Learning in the Household∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Does Behavioural Economics Really Matter?

When does behavioural economics really matter? Ian McAuley, University of Canberra and Centre for Policy Development (www.cpd.org.au) Paper to accompany presentation to Behavioural Economics stream at Australian Economic Forum, August 2010. Summary Behavioural economics integrates the formal study of psychology, including social psychology, into economics. Its empirical base helps policy makers in understanding how economic actors behave in response to incentives in market transactions and in response to policy interventions. This paper commences with a short description of how behavioural economics fits into the general discipline of economics. The next section outlines the development of behavioural economics, including its development from considerations of individual psychology into the fields of neurology, social psychology and anthropology. It covers developments in general terms; there are excellent and by now well-known detailed descriptions of the specific findings of behavioural economics. The final section examines seven contemporary public policy issues with suggestions on how behavioural economics may help develop sound policy. In some cases Australian policy advisers are already using the findings of behavioural economics to advantage. It matters most of the time In public policy there is nothing novel about behavioural economics, but for a long time it has tended to be ignored in formal texts. Like Molière’s Monsieur Jourdain who was surprised to find he had been speaking prose all his life, economists have long been guided by implicit knowledge of behavioural economics, particularly in macroeconomics. Keynes, for example, understood perfectly the “money illusion” – people’s tendency to think of money in nominal rather than real terms – in his solution to unemployment. -

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

PAPM 1000 Winter 2011 1

PAPM 1000 Winter 2011 1 Carleton University Arthur Kroeger College of Public Affairs PAPM 1000: Introduction to Public Affairs and Policy Management Winter Term: History of Economic Thought Winter 2011 Instructor: Derek Ireland Wednesday: 14:35-16:25 (2:35-4:25 PM) Office: D199 Loeb Building C164 Loeb Building Phone: 613 747 9593 Office Hours: Wednesdays From 13:00 to 14:20 --Or Email: [email protected] Determined Through Emails with Student Course Objective The objective of the course is to provide an understanding of economic ideas and thinking, how these ideas have evolved and developed and been applied through many centuries, and the implications of economic ideas for past and current policy debates, analysis, development and management. What do we mean by economic ideas? Economic ideas are essentially the concepts, hypotheses, presumptions, guesses and initial thoughts on cause and effect relationships that have been identified, discussed and argued about by economic thinkers over the past decades and centuries. Some of these concepts, guesses and so on are then developed into economic theories which are applied and tested in theoretical and empirical research and policy analysis in our attempts to find answers to such questions as: . Why do consumers purchase what they do? . Why do businesses produce what they do and locate in one place rather than another? . Why do countries trade with each other and should there be more or less international trade in the future? . Why do some countries grow faster than others? . Why are the more advanced OECD countries expected by many economists to grow much more slowly in the future? . -

Cryptocurrency: the Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues

Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues Updated April 9, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45427 SUMMARY R45427 Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and April 9, 2020 Selected Policy Issues David W. Perkins Cryptocurrencies are digital money in electronic payment systems that generally do not require Specialist in government backing or the involvement of an intermediary, such as a bank. Instead, users of the Macroeconomic Policy system validate payments using certain protocols. Since the 2008 invention of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, cryptocurrencies have proliferated. In recent years, they experienced a rapid increase and subsequent decrease in value. One estimate found that, as of March 2020, there were more than 5,100 different cryptocurrencies worth about $231 billion. Given this rapid growth and volatility, cryptocurrencies have drawn the attention of the public and policymakers. A particularly notable feature of cryptocurrencies is their potential to act as an alternative form of money. Historically, money has either had intrinsic value or derived value from government decree. Using money electronically generally has involved using the private ledgers and systems of at least one trusted intermediary. Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, generally employ user agreement, a network of users, and cryptographic protocols to achieve valid transfers of value. Cryptocurrency users typically use a pseudonymous address to identify each other and a passcode or private key to make changes to a public ledger in order to transfer value between accounts. Other computers in the network validate these transfers. Through this use of blockchain technology, cryptocurrency systems protect their public ledgers of accounts against manipulation, so that users can only send cryptocurrency to which they have access, thus allowing users to make valid transfers without a centralized, trusted intermediary. -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

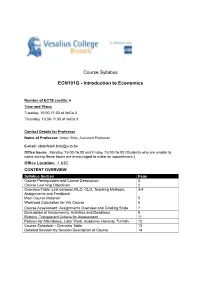

Course Syllabus ECN101G

Course Syllabus ECN101G - Introduction to Economics Number of ECTS credits: 6 Time and Place: Tuesday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Thursday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Contact Details for Professor Name of Professor: Abdel. Bitat, Assistant Professor E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Monday, 15:00-16:00 and Friday, 15:00-16:00 (Students who are unable to come during these hours are encouraged to make an appointment.) Office Location: -1.63C CONTENT OVERVIEW Syllabus Section Page Course Prerequisites and Course Description 2 Course Learning Objectives 2 Overview Table: Link between MLO, CLO, Teaching Methods, 3-4 Assignments and Feedback Main Course Material 5 Workload Calculation for this Course 6 Course Assessment: Assignments Overview and Grading Scale 7 Description of Assignments, Activities and Deadlines 8 Rubrics: Transparent Criteria for Assessment 11 Policies for Attendance, Later Work, Academic Honesty, Turnitin 12 Course Schedule – Overview Table 13 Detailed Session-by-Session Description of Course 14 Course Prerequisites (if any) There are no pre-requisites for the course. However, since economics is mathematically intensive, it is worth reviewing secondary school mathematics for a good mastering of the course. A great source which starts with the basics and is available at the VUB library is Simon, C., & Blume, L. (1994). Mathematics for economists. New York: Norton. Course Description The course illustrates the way in which economists view the world. You will learn about basic tools of micro- and macroeconomic analysis and, by applying them, you will understand the behavior of households, firms and government. Problems include: trade and specialization; the operation of markets; industrial structure and economic welfare; the determination of aggregate output and price level; fiscal and monetary policy and foreign exchange rates. -

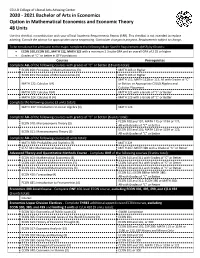

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme Subject Brief Individuals and Societies: Economics—Higher Level First Assessments 2022—Last Assessments 2029

International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme Subject Brief Individuals and societies: Economics—higher level First assessments 2022—last assessments 2029 The Diploma Programme (DP) is a rigorous pre-university course of study designed for students in the 16 to 19 age range. It is a broad-based two-year course that aims to encourage students to be knowledgeable and inquiring, but also caring and compassionate. There is a strong emphasis on encouraging students MA PROG PLO RAM to develop intercultural understanding, open-mindedness, and the attitudes necessary for DI M IB S IN LANG E UDIE UAG ST LITERAT E them to respect and evaluate a range of points of view. AND URE A IN The course is presented as six academic areas enclosing a central core. Students study E E N D N DG G E D IV A O L E I W X S ID U IT O T O two modern languages (or a modern language and a classical language), a humanities G E U IS N N C N K ES TO T I A U CH EA D E A F A C L O H E T or social science subject, an experimental science, mathematics and one of the creative L Q R S O I I C P N D P G E A Y S A E R arts. Instead of an arts subject, students can choose two subjects from another area. S O S E A Y H It is this comprehensive range of subjects that makes the Diploma Programme a T demanding course of study designed to prepare students effectively for university A P G entrance. -

Tying Odysseus to the Mast: Evidence from a Commitment Savings Product in the Philippines*

TYING ODYSSEUS TO THE MAST: EVIDENCE FROM A COMMITMENT SAVINGS PRODUCT IN THE PHILIPPINES* NAVA ASHRAF DEAN KARLAN WESLEY YIN We designed a commitment savings product for a Philippine bank and im- plemented it using a randomized control methodology. The savings product was intended for individuals who want to commit now to restrict access to their savings, and who were sophisticated enough to engage in such a mechanism. We conducted a baseline survey on 1777 existing or former clients of a bank. One month later, we offered the commitment product to a randomly chosen subset of 710 clients; 202 (28.4 percent) accepted the offer and opened the account. In the baseline survey, we asked hypothetical time discounting questions. Women who exhibited a lower discount rate for future relative to current trade-offs, and hence potentially have a preference for commitment, were indeed significantly more likely to open the commitment savings account. After twelve months, average savings balances increased by 81 percentage points for those clients assigned to the treatment group relative to those assigned to the control group. We conclude that the savings response represents a lasting change in savings, and not merely a short-term response to a new product. I. INTRODUCTION Although much has been written, little has been resolved concerning the representation of preferences for consumption over time. Beginning with Strotz [1955] and Phelps and Pollak [1968], models have been put forth that predict individuals will exhibit more impatience for near-term trade-offs than for future trade-offs. These models often incorporate hyperbolic or quasi- * We thank Chona Echavez for collaborating on the field work, the Green Bank of Caraga for cooperation throughout this experiment, John Owens and the USAID/Philippines Microenterprise Access to Banking Services Program team for helping to get the project started, Nathalie Gons, Tomoko Harigaya, Karen Lyons and Lauren Smith for excellent research and field assistance, and three anony- mous referees and the editors. -

THE NEOLIBERAL THEORY of SOCIETY Simon Clarke

THE NEOLIBERAL THEORY OF SOCIETY Simon Clarke The ideological foundations of neo-liberalism Neoliberalism presents itself as a doctrine based on the inexorable truths of modern economics. However, despite its scientific trappings, modern economics is not a scientific discipline but the rigorous elaboration of a very specific social theory, which has become so deeply embedded in western thought as to have established itself as no more than common sense, despite the fact that its fundamental assumptions are patently absurd. The foundations of modern economics, and of the ideology of neoliberalism, go back to Adam Smith and his great work, The Wealth of Nations. Over the past two centuries Smith’s arguments have been formalised and developed with greater analytical rigour, but the fundamental assumptions underpinning neoliberalism remain those proposed by Adam Smith. Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations as a critique of the corrupt and self-aggrandising mercantilist state, which drew its revenues from taxing trade and licensing monopolies, which it sought to protect by maintaining an expensive military apparatus and waging costly wars. The theories which supported the state conceived of exchange as a ‘zero-sum game’, in which one party’s gain was the other party’s loss, so the maximum benefit from exchange was to be extracted by force and fraud. The fundamental idea of Smith’s critique was that the ‘wealth of the nation’ derived not from the accumulation of wealth by the state, at the expense of its citizens and foreign powers, but from the development of the division of labour. The division of labour developed as a result of the initiative and enterprise of private individuals and would develop the more rapidly the more such individuals were free to apply their enterprise and initiative and to reap the corresponding rewards. -

Mathematical Economics

ECONOMICS 113: Mathematical Economics Fall 2016 Basic information Lectures Tu/Th 14:00-15:20 PCYNH 120 Instructor Prof. Alexis Akira Toda Office hours Tu/Th 13:00-14:00, ECON 211 Email [email protected] Webpage https://sites.google.com/site/aatoda111/ (Go to Teaching ! Mathematical Economics) TA Miles Berg, Econ 128, [email protected] (Office hours: TBD) Course description Carl Friedrich Gauss said mathematics is the queen of the sciences (and number theory is the queen of mathematics).1 Paul Samuelson said economics is the queen of the social sciences.2 Not surprisingly, modern economics is a highly mathematical subject. Mathematical economics studies the mathematical foundations of economic theory in the approach known as the Arrow-Debreu model of general equilibrium. Partial equilibrium (things like demand and supply curves), which you have probably learned in Econ 100ABC, considers each market separately. General equilibrium (GE for short), on the other hand, considers the economy as a whole, taking into account the interaction of all markets. Econ 113 is probably the most mathematically advanced undergraduate course of- fered at UCSD Economics, but it should have a high return. In the course, we will develop a mathematical model of classical economic thoughts like Bentham's \greatest happiness principle" and Smith's \invisible hand", and prove theorems. Then we will apply the theory to international trade, finance, social security, etc. Time permitting, I will talk about my own research. Prerequisites A year of calculus and a year of upper division microeconomic theory (at UCSD these courses are Math 20ABC and Economics 100ABC) are required. -

450601 Economics

Kentucky Department of Education - Course Standards Course Standards Course Code: 450601 Course Name: Economics Grade Level: 9-12 Upon course completion students should be able to: Standards Big Idea: Economics Economics includes the study of production, distribution and consumption of goods and services. Students need to understand how their economic decisions affect them, others, the nation and the world. The purpose of economic education is to enable individuals to function effectively both in their own personal lives and as citizens and participants in an increasingly connected world economy. Students need to understand the benefits and costs of economic interaction and interdependence among people, societies, and governments. Academic Expectations 2.18 Students understand economic principles and are able to make economic decisions that have consequences in daily living. High School Enduring Knowledge – Understandings Students will understand that: ▪ the basic economic problem confronting individuals, societies and governments is scarcity; as a result of scarcity, economic choices and decisions must be made. ▪ economic systems are created by individuals, societies and governments to achieve broad goals (e.g., security, growth, freedom, efficiency, equity). ▪ markets (e.g., local, national, global) are institutional arrangements that enable buyers and sellers to exchange goods and services. ▪ all societies deal with questions about production, distribution and consumption. ▪ a variety of fundamental economic concepts (e.g., supply and demand, opportunity cost) affect individuals, societies and governments. ▪ our global economy provides for a level of interdependence among individuals, societies and governments of the world. ▪ the United States Government and its policies play a major role in the performance of the U.S.