Engineering Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Marketing Services Henning Schoenenberger 09.2011 Code

Code Description English A Science A11007 Science, general A12000 History of Science B Biomedicine B0000X Biomedicine general B11001 Cancer Research B12008 Human Genetics B12010 Gene Expression B12020 Gene Therapy B12030 Gene Function B12040 Cytogenetics B12050 Microarrays B13004 Human Physiology B14000 Immunology B14010 Antibodies B15007 Laboratory Medicine B16003 Medical Microbiology B16010 Vaccine B16020 Drug Resistance B1700X Molecular Medicine B18006 Neurosciences B18010 Neurochemistry B19002 Parasitology B21007 Pharmacology/Toxicology B21010 Pharmaceutical Sciences/Technology B22003 Virology B23000 Forensic Science C Chemistry C00004 Chemistry/Food Science, general C11006 Analytical Chemistry C11010 Mass Spectrometry C11020 Spectroscopy/Spectrometry C11030 Chromatography C12002 Biotechnology C12010 Applied Microbiology C12029 Biochemical Engineering C12037 Genetic Engineering C12040 Microengineering C12050 Electroporation C13009 Computer Applications in Chemistry C14005 Documentation and Information in Chemistry C15001 Food Science C16008 Inorganic Chemistry C17004 Math. Applications in Chemistry C18000 Nutrition C19007 Organic Chemistry C19010 Bioorganic Chemistry C19020 Organometallic Chemistry C19030 Carbohydrate Chemistry C21001 Physical Chemistry C21010 Electrochemistry C22008 Polymer Sciences C23004 Safety in Chemistry, Dangerous Goods C24000 Textile Engineering C25007 Theoretical and Computational Chemistry C26003 Gmelin C27000 Industrial Chemistry/Chemical Engineering C28000 Medicinal Chemistry C29000 Catalysis C31000 Nuclear -

Advances in Energy Forecasting Models Based on Engineering

20 Sep 2004 14:55 AR AR227-EG29-10.tex AR227-EG29-10.SGM LaTeX2e(2002/01/18) P1: GCE 10.1146/annurev.energy.29.062403.102042 Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2004. 29:345–81 doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.29.062403.102042 First published online as a Review in Advance on July 30, 2004 ADVANCES IN ENERGY FORECASTING MODELS ∗ BASED ON ENGINEERING ECONOMICS Ernst Worrell,1 Stephan Ramesohl,2 and Gale Boyd3 1Energy Analysis Department, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California 94720; email: [email protected] 2Energy Division, Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment, Energy, 42103 Wuppertal, Germany; email: [email protected] 3Decision and Information Sciences Division, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois 60439; email: [email protected] KeyWords energy modeling, industry, policy, technology ■ Abstract New energy efficiency policies have been introduced around the world. Historically, most energy models were reasonably equipped to assess the impact of classical policies, such as a subsidy or change in taxation. However, these tools are often insufficient to assess the impact of alternative policy instruments. We evalu- ate the so-called engineering economic models used to assess future industrial en- ergy use. Engineering economic models include the level of detail commonly needed to model the new types of policies considered. We explore approaches to improve the realism and policy relevance of engineering economic modeling frameworks. We also explore solutions to strengthen the policy usefulness of engineering eco- nomic analysis that can be built from a framework of multidisciplinary coopera- tion. The review discusses the main modeling approaches currently used and eval- uates the weaknesses in current models. -

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

Engineering Economy for Economists

AC 2008-2866: ENGINEERING ECONOMY FOR ECONOMISTS Peter Boerger, Engineering Economic Associates, LLC Peter Boerger is an independent consultant specializing in solving problems that incorporate both technological and economic aspects. He has worked and published for over 20 years on the interface between engineering, economics and public policy. His education began with an undergraduate degree in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, adding a Master of Science degree in a program of Technology and Public Policy from Purdue University and a Ph.D. in Engineering Economics from the School of Industrial Engineering at Purdue University. His firm, Engineering Economic Associates, is located in Indianapolis, IN. Page 13.503.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2008 Engineering Economy for Economists 1. Abstract The purpose of engineering economics is generally accepted to be helping engineers (and others) to make decisions regarding capital investment decisions. A less recognized but potentially fruitful purpose is to help economists better understand the workings of the economy by providing an engineering (as opposed to econometric) view of the underlying workings of the economy. This paper provides a review of some literature related to this topic and some thoughts on moving forward in this area. 2. Introduction Engineering economy is inherently an interdisciplinary field, sitting, as the name implies, between engineering and some aspect of economics. One has only to look at the range of academic departments represented by contributors to The Engineering Economist to see the many fields with which engineering economy already relates. As with other interdisciplinary fields, engineering economy has the promise of huge advancements and the risk of not having a well-defined “home base”—the risk of losing resources during hard times in competition with other academic departments/specialties within the same department. -

Cryptocurrency: the Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues

Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues Updated April 9, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45427 SUMMARY R45427 Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and April 9, 2020 Selected Policy Issues David W. Perkins Cryptocurrencies are digital money in electronic payment systems that generally do not require Specialist in government backing or the involvement of an intermediary, such as a bank. Instead, users of the Macroeconomic Policy system validate payments using certain protocols. Since the 2008 invention of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, cryptocurrencies have proliferated. In recent years, they experienced a rapid increase and subsequent decrease in value. One estimate found that, as of March 2020, there were more than 5,100 different cryptocurrencies worth about $231 billion. Given this rapid growth and volatility, cryptocurrencies have drawn the attention of the public and policymakers. A particularly notable feature of cryptocurrencies is their potential to act as an alternative form of money. Historically, money has either had intrinsic value or derived value from government decree. Using money electronically generally has involved using the private ledgers and systems of at least one trusted intermediary. Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, generally employ user agreement, a network of users, and cryptographic protocols to achieve valid transfers of value. Cryptocurrency users typically use a pseudonymous address to identify each other and a passcode or private key to make changes to a public ledger in order to transfer value between accounts. Other computers in the network validate these transfers. Through this use of blockchain technology, cryptocurrency systems protect their public ledgers of accounts against manipulation, so that users can only send cryptocurrency to which they have access, thus allowing users to make valid transfers without a centralized, trusted intermediary. -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

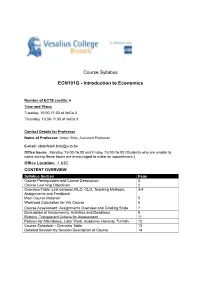

Course Syllabus ECN101G

Course Syllabus ECN101G - Introduction to Economics Number of ECTS credits: 6 Time and Place: Tuesday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Thursday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Contact Details for Professor Name of Professor: Abdel. Bitat, Assistant Professor E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Monday, 15:00-16:00 and Friday, 15:00-16:00 (Students who are unable to come during these hours are encouraged to make an appointment.) Office Location: -1.63C CONTENT OVERVIEW Syllabus Section Page Course Prerequisites and Course Description 2 Course Learning Objectives 2 Overview Table: Link between MLO, CLO, Teaching Methods, 3-4 Assignments and Feedback Main Course Material 5 Workload Calculation for this Course 6 Course Assessment: Assignments Overview and Grading Scale 7 Description of Assignments, Activities and Deadlines 8 Rubrics: Transparent Criteria for Assessment 11 Policies for Attendance, Later Work, Academic Honesty, Turnitin 12 Course Schedule – Overview Table 13 Detailed Session-by-Session Description of Course 14 Course Prerequisites (if any) There are no pre-requisites for the course. However, since economics is mathematically intensive, it is worth reviewing secondary school mathematics for a good mastering of the course. A great source which starts with the basics and is available at the VUB library is Simon, C., & Blume, L. (1994). Mathematics for economists. New York: Norton. Course Description The course illustrates the way in which economists view the world. You will learn about basic tools of micro- and macroeconomic analysis and, by applying them, you will understand the behavior of households, firms and government. Problems include: trade and specialization; the operation of markets; industrial structure and economic welfare; the determination of aggregate output and price level; fiscal and monetary policy and foreign exchange rates. -

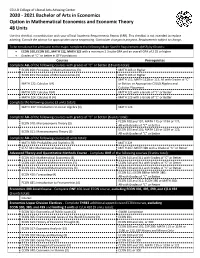

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme Subject Brief Individuals and Societies: Economics—Higher Level First Assessments 2022—Last Assessments 2029

International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme Subject Brief Individuals and societies: Economics—higher level First assessments 2022—last assessments 2029 The Diploma Programme (DP) is a rigorous pre-university course of study designed for students in the 16 to 19 age range. It is a broad-based two-year course that aims to encourage students to be knowledgeable and inquiring, but also caring and compassionate. There is a strong emphasis on encouraging students MA PROG PLO RAM to develop intercultural understanding, open-mindedness, and the attitudes necessary for DI M IB S IN LANG E UDIE UAG ST LITERAT E them to respect and evaluate a range of points of view. AND URE A IN The course is presented as six academic areas enclosing a central core. Students study E E N D N DG G E D IV A O L E I W X S ID U IT O T O two modern languages (or a modern language and a classical language), a humanities G E U IS N N C N K ES TO T I A U CH EA D E A F A C L O H E T or social science subject, an experimental science, mathematics and one of the creative L Q R S O I I C P N D P G E A Y S A E R arts. Instead of an arts subject, students can choose two subjects from another area. S O S E A Y H It is this comprehensive range of subjects that makes the Diploma Programme a T demanding course of study designed to prepare students effectively for university A P G entrance. -

THE NEOLIBERAL THEORY of SOCIETY Simon Clarke

THE NEOLIBERAL THEORY OF SOCIETY Simon Clarke The ideological foundations of neo-liberalism Neoliberalism presents itself as a doctrine based on the inexorable truths of modern economics. However, despite its scientific trappings, modern economics is not a scientific discipline but the rigorous elaboration of a very specific social theory, which has become so deeply embedded in western thought as to have established itself as no more than common sense, despite the fact that its fundamental assumptions are patently absurd. The foundations of modern economics, and of the ideology of neoliberalism, go back to Adam Smith and his great work, The Wealth of Nations. Over the past two centuries Smith’s arguments have been formalised and developed with greater analytical rigour, but the fundamental assumptions underpinning neoliberalism remain those proposed by Adam Smith. Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations as a critique of the corrupt and self-aggrandising mercantilist state, which drew its revenues from taxing trade and licensing monopolies, which it sought to protect by maintaining an expensive military apparatus and waging costly wars. The theories which supported the state conceived of exchange as a ‘zero-sum game’, in which one party’s gain was the other party’s loss, so the maximum benefit from exchange was to be extracted by force and fraud. The fundamental idea of Smith’s critique was that the ‘wealth of the nation’ derived not from the accumulation of wealth by the state, at the expense of its citizens and foreign powers, but from the development of the division of labour. The division of labour developed as a result of the initiative and enterprise of private individuals and would develop the more rapidly the more such individuals were free to apply their enterprise and initiative and to reap the corresponding rewards. -

Engineering Economics for Public Water Utilities

Engineering Economics for Public Water Utilities Max Maurer Eawag: Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology Imprint Author Prof. Dr. Max Maurer, Institute of Environmental Engineering, ETH-Zürich, Switzerland [email protected] Aim This script constitutes part of my lecture ‘Infrastructure Systems in Urban Water Management’ given at ETH Zürich, Switzerland Version 4.7, Jan 2019 License Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) Title photo Wastewater Treatment Plant (Mönchaltorf, ZH) Maurer: Engineering Economics Contents 1. Aim of this script ......................................................................................................................... - 5 - Inflation, Interest & Discount Rate ...................................................................................................... - 7 - 2. The strange concept of money .................................................................................................. - 8 - 3. Inflation........................................................................................................................................ - 8 - 4. Interest rates ............................................................................................................................. - 10 - 5. Discount rate ............................................................................................................................. - 10 - 6. Replacement value .................................................................................................................. -

Economics and Engineering” Pedro Garcia Duarte and Yann Giraud

Introduction: From “Economics as Engineering” to “Economics and Engineering” Pedro Garcia Duarte and Yann Giraud The Transformation of Economics into an Engineering Science: From Analogies to Interactions In recent years, economists, who in the past had mostly insisted on their discipline’s strength as a rigorous social science, have turned to its larger role in transforming society. As early as 2002, Alvin Roth, the Stan- ford-educated economist who received the Nobel memorial prize in 2012, has claimed that members of his community should think of themselves as engineers rather than scientists. By this he meant that they should not be interested solely in the making of theoretical models but also in con- fronting these models with the complexities of real-life situations, which is what engineering is allegedly about. He pointed to the rise of the new sub eld of market design, which he had helped develop, as characteristic of an engineer’s stance and provided several examples of engineering practices applied to economics: the design of labor clearinghouses—such as the entry-level labor market for American physicians—and that of the Federal Communications Commission spectrum auctions (Roth 2002). We want to thank the Center for the History of Political Economy and Duke University Press for their support, as well as the many referees who helped us during the editorial process. Yann Giraud wishes to point out that his research has been supported by the project Labex MME-DII (ANR11–LBX-0023–01). Pedro Duarte acknowledges the nancial support of the Institute for Advanced Studies, at the Université de Cergy-Pontoise, for visiting professorships (2016, 2018) that were critical for the shaping of this joint project.