The Potential and Challenges for Online Freelancing and Microwork in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural Work of Microwork

Article new media & society 0(0) 1–21 © THe AutHor(s) 2013 The cultural work of Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uK/journalsPermissions.nav microwork DOI: 10.1177/1461444813511926 nms.sagepub.com Lilly Irani UC San Diego, USA Abstract This paper focuses on Amazon MecHanical TurK as an emblematic case of microworK crowdsourcing. New media studies researcH on crowdsourcing Has focused on questions of fair treatment of worKers, creativity of microlabor, and the ethics of microwork. THis paper argues tHat tHe divisions of labors and mediations of software interfaces made possible by sociotecHnical systems of microworK also do cultural worK in new media production. This paper draws from infrastructure studies and feminist science and tecHnology studies to examine Amazon MecHanical TurK and tHe Kinds of worKers and employers produced througH the practices associated with the system. Crowdsourcing systems, we will show, are mechanisms not only for getting tasks done, but for producing difference between “innovative” laborers and menial laborers and ameliorating resulting tensions in cultures of new media production. Keywords cloud computing, crowdsourcing, entrepreneurialism, gender, infrastructure, invisible worK, labor, peer production, subjectivities Introduction You’ve heard of software-as-a-service. Well this is human-as-a-service. – Jeff Bezos announcing Amazon Mechanical Turk in 2006 Corresponding author[AQ: 1] Lilly Irani, Department of Communication, UC San Diego, 9500 Gilman Dr. La Jolla, CA 92093-0503, USA. Email: [email protected] 2 new media & society 0(0) In 2006, CEO of Amazon Jeff Bezos addressed an auditorium of technologists, reporters, and professors had assembled at MIT to hear “what’s next,” informing investments of capital and research agendas. -

Microworkers’ Emerging Bonds of Attachment in A

Paper accepted for publication in Work, Employment and Society, December 2019 ‘If he just knew who we were’: Microworkers’ emerging bonds of attachment in a fragmented employment relationship Niki Panteli Royal Holloway, University of London Andriana Rapti University of Nicosia, Cyprus Dora Scholarios University of Strathclyde, Glasgow 1 Abstract Using the lens of attachment, we explore microworkers’ views of their employment relationship. Microwork comprises short-term, task-focused exchanges with large numbers of end-users (requesters), implying transitory and transactional relationships. Other key parties, however, include the platform which digitally meditates worker-requester relationships and the online microworker community. We explore the nature of attachment with these parties and the implications for microworkers’ employment experiences. Using data from a workers’ campaign directed at Amazon Mechanical Turk and CEO Jeff Bezos, we demonstrate multiple, dynamic bonds, primarily, acquiescence and instrumental bonds towards requesters and the platform, and identification with the online community. Microworkers also expressed dedication towards the platform. We consider how attachment buffers the exploitative employment relationship and how community bonds mobilise collective worker voice. Keywords: attachment, bonds, digital labour, digital platform, employment relationship, gig economy, gig work, identification, microworkers, platform labour, work attachment, worker voice Corresponding Author: Dora Scholarios, Department of Work, Employment & Organisation, Strathclyde Business School, 199 Cathedral Street, Glasgow, G4 8QU. email: [email protected] 2 Introduction On-demand digital labour is a pervasive aspect of employment in today’s gig economy (Howcroft and Bergvall-Kareborn, 2018; Wood et al., 2018a). This article focuses on one type of digital labour – online task crowdwork - which involves paid micro-tasks, or Human Intelligence Tasks (HITs), disseminated through digital platforms and requested by either individuals or companies. -

Alibaba: Entrepreneurial Growth and Global Expansion in B2B/B2C Markets

JIntEntrep DOI 10.1007/s10843-017-0207-2 Alibaba: Entrepreneurial growth and global expansion in B2B/B2C markets Syed Tariq Anwar 1 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2017 Abstract The purpose of this case-based research is to analyze and discuss Alibaba Group (hereafter Alibaba) and its entrepreneurial growth and global expansion in B2B/ B2C markets. The paper uses company and industry-specific data and surveys to analyze a fast growing Chinese B2B/B2C firm and its internationalization and expan- sion in global markets. Findings of the work reveal that in a short time, Alibaba has become a major entrepreneurial icon and global player and continues to grow world- wide because of its well-planned business initiatives and B2B/B2C-based business models. The paper also provides implications in the area of international entrepreneur- ship and its related areas. International entrepreneurs need to learn from Alibaba’sfast growing business model and dynamic growth because of its competitive platforms and Web-based strategies which helped the company to target small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in global markets. Within the areas of international entrepreneurship and international business, the paper also provides discussion which deals with the changing e-commerce industry and its future growth and developments. El objetivo de esta investigación basada en casos de negocios es analizar y discutir el Grupo Alibaba (de aquí en adelante Alibaba) y su crecimiento empresarial y la expansión global en mercados de B2B/B2C. El ensayo utiliza estadísticas y encuestas específicas a la compañía e industria para analizar una empresa china B2B/B2C y su internalización y expansión en los mercados globales. -

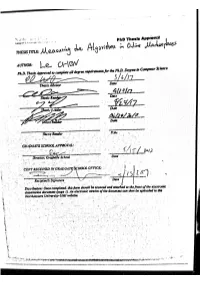

Measuring Algorithms in Online Marketplaces

Measuring Algorithms in Online Marketplaces A Dissertation Presented by Le Chen to The College of Computer and Information Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts May 2017 Dedicated to my courageous and lovely wife. i Contents List of Figures v List of Tables viii Acknowledgments x Abstract of the Dissertation xi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Uber . 2 1.2 Amazon Marketplace . 4 1.3 Hiring Sites . 7 1.4 Outline . 9 2 Related Work 10 2.1 Online Marketplaces . 10 2.1.1 Price Competition . 10 2.1.2 Fraud and Privacy . 11 2.2 Hiring Discrimination . 11 2.2.1 The Importance of Rank . 12 2.3 Auditing Algorithms . 13 2.3.1 Filter Bubbles . 13 2.3.2 Price Discrimination . 14 2.3.3 Gender and Racial Discrimination . 14 2.3.4 Privacy and Transparency . 15 3 Uber’s Surge Pricing Algorithm 16 3.1 Background . 16 3.2 Methodology . 18 3.2.1 Selecting Locations . 19 3.2.2 The Uber API . 19 3.2.3 Collecting Data from the Uber App . 19 3.2.4 Calibration . 22 3.2.5 Validation . 24 ii 3.3 Analysis . 25 3.3.1 Data Collection and Cleaning . 26 3.3.2 Dynamics Over Time . 27 3.3.3 Spatial Dynamics and EWT . 29 3.4 Surge Pricing . 30 3.4.1 The Cost of Surges . 31 3.4.2 Surge Duration and Updates . 32 3.4.3 Surge Areas . 33 3.4.4 Algorithm Features and Forecasting . -

Subcontracting Microwork CHI 2017 Submission

Subcontracting Microwork Meredith Ringel Morris1, Jeffrey P. Bigham2, Robin Brewer3, Jonathan Bragg4, Anand Kulkarni5, Jessie Li2, and Saiph Savage6 1Microsoft Research, Redmond, WA, USA 2Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA 3Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA 4University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 5University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA 6West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA [email protected], {bigham, jessieli}@cs.cmu.edu, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT scientific enterprises [10, 11], and community or volunteer Mainstream crowdwork platforms treat microtasks as ventures [5]. Mainstream crowdwork platforms treat indivisible units; however, in this article, we propose that microtasks (also called human intelligence tasks or HITs) as there is value in re-examining this assumption. We argue that indivisible units; however, we propose that there is value in crowdwork platforms can improve their value proposition re-examining this assumption. We argue that crowdwork for all stakeholders by supporting subcontracting within platforms can improve their value proposition for all microtasks. After describing the value proposition of stakeholders by supporting subcontracting within subcontracting, we then define three models for microtask microtasks, i.e. outsourcing one or more aspects of a subcontracting: real-time assistance, task management, and microtask to additional workers. task improvement, and reflect on potential use cases -

2020 Annual Report Contents

Real world AI 2020 Annual Report Contents 2 What we do 3 Why we do it 4 Making AI work in the real world 10 Capturing the market opportunity 12 2020 highlights 14 Chairman’s message 16 CEO’s message 18 Our competitive advantage 19 Our strategic priorities 20 How we create value 22 Global crowd Artificial 24 Appen employees 26 Technology, processes, systems 28 Customer and brand 30 Financial 32 Social and environment intelligence... 36 Identifying and managing risk 44 Our approach to governance 46 Board of Directors 48 Executive Team Appen makes AI work in the real world by 50 Directors’ report 58 Remuneration report delivering high-quality training data at scale. 72 Lead auditor’s independence declaration Training data is used to build and continuously 73 Financial report 128 Directors’ declaration improve the world’s most innovative AI 129 Independent auditor’s report enhanced systems and services. 133 Additional information 136 Corporate directory Our clients include the world’s largest technology companies, global leaders in automotive, financial services, retail and healthcare, and government agencies. ...informed by Appen. About this report We have used the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) <IR> Framework and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) Standards to guide our disclosures on how Appen creates value and which topics are financially material to our business. Appen Limited ABN 60 138 878 298 Appen 2020 Annual Report 1 Contents 2 What we do 3 Why we do it 4 Making AI work in the real world 10 Capturing the market opportunity 12 2020 highlights 14 Chairman’s message 16 CEO’s message 18 Our competitive advantage 19 Our strategic priorities 20 How we create value 22 Global crowd Artificial 24 Appen employees 26 Technology, processes, systems 28 Customer and brand 30 Financial 32 Social and environment intelligence.. -

Design Activism for Minimum Wage Crowd Work

Design Activism for Minimum Wage Crowd Work Akash Mankar Riddhi J. Shah Matthew Lease National Instruments Rackspace School of Information Austin, TX USA Austin, TX USA University of Texas at Austin [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract required to compensate workers according to local mini- mum wage laws. Would any Requesters support such a pol- Entry-level crowd work is often reported to pay less than min- icy? Would any workers support being blocked from tasks imum wage. While this may be appropriate or even necessary, due to various legal, economic, and pragmatic factors, some that did not meet this wage restriction in their local region? Requesters and workers continue to question this status quo. Would workers in different regions have different views? To promote further discussion on the issue, we survey Re- As inspiration, Turkopticon (Irani and Silberman 2013)’s questers and workers whether they would support restricting design activism both provided functional enhancements on tasks to require minimum wage pay. As a form of design ac- AMT, helping mitigate power disparities, but also provoked tivism, we confronted workers with this dilemma directly by discussion and disrupt common rhetoric of technocentric op- posting a dummy Mechanical Turk task which told them that timism surrounding crowd-powered systems. In this work, they could not work on it because it paid less than their local we survey workers and Requesters, and to be more provoca- minimum wage, and we invited their feedback. Strikingly, for tive, we created a dummy Mechanical Turk task in which those workers expressing an opinion, two-thirds of Indians workers were told after accepting the task that they could favored the policy while two-thirds of Americans opposed it. -

How Many People Microwork in France? Estimating the Size of a New Labor Force Clément Le Ludec, Paola Tubaro, Antonio Casilli

How many people microwork in France? Estimating the size of a new labor force Clément Le Ludec, Paola Tubaro, Antonio Casilli To cite this version: Clément Le Ludec, Paola Tubaro, Antonio Casilli. How many people microwork in France? Estimating the size of a new labor force. 2019. hal-02012731 HAL Id: hal-02012731 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02012731 Preprint submitted on 16 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. How many people microwork in France? Estimating the size of a new labor force CLÉMENT LE LUDEC, MSH Paris Saclay, France PAOLA TUBARO, National Center of Scientific Research (CNRS), France ANTONIO A. CASILLI, Telecom ParisTech, France Microwork platforms allocate fragmented tasks to crowds of providers with This novel organization of AI-driven automation in contemporary remunerations as low as few cents. Instrumental to the development of industries does not "replace" human jobs but makes human contri- today’s artificial intelligence, these micro-tasks push to the extreme the bution to productive processes largely inconspicuous. It supports logic of casualization already observed in "uberized" workers. The present technologies where they fail, and yet it is not a selling point that article uses the results of the DiPLab study to estimate the number of people companies leverage to attract and retain large userbases. -

The Investment Case for Online Retail

The Investment Case for Online Retail Executive Summary Online retail has permanently disrupted the traditional brick-and-mortar store retail landscape as “clicks” have replaced “bricks.” According to research firm eMarketer, global ecommerce is expected to approach $5 trillion this year1, as online retailers have had fertile ground to grow their business in this new era of contactless shopping. In the United States, ecommerce sales grew to $795 billion in 2020, a 32.4% increase over 2019, versus previous forecasts of 18% growth.2 The global coronavirus pandemic has accelerated the pace of ecommerce growth in 2020, propelling online sales to levels not previously expected until 2022—helping existing online retailers expand their dominance in retail. Value-added features such as competitive pricing, shopping convenience, greater product selection and rapid delivery options have solidified online commerce as a disruptive technology that is here to stay. Ever-increasing internet and mobile penetration is one of the key drivers contributing to this growth, enabling more consumers to shop online anywhere and anytime. New technological innovations in electronic payment, rapid delivery, artificial intelligence and voice-assisted shopping, as well as virtual and augmented reality continue to enhance the online shopping experience, further driving the expansion and growth of this investment theme. Additionally, due to the pandemic in 2020, digital commerce added new shoppers that had not previously shopped online, fueling new buying habits such as online grocery, which grew 43%.3 This trend has accelerated traditional retail’s woes, with 30 U.S. retailers having filed for bankruptcy in 2020, on the heels of 17 major retailer bankruptcies in 2019, pre-pandemic.4 Amid this marketplace evolution, online retail has become a transformational and dominant force in global retail. -

Request for Proposals For

REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS FOR: Online Marketplace Pilot Proposal Due: Monday, April 1, 2019 Due to: Aptim Government Solutions, LLC Wisconsin’s Focus on Energy Program Administrator Issued: March 1, 2019 Online Marketplace Pilot RFP Table of Contents Definitions ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. RFP Summary Information .................................................................................................................... 6 2. Proposal Checklist ................................................................................................................................. 7 3. Overview of Focus on Energy ................................................................................................................ 8 3.1. Governance Structure of Focus on Energy ................................................................................... 8 4. Program Information ............................................................................................................................ 9 4.1. Program Summary ........................................................................................................................ 9 4.2. Eligible Program Areas and Program Elements to Consider ......................................................... 9 4.2.1. Program Design ..................................................................................................................... 9 4.3. Program Priorities -

China's E-Tail Revolution: Online Shopping As a Catalyst for Growth

McKinsey Global Institute McKinsey Global Institute China’s e-tail revolution: Online e-tail revolution: shoppingChina’s as a catalyst for growth March 2013 China’s e-tail revolution: Online shopping as a catalyst for growth The McKinsey Global Institute The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, was established in 1990 to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. Our goal is to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth; natural resources; labor markets; the evolution of global financial markets; the economic impact of technology and innovation; and urbanization. Recent reports have assessed job creation, resource productivity, cities of the future, the economic impact of the Internet, and the future of manufacturing. MGI is led by two McKinsey & Company directors: Richard Dobbs and James Manyika. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, and Jaana Remes serve as MGI principals. Project teams are led by the MGI principals and a group of senior fellows, and include consultants from McKinsey & Company’s offices around the world. These teams draw on McKinsey & Company’s global network of partners and industry and management experts. -

Amazon's Next Frontier: Your City's Purchasing

Amazon’s Next Frontier: Your City’s Purchasing Amazon is changing the rules for how local governments buy goods — and putting cities, counties, and school districts at risk. By Olivia LaVecchia and Stacy Mitchell July 2018 About the Institute for Local Self-Reliance The Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) is a 44-year-old national nonprofit research and educational organization. ILSR’s mission is to provide innovative strategies, working models, and timely information to support strong, community rooted, environmentally sound, and equitable local economies. To this end, ILSR works with citizens, policymakers, and businesses to design systems, policies, and enterprises that meet local needs; to maximize human, material, natural, and financial resources; and to ensure that the benefits of these systems and resources accrue to all local citizens. More at www.ilsr.org. About the Authors Stacy Mitchell is co-director of ILSR and director of its Community-Scaled Economy Initiative. Her research and writing on the advantages of devolving economic power have influenced policymakers and helped guide grassroots strategies. She has authored two books, produced numerous reports, and written articles for national publications including Bloomberg Businessweek and The Nation. Contact her at [email protected] or on Twitter at @stacyfmitchell. Olivia LaVecchia is a senior researcher with ILSR’s Community-Scaled Economy Initiative, where her work focuses on building awareness and support for public policy tools that strengthen locally owned businesses and check concentrated power. She is the author of reports and articles that have For monthly reached wide audiences, spurred grassroots action, and influenced policy. updates on our Contact her at [email protected] or on Twitter at @olavecchia.