The Uranium Curse - the Northen Niger's Su Ering from Its Wealth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Insecurity Situations, the National Society (NS) Has Better Equipped Branches, Has Trained More Volunteers and More Technical Staff Are Recruited at Headquarters

DREF operation n° Niger: Food MDRNE005 GLIDE n° OT-2010000028- NER Insecurity 23 February, 2010 The International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of national societies to respond to disasters. CHF 229,046 (USD 212,828 or EUR 156,142) has been allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the Red Cross Society of Niger in delivering immediate assistance to some 300,000 beneficiaries. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. Summary: This DREF aims to mitigate the food shortage due to bad harvests last year affecting about half of the population (7.7 million) of Niger. The DREF is issued to respond to a request from the Red Cross Society of Niger (RCSN) to support sectors of food security and nutrition for about Red Cross supported Graham bank in Zinder. 300,000 people with various activities including cash for work, water harvesting and environmental protection actions, seeds and stock distribution, and support to nutrition centres. This operation is expected to be implemented over 2 months, and will therefore be completed by 23 April, 2010; a Final Report will be made available three months after the end of the operation (by July, 2010). An emergency appeal is in preparation to extend the activities until the harvest time in October or November, 2010. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

Proposed Proforma for Weekly Emrgency Situation

NIGER SITUATION REPORT Reporting period: 2-15 February 2007 Date of report: 16 February 2007 1) Significant events • The National Food Security Mechanism was soon have more than 70,000 mt of cereals in stock. • A mid-term evaluation of the PRRO is ongoing. • A nomadic rebel group attacked the town of Iferouane on 8 February killing three Nigerien soldiers. 2) Security Niger is under security phase 0, with the exception of Agadez and Diffa regions which are under phase 1. A nomadic rebel group attacked the remote north-eastern town of Iferouane (Agadez region) on 8 February, kidnapping two Nigerien soldiers and killing three more. Numerous nomadic groups in Niger's desert north staged an uprising in the 1990s and most groups accepted peace deals in 1995 but insecurity remains rife, with frequent acts of banditry, carjacking and kidnapping by former rebels. 3) Food security and nutritional situation Food prices are beginning to rise as household stocks decrease with the onset of the lean season. The Government’s market monitoring system (SIMA) reports that in January 2007, the prices of millet, sorghum and niébé (cow peas) all increased. Results of the Government/WFP/FAO joint household food security vulnerability assessment (November 2006) are finalized and are awaiting Government approval for circulation. At the National Food Mechanism CRC meeting of 6 February 2007, it was announced that, with food arrivals and confirmed contributions, the NFSM physical stocks will soon total over 70,000 mt- close to the 80,000 mt target level. Thanks to good donor support, this stock level will allow the mechanism an adequate response level. -

Overview of Key Livelihood Activities in Northern Niger

Research Paper November 2018 Overview of Key Livelihood Activities in Northern Niger Rida LYAMMOURI RP-18/08 1 2 Overview of Key Livelihood Activities in Northern Niger RIDA LYAMMOURI 3 About OCP Policy Center The OCP Policy Center is a Moroccan policy-oriented think tank based in Rabat, Morocco, striving to promote knowledge sharing and to contribute to an enriched reflection on key economic and international relations issues. By offering a southern perspective on major regional and global strategic challenges facing developing and emerging countries, the OCP Policy Center aims to provide a meaningful policy-making contribution through its four research programs: Agriculture, Environment and Food Security, Economic and Social Development, Commodity Economics and Finance, Geopolitics and International Relations. On this basis, we are actively engaged in public policy analysis and consultation while promoting international cooperation for the development of countries in the southern hemisphere. In this regard, the OCP Policy Center aims to be an incubator of ideas and a source of forward thinking for proposed actions on public policies within emerging economies, and more broadly for all stakeholders engaged in the national and regional growth and development process. For this purpose, the Think Tank relies on independent research and a solid network of internal and external leading research fellows. One of the objectives of the OCP Policy Center is to support and sustain the emergence of wider Atlantic Dialogues and cooperation on strategic regional and global issues. Aware that achieving these goals also require the development and improvement of Human capital, we are committed through our Policy School to effectively participate in strengthening national and continental capacities, and to enhance the understanding of topics from related research areas. -

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger Analysis Coordination March 2019 Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Acknowledgements This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Recommended Citation FEWS NET. 2019. Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger. Washington, DC: FEWS NET. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Ref Agadeza1.Pdf

REGION D'AGADEZ: Carte référentielle Légende L i b y e ± Chef lieu de région Chef lieu de département localité Route principale Route secondaire ou tertiaire Frontière internationale Frontière régionale Cours d'eau MADAMA Région d'Agadez A l g é r i e ☶ Population Djado DJABA DJADO CHIRFA KANARIA I-N-AZAOUA SARA BILMA DAOTIMMI I-N-TADERA ☶ 17 459 TOUARET SEGUEDINE IFEROUANE TAGHAJIT TAMJIT TAZOUROUTETASSOS INTIKIKITENE OURARENE AGALANGAÏ ☶ 32 864 DOUMBA EZAZAW FARAZAKAT ANEY ASSAMAKKA ABARGOT TEZIRZEK LOTEY TCHOUGOY TIRAOUENE TAKARATEMAMANAT ZOURIKA EMI TCHOUMA AZATRAYA AGREROUM ET TCHWOUN ARLIT Gougaram ACHENOUMA IFEROUANE ISSAWANE ARRIGUI Dirkou ACHEGOUR TEMET DIRKOU ☶ 103 369 INIGNAOUEI TILALENE ARAKAW MAGHET TAKRIZA TARHMERT ARLIT AGAMGAM BILMA ANOU OUACHCHERENE TCHIGAYEN TAZOURAT TAGGAFADI Dannet GOUGARAM SIDAOUET ZOMO ASSODE IBOUL TCHILHOURENE ERISMALAN TIESTANE Bilma MAZALALE AJIWA INNALARENE TAZEWET AGHAROUS ESSELEL ZOBABA ANOUZAGHARAN DANNET FAYAYE Timia FACHI TIGUIR AJIR IMOURAREN TIMIA FACHI MARI Fachi TAKARACHE ZIKAT OFENE MALLETAS AKEREBREB ABELAJOUAD TCHINOUGOUWENEARITAOUA IN-ABANGHARIT TAMATEDERITTASSEDET ASSAK HARAU INTAMADE T c h a d EGHARGHAR TILIA OOUOUARI Dabaga ELMEKI BOURNI TIDEKAL SEKIRET ASSESA MERIG AKARI TELOUES EGANDAWEL AOUDERAS EOULEM SOGHO TAGAZA ATKAKI TCHIROZERINE TABELOT EGHOUAK M a l i AZELIK DABLA ABARDOKH TALAT INGAL IMMASSATANE AMAN NTEDENT ELDJIMMA ☶ 241 007 GUERAGUERA TEGUIDDA IN TESSOUM ABAZAGOR Tabelot FAGOSCHIA DABAGA TEGUIDDA IN TAGAIT I-N-OUTESSANE ☶ EKIZENGUI AGALGOU 51 818 TCHIROZERINE INGOUCHIL -

F:\Niger En Chiffres 2014 Draft

Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 1 Novembre 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Direction Générale de l’Institut National de la Statistique 182, Rue de la Sirba, BP 13416, Niamey – Niger, Tél. : +227 20 72 35 60 Fax : +227 20 72 21 74, NIF : 9617/R, http://www.ins.ne, e-mail : [email protected] 2 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Pays : Niger Capitale : Niamey Date de proclamation - de la République 18 décembre 1958 - de l’Indépendance 3 août 1960 Population* (en 2013) : 17.807.117 d’habitants Superficie : 1 267 000 km² Monnaie : Francs CFA (1 euro = 655,957 FCFA) Religion : 99% Musulmans, 1% Autres * Estimations à partir des données définitives du RGP/H 2012 3 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 4 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Ce document est l’une des publications annuelles de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Il a été préparé par : - Sani ALI, Chef de Service de la Coordination Statistique. Ont également participé à l’élaboration de cette publication, les structures et personnes suivantes de l’INS : les structures : - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Economiques (DSEE) ; - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Démographiques et Sociales (DSEDS). les personnes : - Idrissa ALICHINA KOURGUENI, Directeur Général de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Ibrahim SOUMAILA, Secrétaire Général P.I de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Ce document a été examiné et validé par les membres du Comité de Lecture de l’INS. Il s’agit de : - Adamou BOUZOU, Président du comité de lecture de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Djibo SAIDOU, membre du comité - Mahamadou CHEKARAOU, membre du comité - Tassiou ALMADJIR, membre du comité - Halissa HASSAN DAN AZOUMI, membre du comité - Issiak Balarabé MAHAMAN, membre du comité - Ibrahim ISSOUFOU ALI KIAFFI, membre du comité - Abdou MAINA, membre du comité. -

Type of the Paper (Article

Supplementary material Supplementary Table 1. Departmental flood statistics (SA = settlements affected; PA = people affected; HD = houses destroyed; CL = crop losses (ha); LL = livestock losses Y = number of years with almost a flood). CL LL DEPARTMENT REGION SA PA HD YEARS (ha) (TLU) 2007; 2009; 2012; 2013; ABALA TILLABERI 54 22263 1140 151 1646 2015 ABALAK TAHOUA 1 4437 570 52 6 2011 ADERBISSINAT AGADEZ 8 15931 223 1 2382 2010; 2013 2001; 2010; 2013; 2014; AGUIE MARADI 36 14420 1384 158 3 2015 2005; 2007; 2009; 2010; ARLIT AGADEZ 34 9085 166 19 556 2011; 2013; 2015 AYEROU TILLABERI 8 3430 25 197 2480 2008; 2010; 2012 BAGAROUA TAHOUA 25 9780 251 0 28 2014; 2015 2006; 2010; 2011; 2012; BALLEYARA TILLABERI 41 14446 13 2697 2 2014 BANIBANGOU TILLABERI 7 1400 154 204 3574 2006; 2010; 2012 BANKILARE TILLABERI 0 0 0 0 0 BELBEDJI ZINDER 1 553 5 0 0 2010 BERMO MARADI 10 12281 73 0 933 2010; 2014; 2015 BILMA AGADEZ 0 0 0 0 0 1999; 2006; 2008; 2014; BIRNI NKONNI TAHOUA 27 28842 343 274 1 2015 1999; 2000; 2003; 2006; 2008; 2009; 2010; 2011; BOBOYE DOSSO 159 30208 3412 2685 1 2012; 2013; 2014; 2015; 2016 BOSSO DIFFA 13 2448 414 24 0 2007; 2012 BOUZA TAHOUA 9 2070 303 28 0 2007; 2015 2001; 2010; 2012; 2013; DAKORO MARADI 20 15779 728 59 2 2014; 2015 DAMAGARAM 2002; 2009; 2010; 2013; ZINDER 13 10478 876 777 596 TAKAYA 2014 DIFFA DIFFA 23 2856 271 0 0 1999; 2010; 2012; 2013 DIOUNDIOU DOSSO 55 14621 1577 1660 0 2009; 2010; 2012; 2013 1999; 2002; 2003; 2005; 2006; 2008; 2009; 2010; DOGONDOUTCHI DOSSO 128 52774 3245 577 23 2012; 2013; 2014; 2015; 2016 -

Arrêt N° 012/11/CCT/ME Du 1Er Avril 2011 LE CONSEIL

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 012/11/CCT/ME du 1er Avril 2011 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du premier avril deux mil onze tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la Constitution ; Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-096 du 28 décembre 2010 portant code électoral ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2011-121/PCSRD/MISD/AR du 23 février 2011 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le deuxième tour de l’élection présidentielle ; Vu l’arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 portant validation des candidatures aux élections présidentielles de 2011 ; Vu l’arrêt n° 006/11/CCT/ME du 22 février 2011 portant validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour du 31 janvier 2011 ; Vu la lettre n° 557/P/CENI du 17 mars 2011 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante transmettant les résultats globaux provisoires du scrutin présidentiel 2ème tour, aux fins de validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 028/PCCT du 17 mars 2011 de Madame le Président du Conseil constitutionnel portant -

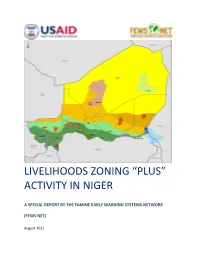

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

STUDY REPORT on COMMUNITY INTEGRATION and PERCEPTIONS of BORDER SECURITY in the AGADEZ REGION Acknowledgements

STUDY REPORT ON COMMUNITY INTEGRATION AND PERCEPTIONS OF BORDER SECURITY IN THE AGADEZ REGION Acknowledgements Our thanks go first to Mr Daouda Alghabid, Security Advisor to the Prime Minister, Head of Government of the Niger, as well as to the Ministry of the Interior, Public Security, Decentralization and Customary and Religious Affairs. Their active support for the project “Engaging Communities in Border Management in Niger”, of which this study is an essential element, enables the International Organization for Migration (IOM) to work under the best possible conditions. More specifically, IOM wishes to thank the Governor of the Agadez region, the President of the Regional Council and the Prefects and Mayors of the departments and municipalities involved for their invaluable assistance in both preparing and conducting the survey. IOM Niger also thanks the Sultan of Aïr, the canton and group chiefs, as well as the village chiefs of the Agadez region for mobilizing the communities covered by the survey. The departmental and municipal youth councils also contributed to the smooth running of the field investigators’ mission. We thank them for that. Finally, our thanks go naturally to the donor who made this study possible, the United States Department of State. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. -

Eperonner Le Monde. Nomadisme, Cosmos Et Politique Chez Les Touaregs Hélène Claudot-Hawad

Eperonner le monde. Nomadisme, cosmos et politique chez les Touaregs Hélène Claudot-Hawad To cite this version: Hélène Claudot-Hawad. Eperonner le monde. Nomadisme, cosmos et politique chez les Touaregs. Edisud, 199 p., 2001. halshs-00474014 HAL Id: halshs-00474014 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00474014 Submitted on 18 Apr 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Couv Eperonn2 4/07/07 14:29 Page 1 ÉSORDRE NOMADE ou ordre différent ? Les idées, les valeurs, les Ddécisions et les actions qui ont façonné l’histoire touarègue ont souvent été décryptées par les regards extérieurs comme les débordements chaotiques d’un monde sans foi ni loi. Croisant les sources externes et internes, ces textes explorent au contraire la question désertée et cependant centrale du “politique” dans cette société nomade. Ils s’attachent à dégager les modèles originaux mis en œuvre et les principes structurants de l’ordre social, qui font écho à la vision touarègue de l’ordre cosmique. Ils analysent leurs interactions, leurs transformations et leurs recompositions en cette période troublée qui s’étend de la fin du XIXe siècle jusqu’à l’orée du XXIe siècle.