable feature of cryptocurrencies is their potential to act as an alternative form of money. Historically, money has either had intrinsic value or derived value from government decree. Using money electronically generally has involved using the private ledgers and systems of at least one trusted intermediary. Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, generally employ user agreement, a network of users, and cryptographic protocols to achieve valid transfers of value. Cryptocurrency users typically use a pseudonymous address to identify each other and a passcode or private key to make changes to a public ledger in order to transfer value between accounts. Other computers in the network validate these transfers. Through this use of blockchain technology, cryptocurrency systems protect their public ledgers of accounts against manipulation, so that users can only send cryptocurrency to which they have access, thus allowing users to make valid transfers without a centralized, trusted intermediary. -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

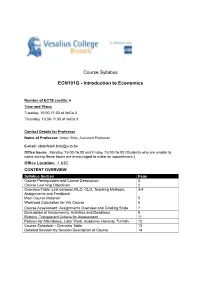

Course Syllabus ECN101G

Course Syllabus ECN101G - Introduction to Economics Number of ECTS credits: 6 Time and Place: Tuesday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Thursday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Contact Details for Professor Name of Professor: Abdel. Bitat, Assistant Professor E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Monday, 15:00-16:00 and Friday, 15:00-16:00 (Students who are unable to come during these hours are encouraged to make an appointment.) Office Location: -1.63C CONTENT OVERVIEW Syllabus Section Page Course Prerequisites and Course Description 2 Course Learning Objectives 2 Overview Table: Link between MLO, CLO, Teaching Methods, 3-4 Assignments and Feedback Main Course Material 5 Workload Calculation for this Course 6 Course Assessment: Assignments Overview and Grading Scale 7 Description of Assignments, Activities and Deadlines 8 Rubrics: Transparent Criteria for Assessment 11 Policies for Attendance, Later Work, Academic Honesty, Turnitin 12 Course Schedule – Overview Table 13 Detailed Session-by-Session Description of Course 14 Course Prerequisites (if any) There are no pre-requisites for the course. However, since economics is mathematically intensive, it is worth reviewing secondary school mathematics for a good mastering of the course. A great source which starts with the basics and is available at the VUB library is Simon, C., & Blume, L. (1994). Mathematics for economists. New York: Norton. Course Description The course illustrates the way in which economists view the world. You will learn about basic tools of micro- and macroeconomic analysis and, by applying them, you will understand the behavior of households, firms and government. Problems include: trade and specialization; the operation of markets; industrial structure and economic welfare; the determination of aggregate output and price level; fiscal and monetary policy and foreign exchange rates. -

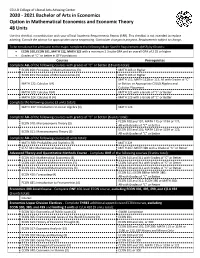

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme Subject Brief Individuals and Societies: Economics—Higher Level First Assessments 2022—Last Assessments 2029

International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme Subject Brief Individuals and societies: Economics—higher level First assessments 2022—last assessments 2029 The Diploma Programme (DP) is a rigorous pre-university course of study designed for students in the 16 to 19 age range. It is a broad-based two-year course that aims to encourage students to be knowledgeable and inquiring, but also caring and compassionate. There is a strong emphasis on encouraging students MA PROG PLO RAM to develop intercultural understanding, open-mindedness, and the attitudes necessary for DI M IB S IN LANG E UDIE UAG ST LITERAT E them to respect and evaluate a range of points of view. AND URE A IN The course is presented as six academic areas enclosing a central core. Students study E E N D N DG G E D IV A O L E I W X S ID U IT O T O two modern languages (or a modern language and a classical language), a humanities G E U IS N N C N K ES TO T I A U CH EA D E A F A C L O H E T or social science subject, an experimental science, mathematics and one of the creative L Q R S O I I C P N D P G E A Y S A E R arts. Instead of an arts subject, students can choose two subjects from another area. S O S E A Y H It is this comprehensive range of subjects that makes the Diploma Programme a T demanding course of study designed to prepare students effectively for university A P G entrance. -

THE NEOLIBERAL THEORY of SOCIETY Simon Clarke

THE NEOLIBERAL THEORY OF SOCIETY Simon Clarke The ideological foundations of neo-liberalism Neoliberalism presents itself as a doctrine based on the inexorable truths of modern economics. However, despite its scientific trappings, modern economics is not a scientific discipline but the rigorous elaboration of a very specific social theory, which has become so deeply embedded in western thought as to have established itself as no more than common sense, despite the fact that its fundamental assumptions are patently absurd. The foundations of modern economics, and of the ideology of neoliberalism, go back to Adam Smith and his great work, The Wealth of Nations. Over the past two centuries Smith’s arguments have been formalised and developed with greater analytical rigour, but the fundamental assumptions underpinning neoliberalism remain those proposed by Adam Smith. Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations as a critique of the corrupt and self-aggrandising mercantilist state, which drew its revenues from taxing trade and licensing monopolies, which it sought to protect by maintaining an expensive military apparatus and waging costly wars. The theories which supported the state conceived of exchange as a ‘zero-sum game’, in which one party’s gain was the other party’s loss, so the maximum benefit from exchange was to be extracted by force and fraud. The fundamental idea of Smith’s critique was that the ‘wealth of the nation’ derived not from the accumulation of wealth by the state, at the expense of its citizens and foreign powers, but from the development of the division of labour. The division of labour developed as a result of the initiative and enterprise of private individuals and would develop the more rapidly the more such individuals were free to apply their enterprise and initiative and to reap the corresponding rewards. -

Mathematical Economics

ECONOMICS 113: Mathematical Economics Fall 2016 Basic information Lectures Tu/Th 14:00-15:20 PCYNH 120 Instructor Prof. Alexis Akira Toda Office hours Tu/Th 13:00-14:00, ECON 211 Email [email protected] Webpage https://sites.google.com/site/aatoda111/ (Go to Teaching ! Mathematical Economics) TA Miles Berg, Econ 128, [email protected] (Office hours: TBD) Course description Carl Friedrich Gauss said mathematics is the queen of the sciences (and number theory is the queen of mathematics).1 Paul Samuelson said economics is the queen of the social sciences.2 Not surprisingly, modern economics is a highly mathematical subject. Mathematical economics studies the mathematical foundations of economic theory in the approach known as the Arrow-Debreu model of general equilibrium. Partial equilibrium (things like demand and supply curves), which you have probably learned in Econ 100ABC, considers each market separately. General equilibrium (GE for short), on the other hand, considers the economy as a whole, taking into account the interaction of all markets. Econ 113 is probably the most mathematically advanced undergraduate course of- fered at UCSD Economics, but it should have a high return. In the course, we will develop a mathematical model of classical economic thoughts like Bentham's \greatest happiness principle" and Smith's \invisible hand", and prove theorems. Then we will apply the theory to international trade, finance, social security, etc. Time permitting, I will talk about my own research. Prerequisites A year of calculus and a year of upper division microeconomic theory (at UCSD these courses are Math 20ABC and Economics 100ABC) are required. -

450601 Economics

Kentucky Department of Education - Course Standards Course Standards Course Code: 450601 Course Name: Economics Grade Level: 9-12 Upon course completion students should be able to: Standards Big Idea: Economics Economics includes the study of production, distribution and consumption of goods and services. Students need to understand how their economic decisions affect them, others, the nation and the world. The purpose of economic education is to enable individuals to function effectively both in their own personal lives and as citizens and participants in an increasingly connected world economy. Students need to understand the benefits and costs of economic interaction and interdependence among people, societies, and governments. Academic Expectations 2.18 Students understand economic principles and are able to make economic decisions that have consequences in daily living. High School Enduring Knowledge – Understandings Students will understand that: ▪ the basic economic problem confronting individuals, societies and governments is scarcity; as a result of scarcity, economic choices and decisions must be made. ▪ economic systems are created by individuals, societies and governments to achieve broad goals (e.g., security, growth, freedom, efficiency, equity). ▪ markets (e.g., local, national, global) are institutional arrangements that enable buyers and sellers to exchange goods and services. ▪ all societies deal with questions about production, distribution and consumption. ▪ a variety of fundamental economic concepts (e.g., supply and demand, opportunity cost) affect individuals, societies and governments. ▪ our global economy provides for a level of interdependence among individuals, societies and governments of the world. ▪ the United States Government and its policies play a major role in the performance of the U.S. -

JA Economics® Course Overview and Outline

JA Economics® | Course Overview and Outline Initial JA Economics® Course Release Overview and Outline Spring 2019 Market for Goods JA Economics is a one-semester course that connects high and Services school students to the economic principles that influence their daily lives as well as their futures. It addresses each BANK of the economics standards identified by the Council for Production of Goods and Household Economic Education as being essential to complete a high Services + + Consumer school economics course. Course components equip students to: Market for Labor • Learn the necessary concepts applicable to state and national educational standards • Apply economic reasoning and skills in the world around them • Synthesize elective concepts through a cumulative, tangible deliverable (optional case studies and/or projects) • Demonstrate the skills necessary for future financial literacy pathway success • Integrate College and Career Readiness anchor standards in Reading, Informational Text, Speaking and Listening, and Vocabulary Volunteers engage with students through a variety of activities that includes subject matter guest speaking and coaching or advising for case study and project course work. Volunteer activities help students better understand the relationship between what they learn in school, their future career, and their successful participation in today’s global economy. Through a variety of experiential activities presented by the teacher and volunteer, students better understand the relationship between what they learn -

Course Outline Economics 100 Introduction to Microeconomics

Division of Applied Science & Management School of Management, Tourism & Hospitality Semester 2015-01, Fall 2015 Course Outline Economics 100 Introduction to Microeconomics 45.0 Hours 3.0 Credits Prepared by _____________________________ Date: August 18, 2015 Brian Paul, Instructor Approved by _____________________________ Date: _______________ Margaret Dumkee, Dean, Applied Science & Management YUKON COLLEGE Copyright August 2015 All rights are reserved. None of the material covered by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means - electronic or mechanical - or traded, rented or resold without written permission from Yukon College. This course outline was prepared by Brian Paul on August 18, 2015. Yukon College 500 College Drive Post Office Box 2799 Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 5K4 Division of Applied Science & Management School of Management, Tourism & Hospitality Economics 100 Semester 2015-01, Fall 2015 Introduction to Microeconomics Instructor: Brian Paul, M.Sc., MBA Office Location: Room #A 2412 - Ayamdigut Campus Office Hours: 09:00 - 12:00, Monday 13:00 - 14:30, Tuesday and Thursday 09:00 - 12:00 & 13:00 - 16:00, Wednesday 13:00 - 16:00, Friday (or by appointment) Telephone Numbers: 668-8756 (Ayamdigut) 667-6763 (Home) 668-8890 (FAX - Ayamdigut) E-Mail: [email protected] (Ayamdigut) [email protected] (Home) Course Length: 45.0 hours (1.5 hrs/day; 2 days/week; 15 weeks) Course Days: Tue / Fri Course Time: 10:30 - 12:00 Class Room #: A 2206 Lab Room #: Not Applicable Course Description: Introduction to Microeconomics is an introductory level course covering the principles of production and consumption - and the exchange of goods and services - in a market economy. -

The Integration of Economic History Into Economics

Cliometrica https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-018-0170-8 ORIGINAL PAPER The integration of economic history into economics Robert A. Margo1 Received: 28 June 2017 / Accepted: 16 January 2018 Ó Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract In the USA today the academic field of economic history is much closer to economics than it is to history in terms of professional behavior, a stylized fact that I call the ‘‘integration of economic history into economics.’’ I document this using two types of evidence—use of econometric language in articles appearing in academic journals of economic history and economics; and publication histories of successive cohorts of Ph.D.s in the first decade since receiving the doctorate. Over time, economic history became more like economics in its use of econometrics and in the likelihood of scholars publishing in economics, as opposed to, say, economic history journals. But the pace of change was slower in economic history than in labor economics, another subfield of economics that underwent profound intellec- tual change in the 1950s and 1960s, and there was also a structural break evident for post-2000 Ph.D. cohorts. To account for these features of the data, I sketch a simple, overlapping generations model of the academic labor market in which junior scholars have to convince senior scholars of the merits of their work in order to gain tenure. I argue that the early cliometricians—most notably, Robert Fogel and Douglass North—conceived of a scholarly identity for economic history that kept the field distinct from economics proper in various ways, until after 2000 when their influence had waned.