Art and Phenomenology Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minerva 2014 from the Dean Contents

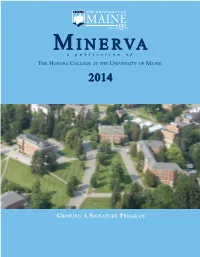

M INERVA a publication of THE HONORS COLLEGE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MAINE 2014 GROWING A SIGNATURE PROGRAM From the Dean ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ ▀ A happy concordance of the calendar has us celebrating the 80th year of Honors at the University of Maine during its sesquicentennial. In this issue François G. Amar, Dean of MINERVA you will see evidence of the huge MINERVA changes since Honors started as a program in 1935, graduating its first cohort of 4 students in 1937. Editors That number has grown steadily over the years and Jennifer Ferguson Nicholas Moore in 2014, 83 students graduated with Honors. 2015 also marks the 13th year since we transitioned from Contributing Writers François G. Amar a Program to a College and are on track to graduate Jennifer Ferguson about 90 students this year, one of the largest classes Melissa Ladenheim in the history of the College. Nicholas Moore Printing The cover of this issue shows another big change: UMaine Printing Services the expansion of the Honors College into part of Estabrooke Hall. Our ‘Honors campus’ within the campus comprises Colvin Hall Readers should send comments to: [email protected] and the Thomson Honors Center in the middle of the photo with Balentine and Estabrooke Halls on the left and right, respectively. We moved the administrative MINERVA is produced annually by the staff of the UMaine Honors College, Thomson center of the College into the northwest corner of Estabrooke (nearest to Charlie’s Honors Center, Colvin Hall and Estabrooke Terrace) in August of 2014. The space also houses offices for the Honors faculty Hall, Orono, ME 04469, 207.581.3263. -

Fractal Expressionism—Where Art Meets Science

Santa Fe Institute. February 14, 2002 9:04 a.m. Taylor page 1 Fractal Expressionism—Where Art Meets Science Richard Taylor 1 INTRODUCTION If the Jackson Pollock story (1912–1956) hadn’t happened, Hollywood would have invented it any way! In a drunken, suicidal state on a stormy night in March 1952, the notorious Abstract Expressionist painter laid down the foundations of his masterpiece Blue Poles: Number 11, 1952 by rolling a large canvas across the oor of his windswept barn and dripping household paint from an old can with a wooden stick. The event represented the climax of a remarkable decade for Pollock, during which he generated a vast body of distinct art work commonly referred to as the “drip and splash” technique. In contrast to the broken lines painted by conventional brush contact with the canvas surface, Pollock poured a constant stream of paint onto his horizontal canvases to produce uniquely contin- uous trajectories. These deceptively simple acts fuelled unprecedented controversy and polarized public opinion around the world. Was this primitive painting style driven by raw genius or was he simply a drunk who mocked artistic traditions? Twenty years later, the Australian government rekindled the controversy by pur- chasing the painting for a spectacular two million (U.S.) dollars. In the history of Western art, only works by Rembrandt, Velazquez, and da Vinci had com- manded more “respect” in the art market. Today, Pollock’s brash and energetic works continue to grab attention, as witnessed by the success of the recent retro- spectives during 1998–1999 (at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and London’s Tate Gallery) where prices of forty million dollars were discussed for Blue Poles: Number 11, 1952. -

Somaesthetics and the Revival of Aesthetics

Filozofski vestnik volume/letnik XXviii • number/Številka 2 • 2007 • 135–149 somaestHetiCs AnD tHe RevivAl oF AestHetiCs Richard shusterman i welcomed Aleš erjavec’s invitation to contribute an article for the interna- tional issue of Filozofski vestnik devoted to “the Revival of Aesthetics” and organized to coincide with the XVII international Congress for Aesthetics (in 2007). it provides me with an excellent occasion to reflect on the role of somaesthetics in the project of reviving aesthetics and promoting a more expansive scope and style of aesthetics, emphasizing international dialogue and transcultural metissage. it is a particularly opportune moment for such reflection, since 2007 marks the tenth anniversary of my first using this term in an english publication.1 Moreover, the international context of this essay is most appropriate since somaesthetics began in international circumstanc- es and was largely inspired through my transcultural explorations in Asian philosophical traditions. As i sit down to write this text on a gray Paris morning, november 2006, i recall that i first introduced the notion of somaesthetics in my German book Vor der Interpretation (1996), where it immediately caught the attention of a reviewer for the influential daily Frankfurter Algemeine Zeitung (12.11.96) who however completely misunderstood (or perhaps intentionally misrepre- sented) its central ideas. With the anti-somatic and exclusively text-centered 1 that was in my Practicing Philosophy: Pragmatism and the Philosophical Life (new York: Routledge, 1997). For further elaboration of somaesthetics, see my Performing Live (ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000), ch. 7–8; “somaesthetics and The Second Sex”, Hypatia 18 (2003), pp. -

3/12/2015 – Press Release

3/12/2015 – Press Release: During COP21, in partnership with the UN, major contemporary artists mobilize and act for Climate Artists 4 Paris Climate 2015 During the 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference / COP 21 of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), major contemporary artists are mobilizing action through art projects displayed in the public spaces of “Greater Paris.” On 9 December at 8pm, a charity auction of 30 works from 14 art projects will be organized by the premier international auction house, Christie’s. The benefits will go to 14 on-the-ground actions both fighting desertification and supporting adaptation to climate change. The initiative is supported by the United Nations Conventions on Climate Change and Desertification. Foundations, companies and NGOs support the implementation of projects in Paris as well as action around the world. 2 steps of the initiative: mobilization then action 1. Mobilization: during COP21, 7 projects will be paired with 7 symbolic locations • Deep breathing / resuscitation for the Reef by Janet Laurence, at the National Museum of Natural History, from 6 October to 14 December • Drowning World by Gideon Mendel, on 10 billboards in the centre of Paris, in the run-up to COP21, from 23 to 29 November • Little Sun by Olafur Eliasson and Frederik Ottensen, march from Clichy-Montfermeil to Bourget, on 2 December • Ice Watch by Olafur Eliasson and Minik Rosing, Place du Panthéon, from 3 to 13 December • Aeroscene by Tomas Saraceno, at the Grand Palais, from 4 to 10 December • Flying Shell, by Pavel Peppertein, and Sky Puzzle by Yin Xiuzhen, at Charles de Gaulle airport, from 8 December to 3 January (dates and location still to be confirmed) • Human Energy by Yann Toma, the Eiffel Tower, from 5t to 12 December 2. -

Weeping Woman, 1937 (Room 3)

Tate Modern Artist and Society Boiler House (North) Level 2 West 11:00-11:45 Laurence Shafe 1 Artist and Society Rachel Whiteread, Demolished, 1996 (Room 1) ....................................................................... 5 Marwan Rechmaoui, Monument for Living, 2001-8 (Room 1) ................................................. 9 Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), Composition B (No.II) with Red, 1935 (Room 2) ........................ 13 Victor Pasmore, Abstract in White, Green, Black, Blue, Red, Grey and Pink, c. 1963 ............. 17 Hélio Oiticica, Metaesquema, 1958 (Room 2) ........................................................................ 21 Pablo Picasso, Weeping Woman, 1937 (Room 3) ................................................................... 25 Salvador Dalí, Autumnal Cannibalism, 1936 (Room 3) ........................................................... 29 André Fougeron, Martyred Spain, 1937 (Room 3) .................................................................. 33 David Alfaro Siqueiros, Cosmos and Disaster, 1936 (Room 3) ................................................ 37 Kaveh Golestan, Untitled (Prostitute series), 1975-77 ........................................................... 41 Lorna Simpson, Five Day Forecast, 1991 (not on display) ....................................................... 44 Joseph Beuys, Lightning with Stag in its Glare, 1958-85 (Room 7) .......................................... 48 Theaster Gates, Civil Tapestry 4, 2011 (Room 9) ................................................................... -

1 Martial POIRSON [email protected]

Martial POIRSON [email protected] Professeur des universités 06 63 71 73 51 Université Paris 8-Vincennes-Saint Denis Né le 06.02.74 Montreuil (93) FORMATION ACADÉMIQUE - 2011 : HDR soutenue à l’Université Paris Ouest-Nanterre-La Défense sous le parrainage de Christian Biet. Sujet : « Politique de la représentation : littérature, arts du spectacle, discours de savoir (XVII-XXIe siècles) ». Jury : Christian Biet (Université Paris Ouest) ; Yves Citton (Université Grenoble 3) ; Pierre Frantz (Université Paris 4-La Sorbonne) ; Christophe Martin (Université Paris Ouest) ; Isabelle Moindrot (Université Paris 8) ; Guy Spielmann (Georgetown University). - 2004 : Doctorat de l’Université Paris 10-Nanterre, sous la direction de Christian Biet. Félicitations du jury à l’unanimité et proposition de publication. Qualification CNU en 9e et 18e sections. Sujet : « Comédie et économie : argent, morale et intérêt dans le théâtre français ». Jury : Christian Biet (Université Paris 10-Nanterre), Pierre Frantz (Université Paris 4-La Sorbonne) ; John Dunkley (Aberdeen University) ; Alain Viala (Oxford University) ; Emmanuel Wallon (Université Paris 10-Nanterre). - 1998 : Agrégation de Sciences économiques et sociales (reçu second). - 1993-1997 : Université Paris 10-Nanterre, cursus Lettres modernes et Arts du spectacle. - 1993-1997 : École Normale Supérieure (Fontenay Saint-Cloud), double formation Lettres et arts / Sciences économiques et sociales. - 1991-1993 : Classe préparatoire au Lycée Henri IV. EXPÉRIENCES PROFESSIONNELLES Expérience universitaire - Depuis 2014 : Professeur de l’Université Paris 8, Département Théâtre, UFR Arts- esthétique-philosophie. - 2012-2014 : Professeur de l’Université Grenoble 3, UFR Lettres et Arts. - 2005-2011 : Maître de conférences de l’Université Grenoble 3, Département Lettres modernes. - 2003-2005 : Enseignant en classes préparatoires aux Écoles Normales Supérieures (Khâgne BL) au lycée Janson de Sailly, en sciences économiques et sociales. -

Official Selection 2013 / 2015 54 Artists from 9 European

Press release 1 Montrouge, July 9th 2013 officiAL SELEcTION 2013 / 2015 54 ARTiSTS FROM 9 EURoPEAN COUNTRiES WILL REPRESENT NEW TRENDS IN EMERGING ART AT THE 2013 / 2015 EDITION OF THE JCE Biennial. The JCE | Jeune Création Européenne Biennial stops in Montrouge From October 17th to November 6th 2013 – Open daily from 12 to 7 p.m. Le Beffroi – 2 place Émile Cresp – 92120 Montrouge Metro Line 4, Mairie de Montrouge station Free admission For this new edition, the JCE | Jeune Création Européenne Biennial continues to promote emerging artists inter- nationally and extends its networks of partners within the European Community. Today, the mayor of Montrouge Mr. Jean-Loup Metton and the executive curator of the JCE Mr. Andrea Ponsini will announce the official selection of 54 artists from 9 European countries. They were selected in each coun- try by the artistic curators of the JCE’s partner institutions. Their work will be exhibited from October 17th to November 6th 2013 at Le Beffroi in Montrouge. In 2000, as an extension of the Salon de Montrouge founded in 1955, the city of Montrouge furthered its commit- ment to “discovering and supporting emerging artists” by setting up a European network in order to encourage partner cities to support their countries’ young artists. This network of partners cities pledges to host a stop of JCE | Jeune Création Européenne Biennial 2013 / 2015 and to supply artists with residency studios for the duration of the Biennial. Each partner country provides the JCE with its expertise in the field of emerging art by naming an artistic curator in charge of singling out new talents. -

Abstract Painting Workshop

Abstract painting workshop Move beyond realism and paint your emotions and ideas “We are all hungry and thirsty for concrete images. Abstract art will have been good for one thing: to restore its exact virginity to figurative art.” Salvador Dali Abstract art became popular in the last century when some artists started to paint shapes in order to create a composition completely detached from the representation of reality. From then on many painters have experimented this non-figurative art (also called non-objective art), which can be found also in other cultures of the past. During this 5-day intensive workshop students will learn to practice different kinds of non- representational art such as geometric abstraction, whose groundwork were laid by Piet Mondrian, lyrical abstraction, which follows the lessons of Wassily Kandinsky, and partial abstraction in which reality is conspicuously and deliberately transformed (Fauvism and Cubism are probably the most famous art mouvements that embodied partial abstraction). Along with this subjects students will be taught to master the different media that can be used for abstract paintings, such as oil, acrylic colors, watercolors or even mixed media. Students will eventually grasp that behind an abstract painting there should always be an idea or a feeling supported by a solid structure or by a centre of interest that students have previously developed by using forms, colors and lines. During this seminar students will realize how hard but also gratifying can be to develop and foster a personal project either on a paper sheet or on a canvas by using their talent and their artistic skils. -

The Sincerest Form of Flattery: Modern Art and the Kimono

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2006 The Sincerest Form of Flattery: Modern Art and the Kimono Valerie Foley [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Foley, Valerie, "The Sincerest Form of Flattery: Modern Art and the Kimono" (2006). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 315. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/315 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Sincerest Form of Flattery: Modern Art and the Kimono Valerie Foley [email protected] In 2003 I enrolled in a master’s degree program in arts administration. In addition to such classes as exhibition planning, appraisals, and computer applications, we had two sweeping modern art surveys, which took us from the birth of impressionism in the 1860s to emerging artists of the 21st century. For one end term project, we each had to design a complete hypothetical exhibition, from mission statement to budget to invitation card to gallery space. The only restriction was that we had to demonstrate on paper that we could actually pull it off. At that time, I had recently seen a kimono in a catalogue from the Honolulu Academy of Arts for an exhibition of early 20th century Japanese art entitled Taisho Chic that had all the characteristics of a work by Miró, one of the artists in the program’s survey.1 Codes et Constellations Dans L'Amour D'Une Femme, dated 19412 is an actual Miró. -

Merleau-Ponty in Contemporary Perspective Phaenomenologica

MERLEAU-PONTY IN CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVE PHAENOMENOLOGICA COLLECTION FONDEE PAR H.L. VAN BREDA ET PUBLIEE SOUS LE PATRONAGE DES CENTRES D'ARCHIVES-HUSSERL 129 MERLEAU-PONTY IN CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVE Edited by PATRICK BURKE and JAN VAN DER VEKEN Comite de redaction de la collection: President: S. IJsseling (Leuven) Membres: W. Marx (Freiburg i. Br.), J.N. Mohanty (Philadelphia), P. Ricreur (Paris), E. Straker (KOln), J. Taminiaux (Louvain-Ia-Neuve), Secretaire: J. Taminiaux MERLEAU-PONTY IN CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVES Edited by PATRICK BURKE and lAN VAN DER VEKEN ..... SPRlNGER-SCIENCE+BUSINESS" MEDIA, B.V. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Merleau-Ponty in contemporary perspective! edited by Patrick Burke and Jan Van der Veken. p. cm. -- IPhaenomenologica ; v. 129) Papers presented at the internatIonal sympasium on Merleau-Ponty. held in Nov. 1991 by the Institute of Philosophy and the Husserl Archives at the Kathol ieke Universiteit te Leuven. rncludes bibl iographical references and index. ISBN 978·94·010-4768·5 ISBN 978·94·011·1751·7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978·94·011·1751·7 1. Merleau-Ponty. Maurice. 1908-1961--Congresses. r. Burke. Patrick. II. Veken. Jan van der. III. Series, Phaenomenologica 129. B2430.M3764M4695 1993 194--dc20 92-38343 ISBN 978-94-010-4768-5 printed an acid-free paper AII Rights Reserved © 1993 Springer Science+Business Media Oordrecht Originally published by Kluwer Academic Publishers in 1993 Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover lst edition 1993 No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. -

Political Theory

Political Theory Themes for Comprehensive Examinations: 2020-21 The first theme, comprised of core works in the history of political thought, is required for all students being examined in the field of political theory. Students majoring in the field are responsible for four additional themes; students offering political theory as a minor field are responsible for two additional themes. N.B. : The theme bibliographies listed here are advisory only (except in the case of the “core” theme); they do not constitute necessary and sufficient lists of the works for which students will be held responsible. A written contract regarding the parameters and bibliography for each theme must be worked out by the student and relevant faculty. Examination format: Questions may integrate material from more than one theme prepared by the student, or may be specific to one theme. Students majoring in the field will answer three out of five questions, of which at least one question will involve material from the core theme. Students minoring in the field will answer two out of three questions. Theme 1: History of Political Thought (Required) For example: Socrates, “Apology” and “Crito” Plato, Republic Aristotle, Politics Augustine, City of God Aquinas, The Political Writings of St. Thomas Aquinas (Bigongiari, ed.) Machiavelli, Prince and Discourses Hobbes, Leviathan Locke, Second Treatise of Government Rousseau, Essay on the Origin of Inequality and Social Contract Marx, On the Jewish Question; Economic and Political Manuscripts of 1844; Communist Manifesto; -

Somaesthetics at the Limits Richard Shusterman

Somaesthetics at the Limits Richard Shusterman I Morten Kyndrup kindly invited me to open this conference by sketch- ing how the problematic question of limits has pervaded the contempor- ary field of aesthetics, and he suggested I do so by sketching how the issue of limits has shaped my own trajectory from analytic philosophy to pragmatism and continental theory and into the interdisciplinary field of somaesthetics.* Reviewing my almost thirty-year career in philosophical aesthetics, I realize that much of it has been a struggle with the limits that define this field, though I did not always see it in those terms. When I was still a student at Oxford specializing in analytic aesthetics, my first three publications were papers protesting the limits of prevail- ing monistic doctrines in that field: theories claiming that poetry (and by extension literature in general) is essentially an oral-based performative art without real visual import, and theories arguing that beneath the vary- ing interpretations and evaluations of works of art there was nonetheless one basic logic of interpretation and one basic logic of evaluation (though philosophers differed as to what that basic logic was and whether it was the same for both interpretation and evaluation). When I proposed con- trastingly pluralistic accounts of interpretive and evaluative logic, while suggesting that literature could be appreciated in terms of sight as well as sound, I was not consciously aiming at transgressing prevailing limits. I was more interested in being right than in