Delaware Anti-Bullying Laws 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charter School Pcard and Personal Reimbursement Expenditures Inspection

State of Delaware Office of Auditor of Accounts Charter School1 PCard and Personal Reimbursement Expenditures Inspection Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2014 Inspection Issuance Date: September 30, 2015 R. Thomas Wagner, Jr., CFE, CGFM, CICA Auditor of Accounts 1 MOT Charter School, Thomas A. Edison Charter School, Delaware College Preparatory Academy, and Kuumba Academy Charter School State of Delaware Office of Auditor of Accounts R. Thomas Wagner, Jr., CFE, CGFM, CICA At a Glance Working Hard to Protect YOUR Tax Dollars Why We Did This What We Found Inspection The Office of Auditor of Accounts (AOA) is pleased to report that MOT This engagement was Charter School and Thomas A. Edison Charter School consistently got it performed as a result of right by establishing and following internal controls, which helped ongoing data analysis and ensure compliance with rules and regulations. The same cannot be said for Delaware College Preparatory Academy (DCPA) and Kuumba monitoring performed by Academy Charter School (KACS.) staff at the Office of Auditor of Accounts. The DCPA Board President claimed she made an unrecorded related party loan to the school. As part of her response to the otherwise We are very pleased with the untraceable arrangement, she provided a letter dated in August 2011 in results of our procedures at which she approves her loan to the school. The lack of appropriate MOT Charter School and accounting and related party disclosure aside, she stated she was not Thomas A. Edison Charter aware of the “why and how’s of the [$11,252.87 in] transactions” for School and appreciate their which she was reimbursed. -

MOT Charter School

EMPLOYEE HANDBOOK Table of Contents Welcome to MOT Charter School ............................................................................................. 1 How You Were Selected ........................................................................................................................... 1 Introductory Period .................................................................................................................................... 1 About MOT Charter School ...................................................................................................... 3 Organizational Chart ................................................................................................................. 5 General Employment Policies ................................................................................................... 7 At-Will Employment .................................................................................................................................... 7 Attendance .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Alcohol, Drugs, and Controlled Substances ....................................................................................... 8 Confidentiality ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Customer Relations ................................................................................................................................... -

Chapter List

Delaware TSA Chapters 2018 Appoquinimink School District First State Military Academy AG Water Middle School First State Military Academy (High School) Appoquinimink High School Meredith Middle School Indian River School District Middletown High School Indian River High School Redding Middle School Selbyville Middle School Sussex Central High School Brandywine School District Brandywine High School Lake Forest School District Concord High School Lake Forest High School Mt. Pleasant High School W. T. Chipman Middle School P. S. duPont Middle School Springer Middle School Milford School District Talley Middle School Milford Senior High School Caesar Rodney School District M.O.T. Charter Caesar Rodney High School MOT Charter School (High School) Dover Air Base Middle School MOT Charter School (Middle School) Fifer Middle School Postlethwait Middle School Newark Charter School Newark Charter School (High School) Cape Henlopen School District Beacon Middle School Odyssey Charter Cape Henlopen High School Odyssey Charter (High School) Mariner Middle School Prestige Academy Capital School District Dover High School Prestige Academy (Middle School) Christina School District Red Clay School District Bayard Intermediate A.I. duPont High School Christiana High School Cab Calloway School of the Arts (High School) Gauger-Cobbs Middle School Cab Calloway School of the Arts (Middle School) Glasgow High School Conrad Schools of Science (High School) Kirk Middle School Conrad Schools of Science (Middle School) Newark High School Dickinson High School -

Delaware Technology Student Association (DETSA) 2019 State

Delaware Technology Student Association (DETSA) 2019 State Conference Results Updated 4.8.19 April 3, 2019 Place Level Title School & Participant Name Dr. John John Dickinson High School - Kathryn Sheehy Dr. John Brown Award Brown Special Awards Advisor of the Year Award P. S. duPont Middle School – Stephen Lee Highest Test Score - Middle Middle School P. S. duPont Middle School - Sahil Langot School Tech Bowl Highest Highest Test Score - High Test High School Brandywine High School – Jackson Bliey School Technology Bowl Score Highest Test Score - Middle Middle School H.B. duPont Middle School - Crystal Lu School Electrical Applications 3 Newark Charter High School - Matthew Abraham Sussex Academy - Mary Garcia-Barrios; Prabh Kaur; Brandon 2 Maccubbin; Jezzelle Repalbor; Kale Showers; Margaret Vazquez High School Architectural Design Caesar Rodney High School - Graham Cooper; Adam Hanna; 1 Silvana Nasim; Sophia Weldin; Meghana Yarlagadda 3 Concord High School - Christy Chacko; Peyton Jenkins 2 Sussex Central High School - Colby Fox; Jack Gartman High School Board Game Design Newark Charter High School - Andrew Blackburn; Daniel Davis; 1 Adam Dickert; Shaun Huebner; James Stokes 2 John Dickinson High School - Brianna Rivera High School CAD Architecture 1 John Dickinson High School - Robert Mossinger 3 Newark Charter High School - Gina New 2 High School CAD Engineering Caesar Rodney High School - Nathaniel Prystash 1 Caesar Rodney High School - Nate Allen 3 Gauger-Cobbs Middle School - Alexis Biah 2 Middle School Career Prep P. S. duPont -

New Castle County Expo 2014 PARTICIPANTS

New Castle County Expo 2014 PARTICIPANTS Schools Elementary: K-5 Delaware College Preparatory Academy identifies core Delaware College Preparatory Academy academic expectations to instill within students a set of Wilmington, DE values and habits to benefit them throughout their lives. www.DCPAcademy.org Students learn with a focus on college readiness. [email protected] (302) 762-7424 Elementary: K-1 (2015: K-2) La Academia offers a Spanish-immersion model, coupled La Academia Antonia Alonso with a project-based curriculum (Expeditionary Learning). Wilmington, DE The school is housed within the Community Education AcademiaCharter.com Building. (302) 660-3746 Elementary/Middle School, K-6 First State Montessori Academy provides parents and students with an authentic, time-tested, Montessori education in a public school. Core components include First State Montessori Academy personalized instruction, multi-age classrooms, uninterrupted blocks of learning time, and instruction Wilmington, DE from two teachers in each classroom. www.FirstStateMontessori.org [email protected] Elementary/Middle School, K-8 ASPIRA is a Spanish/English dual-language charter school. Within the 7-year program students will become bilingual, Las Americas ASPIRA Academy bi-literate and bi-cultural, while gaining the academic skills Newark, DE to succeed in school and life. www.AspiraAcademy.org (302) 292-1463 Elementary/Middle School, K-6 (2014: K-7) Kuumba Academy incorporates the arts into education. Kuumba’s curriculum focuses on developing the “whole Kuumba Academy Charter School child”. Kuumba Academy is housed in the Community Wilmington, DE Education Building in Wilmington. www.KuumbaAcademy.org (302) 472-6450 Elementary/Middle School, PK-8 EastSide offers a strong educational program for EastSide Charter School elementary and middle school students in New Castle County. -

Smarter Charter-Schools

Delaware Department of Education 2015-16 STATE CHARTER REPORT 1 Table of Contents _Toc473616053 Report Overview ....................................................................................................................................3 General Charter School Information ......................................................................................................4 Charter School Enrollment ....................................................................................................................5 Revenue and Expenditure Comparison ..................................................................................................7 Charter School Performance Framework.............................................................................................12 Academic Performance Data ...............................................................................................................12 Organizational Performance Framework .............................................................................................17 2015-2016 Overall Organizational Performance Ratings ....................................................................18 2015-2016 Education Program Indicator Rating ............................................................................. 18 2015-2016 Financial Management and Oversight Indicator Rating ............................................... 19 2015-2016 Governance and Reporting Indicator Rating ................................................................. 19 2015-2016 -

How Intra-District School Choice and Competition Among Schools Impacts School Leadership

HOW INTRA-DISTRICT SCHOOL CHOICE AND COMPETITION AMONG SCHOOLS IMPACTS SCHOOL LEADERSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF SECONDARY SCHOOL PRINCIPALS by Christopher M. Kohan Liberty University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University 2018 2 HOW INTRA-DISTRICT SCHOOL CHOICE AND COMPETITION AMONG SCHOOLS IMPACTS SCHOOL LEADERSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF SECONDARY SCHOOL PRINCIPALS by Christopher M. Kohan A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA 2018 APPROVED BY: Ralph Marino, Jr., Ed.D., Committee Chair Jared Bigham, Ed.D., Committee Member Lisa Ueltzhoffer, Ed.D., Committee Member 3 ABSTRACT The purpose of this qualitative, explanatory case study was to describe how traditional, magnet, and charter school principals in one Delaware school district responded to an environment of total school choice and how they made sense of their roles as a principal in the era of school choice. Hess’s (2010) organizational theory was the theoretical foundation for this study as selective enrollment schools, such as magnet and charter schools, would have direct and indirect effects on traditional schools The research questions for this study were: (a) How do traditional, magnet, and charter school principals make sense of the competition generated by school choice options; (b) how do traditional, magnet, and charter school principals perceive the competition of how school choice impacts their responsibilities as school leaders; and (c) how do traditional, magnet, and charter school principals perceive the competition of how school choice impacts the long-term operations of the school? The results were from 11 individual principal semi- structured interviews, 11 administrative questionnaires, 11 school choice event observations, and artifact analysis were used as gathered data and were analyzed through hand coding and recoding. -

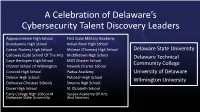

Cyber Recognition

A Celebration of Delaware’s Cybersecurity Talent Discovery Leaders Appoquinimink High School First State Military Academy Brandywine High School Indian River High School Caesar Rodney High School Mckean (Thomas) High School Delaware State University Calloway (Cab) School Of The Arts Middletown High School Delaware Technical Cape Henlopen High School MOT Charter School Community College Charter School Of Wilmington Newark Charter School Concord High School Padua Academy University of Delaware Delmar High School Polytech High School Wilmington University Delmarva Christian Schools Smyrna High School Dover High School St. Elizabeth School Early College High School At Sussex Academy Of Arts Delaware State University And Sciences The challenge they are helping to solve • Online technologies and cyber criminal techniques are becoming more sophisticated. Cyber risk is now a greater concern for CEOs than recession (Fortune Magazine). • There is a significant global shortage of skilled, trained cyber security professionals. Many talented young people have no idea this is an area where they could excel or how much fun it can be. • To fill this critical manpower gap, many more young people need to be offered the opportunity to discover whether they like the challenges and whether they have the aptitude to excel. The UK’s discovery: CyberStart A suite of challenges and games that: • Introduce young people to the field of cyber security • Develop and nurture their interest in the subject • Inspire them to pursue careers within the sector Part 1. Delaware’s High School Leaders (Girls participating) MOT Charter School 28 Delaware high school teachers Padua Academy 28 encouraged 143 girls to try Charter School Of Wilmington 18 CyberStart – ranking the state 8th out of 27 states in participants per Newark Charter School 12 million. -

Copy of Fall 2019 Data Pages 4 to End Incomplete SS.Xlsx

Enrollment Report Fall 2019 Office of Institutional Research Fall 2019 Enrollment Report Table of Contents Key Findings 3 Fall 2019 College Enrollment Summary 4 Graduate Student Profile 5 Fall 2019 Graduate Student Enrollment Summary 6 Applied, Accepted & Enrolled for Fall 2019, First‐Time Graduate Students 7 Graduate Applicants and Enrolled Student’s Most Recent Prior College 8 Graduate Enrollment at SUNY Campuses 9 Undergraduate Student Profile 10 Fall 2019 Undergraduate Enrollment Summary 11 Undergraduate Student Body by Gender, Permanent Residence and Age 2010‐2019 12 County of Permanent Residence, Fall 2019 Undergraduate Students 13 Distribution of Undergraduate Student Enrollment by Ethnicity Fall 2015‐2019 14 Applied, Accepted & Enrolled for Fall 2017 to Fall 2019, First‐Time Students 15 Applied, Accepted & Enrolled for Fall 2017 to Fall 2019, Transfer Students 16 Applied, Accepted & Enrolled for Fall 2017 to Fall 2019, Transfer & First‐Time Combined 17 Undergraduate Enrollment at SUNY Campuses 18 Undergraduate Enrollment by Student Type and Primary Major 19 Undergraduate Enrollment by Curriculum 2010 to 2019 20 New Transfer Students by Curriculum Fall 2015 to Fall 2019 21 New Freshmen Selectivity 22 Top 50 Feeder High Schools by Number of Students Registered 23 Top 50 Feeder High Schools by Number of Students Accepted 24 Alphabetical Listing of Feeder High Schools 25 Most Recent Prior Colleges of Transfer Applicants Sorted by Number Registered 49 New Transfer Students Most Recent Prior College 57 Fall 2019 Enrollment Report Key Findings Graduate Students Enrollment in the Master of Science in Technology Management program remained steady at 57 students in Fall 2019 compared to 54 in Fall 2018. -

Fiscal Year 2021 Preliminary Budget August 2020

Fiscal Year 2021 Preliminary Budget August 2020 Table of Contents I. Introduction A. Beliefs of the Board B. Budget Process C. Influencing Factors II. Local Revenue A. Tax Warrant B. Charter/Choice C. State Funding – Student Enrollment D. Federal Funding III. Operating Budget – Agency 953300 – Regular Schools (plus 955900 ILC) A. Revenue B. Expense C. School Discretionary Budget D. Federal Consolidated Grant IV. Tuition Based Agencies A. Delaware School for the Deaf (Agency 955100) B. REACH (Agency 955600) C. Delaware Autism Program (Agency 956000) V. Glossary of Terms - 2 - August 2020 I. Introduction The preparation of the preliminary District budget begins in January, after the release of the Governor’s proposed State operating budget. Over the winter and spring, the General Assembly’s Joint Finance Committee and Joint Capital Improvement Committees hold hearings and modify the Governor’s recommended operating and capital budgets. The budgets are approved by the General Assembly prior to the governor’s approval. The state budget has a significant direct impact on school funding. This year, the state provided ongoing support for recently created programs designed to provide additional support for schools with high concentrations of poverty and or English language learners. In addition, the state also is providing support for basic special education students in grades kindergarten through 3rd grade. These programs, in some circumstances provide the opportunity for School Boards to provide supplemental funding through a match tax. The District and the State are also working on a Wilmington Schools Initiative that is providing supplemental operating and capital funds. This opportunity, as well as the proposed budget, aligns with the beliefs of the Christina School District Board of Education. -

School Districts – Kindergarten/Enrollment Information

School Districts – Kindergarten/Enrollment Information Appoquinimink School District • 302-376-4128 118 South Street, Odessa, DE 19730 http://www.apposchooldistrict.com/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=184804&type=d Brandywine School District • 302-793-5000 1311 Brandywine Boulevard, Wilmington, DE 19809 https://www.brandywineschools.org/Domain/95 Caesar Rodney School District • 302-698-4800 7 Front Street, Wyoming, DE 19934 https://www.crk12.org/domain/630 Cape Henlopen School District • 302-645-6686 1270 Kings Highway, Lewes, DE 19958 https://www.capehenlopenschools.com/domain/145 Capital School District • 302-672-1500 198 Commerce Way, Dover, DE 19904 http://www.capital.k12.de.us/page/3274 Christina School District • 302-552-2600 600 North Lombard Street, Wilmington, DE 19801 https://www.christinak12.org/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=335799&type=d Colonial School District • 302-323-2700 318 East Basin Road, New Castle, DE 19720 http://www.colonialschooldistrict.org/registration/kindergarten/ Indian River School District • 302-436-1000 31 Hosier Street, Selbyville, DE 19975 http://www.irsd.net/parents___students/registration Lake Forest School District • 302-284-3020 5423 Killens Pond Road, Felton, DE 19943 http://www.lf.k12.de.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/2017-Kindergarten-FLYER.pdf Laurel School District • 302-875-6100 1160 South Central Avenue, Laurel, DE 19956 http://www.laurel.k12.de.us/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=191771&type=d Milford School District • 302-422-1600 906 Lakeview Avenue, Milford, DE 19963 http://milfordschooldistrict.org/ourpages/auto/2010/11/4/51344307/Milford%20School%20District -

Status of Public Education for City of Wilmington Students 2016–17 School Year Data Report

Wilmington Education Improvement Commission Status of Public Education for City of Wilmington Students 2016–17 School Year Data Report April 2018 Prepared by the Institute for Public Administration School of Public Policy & Administration College of Arts & Sciences University of Delaware This page is left intentionally blank. i Introduction Prepared by the University of Delaware’s Institute for Public Administration for the Wilmington Education Improvement Commission, this report provides an updated analysis of enrollment, student proficiency, graduation rates, and dropout rates for P–12 students residing within the limits of the City of Wilmington. This includes students attending traditional, vocational-technical (vo-tech), and charter schools across the state during the 2016–17 school year. The report provides a snapshot of public education for students living in the City of Wilmington. The Wilmington Education Improvement Commission (the Commission) was created through legislation to advise the Governor and General Assembly on how to improve the quality and availability of education for children P–12 within the City of Wilmington; recommend actions to address the needs of all schools statewide that have high concentrations of students in poverty; English language learners (ELLs), and other students at risk; and carry out the action agenda developed by the Wilmington Education Advisory Committee as described in Strengthening Wilmington Education: An Action Agenda. Building on the Wilmington Education Advisory Committee’s recommendations, the Commission adopted a framework for change that streamlines three areas of critical importance for improving the education system and student outcomes: creating more responsive governance, funding student success, and meeting student needs. The agenda’s recommendations focused on City of Wilmington students but also addressed needs of the statewide education system.