Art Studio 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Arts Curriculum Guide

Visual Arts Madison Public Schools Madison, Connecticut Dear Interested Reader: The following document is the Madison Public Schools’ Visual Arts Curriculum Guide If you plan to use the whole or any parts of this document, it would be appreciated if you credit the Madison Public Schools, Madison, Connecticut for the work. Thank you in advance. Table of Contents Foreword Program Overview Program Components and Framework · Program Components and Framework · Program Philosophy · Grouping Statement · Classroom Environment Statement · Arts Goals Learner Outcomes (K - 12) Scope and Sequence · Student Outcomes and Assessments - Grades K - 4 · Student Outcomes and Assessments - Grades 5 - 8 · Student Outcomes and Assessments / Course Descriptions - Grades 9 - 12 · Program Support / Celebration Statement Program Implementation: Guidelines and Strategies · Time Allotments · Implementation Assessment Guidelines and Procedures · Evaluation Resources Materials · Resources / Materials · National Standards · State Standards Foreword The art curriculum has been developed for the Madison school system and is based on the newly published national Standards for Arts Education, which are defined as Dance, Music, Theater, and Visual Arts. The national standards for the Visual Arts were developed by the National Art Education Association Art Standard Committee to reflect a national consensus of the views of organizations and individuals representing educators, parents, artists, professional associations in education and in the arts, public and private educational institutions, philanthropic organizations, and leaders from government, labor, and business. The Visual Arts Curriculum for the Madison School System will provide assistance and support to Madison visual arts teachers and administrators in the implementation of a comprehensive K - 12 visual arts program. The material described in this guide will assist visual arts teachers in designing visual arts lesson plans that will give each student the chance to meet the content and performance, or achievement, standards in visual arts. -

GREEN PAPER Page 1

AMERICANS FOR THE ARTS PUBLIC ART NETWORK COUNCIL: GREEN PAPER page 1 Why Public Art Matters Cities gain value through public art – cultural, social, and economic value. Public art is a distinguishing part of our public history and our evolving culture. It reflects and reveals our society, adds meaning to our cities and uniqueness to our communities. Public art humanizes the built environment and invigorates public spaces. It provides an intersection between past, present and future, between disciplines, and between ideas. Public art is freely accessible. Cultural Value and Community Identity American cities and towns aspire to be places where people want to live and want to visit. Having a particular community identity, especially in terms of what our towns look like, is becoming even more important in a world where everyplace tends to looks like everyplace else. Places with strong public art expressions break the trend of blandness and sameness, and give communities a stronger sense of place and identity. When we think about memorable places, we think about their icons – consider the St. Louis Arch, the totem poles of Vancouver, the heads at Easter Island. All of these were the work of creative people who captured the spirit and atmosphere of their cultural milieu. Absent public art, we would be absent our human identities. The Artist as Contributor to Cultural Value Public art brings artists and their creative vision into the civic decision making process. In addition the aesthetic benefits of having works of art in public places, artists can make valuable contributions when they are included in the mix of planners, engineers, designers, elected officials, and community stakeholders who are involved in planning public spaces and amenities. -

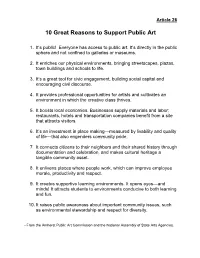

10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art

Article 26 10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art 1. It’s public! Everyone has access to public art. It’s directly in the public sphere and not confined to galleries or museums. 2. It enriches our physical environments, bringing streetscapes, plazas, town buildings and schools to life. 3. It’s a great tool for civic engagement, building social capital and encouraging civil discourse. 4. It provides professional opportunities for artists and cultivates an environment in which the creative class thrives. 5. It boosts local economies. Businesses supply materials and labor; restaurants, hotels and transportation companies benefit from a site that attracts visitors. 6. It’s an investment in place making—measured by livability and quality of life—that also engenders community pride. 7. It connects citizens to their neighbors and their shared history through documentation and celebration, and makes cultural heritage a tangible community asset. 8. It enlivens places where people work, which can improve employee morale, productivity and respect. 9. It creates supportive learning environments. It opens eyes—and minds! It attracts students to environments conducive to both learning and fun. 10. It raises public awareness about important community issues, such as environmental stewardship and respect for diversity. --From the Amherst Public Art Commission and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. The Amherst Public Art Commission Why Public Art for Amherst? Public art adds enormous value to the cultural, aesthetic and economic vitality of a community. It is now a well-accepted principle of urban design that public art contributes to a community’s identity, fosters community pride and a sense of belonging, and enhances the quality of life for its residents and visitors. -

Past Looking: Using Arts As Historical Evidence in Teaching History

Social Studies Research and Practice www.socstrp.org Past Looking: Using Arts as Historical Evidence in Teaching History Yonghee Suh Old Dominion University This is a comparative case study of how three high school history teachers in the U.S.A. use art in their practice. The following research question was investigated: How do secondary history teachers incorporate the arts—paintings, music, poems, novels, and films—in their teaching of history and why? Data were collected from three sources: interviews, observations, and classroom materials. Grounded theory was utilized to analyze the data. Findings suggest these teachers use the arts as historical evidence roughly for three purposes: First, to teach the spirit of an age; second, to teach the history of ordinary people invisible in official historical records; and third, to teach, both with and without art, the process of writing history. Two of the three teachers, however, failed to teach historical thinking skills through art. Keywords: history, history instruction, art, interdisciplinary approach, thinking skills, primary sources. Introduction Encouraging historical thinking in students is not a new idea in history education. Since the turn of the 20th century, many historians and history educators have argued that history consists of not only facts, but also historians’ interpretation of those facts, commonly known as the process of historical thinking, or how to analyze and interpret historical evidence, make historical arguments, and engage in historical debates (Bain, 2005; Holt, 1990; VanSledright; 2002; Wineburg, 2001). Many past reform efforts in history education have shared this commitment to teach students to think historically, in part by being engaged in the process of historical inquiry (Bradley Commission on History in Schools, 1988; National Center for History in the Schools, 1995). -

Line, Color, Space, Light, and Shape: What Do They Do? What Do They Evoke?

LINE, COLOR, SPACE, LIGHT, AND SHAPE: WHAT DO THEY DO? WHAT DO THEY EVOKE? Good composition is like a suspension bridge; each line adds strength and takes none away… Making lines run into each other is not composition. There must be motive for the connection. Get the art of controlling the observer—that is composition. —Robert Henri, American painter and teacher The elements and principals of art and design, and how they are used, contribute mightily to the ultimate composition of a work of art—and that can mean the difference between a masterpiece and a messterpiece. Just like a reader who studies vocabulary and sentence structure to become fluent and present within a compelling story, an art appreciator who examines line, color, space, light, and shape and their roles in a given work of art will be able to “stand with the artist” and think about how they made the artwork “work.” In this activity, students will practice looking for design elements in works of art, and learn to describe and discuss how these elements are used in artistic compositions. Grade Level Grades 4–12 Common Core Academic Standards • CCSS.ELA-Writing.CCRA.W.3 • CCSS.ELA-Speaking and Listening.CCRA.SL.1 • CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCSL.2 • CCSS.ELA-Speaking and Listening.CCRA.SL.4 National Visual Arts Standards Still Life with a Ham and a Roemer, c. 1631–34 Willem Claesz. Heda, Dutch • Artistic Process: Responding: Understanding Oil on panel and evaluating how the arts convey meaning 23 1/4 x 32 1/2 inches (59 x 82.5 cm) John G. -

Art for Art's Sake?

Art for Art’s Sake? OVERVIEW C entre for E ducational R esearch and I nnovation Art for Art’s Sake? OVERVIEW by Ellen Winner, Thalia R. Goldstein and Stéphan Vincent-Lancrin This overview is a slightly modified version of the conclusive chapter ofArt for Art’s Sake? The Impact of Arts Education. The complete version of the report can be consulted on line at http://dx.doi. org/10.1787/9789264180789-en. The work has benefited from support from Stiftung Mercator (Germany), from the French Ministry of Education and from the OECD Secretary General’s Central Priority Fund. They are thankfully acknowledged. This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Please cite this publication as: Winner, E., T. Goldstein and S. Vincent-Lancrin (2013), Art for Art’s Sake? Overview, OECD Publishing. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. Photo credits: Cover © Violette Vincent. Corrigenda to OECD publications may be found on line at: www.oecd.org/publishing/corrigenda. -

Art As Communication: Y the Impact of Art As a Catalyst for Social Change Cm

capa e contra capa.pdf 1 03/06/2019 10:57:34 POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE OF LISBON . PORTUGAL C M ART AS COMMUNICATION: Y THE IMPACT OF ART AS A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL CHANGE CM MY CY CMY K Fifteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society Against the Grain: Arts and the Crisis of Democracy NUI Galway Galway, Ireland 24–26 June 2020 Call for Papers We invite proposals for paper presentations, workshops/interactive sessions, posters/exhibits, colloquia, creative practice showcases, virtual posters, or virtual lightning talks. Returning Member Registration We are pleased to oer a Returning Member Registration Discount to delegates who have attended The Arts in Society Conference in the past. Returning research network members receive a discount o the full conference registration rate. ArtsInSociety.com/2020-Conference Conference Partner Fourteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society “Art as Communication: The Impact of Art as a Catalyst for Social Change” 19–21 June 2019 | Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon | Lisbon, Portugal www.artsinsociety.com www.facebook.com/ArtsInSociety @artsinsociety | #ICAIS19 Fourteenth International Conference on the Arts in Society www.artsinsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please visit the CGScholar Knowledge Base (https://cgscholar.com/cg_support/en). -

Fine Arts Standards Framework State Goals 25 - 27 2 State Goal 25

FINE ARTS STANDARDS FRAMEWORK STATE GOALS 25 - 27 2 STATE GOAL 25 STATE GOAL 25: Students will know the Language of the Arts Why Goal 25 is important: Through observation, discussion, interpretation, and analysis, students learn the “language” of the arts. They learn to understand how others express ideas in dance, drama, music, and visual art forms. In addition to acquiring knowledge essential to performance and production, students become arts consumers (e.g., attending live performances or movies, purchasing paintings or jewelry, or visiting museums) who understand the basic elements and principles underlying art works and are able to critique them. Goal 25 is closely correlated with the goals of the National Standards for Arts Education: Students should be able to develop and present basic analyses of works of art from structural, historical, and cultural perspectives, and from combinations of those perspectives. This includes the ability to understand and evaluate work in the various arts disciplines. Students should be able to relate various types of arts knowledge and skills within and across the arts disciplines. This includes mixing and matching competencies and understandings in art-making, history and culture, and analysis in any arts-related project. Goal 25A: Students will understand the sensory elements, organizational principles, and expressive qualities of the arts. Early elementary Late elementary Middle/junior high school Early high school Late high school 25.A.1a Dance: 25.A.2a Dance: 25.A.3a Dance: 25.A.4 25.A.5 Identify -

Americans Speak out About the Arts

Americans Speak Out About the Arts An In-Depth Look at Perceptions and Attitudes about the Arts in America The American public is more broadly engaged in the arts than previously understood, believes that the arts play a vital role in personal well‐being and healthier communities, and that the arts are core to a well‐rounded education. 2© 2016 Americans for the Arts Introduction Americans Speak Out about the Arts is national public opinion survey conducted by Ipsos Public Affairs (the third largest survey research firm in the world) on behalf of Americans for the Arts. The poll was conducted in December 2015. To ensure precision in the findings, a sample of 3,020 adults were interviewed online (by way of comparison, the typical national political poll has a sample size of just 1,000 adults). The arts are a fundamental component of a healthy society—one that provides myriad benefits to the individual, community, and the nation: • Aesthetic: The arts create beauty and preserve it as part of culture • Creativity: The arts encourage creativity, a critical skill in a dynamic world • Expression: Artistic work lets us communicate our interests and visions • Identity: Arts goods, services, and experiences help define our culture • Innovation: The arts are sources of new ideas, futures, concepts, and connections • Preservation: Arts and culture keep our collective memories intact • Prosperity: The arts create millions of jobs and enhance economic health • Skills: Arts aptitudes and techniques are needed in all sectors of society and work • Social Capital: We enjoy the arts together, across races, generations, and places Because of the significance of the arts to American life, there are many studies that document the social, educational and economic impacts of the arts on communities. -

Introduction to Visual & Performing Arts

INTRODUCTION VISUAL AND PERFORMING ARTS STANDARDS Catalina Foothills School District June 2017 Introduction to the Visual and Performing Arts Standards The Catalina Foothills School District (CFSD) has a long-standing commitment to providing students with a comprehensive arts education. The adoption of the Visual and Performing Arts standards and programs signify CFSD’s understanding that the Arts are an essential part of a total program of study, and also contribute to raising overall student achievement. Artistically literate graduates are well-equipped with the creativity, communication, critical thinking, problem solving, and collaborative skills necessary to live rich, meaningful lives. The CFSD Visual and Performing Arts standards build upon the philosophy and goals of the 2014 National Core Arts Standards (NCAS) and the National Association for Music Education (NAfME) standards. The Arizona Academic Standards in the Arts (2015) are also referenced and used in the collective work. The standards provide a structure within which educators can provide all students with key arts experiences. Through creative practices (imagine, investigate, construct, reflect), these experiences help students to understand what it means to be artistically literate, and how that literacy prepares them for a lifetime of artistic pleasure and appreciation. Artistic Literacy The CFSD Academic Standards in the Visual and Performing Arts embrace the idea of artistic literacy – the ability of students to create art, perform and present art, respond to or critique art, and connect art to their lives and the world around them. Developing artistic literacy in our students is the overarching goal of arts learning and programming in CFSD. The following definition of artistic literacy from the National Coalition for Core Arts Standards (2014) guides the work: ARTISTIC LITERACY Artistic literacy is the knowledge and understanding required to participate authentically in the arts. -

Mesquite Arts Council/Arts Center Organizational History

Mesquite Arts Council/Arts Center Organizational History HISTORY Founded in 1981, the Mesquite Arts Council initially was a part of the Mesquite Chamber of Commerce Cultural Committee. Official recognition by the State of Texas occurred in 1984 as a result of the development of by-laws, articles of incorporation and tax exempt status. With the successful organization of the community theatre in 1985, the Arts Council assisted the band, chorus, and orchestra with an equitable allocation of hotel/motel tax monies. Delivery of the Local Cultural Grants Program in 1993 by the Arts Council, to the arts nonprofit community further solidified a commitment to arts services and continues to date. Currently, and in addition to the previously listed arts administration elements, the Mesquite Arts Council provides administrative support and policy making toward the operation of the Mesquite Arts Center, monthly publication of marketing materials, the public art program and both visual and performance presenting schedule. PROGRAMMING The Arts Council has broadened its arts and cultural responsibilities from initially sponsoring the Mesquite Music Festival to providing for the community a variety of events. Writer’s in the Schools & at Mesquite Libraries, a theatre season with The Black Box MAC Actors, JazzBreaks in June, Chamber Music (both instrumental and vocal) and the Summer Children’s Theatre/Art Camp are offered to the community with much of the programming available free to the public. Presenting local visual artists and touring art exhibits insures that the galleries support a variety of work, including photography, works on canvas including oils & watercolor, handwork including weaving & quilts, and sculpture. -

Fine Arts and Art History

FINE ARTS AND ART HISTORY • Minor in art history and fine arts (http://bulletin.gwu.edu/ arts-sciences/fine-arts-art-history/combined-minor-art- The Department of Fine Arts and Art History offers instruction history-fine-arts/) in the visual and creative arts. Its programs strengthens a student's ability to develop visual literacy, as well as critical GRADUATE thinking and creative skills. Classroom study is supplemented by partnerships with the art museums and libraries of Master's programs Washington, DC. • Master of Arts in the field of art history (http:// bulletin.gwu.edu/arts-sciences/fine-arts-art-history/ma-art- Fine Arts, an interdisciplinary program, fosters a rigorous, history/) experimental approach to art as students cultivate creative • Master of Fine Arts in the field of fine arts (http:// pursuits in the studio and beyond. bulletin.gwu.edu/arts-sciences/fine-arts-art-history/mfa/) Art History is rooted in direct, interpretive engagement with the visual arts. The program combines visual and historical FACULTY analyses with philosophical hypotheses and theoretical, Professors: B. von Barghahn, D. Bjelajac, T. Ozdogan, P. political debates. The curriculum promotes connections to the Jacks, L.F. Robinson. studio arts and interdisciplinary exchanges with other fields of inquiry. It also emphasizes the narrative qualities and rhetorical Associate Professors: A.B. Dumbadze (Chair), D. Kessmann, persuasiveness of art historical writing in dialogue with art B.K. Obler, S. Rigg. objects, spaces, and performances. Assistant Professors: J. Brown, M. Natif, J.G.H. Sham. Visit the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design website (https://corcoran.gwu.edu/) for additional information.