Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

NOTES Introduction 1. Robert Kagan to George Packer. Cited in Packer’s The Assassin’s Gate: America In Iraq (Faber and Faber, London, 2006): 38. 2. Stefan Halper and Jonathan Clarke, America Alone: The Neoconservatives and the Global Order (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004): 9. 3. Critiques of the war on terror and its origins include Gary Dorrien, Imperial Designs: Neoconservatism and the New Pax Americana (Routledge, New York and London, 2004); Francis Fukuyama, After the Neocons: America At the Crossroads (Profile Books, London, 2006); Ira Chernus, Monsters to Destroy: The Neoconservative War on Terror and Sin (Paradigm Publishers, Boulder, CO and London, 2006); and Jacob Heilbrunn, They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons (Doubleday, New York, 2008). 4. A report of the PNAC, Rebuilding America’s Defenses: Strategy, Forces and Resources for a New Century, September 2000: 76. URL: http:// www.newamericancentury.org/RebuildingAmericasDefenses.pdf (15 January 2009). 5. On the first generation on Cold War neoconservatives, which has been covered far more extensively than the second, see Gary Dorrien, The Neoconservative Mind: Politics, Culture and the War of Ideology (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1993); Peter Steinfels, The Neoconservatives: The Men Who Are Changing America’s Politics (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1979); Murray Friedman, The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2005); Murray Friedman ed. Commentary in American Life (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2005); Mark Gerson, The Neoconservative Vision: From the Cold War to the Culture Wars (Madison Books, Lanham MD; New York; Oxford, 1997); and Maria Ryan, “Neoconservative Intellectuals and the Limitations of Governing: The Reagan Administration and the Demise of the Cold War,” Comparative American Studies, Vol. -

Pets Are Popular with U.S. Presidents

Pets Are Popular With U.S. Presidents Most people have heard by now that President-elect Barack Obama promised his two daughters a puppy if he were elected president. Obama called choosing a dog a “major issue” for the new first family. It seems that pets have always been very popular with U.S. presidents. Only two of the 44 presidents -- Chester A. Arthur and Franklin Pierce -- left no record of having pets. Many presidents and their children had dogs and cats in the White House. President and Mrs. Bush have two dogs and a cat living with them -- the dogs are named Barney and Miss Beazley and the cat is India. But there have been many unusual presidential pets as well. President Calvin Coolidge may have had the most pets. NEWS WORD BOX He had a pygmy hippopotamus, six dogs, a bobcat, a goose, a donkey, a cat, two lion cubs, an antelope, and popular issue record wallaby a wallaby. President Herbert Hoover had several dogs pygmy hippopotamus and his son had two pet alligators, which sometimes took walks outside the White House. Caroline Kennedy, the daughter of President John F. Kennedy, had a pony named Macaroni. She would ride Macaroni around the White House grounds. Some pets also worked while at the White House. Pauline the cow was the last cow to live at the White House. She provided milk for President William Taft. To save money during World War I, President Woodrow Wilson brought in a flock of sheep to trim the White House lawn. The flock included a ram named Old Ike. -

White House Compliance with Committee Subpoenas Hearings

WHITE HOUSE COMPLIANCE WITH COMMITTEE SUBPOENAS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 6 AND 7, 1997 Serial No. 105–61 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform and Oversight ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 45–405 CC WASHINGTON : 1998 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Jan 31 2003 08:13 May 28, 2003 Jkt 085679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HEARINGS\45405 45405 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT DAN BURTON, Indiana, Chairman BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York HENRY A. WAXMAN, California J. DENNIS HASTERT, Illinois TOM LANTOS, California CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, Maryland ROBERT E. WISE, JR., West Virginia CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut MAJOR R. OWENS, New York STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York CHRISTOPHER COX, California PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida GARY A. CONDIT, California JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York STEPHEN HORN, California THOMAS M. BARRETT, Wisconsin JOHN L. MICA, Florida ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, Washington, THOMAS M. DAVIS, Virginia DC DAVID M. MCINTOSH, Indiana CHAKA FATTAH, Pennsylvania MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland JOE SCARBOROUGH, Florida DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio JOHN B. SHADEGG, Arizona ROD R. BLAGOJEVICH, Illinois STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois MARSHALL ‘‘MARK’’ SANFORD, South JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts Carolina JIM TURNER, Texas JOHN E. -

First Felines

SPRING 2021 NO. 40 First Felines Calvin Coolidge owned a variety of cats, including 4 housecats, a bobcat named Bob, and 2 lion cubs called Tax Reduction and Budget Bureau, according to the Coo- lidge Foundation. The housecats included Tiger, Blacky, Bounder, and Timmie. Blacky's favorite haunt was the White House elevator, whereas Timmie liked to hang out with the family canary perched between his shoul- ders. Tiger caused quite a stir when he went miss- ing. President Coolidge appealed to the people by calling for their help in a radio address. His beloved pet was lo- cated and returned to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The Kennedys kept several pets during their time at the presidential residence. Tom Kitten technically be- longed to Carolyn, JFK's daughter. Unfortunately, the cat had to be removed from office when it was discovered President Kennedy was allergic to felines. Tom Kitten was the first cat to receive an obituary notice from the press. Socks, Clinton’s famous cat Bill Clinton arrived at the White House with Presidential history has had it’s fair share of famous Socks, perhaps the most felines. They were not above reaching a paw across the famous presidential fe- aisle and uniting pet lovers from both parties. Here are line. The black and white just a few of the country's former "First Cats". cat was a media favorite Abraham Lincoln was the first president to bring cats and the subject of a chil- into the White House. Then Secretary of State William dren's book and a Seward (Alaska purchase fame) presented his boss with song. -

True Spies Episode 45 - the Profiler

True Spies Episode 45 - The Profiler NARRATOR Welcome ... to True Spies. Week by week, mission by mission, you’ll hear the true stories behind the world’s greatest espionage operations. You’ll meet the people who navigate this secret world. What do they know? What are their skills? And what would YOU do in their position? This is True Spies. NARRATOR CLEMENTE: With any equivocal death investigation, you have no idea where the investigation is going to take you, but in this particular investigation, it starts at the White House. That makes it incredibly difficult to conduct an investigation, when you know that two of the people that are intimately involved in it are the First Lady and the President of the United States. NARRATOR This is True Spies, Episode 45, The Profiler. This story begins with an ending. CLEMENTE: On the evening of January 20th, 1993, Vince Foster was found dead of by gunshot wound at the top of an earthen berm in Fort Marcy Park. NARRATOR A life cut short in a picturesque, wooded park 10 minutes outside of the US capital. He was found by someone walking through the park who then called the US park police. The park police and EMTs responded to the scene and the coroner then arrived and pronounced Foster dead. And his body was removed. NARRATOR A body, anonymous – housed in an expensive woolen suit, a crisp white dress shirt. A vivid bloodstain on the right shoulder. When they then searched his car that was in the parking lot they found a pass to the White House. -

Ten-Year Strategic Plan from the Desk of the Chair at CEEGS, We Are Always Looking Forward

The Ohio State University College of Engineering Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Geodetic Science Ten-Year Strategic Plan From the Desk of the Chair At CEEGS, we are always looking forward. September 2004 Into the future. Greetings Friends, Alumni and Supporters, Beyond our decade. Hoping to better understand the challenges our students, our faculty, and our constituents Welcome to The Ohio State University’s will face. Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering & Geodetic Science Ten-Year Strategic Plan. We're focused on knowing what society will need from our craft. I am pleased to present in these pages our Not just in the next year. department’s dynamic scenarios for addressing Or the next. uncertainties and questions facing our profession But well into this new century. and our ongoing strategic goals. It represents an enormous amount of hard work and thoughtful Beyond 2010. insight from various internal and external stake- holders, including faculty, staff, students, alumni, When specialization has been replaced by engineers, scientists, policy-makers, business pro- interdependencies. fessionals and consultants. When what may seem like the smallest considerations in Ohio will have significant I am confident that our plan will greatly aid our impact across the entire globe. department in reaching and exceeding many of When even the most natural systems of our the ambitious scenarios and long-range goals society have been fully integrated into the we’ve set forth herewith. human-designed technologies that connect our lives. On behalf of our department, I would like to express our gratitude to the Board of Governor's At OSU, we're looking ahead to the time of The Ohio State University Civil Engineering when we will need to be more than planners. -

Pdf at OAPEN Library

Monitored Monitored Business and Surveillance in a Time of Big Data Peter Bloom First published 2019 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Peter Bloom 2019 The right of Peter Bloom to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3863 7 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3862 0 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7868 0392 4 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0394 8 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0393 1 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America Contents Acknowledgements vi Preface: Completely Monitored vii 1. Monitored Subjects, Unaccountable Capitalism 1 2. The Growing Threat of Digital Control 27 3. Surveilling Ourselves 51 4. Smart Realities 86 5. Digital Salvation 112 6. Planning Your Life at the End of History 138 7. Totalitarianism 4.0 162 8. The Revolution Will Not Be Monitored 186 Notes 203 Index 245 Acknowledgements This is dedicated to everyone in the DPO – thank you for letting me be your temporary Big Brother and for the opportu- nity to change the world together. -

The Politics of Feasible Socialism

ENDORSEMENT n. the occarion of the first nmtingr of the gov at the time of the April 2000 meetings of the erning bodier of the International Monetary World Bank and the International Moneta11 Fund 0 Fund (IMF) and the World Bank in the 21 rt (IMF) 10 Washington, DC. DSA/YDS will par century, we callfor the immediate stupension of the poli ticipate in the Mobilizatton for Global Jusucc, a cies and practices that have ca1md widerpread pover!J week of educational events and nonviolent p:o and mfftring among the worlds peoples, and damage to tests in Washington, which aim to promote m ·c the global environment. IJ:7e hold these inrlit11tionr respon equitable and democratically operated glom rible, along with the IVorldTrade Organization (WfO), stitutions in this time of sharp incguahty. I..ar~ for an unjurt global economic rystem. transnational corporations have gotten together: We issue this call in the name of global jus It's time for the rest of us. DSA believes Uu" tice, in solidarity with the peoples of the Global this is the appropriate follow-up to the protes o: South struggling for survival and dignity in the that derailed the \VfO meetings in Seattle face of unjust economic policies. Only when the fall. coercive powers of international financial insti DSA 1s joined in this mobilizanon b m tutions are rescinded shall governments be ac other organizations, such as Jubilee 2 • r countable first and foremost to the will of their Years is Enough, Global Exchange., and Pu people for equitable economJc development. Citizens's Global Trade Watch. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 141 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JUNE 8, 1995 No. 93 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE Cubans who escaped their homeland for f A message from the Senate by Mr. liberty in the United States. Lundregan, one of its clerks, an- Through the accord, the Clinton ad- PRAYER nounced that the Senate had passed ministration once again has shown its foreign policy ineptitude, and specifi- The Chaplain, Rev. James David with an amendment in which the con- cally its lack of vision and effective- Ford, D.D., offered the following pray- currence of the House is requested, a ness toward the formulation of a clear er: concurrent resolution of the House of the following title: Cuba policy. Instead of supporting the May we remember each morning, O desires for freedom for the Cuban peo- loving God, to be grateful for all Your H. Con. Res. 67. Concurrent resolution set- ting forth the congressional budget for the ple, the President has preferred to ac- good gifts to us and to all people and United States Government for the fiscal cept the empty promises from the ruler remind us during all the hours of the years 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, and 2002. of a totalitarian state who promotes day to have hearts of thanksgiving. At The message also announced that the terrorism, and is about to finish con- our best moments we know that the Senate insists upon its amendment to struction of a potentially dangerous gifts of thanksgiving and gratitude are the resolution (H. -

Clinton Presidential Records in Response to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Requests Listed in Attachment A

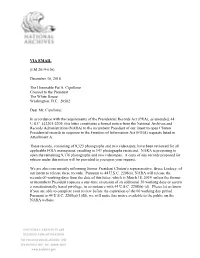

VIA EMAIL (LM 2019-016) December 18, 2018 The Honorable Pat A. Cipollone Counsel to the President The White House Washington, D.C. 20502 Dear Mr. Cipollone: In accordance with the requirements of the Presidential Records Act (PRA), as amended, 44 U.S.C. §§2201-2209, this letter constitutes a formal notice from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to the incumbent President of our intent to open Clinton Presidential records in response to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests listed in Attachment A. These records, consisting of 9,323 photographs and two videotapes, have been reviewed for all applicable FOIA exemptions, resulting in 147 photographs restricted. NARA is proposing to open the remaining 9,176 photographs and two videotapes. A copy of any records proposed for release under this notice will be provided to you upon your request. We are also concurrently informing former President Clinton’s representative, Bruce Lindsey, of our intent to release these records. Pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 2208(a), NARA will release the records 60 working days from the date of this letter, which is March 18, 2019, unless the former or incumbent President requests a one-time extension of an additional 30 working days or asserts a constitutionally based privilege, in accordance with 44 U.S.C. 2208(b)-(d). Please let us know if you are able to complete your review before the expiration of the 60 working day period. Pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 2208(a)(1)(B), we will make this notice available to the public on the NARA website. -

Holcomb Rides Trump/Pence Surge in Our September Survey, Gregg an Improbable Journey to Had a 40-35% Lead Over Holcomb

V22, N14 Thursday, Nov. 10, 2016 Holcomb rides Trump/Pence surge In our September survey, Gregg An improbable journey to had a 40-35% lead over Holcomb. In the win the governor’s office October survey Gregg was up just 41-39%. And in the November edition, it was tied By BRIAN A. HOWEY at 42%, with the Trump/Pence momentum INDIANAPOLIS – If you take the Octo- beginning to build. The presidential ticket ber WTHR/Howey Politics Indiana Poll and the went from 43-38% in October to a 48-37% Nov. 1-3 final survey and lead over Hillary Clinton in early November. draw a trend line, what you It was a precursor to a tidal wave, end up with in the Indiana an inverse tsunami, that was agitated by gubernatorial race is a the Oct. 28 letter from FBI Director James 51-45 upset victory by Eric Comey, tearing off Clinton’s email fiasco Holcomb over Democrat John Gregg. Continued on page 4 Pence’s Trump cigar By BRIAN A. HOWEY NASHVILLE, Ind. – “Do you want to see something really cool?” Sure. I was with Liz Murphy, an aide to Vice President Dan Quayle and we were in his ornate office at “Donald Trump is going to be the Old Executive Office Building next to the White House. our president. I hope that he will We walked into an office similar in size and scope to the be a successful president for all Indiana governor’s office at the Americans. We owe him an open Statehouse. We ended up be- fore an antique colonial revival- mind and a chance to lead.” style double-pedestal desk - Democratic presidential Theodore Roosevelt brought to the White House in 1903. -

Triangulating the Rhetorical with the Economic Metaphor

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2004-07-16 The Valuation of Literature: Triangulating the Rhetorical with the Economic Metaphor Melissa Brown Gustafson Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Gustafson, Melissa Brown, "The Valuation of Literature: Triangulating the Rhetorical with the Economic Metaphor" (2004). Theses and Dissertations. 180. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/180 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE VALUATION OF LITERATURE: TRIANGULATING THE RHETORICAL WITH THE ECONOMIC METAPHOR by Melissa B. Gustafson A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Master of English Department of English Brigham Young University August 2004 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Melissa B. Gustafson This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. ______________________________________________________________________________ Date Nancy L. Christiansen, Chair ______________________________________________________________________________