Old Catholic Communion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archeacon of Gibraltar and Archdeacon of Italy and Malta

The Bishop in Europe: The Right Reverend Dr. Robert Innes The Suffragan Bishop in Europe: The Right Reverend David Hamid ARCHEACON OF GIBRALTAR AND ARCHDEACON OF ITALY AND MALTA Statement from the Bishops The Diocese in Europe is the 42nd Diocese of the Church of England. We are by far the biggest in terms of land area, as we range across over 42 countries in a territory approximately matching that covered by the Council of Europe, as well as Morocco. We currently attract unprecedented interest within the Church of England, as we are that part of the Church that specifically maintains links with continental Europe at a time of political uncertainty between the UK and the rest of Europe. Along with that, we have been in the fortunate position of being able to recruit some very high calibre lay and ordained staff. To help oversee our vast territory we have two bishops, the Diocesan Bishop Robert Innes who is based in Brussels, and the Suffragan Bishop David Hamid who is based in London. We have a diocesan office within Church House Westminster. We maintain strong connections with staff in the National Church Institutions. Importantly, and unlike English dioceses, our chaplaincies pay for their own clergy, and the diocese has relatively few support staff. Each appointment matters greatly to us. The diocesan strategy was formulated and approved over the course of 2015. We are emphasising our commitment to building up congregational life, our part in the re- evangelisation of the continent; our commitment to reconciliation at every level; and our particular role in serving the poor, the marginalised and the migrant. -

ACHS Newsletter—May 2018

ANGLO-CATHOLIC HISTORY SOCIETY Newsletter—May 2018 Members outside the west door of St John of Jerusalem with Fr Steve Gayle, the curate, who made us so welcome, at the end of our walk around some of the churches of Hackney www.achs.org.uk CHAIRMAN’S NOTES much else) known especially for his work on the ideas and influence of the political philosopher and It is with great pleasure that I can announce, Mirfield monk J. Neville Figgis, whose centenary of following the sad death of our President Bishop death occurs next year. Geoffrey Rowell, that Bishop Rowan Williams Our paths crossed from time to time, most (Baron Williams of Oystermouth) has kindly agreed recently in October 2016 when I met him at the to become our new President. University of the South in Tennessee, where he was giving the Du Bose Lectures. The post of President isn’t one that requires much in the day to day running of our Society, but +Rowan has agreed to give an Inaugural Lecture. I hoped this might be next year but such is his diary it will be Monday 27th January 2020, the subject to be announced. I have begun planning the 2019 programme and can announce that on Monday 28th January our speaker will be Dr Clemence Schultze, the Chair of the Charlotte Yonge Fellowship. Charlotte M. Yonge (1823-1901) has been called “the novelist of the Oxford Movement”. She lived all her life in Otterbourne, near Winchester, not far from her spiritual mentor John Keble who, at Hursley, was a near neighbour. -

No.48 Winter 2010

THE E UROP E AN A NGLICAN B ISHOP ’ S VI E WS ON PAPAL VISIT F ROM A TV STUDIO Y OUNG ARTIST ’ S S E ASONAL GI F T C HRISTMAS CARD D E SIGNS L I fe SAV E R IN F LOR E NC E A WARD F OR PARAM E DIC A NGOLAN ADV E NTUR E G OSP E L SHARING IN L UANDA C OP E NHAG E N TW E LV E MONTHS ON E NVIRONM E NTAL R E VI E W FREE N o . 4 8 WI nter 2 0 1 0 E N COU R AGI N G Y O U N G 2 T AL ent S I N N A P L E S THE E UROP E AN A NGLICA N I T ’ S ALL A B OUT HIGH SP ee D The Bishop of Gibraltar in Europe The Rt Revd Geoffrey Rowell Bishop’s Lodge, Church Road, Worth, Crawley RH10 7RT Tel: +44 (0) 1293 883051 COMMUNICATION Fax: +44 (0) 1293 884479 Email: [email protected] The Suffragan Bishop in Europe The Rt Revd David Hamid Postal address: Diocesan Office Tel: +44 (0) 207 898 1160 Email: [email protected] The Diocesan Office 14 Tufton Street, London, SW1P 3QZ Tel: +44 (0) 207 898 1155 Fax: +44 (0) 207 898 1166 Email: diocesan.office@europe. c-of-e.org.uk Diocesan Secretary I am an unreformed fan of rail travel and This edition of the European Anglican Mr Adrian Mumford so it did not take me long to accept a includes personal stories – of a Good Assistant Diocesan Secretary challenge from my local English newspaper Samaritan´s life saving skills in Italy, of a Mrs Jeanne French in Spain to try the journey from London young boy´s enthusiasm for art which has Finance Officer to Tarragona by train in a day. -

Shankland Searches Gibraltar for Final Norm by IM San Shankland February 7, 2010

Shankland Searches Gibraltar for Final Norm by IM San Shankland February 7, 2010 It feels like it was just yesterday that I was hurrying through Staples to try to find some European power converters before I had to go to the airport to make the lengthy trip to Gibraltar, the home of the 2010 Gibtelecom Masters tournament. Just for fun, I put on a fake European accent when I asked for help in finding them, and I must say I was treated better than I normally would have been. The cashier was particularly friendly- while she was ringing up the charges she was telling me she never gets to meet people from Europe. I was very tempted to at that point drop the whole accent thing, but I thought that would prolong the conversation and NM and US Chess League Vice-president Arun Sharma IM Sam Shankland Photo courtesy Monroi.com was back home waiting to drive me to the train station. Some 22 hours later, I landed in Gibraltar after one of the most stress-free travel experiences I’ve ever had. The 10-hour flight from San Francisco to London was probably my best ever, because for some reason, none of the seats adjacent to me were taken (geez, do I smell THAT BAD??) so while the rest of the plane was packed, I got to lie down and get some sleep. Once I arrived in Gibraltar, things started to get strange. The room key to my hotel was about a foot long, and I was informed that when I leave the hotel I must leave it at the front desk and then pick it up again when I got back. -

Anglicans and Old Catholics Serving in Europe 2019 Report

Anglicans and Old Catholics Serving in Europe A Report of the Anglican–Old Catholic International Coordinating Council 2013–2019 to the Anglican Consultative Council 17 Hong Kong April/ May 2019 and the International Bishops’ Conference, Lublin June 2019 AOCICC Amersfoort 2013 Kilkenny 2014 Contents Preface by the Co-Chairs 5 Executive Summary 7 Members of the Council 2013–2019 8 1 Introduction 9 a Bonn 1931: Belonging together 9 b The context of Europe: Walking together in an evolving Europe 10 c The context of the ecumenical movement 11 2 The significance of the Bonn Agreement today 13 a An Anglican Communion perspective 13 b An Old Catholic perspective 14 3 The AOCICC’s story 1998–2019 16 4 Outworking of the AOCICC mandate 19 a The AOCICC’s work achieved 2013–2019 19 b. Mandate i: ‘To continue to explore the nature and meaning of our communion’ 20 Mandate ii: ‘To promote knowledge of our churches and their relationship’ 22 Mandate iii: ‘To assist the annual meeting of Old Catholic and Anglican bishops’ 27 Mandate iv: ‘To explore the possibility of establishing a representative body’ 30 Mandate v: ‘To advise on the establishment of appropriate instruments’ 32 Mandate vi: ‘To review the consistency of ecumenical agreements’ 34 5 Proposals for the next AOCICC mandate 36 For submission to ACC-17, 2019 36 Anglican–Old Catholic Relations 36 Appendix 1 – Communiqués 37 Appendix 2 45 Willibrord Declaration 2017 45 Endnotes 47 3 Zurich 2015 Ghent 2016 Preface by the Co-Chairs To the Anglican Consultative Council (ACC) and the International Bishops’ Conference of Old Catholic Churches (IBC). -

A Report of the House of Bishops' Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church Ho

Women Bishops in the Church of England? A report of the House of Bishops’ Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church House Publishing Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3NZ Tel: 020 7898 1451 Fax: 020 7989 1449 ISBN 0 7151 4037 X GS 1557 Printed in England by The Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Published 2004 for the House of Bishops of the General Synod of the Church of England by Church House Publishing. Copyright © The Archbishops’ Council 2004 Index copyright © Meg Davies 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored or transmitted by any means or in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written permission, which should be sought from the Copyright Administrator, The Archbishops’ Council, Church of England, Church House, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3NZ. Email: [email protected]. The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, and are used by permission. All rights reserved. Contents Membership of the Working Party vii Prefaceix Foreword by the Chair of the Working Party xi 1. Introduction 1 2. Episcopacy in the Church of England 8 3. How should we approach the issue of whether women 66 should be ordained as bishops? 4. The development of women’s ministry 114 in the Church of England 5. Can it be right in principle for women to be consecrated as 136 bishops in the Church of England? 6. -

The Krk Diocese

THE KRK DIOCESE THE ISLES SHALL WAIT FOR HIS TEACHINGS O I R E T S I IN M T I E N IO ORAT FOREWORD The centuries-long presence of Christianity on the islands of the Krk Diocese is deeply rooted in the life and culture of its population, which has been subject to a succession of various social orders during the course of history. Until the year 1828, there were three dioceses within this territory: Krk, Osor and Rab. The presence of a bishop and his relationship with the people had a strong impact upon spiritual formation and identity. The pas- tors of the small dioceses of the Kvarner Islands demonstrated magna- nimity and openness of spirit toward the beautiful and modern, while at the same time listening to the “pulse” of the people, incorporating their language in worship. The beauty of handwritten and illuminated Glagolitic missals, psalters and antiphonals greatly enriched the corpus of liturgical literature traditionally written in Latin. Christian culture, both spiritual and material, is reflected here in the arts of painting, architecture, literature, poetry and music. This is a Church distinguished by its priests and religious, especially the Benedictines and Franciscans, including those with the reputation of saintliness, who have played exceptional historical roles in the raising and fostering of national consciousness, enhancement of the quality of life, education in moral principles, and the creation and safeguarding of the cultural heritage. These values provided a firm foundation for assuring the survival of this nation under changing conditions, not infrequently im- posed by fire and sword. -

Bishop's Statement

Suffragan Bishop: The Right Reverend David Hamid A Statement from Bishop David on St Alban’s Church, Copenhagen. A Supplement to the Chaplaincy Profile - 15 August 2008 Archdeaconry and Diocese St Alban’s Copenhagen is part of the Archdeaconry of Germany and Northern Europe, and the Deanery of the Nordic Baltic States, within the Diocese in Europe. The chaplain is required to participate, along with the lay representatives, in the life of the Archdeaconry and Deanery. The synodical life has for several years focussed around the Deanery which meets for about 3 days residentially each year. (The position of Archdeacon of Germany and Northern Europe is presently vacant). The Revd Nicholas Howe, the chaplain in Stockholm, is the Area Dean. Each archdeaconry in the diocese has a lead bishop, either the Diocesan Bishop or the Suffragan Bishop, to provide pastoral care for the clergy and congregations, oversight of routine vacancy and appointment processes, care of title curates, consultation with mission agencies, strategic direction, mission planning and new initiatives. The Suffragan Bishop in Europe is the lead bishop for the Archdeaconry of Germany and Northern Europe. Ecumenical and Inter-Church Relations The Diocese in Europe has a distinct ecumenical vocation and our priests have a key role in carrying out this vocation. The diocesan guidelines and regulations state that the Diocese in Europe seeks “to minister and engage in mission in partnership with other Churches especially the historic Churches of the countries in which we live”. The major Church partner in Denmark is the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Denmark. Although not a signatory to the Porvoo Common Statement, this Church has observer status at Porvoo meetings. -

General Synod

GS 1708-09Y GENERAL SYNOD DRAFT BISHOPS AND PRIESTS (CONSECRATION AND ORDINATION OF WOMEN) MEASURE DRAFT AMENDING CANON No. 30 ILLUSTRATIVE DRAFT CODE OF PRACTICE REVISION COMMITTEE Chair: The Ven Clive Mansell (Rochester) Ex officio members (Steering Committee): The Rt Revd Nigel McCulloch, (Bishop of Manchester) (Chair) The Very Revd Vivienne Faull (Dean of Leicester) Dr Paula Gooder (Birmingham) The Ven Ian Jagger (Durham) (from 26 September 2009) The Ven Alastair Magowan (Salisbury) (until 25 September 2009) The Revd Canon Anne Stevens (Southwark) Mrs Margaret Swinson (Liverpool) Mr Geoffrey Tattersall QC (Manchester) The Rt Revd Trevor Willmott (Bishop of Dover) Appointed members: Mrs April Alexander (Southwark) Mrs Lorna Ashworth (Chichester) The Revd Dr Jonathan Baker (Oxford) The Rt Revd Pete Broadbent (Southern Suffragans) The Ven Christine Hardman (Southwark) The Revd Canon Dr Alan Hargrave (Ely) The Rt Revd Martyn Jarrett (Northern Suffragans) The Revd Canon Simon Killwick (Manchester) The Revd Angus MacLeay (Rochester) Mrs Caroline Spencer (Canterbury) Consultants: Diocesan Secretaries: Mrs Jane Easton (Diocesan Secretary of Leicester) Diocesan Registrars: Mr Lionel Lennox (Diocesan Registrar of York) The Revd Canon John Rees (Diocesan Registrar of Oxford) 1 CONTENTS Page Number Glossary 3 Preface 5 Part 1: How the journey began 8 Part 2: How the journey unfolded 15 Part 3: How the journey was completed – the Committee‟s clause by clause consideration of the draft legislation A. The draft Bishops and Priests (Consecration and Ordination of Women) Measure 32 B. Draft Amending Canon No. 30 69 Part 4: Signposts for what lies ahead 77 Appendix 1: Proposals for amendment and submissions 83 Appendix 2: Summary of proposals and submissions received which raised points of substance and the Committee‟s consideration thereof Part 1. -

Brian Knight

STRATEGY, MISSION AND PEOPLE IN A RURAL DIOCESE A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF THE DIOCESE OF GLOUCESTER 1863-1923 BRIAN KNIGHT A thesis submitted to the University of Gloucestershire in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities August, 2002 11 Strategy, Mission and People in a Rural Diocese A critical examination of the Diocese of Gloucester 1863-1923 Abstract A study of the relationship between the people of Gloucestershire and the Church of England diocese of Gloucester under two bishops, Charles John Ellicott and Edgar Charles Sumner Gibson who presided over a mainly rural diocese, predominantly of small parishes with populations under 2,000. Drawing largely on reports and statistics from individual parishes, the study recalls an era in which the class structure was a dominant factor. The framework of the diocese, with its small villages, many of them presided over by a squire, helped to perpetuate a quasi-feudal system which made sharp distinctions between leaders and led. It is shown how for most of this period Church leaders deliberately chose to ally themselves with the power and influence of the wealthy and cultured levels of society and ostensibly to further their interests. The consequence was that they failed to understand and alienated a large proportion of the lower orders, who were effectively excluded from any involvement in the Church's affairs. Both bishops over-estimated the influence of the Church on the general population but with the twentieth century came the realisation that the working man and women of all classes had qualities which could be adapted to the Church's service and a wider lay involvement was strongly encouraged. -

Autumn 2014 2 Consecration in Canterbury

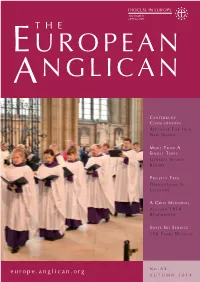

THE E UROP E AN A NGLICAN C ANT E RBURY C ONS E CRATION A PPLAUS E F OR O UR N E W B ISHOP M OR E T HAN A S INGL E T OPIC G E N E RAL S YNOD R E PORT P RI E STLY T RIO O RDINATIONS I N C OLOGN E A G RI M M em ORIAL A UTU M N 1 9 1 4 R emem B E R E D S WISS S KI S E RVIC E 1 5 0 Y E ARS W ITN E SS europe.anglican.org No.63 AUTUMN 2014 2 CONSECRATION IN CANTERBURY THE E UROP E AN E UROP E AN , E CU me NICAL AND E NCOURAGING A NGLICA N B ISHOP R OB E RT ’S The Bishop of Gibraltar in Europe The Rt Rev Robert Innes F IRST ST E PS The Suffragan Bishop in Europe The Rt Rev David Hamid Postal address: Diocesan Office Tel: +44 (0) 207 898 1160 Email: [email protected] The Diocesan Office 14 Tufton Street, London, SW1P 3QZ Tel: +44 (0) 207 898 1155 Fax: +44 (0) 207 898 1166 Email: [email protected] Diocesan Secretary Mr Adrian Mumford Appointments Secretary Miss Catherine Jackson Finance Secretary Mr Nick Wraight Diocesan Website www.europe.anglican.org Editor and Diocesan Communications Officer The Rev Paul Needle and boys voices together, and with the Postal address: Diocesan Office backing of trumpeters they did justice to Email: the old German hymn Praise to the Lord, [email protected] the Almighty, the King of creation. -

Solemn Requiem for Bishop Geoffrey Rowell Chichester Cathedral, 5 July 2017

Solemn Requiem for Bishop Geoffrey Rowell Chichester Cathedral, 5 July 2017 Sermon by the Rt Revd Dr Rowan Williams, Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge Sometime in 1967 or 1968 a friend was discussing with Austin Farrer some of the new fashions in theology – notably, the idea that perhaps God was dead. Farrer, theological hero for Geoffrey as for many here today, replied, ‘The test is: do they believe in a future life? If people don’t believe in a future life, I can’t believe they believe in God.’ To some people’s ears, that comment might grate. Surely that would be back to the days of ‘pie in the sky’ fantasies, in which people were so interested in what happened after death that they gave themselves an alibi for the meantime? But hear those words again in the context of the Gospel we have just listened to: ‘I am the resurrection, and the life’, says Jesus. We believe in a future life because we believe in that kind of God. We believe that, if God is God, we shall not fall into nothingness, and that, if Jesus is God, it is his hands that will hold us in and through the greatest loss we can imagine. To believe in God is to believe in God’s faithfulness, and to believe in God’s faithfulness is to believe in the resurrection. Geoffrey certainly knew a great deal about the history of belief in the afterlife. His book Hell and the Victorians remains a classic of its kind – a book which not only covers shifts in intellectual fortunes, but also reflects on the impact on wider human culture of the loss of belief in regard to life everlasting.