(Gauteng Division: Pretoria) Case Number

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The High Court of South Africa Gauteng Local Division, Johannesburg Daily Criminal Court Roll for the 2Nd Term Thursday 06 May 2021

THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA GAUTENG LOCAL DIVISION, JOHANNESBURG DAILY CRIMINAL COURT ROLL FOR THE 2ND TERM THURSDAY 06 MAY 2021 JOHANNESBURG HIGH COURT 1 MABESELE, J COURT REF NUMBER ACCUSED CHARGES REASON ON STATE ADVOCATE DEFENCE STATUS EST 6A 10/2/11/1 THE ROLL COUNSEL DAYS 202/066 Mpanza, Sakhi Mpanza Murder x 2 Pre-Trial Adv Mashego New Case 1 SS 112/2020 Magubane, Sizwe Boksburg Sithole, Johan Khumbulani MNGQIBISA-THUSI, J COURT REF NUMBER ACCUSED CHARGES REASON ON STATE ADVOCATE DEFENCE STATUS EST 6B 10/2/11/1 THE ROLL COUNSEL DAYS 2017/114 Ncube, Buhlangene Housebreaking Trial Adv Kowlas Ph 18 SS 079/2018 Brighton Robbery with Roodepoort Phakathi, Mduduzi aggravating Khumalo, Vusumzi Blessing circumstances MAKAMU, AJ COURT REF NUMBER ACCUSED CHARGES DATE STATE ADVOCATE DEFENCE STATUS EST 2C 10/2/11/1 COUNSEL DAYS 2 MUDAU, J COURT REF NUMBER ACCUSED CHARGES REASON ON STATE ADVOCATE DEFENCE STATUS EST 6C 10/2/11/1 THE ROLL COUNSEL DAYS 2020/036 Jijane, Thokozane Fraud x 5 Argument Adv R Barnard Ph 3 SS 094/2020 Kidnapping x 4 Boksburg Rape x 17 Robbery with Aggravating circumstances x 10 Attempted Murder 2015/149 Mokoena, Bongani Murder Trial Adv Ngodwana Red Case 15 SS 152/2015 Zwane, Mashinini Robbery Sandton Mashiane, Steven Unlawful possession of Firearm Unlawful possession of Ammunition YACOOB, J COURT REF NUMBER ACCUSED CHARGES REASON ON STATE ADVOCATE DEFENCE STATUS EST 4A 10/2/11/1 THE ROLL COUNSEL DAYS 2019/101 Zitha, Kamal Murder Trial Adv Van Wyk Red Case 10 SS 095/2019 Attempted Murder x 3 Johannesburg Unlawful possession -

SUPERIOR COURTS ACT 10 of 2013 (Gazette No. 36743, Notice

(28 February 2014 – to date) SUPERIOR COURTS ACT 10 OF 2013 (Gazette No. 36743, Notice No. 615 dated 12 August 2013. Commencement date: 23 August 2013 [Proc. No. R36, Gazette No. 36774]- with the exception of sections 29, 37 and 45 and Items No. 11 of Schedule 1 and No. 1.1 of Schedule 2) OFFICE OF THE CHIEF JUSTICE Directive: 3/2014 RENAMING OF COURTS IN TERMS OF SECTION 6 OF THE SUPERIOR COURTS ACT NO 10 OF 2013 Government Notice 148 in Government Gazette 37390 dated 28 February 2014. Commencement date: 28 February 2014. By virtue of the powers vested in me in terms of section 8 of the Superior Courts Act, 2013 (Act no 10 of 2013) (the Act) I, Mogoeng Mogoeng, the Chief Justice of the Republic of South Africa, hereby issue the following directive: The Act created a single High Court, with various divisions constituted in terms of section 6 of the Act. In this regard all court processes in the High Court shall be headed in accordance with the Act; and all court processes shall be as headed as follows: (a) "IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA" EASTERN CAPE DIVISION, GRAHAMSTOWN (b) "IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA" EASTERN CAPE LOCAL DIVISION, BHISHO (c) "IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA" EASTERN CAPE LOCAL DIVISION, MTHATHA (d) "IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA" EASTERN CAPE LOCAL DIVISION, PORT ELIZABETH (e) "IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA" FREE STATE DIVISION, BLOEMFONTEIN (f) "IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA" GAUTENG DIVISION, PRETORIA Prepared by: Page 2 of 2 (g) "IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA" GAUTENG LOCAL DIVISION, -

OFFICE of the CHIEF JUSTICE the Office of the Chief Justice Is an Equal Opportunity Employer

ANNEXURE J OFFICE OF THE CHIEF JUSTICE The Office of the Chief Justice is an equal opportunity employer. In the filling of vacant posts, the objectives of section 195(1)(i) of the Constitution of South Africa, 1996, the Employment Equity imperatives as defined by the Employment Equity Act, 1998 (Act55) of 1998) and the relevant Human Resources policies of the Department will be taken into consideration and preference will be given to Women and Persons with Disabilities. APPLICATIONS : National Office (Midrand)/ Constitutional Court: Braamfontein: Quoting the relevant reference number, direct your application to: The Director: Human Resources, Office of the Chief Justice, Private Bag X10, Marshalltown, 2107 or hand deliver applications to the Office of the Chief Justice, Human Resource Management, 188, 14th Road, Noordwyk, Midrand, 1685. Eastern Cape/ Port Elizabeth/ Grahamstown/ Bisho/ Umthatha/ East London: Quoting the relevant reference number, direct your application to: The Provincial Head, Office of the Chief Justice, Postal Address: Private Bag x 13012, Cambridge 5206, East London. Applications can also be hand delivered to 59 Western Avenue, Sanlam Park Building, 2nd Floor, Vincent 5242, East London Free State/ Supreme Court of Appeal: Bloemfontein: Quoting the relevant reference number, direct your application to: The Provincial Head, Office of the Chief Justice, Private Bag X20612, Bloemfontein, 9300 or hand deliver applications to the Free State High Court, Corner President Brand and Fontein Street, Bloemfontein, 9301 Gauteng (Provincial Centre) /Land Claims Court (Randburg)/ Johannesburg High Court/ Pretoria High Court/ Labour and Labour Appeals Court: Johannesburg: Quoting the relevant reference number, direct your application to: The Provincial Head, Office of the Chief Justice, Private Bag X7, Johannesburg, 2000. -

Applicant: Brad Christopher Wanless Sc

1 APPLICANT: BRAD CHRISTOPHER WANLESS SC COURT FOR WHICH CANDIDATE APPLIES: GAUTENG DIVISION 1. The candidate’s appropriate qualifications: 1.1. BA – University of KwaZulu-Natal (1983); 1.2. LLB – University of KwaZulu-Natal (1985); and 1.3. Diploma in Maritime Law – University of KwaZulu-Natal (1986). 1.4. Between 23 November 1988 and 31 July 1990 the candidate served as a public prosecutor in the District and Regional Magistrates’ Courts of Durban, KwaZulu-Natal. The reviewers consider this experience to be relevant and valuable to an application for a judicial appointment. 1.5. The candidate was a member of the Society of Advocates of KwaZulu-Natal between 01 December 1990 and 30 June 2016, and has been a member of the Legal Practice Council from 21 June 2019 to date of his application. The reviewers consider this experience to be relevant and valuable to an application for a judicial appointment. 1.6. The candidate achieved senior counsel status in June 2011, after approximately 20 years of practice as an advocate. The reviewers consider this period to be reflective of a successful but not stellar practice. 2 1.7. The candidate resigned from the KwaZulu-Natal Bar on 01 July 20161 but has not been removed from the roll of advocates.2 From 01 July 2016 to date, it seems the candidate has remained in professional practice and had several Acting Judge appointments. 1.8. From 2012 to date, the candidate has spent more than two years acting as a Judge predominantly in the High Court of the Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal Divisions.3 The reviewers consider this period to be indicative of a significant commitment to judicial office. -

In the High Court of South Africa, Mpumalanga Division

SAFLII Note: Certain personal/private details of parties or witnesses have been redacted from this document in compliance with the law and SAFLII Policy IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA, MPUMALANGA DIVISION, MIDDELBURG (LOCAL SEAT) (1) REPORTABLE: NO (2) OF INTEREST TO OTHER JUDGES: NO (3) REVISED: YES HF Brauckmann 15 MARCH 2021 SIGNATURE DATE CASE NO: 807/2021 In the matter between: LESLEY SKHUMBUZO KHATI APPLICANT And THE STATE RESPONDENT ___________________________________________________________________________ 1 JUDGMENT ___________________________________________________________________________ BRAUCKMANN AJ INTRODUCTION [1] This is an application to be released on bail after the Supreme Court of Appeal granted the applicant leave to appeal against his conviction and sentence. Applicant was convicted by the High Court of conspiracy to commit robbery with aggravating circumstances, robbery with aggravating circumstances, kidnapping, attempted murder and malicious damage to property. [2] The applicant was sentenced is currently serving the sentence. The sentences passed were: COUNT 1 - 5 Years imprisonment COUNT 2 - 20 Years imprisonment COUNT 3 - 2 Years imprisonment COUNT 4- 2 Years imprisonment 2 COUNT 5 - 2 Years imprisonment COUNT 6- 2 Years imprisonment COUNT 11 - 2 Years imprisonment His mother secured funds to enable his current attorney, Mr Coert Jordaan, to petition the Supreme Court of Appeal, which petition was successful, and to launch this application for bail. JURISDICTION [3] The Respondent argues that that this court does not have jurisdiction to hear the application for the release of the applicant on bail, in light of the order made by the Supreme Court of Appeal (“SCA”). The order annexed to the affidavit in support of this application specifically states that leave to appeal was granted to the Full Court of the Gauteng Division of the High Court, Pretoria. -

The High Court of South Africa Gauteng Local Division, Johannesburg Daily Criminal Court Roll for the 1St Term Monday 08 March 2021

THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA GAUTENG LOCAL DIVISION, JOHANNESBURG DAILY CRIMINAL COURT ROLL FOR THE 1ST TERM MONDAY 08 MARCH 2021 JOHANNESBURG HIGH COURT 1 MOKGOATLHENG, J COURT REF NUMBER ACCUSED CHARGES REASON ON STATE ADVOCATE DEFENCE STATUS EST 4F 10/2/11/1 THE ROLL COUNSEL DAYS MABESELE, J COURT REF NUMBER ACCUSED CHARGES REASON ON STATE ADVOCATE DEFENCE STATUS EST 2E 10/2/11/1 THE ROLL COUNSEL DAYS 2017/007 Durrant, Petrus Bail pending Adv Britz Mr Van Heerden Ph 1 SS 127/2018 Willem, Johannes petition Tarlton 2010/145 Mkhize, Mthadeni Murder x 4 Trial Adv Mushwana Red Case 20 SS 048/2010 Attempted Murder x 5 Orlando Robbery with aggravating circumstances 2019/157 Cele, Muziwoxolo Murder Trial Adv Mushwana Red Case 10 SS 019/2020 Attempted Murder Meadowlands Unlawful possession of Firearm Unlawful possession of Ammunition MAKAMU, AJ COURT REF NUMBER ACCUSED CHARGES REASON ON STATE ADVOCATE DEFENCE STATUS EST 2C 10/2/11/1 THE ROLL COUNSEL DAYS 09:00 2016/043 Dube, Jeremiah Fraud Trial Adv Majola In person Ph 24 SS 063/2016 Dube, Rebecca Money Laundering Adv Sereme Adv Van Niekerk 2 Johannesburg Ndlovu, Maxwell Mavhidzi In person Dube, Christopher Adv Dingiswayo Ramonew, Moehi Adv Bakako Constance Adv Potwana Shoniwa, Edward Adv Bosiki Radebe, Zamaswazi Audrey Adv Bosiki Nkosi, Octavia Thabile Adv Tshishonga Khanyile, Mfanafuthi Adv Gising Daniel Adv Tshishonga STRYDOM, J COURT REF NUMBER ACCUSED CHARGES REASON ON STATE ADVOCATE DEFENCE STATUS EST 4D 10/2/11/1 THE ROLL COUNSEL DAYS 2017/206 Mdlalose, Mluleki Attempted Murder Trial -

Superior Court Act: Intention to Excise Certain Magisterial Districts From

GOVERNMENT NOTICE 4 No. 40753 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 31 MARCH 2017 GENERAL NOTICES • ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT Justice and Constitutional Development, Department of/ Justisie en Staatkundige Ontwikkeling, Departement van DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT No. 2017 NOTICE 270 OF 2017 270 Superior Court Act (10/2013): Intention to excise certain Magisterial districts from the area of jurisdiction of the Gauteng Division and their inclusion under the jurisdiction of the North West Division of the High Court as part of the Rationalisation of the areas of jurisdiction of the divisions of the High Court of South Africa 40753 SUPERIOR COURT ACT, 2013 (ACT NO. 10 OF 2013): INTENTION TO EXCISE CERTAIN MAGISTERIAL DISTRICTS FROM THE AREA OF JURISDICTIONOF THE GAUTENG DIVISION AND THEIR INCLUSION UNDER THEJURISDICTION OF THE NORTH WEST DIVISION OF THE HIGH COURT AS PART OFTHE RATIONALISATION OF THE AREAS OF JURISDICTION OF THE DIVISIONSOF THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA I, Azwihangwisi Faith Muthambi, Acting Minister of Justice and CorrectionalServices, intend to, in terms of section 6(3) (a) and (C) of the Superior Court Act, 2013(Act No. 10of2013)- excise the magisterial districts listed under Column "A" from thearea under the jurisdiction of the Gauteng Division of the High Court and their inclusion into the area of jurisdiction of the North West Division of the High Courtas reflected in attached Schedule. Comments may be addressed in writing on or before 5 May 2017 to: TheDirector - General, Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, PrivateBag X81, Pretoria. 0001 for the attention of Mr M Moagi; email: Makmoagi(a¡ustice.gov.za/ Fax 0866291640. -

Legal Notices Wetlike Kennisgewings

June Vol. 672 11 2021 No. 44683 Junie ( PART 1 OF 2 ) LEGAL NOTICES II WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER QPENBARE VERKOPE 2 No. 44683 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2021 CONTENTS / INHOUD LEGAL NOTICES / WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER OPENBARE VERKOPE Sales in execution • Geregtelike verkope ............................................................................................................ 13 Public auctions, sales and tenders Openbare veilings, verkope en tenders ............................................................................................................... 137 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2021 No. 44683 3 4 No. 44683 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2021 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2021 No. 44683 5 6 No. 44683 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2021 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2021 No. 44683 7 8 No. 44683 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2021 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2021 No. 44683 9 10 No. 44683 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2021 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2021 No. 44683 11 12 No. 44683 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2021 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2021 No. 44683 13 SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER OPENBARE VERKOPE ESGV SALES IN EXECUTION • GEREGTELIKE VERKOPE Case No: 2493/19 "AUCTION" IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA (Western Cape Division, CAPE TOWN) In the matter between: FIRSTRAND BANK LIMITED (REGISTRATION NUMBER: 1929/001225/06), PLAINTIFF AND DERICK ESIAS KOEN (IDENTITY NUMBER: 7703065032080), 1ST DEFENDANT, SONJA -

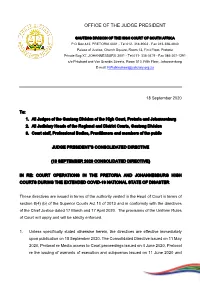

Gauteng Division Amended Consolidated Directives Effect From

OFFICE OF THE JUDGE PRESIDENT GAUTENG DIVISION OF THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA P O Box 442, PRETORIA 0001 - Tel 012- 314-9003 - Fax 012-326-4940 Palace of Justice, Church Square, Room 13, First Floor, Pretoria Private Bag X7, JOHANNESBURG 2001 - Tel 011- 335-0479 - Fax 086-207-1291 c/o Pritchard and Von Brandis Streets, Room 510, Fifth Floor, Johannesburg E-mail: [email protected] 18 September 2020 To: 1. All Judges of the Gauteng Division of the High Court, Pretoria and Johannesburg 2. All Judiciary Heads of the Regional and District Courts, Gauteng Division 3. Court staff, Professional Bodies, Practitioners and members of the public JUDGE PRESIDENT’S CONSOLIDATED DIRECTIVE (18 SEPTEMBER 2020 CONSOLIDATED DIRECTIVE) IN RE: COURT OPERATIONS IN THE PRETORIA AND JOHANNESBURG HIGH COURTS DURING THE EXTENDED COVID-19 NATIONAL STATE OF DISASTER These directives are issued in terms of the authority vested in the Head of Court in terms of section 8(4) (b) of the Superior Courts Act 10 of 2013 and in conformity with the directives of the Chief Justice dated 17 March and 17 April 2020. The provisions of the Uniform Rules of Court will apply and will be strictly enforced. 1. Unless specifically stated otherwise herein, the directives are effective immediately upon publication on 18 September 2020. The Consolidated Directive issued on 11 May 2020, Protocol re Media access to Court proceedings issued on 4 June 2020, Protocol re the issuing of warrants of execution and subpoenas issued on 11 June 2020 and Notice: Extension of the 11 May 2020 Consolidated Directive issued on 2 August 2020 are withdrawn and replaced with this Consolidated Directive. -

The South African Judiciary

THE SOUTH AFRICAN JUDICIARY 1 THE SOUTH AFRICAN JUDICIARY Constitutional Court Justices of South Africa 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE OF THE CHIEF JUSTICE ...................................................09 THE JUDICIARY IN SOUTH AFRICA ...................................................13 1. THE SOUTH AFRICAN JUDICIAL SYSTEM ..........................................23 2. JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS ...............................................................31 3. JUDICIAL TRAINING .........................................................................35 4. NATIONAL EFFICIENCY ENHANCEMENT COMMITTEE ........................39 4 5 THE SOUTH AFRICAN JUDICIARY THE SOUTH AFRICAN JUDICIARY THE JUDICIARY IN SOUTH AFRICA 6 7 THE SOUTH AFRICAN JUDICIARY MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF JUSTICE Message from Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng, Chief Justice of the Republic of South Africa and Vice-President of the CCJA 1. The Fourth Congress of the Conference of Constitutional Jurisdictions of Africa takes place in Cape Town from 23 to 26 April 2017. The South African Judiciary considers it a privilege and honour to host this Congress on South African soil. On behalf of the Judiciary of South Africa I welcome all our Colleagues in the Judiciary from throughout the length and breadth of our continent. A special word of welcome goes to all the speakers who accepted invitations to speak at this Congress. A number of them come from outside of our continent and we are grateful that they have taken their time to be with us. 2. It is appropriate that we tell you something about the South African Judiciary. We do that in the next few pages. The South African Judiciary enjoys a high degree of independence from the Legislative and Executive arms of government. Nevertheless, it has not reached the acceptable level of institutional independence. We continue to work hard towards the attainment of that objective. -

Legal Notices Wetlike Kennisgewings

Pr t ri 13 November 2020 Vol. 665 e 0 a, November No. 43899 C__ P_A_RT_1_0_F_2 __ ) LEGAL NOTICES WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER QPENBARE VERKOPE 2 No. 43899 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 13 NOVEMBER 2020 STAATSKOERANT, 13 NOVEMBER 2020 No. 43899 3 CONTENTS / INHOUD LEGAL NOTICES / WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER OPENBARE VERKOPE Sales in execution • Geregtelike verkope ....................................................................................................... 14 Gauteng ...................................................................................................................................... 14 Eastern Cape / Oos-Kaap ................................................................................................................ 105 Free State / Vrystaat ....................................................................................................................... 109 KwaZulu-Natal .............................................................................................................................. 116 Limpopo ...................................................................................................................................... 154 Mpumalanga ................................................................................................................................ 157 North West / Noordwes .................................................................................................................. -

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC of SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA July Vol. 649 Pretoria, 19 2019 Julie No. 42583 B LEGAL NOTICES WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS SALES IN EXECUTION AND OTHER PUBLIC SALES GEREGTELIKE EN ANDER OPENBARE VERKOPE ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 42583 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 42583 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 19 JULY 2019 IMPORTANT NOTICE OF OFFICE RELOCATION GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS PUBLICATIONS SECTION Dear valued customer, We would like to inform you that with effect from the 1st of August 2019, the Publications Section will be relocating to a new facility at the corner of Sophie de Bruyn and Visagie Street, Pretoria. The main telephone and facsimile numbers as well as the e-mail address for the Publications Section will remain unchanged. Our New Address: 88 Visagie Street Pretoria 0001 Should you encounter any difficulties in contacting us via our landlines during the relocation period, please contact: Ms Maureen Toka Assistant Director: Publications Cell: 082 859 4910 Tel: 012 748-6066 We look forward to continue serving you at our new address, see map below for our new location. Ctty of Tshwané ratmng J I , Municipal l ® MartmeM Of II T F- I I I t-Íi- e I r e i N ® 4- ® ®- LoretoConvent _-Y School, Pretoria power. L ® verai gTechrolo7 Government Printing Works 9l Publications _PAUITG Mintys Tyres Pretori est Star 88 Visagie Street II li - Visagie St Visagie St 9 Visagie St F p Visagie St Visa! Government Printing Works 0 altering National Museum of Cultural Malas Drive Style Centre jn Tshwane 9 The old Fire Station, PretoriaCentral Minnaar St mamar St } p Sepa Minnaar J 9Home This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za STAATSKOERANT, 19 JULIE 2019 No.