Early Town Planning System of Small Towns in Perak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Heavy Metals in Lakes of Former Tin Mining Sites in the City of Ipoh, Perak, Malaysia

An Analysis of Heavy Metals in Lakes of Former Tin Mining Sites in the City of Ipoh, Perak, Malaysia Mohmadisa Hashim, Wee Fhei Shiang, Zahid Mat Said, Nasir Nayan, Hanifah Mahat & Yazid Saleh To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i2/3977 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i2/3977 Received: 29 Dec 2017, Revised: 03 Feb 2018, Accepted: 10 Feb 2018 Published Online: 13 Feb 2018 In-Text Citation: (Hashim et al., 2018) To Cite this Article: Hashim, M., Shiang, W. F., Said, Z. M., Nayan, N., Mahat, H., & Saleh, Y. (2018). An Analysis of Heavy Metals in Lakes of Former Tin Mining Sites in the City of Ipoh, Perak, Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(2), 673–683. Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 8, No.2, February 2018, Pg. 673 – 683 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 8 , No.2, February 2018, -

Guideline for Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of MSW Landfill Sites

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY MINISTRY OF HOUSING AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT, MALAYSIA THE STUDY ON THE SAFE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF LANDFILL SITES IN MALAYSIA FINAL REPORT Volume 3 Guideline for Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of MSW Landfill Sites NOVEMBER 2004 YACHIYO ENGINEERING CO., LTD. EX CORPORATION The Final Report of “The Study on The Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of Landfill Sites in Malaysia” is composed of seven Volumes as shown below: Volume 1 Summary Volume 2 Main Report Volume 3 Guideline for Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of MSW Landfill Sites Volume 4 Pilot Projects on Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of Landfill Sites Volume 5 Technical Guideline for Sanitary Landfill, Design and Operation (Revised Draft, 2004) Volume 6 User Manual of LACMIS (Landfill Closure Management Information System) Volume 7 Data Book This Report is “Volume 3 Guideline for Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of MSW Landfill Sites”. Guideline for Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of MSW Landfill Sites (Draft) Part I : General Part II : Technical Requirements Appendices Ministry of Housing and Local Government MALAYSIA GUIDELINE FOR SAFE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF MSW LANDFILL SITES CONTENTS Contents Abbreviations Part I General..................................................................................................................I-1 I-1 Purpose of the Guideline·····························································································I-1 I-2 Scope of the Guideline································································································I-2 -

Remembering the Dearly Departed

www.ipohecho.com.my IPOH echoechoYour Community Newspaper FREE for collection from our office and selected outlets, on 1st & 16th of the month. 30 sen for delivery to your ISSUE JULY 1 - 16, 2009 PP 14252/10/2009(022651) house by news vendors within Perak. RM 1 prepaid postage for mailing within Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei. 77 NEWS NEW! Meander With Mindy and discover what’s new in different sections of Ipoh A SOCIETY IS IPOH READY FOR HIDDEN GEMS TO EMPOWER THE INTERNATIONAL OF IPOH MALAYS TOURIST? 3 GARDEN SOUTH 11 12 REMEMBERING THE DEARLY DEPARTED by FATHOL ZAMAN BUKHARI The Kamunting Christian Cemetery holds a record of sorts. It has the largest number of Australian servicemen and family members buried in Malaysia. All in all 65 members of the Australian Defence Forces were buried in graves all over the country. Out of this, 40 were interred at the Kamunting burial site, which is located next to the Taiping Tesco Hypermarket. They were casualties of the Malayan Emergency (1948 to 1960) and Con- frontation with Indonesia (1963 to 1966). continued on page 2 2 IPOH ECHO JULY 1 - 16, 2009 Your Community Newspaper A fitting service for the Aussie soldiers who gave their lives for our country or over two decades headstones. Members, Ffamilies and friends their families and guests of the fallen heroes have then adjourned to the been coming regularly Taiping New Club for to Ipoh and Taiping to refreshments. honour their loved ones. Some come on their own Busy Week for Veterans while others make their The veterans made journey in June to coincide full use of their one-week with the annual memorial stay in Ipoh by attending service at the God’s Little other memorial services Acre in Batu Gajah. -

Routes Transportation Problem for Waste Collection System at Sitiawan, Perak, Malaysia

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-9 Issue-2, December 2019 Routes Transportation Problem for Waste Collection System at Sitiawan, Perak, Malaysia Shaiful Bakri Ismail, Dayangku Farahwaheda Awang Mohammed daily work routine depended on what types of business is it. Abstract: Green logistic concept has emerged and inherently One of the examples is waste collection system in logistic driven by the environmental sustainability challenges. The sectors. The developing countries such as Malaysia cannot implementation of Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP) in real world escape from environmental problems such as pollution due to relates with Green Vehicle Routing Problem (GVRP). The recent urbanization and increased in population. So, the needs research is discussing about solving GVRP for waste collection system in Sitiawan, Perak. The purpose of this research is to to maintain and optimize in transportation sector in terms of design a vehicle routes selection for waste collection system using Green Vehicle Routing Problem (GVRP) will help in general optimization method and to examine the result associates minimizing the impact of environmental problems. Therefore, with GVRP. Travelling Salesman Problem (TSP) is used as main in this paper, waste collection system at Sitiawan, Perak, optimization method and simulated using MATLAB Malaysia is selected to solve GVRP using Travelling Programming. The expected outcome shown in this paper would Salesman Problem (TSP) method that able in achieving the be statistical analysis between actual routes and suggested routes research objectives. The objectives of GVRP include to find the best routes. Result shows that routes suggested by TSP had better efficiency about 0.32% which had less distance and 7% minimizing the time travelled, reducing fuel consumption, (392 minutes) less time than actual routes. -

A Taxonomic Revision of Araceae Tribe Potheae (Pothos, Pothoidium and Pedicellarum) for Malesia, Australia and the Tropical Western Pacific

449 A taxonomic revision of Araceae tribe Potheae (Pothos, Pothoidium and Pedicellarum) for Malesia, Australia and the tropical Western Pacific P.C. Boyce and A. Hay Abstract Boyce, P.C. 1 and Hay, A. 2 (1Herbarium, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AE, U.K. and Department of Agricultural Botany, School of Plant Sciences, The University of Reading, Whiteknights, P.O. Box 221, Reading, RS6 6AS, U.K.; 2Royal Botanic Gardens, Mrs Macquarie’s Road, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia) 2001. A taxonomic revision of Araceae tribe Potheae (Pothos, Pothoidium and Pedicellarum) for Malesia, Australia and the tropical Western Pacific. Telopea 9(3): 449–571. A regional revision of the three genera comprising tribe Potheae (Araceae: Pothoideae) is presented, largely as a precursor to the account for Flora Malesiana; 46 species are recognized (Pothos 44, Pothoidium 1, Pedicellarum 1) of which three Pothos (P. laurifolius, P. oliganthus and P. volans) are newly described, one (P. longus) is treated as insufficiently known and two (P. sanderianus, P. nitens) are treated as doubtful. Pothos latifolius L. is excluded from Araceae [= Piper sp.]. The following new synonymies are proposed: Pothos longipedunculatus Ridl. non Engl. = P. brevivaginatus; P. acuminatissimus = P. dolichophyllus; P. borneensis = P. insignis; P. scandens var. javanicus, P. macrophyllus and P. vrieseanus = P. junghuhnii; P. rumphii = P. tener; P. lorispathus = P. leptostachyus; P. kinabaluensis = P. longivaginatus; P. merrillii and P. ovatifolius var. simalurensis = P. ovatifolius; P. sumatranus, P. korthalsianus, P. inaequalis and P. jacobsonii = P. oxyphyllus. Relationships within Pothos and the taxonomic robustness of the satellite genera are discussed. Keys to the genera and species of Potheae and the subgenera and supergroups of Pothos for the region are provided. -

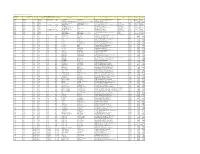

Inventory Stations in Perak 40 Jps 210 False 20 Jps 41.4 False 00 00 Jps 339 False 45 Jps 1390 False

INVENTORY STATIONS IN PERAK PROJECT STESEN STATION NO STATION NAME FUNCTION STATE DISTRICT RIVER RIVER BASIN YEAR OPEN YEAR CLOSE ISO ACTIVE MANUAL TELEMETRY LOGGER LATITUDE LONGITUDE OWNER ELEV CATCH AREA STN PEDALAMAN 3813414 Sg. Trolak di Trolak WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Trolak Sg. Bernam 1946 TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 03 53 30 101 22 45 JPS 65.8 FALSE 3814413 Sg. Slim At Kg. Slim WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Slim Sg. Bernam 1930 07/72 FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE 03 51 00 101 28 45 JPS 314 FALSE 3814415 Sg. Bil At Jln. Tg. Malim-Slim WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Bil Sg. Bernam 1946 07/83 FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 03 49 30 101 29 20 JPS 41.4 FALSE 3814416 Sg. Slim At Slim River WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Slim Sg. Bernam 11/66 TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE 03 49 35 101 24 40 JPS 455 FALSE 3901401 Sungai Bidor di Changkat Jong WL Perak Hilir Perak FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE 3.99 101.1 FALSE 3907403 Sg.Perak di Kg.Pasang Api, Bagan Datok WL Perak Hilir Perak Muara Sg. Perak FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE 3 59 17.37 100 45 55.69 FALSE 3911457 Sg. Sungkai At Jln. Anson-Kampar WL Perak Hilir Perak Sg. Sungkai Sg. Perak 1950 07/83 FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 03 59 20 101 07 30 JPS 479 FALSE 3913458 Sg. Sungkai di Sungkai WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Sungkai Sg. Perak 1930 TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE 03 59 15 101 18 50 JPS 289 FALSE 4011451 Sg. -

MISC. HERITAGE NEWS –March to July 2017

MISC. HERITAGE NEWS –March to July 2017 What did we spot on the Sarawak and regional heritage scene in the last five months? SARAWAK Land clearing observed early March just uphill from the Bongkissam archaeological site, Santubong, raised alarm in the heritage-sensitive community because of the known archaeological potential of the area (for example, uphill from the shrine, partial excavations undertaken in the 1950s-60s at Bukit Maras revealed items related to the Indian Gupta tradition, tentatively dated 6 to 9th century). The land in question is earmarked for an extension of Santubong village. The bulldozing was later halted for a few days for Sarawak Museum archaeologists to undertake a rapid surface assessment, conclusion of which was that “there was no (…) artefact or any archaeological remains found on the SPK site” (Borneo Post). Greenlight was subsequently given by the Sarawak authorities to get on with the works. There were talks of relocating the shrine and, in the process, it appeared that the Bongkissam site had actually never been gazetted as a heritage site. In an e-statement, the Sarawak Heritage Society mentioned that it remained interrogative and called for due diligences rules in preventive archaeology on development sites for which there are presumptions of historical remains. Dr Charles Leh, Deputy Director of the Sarawak Museum Department mentioned an objective to make the Santubong Archaeological Park a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2020. (our Nov.2016-Feb.2017 Newsletter reported on this latter project “Extension project near Santubong shrine raises concerns” – Borneo Post, 22 March 2017 “Bongkissam shrine will be relocated” – Borneo post, 23 March 2017 “Gazette Bongkissam shrine as historical site” - Borneo Post. -

The Perak Development Experience: the Way Forward

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences December 2013, Vol. 3, No. 12 ISSN: 2222-6990 The Perak Development Experience: The Way Forward Azham Md. Ali Department of Accounting and Finance, Faculty of Management and Economics Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i12/437 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i12/437 Speech for the Menteri Besar of Perak the Right Honourable Dato’ Seri DiRaja Dr Zambry bin Abd Kadir to be delivered on the occasion of Pangkor International Development Dialogue (PIDD) 2012 I9-21 November 2012 at Impiana Hotel, Ipoh Perak Darul Ridzuan Brothers and Sisters, Allow me to briefly mention to you some of the more important stuff that we have implemented in the last couple of years before we move on to others areas including the one on “The Way Forward” which I think that you are most interested to hear about. Under the so called Perak Amanjaya Development Plan, some of the things that we have tried to do are the same things that I believe many others here are concerned about: first, balanced development and economic distribution between the urban and rural areas by focusing on developing small towns; second, poverty eradication regardless of race or religion so that no one remains on the fringes of society or is left behind economically; and, third, youth empowerment. Under the first one, the state identifies viable small- and medium-size companies which can operate from small towns. These companies are to be working closely with the state government to boost the economy of the respective areas. -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

Contamination of Soils with Toxocara Eggs in Several Playgrounds of Ipoh, Perak

MALAYSIAN JOURNAL OF VETERINARY RESEARCH pages 74-82 • VOLUME 9 NO. 2 JULY 2018 CONTAMINATION OF SOILS WITH TOXOCARA EGGS IN SEVERAL PLAYGROUNDS OF IPOH, PERAK DEBBRA M.1, ZARY S.2, ERWANAS A. I.1, AZIMA LAILI H.1, NURULAINI R.1, ADNAN M.1 AND AZIZAH D.1 1 Parasitology and Haematology Section, Veterinary Research Institute, Jalan Sultan Azlan Shah, Ipoh, Perak, Malaysia. 2 Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Pulau Pinang, Malaysia * Corresponding author: [email protected]. ABSTRACT. Toxocariasis is an important INTRODUCTION cosmopolitan zoonotic disease mainly caused by Toxocara spp., a type of soil- According to Taylor et al. (2016), Toxocara transmitted helminth (STH) on cats and spp. is a group of parasitic STH classified dogs. In this study, 80 soil samples were under the family of Ascarididae and genus of taken from four public playgrounds and six Toxocara. Ascaridoids are among the largest neighbourhood playgrounds in Ipoh, Perak nematodes that affects many vertebrates between October and December 2016 to (mostly the domestic animals) as the adult determine the status of soil contamination stage can cause intestinal unthriftiness to with the eggs of Toxocara spp. Results young animals while their migratory larval showed that 32.5% from the total soil stage can cause pathological consequences. samples were positive with Toxocara spp. Both stages have socio-economic and eggs. Overall, five out of ten of the sampling veterinary significance (Li et al., 2006; Taylor sites were contaminated with Toxocara spp. et al., 2016). eggs. Besides that, the relationship between Toxocariasis (Toxocara infection) is the soil condition and the occurrence of listed as one of the five neglected parasitic the Toxocara spp. -

GGAM #KITAJAGAKITA Girl Guide Association Malaysia Covid-19 Responses Karling, Ejin, Sharrada, Jillian

G G A M C O V I D R E S P O N S E S : P H A S E 1 P A G E 1 GGAM #KITAJAGAKITA Girl Guide Association Malaysia Covid-19 Responses Karling, Ejin, Sharrada, Jillian #KitaJagaKita which means we take care of each other, regardless of race, religion, beliefs and social status. SUPPORTING OUR FRONTLINERS Malaysia has entered its eighth week under the Movement Control Order (MCO). While some of us are able to stay at home comfortably in an effort to flatten the curve and break the chain, there are many others struggling to make ends meet as industries are put on hold by the MCO. Malaysians have come together as one holding on strongly to #KitaJagaKita. Recognising the need to reach out to those in need, the Girl Guides Association Malaysia (GGAM) has been doing its part to lessen the burden of the pandemic to our community. 200 units of foldable beds contributed by GGAM for doctors and nurses. G G A M C O V I D R E S P O N S E S : P H A S E 1 P A G E 2 FACE MASKS WERE GENEROUSLY DONATED BY KEDAH, NEGERI SEMBILAN BRANCH AND OPEN COMPANY KEDAH BRANCH SOURCED OUT HAND SANITIZERS INNOVATE AND IMPROVISE Hospitals were facing a shortage with their equipment and the markets were running low on stock as well. GGAM branches started venturing into manufacturing their own equipments for these hospitals. SABAH, SARAWAK AND PAHANG BRANCH STARTED TO MAKE AND DISTRIBUTE FACE SHIELDS TO KEEP UP WITH THE HOSPITALS DEMAND G G A M C O V I D R E S P O N S E S : P H A S E 1 P A G E 3 TERENGGANU BRANCH DONATED PPE SUITS TO HOSPITALS IN NEED PAHANG BRANCH WORKING ON THE SHOE COVER AND HEAD COVER AS PART OF THE PPE. -

Daerah Kerian 2035

Ringkasan Eksekutif DRAF RANCANGAN TEMPATAN DAERAH KERIAN 2035 KANDUNGAN Ringkasan Eksekutif DRAF RANCANGAN TEMPATAN DAERAH KERIAN 2035 Keperluan Dan Proses Penyediaan Rancangan Tempatan Profil Daerah Kerian Penemuan Utama Guna Tanah Semasa Daerah Kerian 2018 Kerangka dan Teras Pembangunan Daerah Kerian Cadangan Konsep Pembangunan Daerah Kerian Guna Tanah Cadangan Daerah Kerian 2035 Teras 1: Pertumbuhan Ekonomi Dinamik dan Berdaya saing Teras 2: Pembangunan Fizikal Mampan dan Reka Bentuk Persekitaran Menarik Teras 3: Kelestarian Alam Sekitar dan Infrastruktur Efisien Teras 4: Pembangunan Komuniti Sejahtera Teras 5: Urus Tadbir Cekap dan Mesra Rakyat KEPERLUAN PENYEDIAAN RANCANGAN TEMPATAN Menggantikan Rancangan Tempatan Daerah Kerian 2020 Yang Akan Tamat Pada Menyelaraskan Tahun 2020 susun atur tanah- tanah yang terletak Menyelaraskan bersempadan perancangan di Daerah dengan lot-lot yang Kerian selaras dengan Draf telah dibangunkan 01 Rancangan Struktur Negeri Perak 2040 08 02 Memperincikan klasifikasi kegunaan tanah (Kelas Mengenal pasti kawasan Kegunaan Tanah) 07 yang sesuai untuk dan densiti dimajukan serta corak pembangunan serta pembangunan yang akan mengukuhkan dilaksanakan syarat-syarat 03 pembangunan 04 06 Merangka semula Membantu Pihak sistem perparitan bagi Berkuasa Perancang mengatasi isu banjir di Tempatan (PBPT) dalam kawasan potensi banjir 05 menyelaras di bawah pentadbiran pembangunan dan Majlis Daerah Kerian Meminda zon guna kawalan perancangan tanah berdasarkan kelulusan Tukar Syarat Tanah, Kebenaran Merancang dan pembangunan