A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kronos Quartet Prelude to a Black Hole Beyond Zero: 1914-1918 Aleksandra Vrebalov, Composer Bill Morrison, Filmmaker

KRONOS QUARTET PRELUDE TO A BLACK HOLE BeyOND ZERO: 1914-1918 ALeksANDRA VREBALOV, COMPOSER BILL MORRISon, FILMMAKER Thu, Feb 12, 2015 • 7:30pm WWI Centenary ProJECT “KRONOs CONTINUEs With unDIMINISHED FEROCity to make unPRECEDENTED sTRING QUARtet hisTORY.” – Los Angeles Times 22 carolinaperformingarts.org // #CPA10 thu, feb 12 • 7:30pm KRONOS QUARTET David Harrington, violin Hank Dutt, viola John Sherba, violin Sunny Yang, cello PROGRAM Prelude to a Black Hole Eternal Memory to the Virtuous+ ....................................................................................Byzantine Chant arr. Aleksandra Vrebalov Three Pieces for String Quartet ...................................................................................... Igor Stravinsky Dance – Eccentric – Canticle (1882-1971) Last Kind Words+ .............................................................................................................Geeshie Wiley (ca. 1906-1939) arr. Jacob Garchik Evic Taksim+ ............................................................................................................. Tanburi Cemil Bey (1873-1916) arr. Stephen Prutsman Trois beaux oiseaux du Paradis+ ........................................................................................Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) arr. JJ Hollingsworth Smyrneiko Minore+ ............................................................................................................... Traditional arr. Jacob Garchik Six Bagatelles, Op. 9 ..................................................................................................... -

Festival of New Music

Feb rua ry 29 ESTIVA , F L O 20 F 12 , t N h e E L A W B M U S I C M A R C H Je 1 w i - sh 2 C -3 om , 2 mu 0 ni 12 ty Cen ter o f San Francisco 1 MUSICAL ADVENTURE CHARLESTON,TOUR SC MAY 31 - JUNE 4, 2012 PHILIP GLASS JOHN CAGE SPOLETO GUO WENJING Experience the Spoleto USA Festival with Other Minds in a musical adventure tour from May 31-June 4 in Charleston, SC. Attend in prime seating American premiere performances of two operas, Feng Yi Ting by Guo OTHER MINDS Wenjing and Kepler by Philip Glass, and a concert Orchestra Uncaged, featur- ing Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood and a US premiere of John Cage’s orches- tral trilogy, Twenty-Six, Twenty-Eight, and Twenty-Nine. The tour also includes: artist talks with Other Minds Artistic Director Charles Amirkhanian, Spoleto Festival USA conductor John Kennedy, & Festival Director Nigel Redden special appearance of Philip Glass discussing his work exclusive receptions at the festival day tours to Fort Sumter and an historic local plantation Tour partiticpants will stay in luxurious time to explore charming neighborhood homes & shopping boutiques accommodations at the Renaissance throughout Charleston Hotel in the heart of downtown Charleston, within walking distance to shops and JUNE 1 JUNE 3 restaurants. FENG YI TING ORCHESTRA UNCAGED American premiere John Kennedy, conductor CHARLESTON, SC Composed by Guo Wenjing Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra Directed by Atom Egoyan The Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra, led An empire at stake; two powerful men in by Resident Conductor John Kennedy, love with the same exquisite, inscrutable presents a special program of music of woman; and a plot that will change the our time. -

Hour by Hour, Celebrating an Eclectic Festival Bang on a Can Marathon at Winter Garden

Hour by Hour, Celebrating an Eclectic Festival Bang on a Can Marathon at Winter Garden June 18, 2012 By Steve Smith However quixotic the notion of mounting a 12-hour concert is, and however impractical it can be to attend one in its entirety, I feel guilty when I am unable to be at the annual Bang on a Can Marathon from start to finish. I feel obliged to meet a challenge on its own terms, as I did when Bang on a Can celebrated its 20th anniversary with a 27-hour event in 2007. That said, practicalities do sometimes get in the way. And happily, there are ample thrills to be had by the more casual attendee, a category that presumably included most of the audience that filled the Winter Garden at the World Financial Center in Lower Manhattan on Sunday. According to numbers provided by Arts Brookfield, which helped to present the marathon, along with the River to River Festival, an estimated 10,000 attended the free event. I most regretted missing Lois V Vierk’s elemental “Go Guitars,” played by Dither at noon, and Gérard Grisey’s “Noir de l’Étoile,” performed by the percussion ensemble Talujon as midnight approached. But the nearly six hours I took in, from around 4 to 10 p.m., aptly demonstrated the expansive, inclusive approach to modern-music programming characteristic of Bang on a Can’s directors, the composers Michael Gordon, David Lang and Julia Wolfe. That breadth seemed even more impressive, given that this year’s marathon, the final New York event of Bang on a Can’s 25th-anniversary season, felt less rangy than its immediate predecessors. -

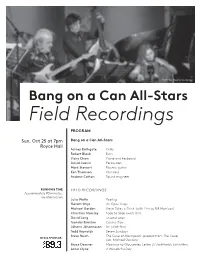

Field Recordings

Photo by Stephanie Berger Bang on a Can All-Stars Field Recordings PROGRAM Sun, Oct 25 at 7pm Bang on a Can All-Stars Royce Hall Ashley Bathgate Cello Robert Black Bass Vicky Chow Piano and keyboard David Cossin Percussion Mark Stewart Electric guitar Ken Thomson Clarinets Andrew Cotton Sound engineer RUNNING TIME FIELD RECORDINGS Approximately 90 minutes; no intermission Julia Wolfe Reeling Florent Ghys An Open Cage Michael Gordon Gene Takes a Drink (with film by Bill Morrison) Christian Marclay Fade to Slide (with film) David Lang unused swan Tyondai Braxton Casino Trem Jóhann Jóhannsson Hz (with film) Todd Reynolds Seven Sundays Steve Reich The Cave of Machpelah (excerpt from The Cave) MEDIA SPONSOR: (arr. Michael Gordon) Bryce Dessner Maximus to Gloucester, Letter 27 [withheld] (with film) Anna Clyne A Wonderful Day PROGRAM NOTES MESSAGE FROM THE CENTER: For 135 years recorded sound has permeated every corner of our For almost 25 years, the phrase Bang On A Can All-Stars lives, changing music along with everything else. Bartok and Kodaly has been synonymous with innovation in the world of took recording devices into the hills of central Europe and modern contemporary music. While the performer lineup may music was never the same; rock and roll’s lineage comes from change periodically, the symbiotic relationship between artists revealed to the world by the Lomaxes, the Seegers, and other musicians and modern composers remains staunchly and archivists. Hip-hop culture democratized sampling: popular music illuminatingly in place. today is a form of musique concrète, the voices & rhythms of the past mixing with the sound of machinery and electronics. -

The Films of Bill Morrison

FRAMING bernd herzogenrath (ed.) FILM (ED.) BERND HERZOGENRATH the films of bill morrison the films of bill morrison aesthetics of the archive Avant-garde filmmaker Bill Morrison has been making films that Bernd Herzogenrath THE FILMS OF BILL MORRISON combine archival footage and contemporary music for decades, teaches American literature and he has recently begun to receive substantial recognition: he was and culture at Goethe the subject of a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, and University of Frankfurt am his 2002 film Decasia was selected for the National Film Registry Main, Germany. by the Library of Congress. This is the first book-length study With contributions by of Morrison’s work, covering the whole of his career. It gathers Yasmin Afshar specialists throughout film studies to explore Morrison’s ‘aesthetics of Hanjo Berressem the archive’, his creative play with archival footage and his focus on Benjamin Betka the materiality of the medium of film. Johannes Binotto William Cusick David Gersten André Habib The definitive study of cinema’s foremost hauntologist! Bernd Herzogenrath Gorgeous, indispensable, moving! Eva Hoffmann Jan-Christopher Horak – GUY MADDIN, CANADIAN FILMMAKER Benjamin Léon Hans Morgenstern Andrea Pierron Simon Popple Bérénice Reynaud Sukhdev Sandhu Dan Streible Agnès Villete Lawrence Weschler FRAMING AUP.nl FILM 9789089649966 EYE FILMMUSEUM THE FILMS OF BILL MORRISON FRAMING FILM FRAMING FILM is a book series dedicated to theoretical and analytical studies in restoration, collection, archival, and exhibition practices in line with the existing archive of EYE Filmmuseum. With this series, Amsterdam University Press and EYE aim to support the academic research community, as well as practitioners in archive and restoration. -

The Orphanista Manifesto: Orphan Films and the Politics of Reproduction

Visual Anthropology REVIEW ESSAYS The Orphanista Manifesto: Orphan Films and the Politics of Reproduction EMILY COHEN New York University ABSTRACT In this essay, I review the works of filmmakers Bill Morrison and Gregorio Rocha and contextualize their work within agrowing apocalyptic cultural movement of film preservationists who identify as “orphanistas.” As orphanistas they struggle to reshape and reproduce cultural memory and heritage through reviving “orphans”—films abandoned by their makers. Moving images mimic cognitive memory, yet, depending on reproduc- tive technologies, copies of moving images may organize mass publics and influence cultural imaginaries. Traditionally consid- ered conservative, preservation in the midst of destruction is not FIGURE 1. The aftermath of the fire at the Cinemath´ eque` only a creative but also an avant-garde act of breathing new life Franc¸aise on August 3, 1980. Image from Nitrate Won’t Wait (1992) by Anthony Slide. into storytelling and the reproduction of cultural memory. In this essay, I discuss how the surrealist works of Morrison and Rocha radically confront dominant cultural imaginings of race and na- imminent demise, an old decaying silent film provokes an tion, and I argue that film preservation has the potential of being emotional landscape of urgency. socially transformative. An interview with Gregorio Rocha follows. Today, people who struggle to preserve and make avail- [Keywords: film archives, cultural memory, reproduction, race, able forgotten films that are decaying in archives, garages, nation] and basements call these dying films “orphans.” As an or- phanage, the film archive is transformed into a place of Prior to 1949, all motion pictures were made of nitro- forgotten, abandoned images and texts. -

Lisa Oman, Executive Director [email protected] | (415) 633-8802 View Press Kits

Contact: Lisa Oman, Executive Director [email protected] | (415) 633-8802 View Press Kits SF Contemporary Music Players present ‘Oceanic Migrations:’ a season-opening premiere event September 14, 2019 at The Cowell Theater, Fort Mason Cultural Center, featuring the world premiere of a new work by composer Michael Gordon, with special guest artists Splinter Reeds and Roomful of Teeth. ‘How Music is Made’ composer talk and panel with Michael Gordon, local and national archivists and historians precedes the concert on Saturday, September 14. SAN FRANCISCO (August 15, 2019) – San Francisco Contemporary Music Players (SFCMP) announces their season-opening event on Saturday, September 14, at the The Cowell Theater in Fort Mason Cultural Center, featuring the world premiere of a new, concert-length work by Bang On A Can co-founding composer Michael Gordon, and uniting for the first time ever the forces of the SF Contemporary Music Players with the preeminent Bay Area reed quintet Splinter Reeds and the GRAMMY Award-winning vocal ensemble Roomful of Teeth. Inspired by San Francisco’s history as a center for immigration, Gordon’s piece will look to Angel Island’s seat across the water in San Francisco Bay as one of many points of reference in the ongoing struggle between alienation and acceptance that underpins immigration to the United States. This concert is a part of SFCMP’s on STAGE series, which presents large-ensemble contemporary classical works of the most influential and innovative composers of our time. Michael Gordon, along with his Bang On A Can co-founders and compatriots, represents a distinct force in modern music. -

Dawson City: Frozen Time a Film by Bill Morrison

DAWSON CITY: FROZEN TIME A FILM BY BILL MORRISON “It is a story that is told, using these same films from the collection. It is both a cinema of mythology, and mythologizing of cinema. Gold and Silver, forever linked and following one another, drove the narrative in a unique chapter of human civilization.” - Bill Morrison U.S., 2016, 120 minutes, b&w and color Screens from DCP, 5.1 New York Publicity: Susan Norget Film Promotion Susan Norget / [email protected] Keaton Kail / [email protected] 212.431.0090 Distributor Contact: Rodrigo Brandão / VP of Marketing and Publicity Kino Lorber Inc. [email protected] 212.629.6880 Hypnotic Pictures & Picture Palace Pictures present In association with ARTE – La Lucarne In association with The Museum of Modern Art A film by Bill Morrison Directed/Written/Photographed and Edited by Bill Morrison Produced by Madeleine Molyneaux & Bill Morrison Music by Alex Somers Sound Design by John Somers Associate Producer: Paul Gordon Title Design: Galen Johnson World Premiere: Orizzonti Competition 73rd Mostra Internazionale D’Arte Cinematografica la Biennale di Venezia 2016 North American Premiere: Spotlight on Documentary New York Film Festival 2016 U.K. Premiere: Experimenta BFI/London Film Festival 2016 South American Premiere: Retrospective Valdivia International Film Festival 2016 2017 Intl Festival Screenings: International Film Festival Rotterdam (NL); Goteborg International Film Festival. (SE); !f Istanbul FF, Istanbul/Ankara, Turkey; FICUNAM. Mexico City (MX); Thessaloniki Doc Fest (GR); It’s All True, Sao Paolo, Brazil; BAFICI, Buenos Aires, Argentina 2 Synopsis Dawson City: Frozen Time, a feature length film by Bill Morrison (U.S.), pieces together the bizarre true history of a collection of 533 reels of film (representing 372 titles) dating from the 1910s to 1920s, which were lost for over 50 years until being discovered buried in a sub-arctic swimming pool deep in the Yukon Territory. -

BILL MORRISON in ONE LANDMARK BOX SET! “The Most Widely Acclaimed American Avant-Garde Film of the Fin De Siècle.” - J

“A TERRIFIC ACHIEVEMENT!” “ASTONISHING!” - LA TIMES (THE GREAT FLOOD) - SIGHT & SOUND (THE MINERS’ HYMNS) 16 FILMS BY BILL MORRISON IN ONE LANDMARK BOX SET! “THE MOST WIDELY accLAIMED American avant-GARDE FILM OF THE FIN DE SIÈCLE.” - J. HOBERMAN, THE Village VOICE (DECASIA) DISC 1 BLU-RAY (75 minutes) • DECASIA (67 minutes, 2002) • LIGHT IS CALLING (8 minutes, 2004) DISC 2 DVD (107 MINUTES) • CITY WALK (6 minutes, 1999) This landmark box set comprises 16 works by • PORCH (8 minutes, 2005) filmmaker and multimedia artist Bill Morrison, • HIGHWATER TRILOGY (31 minutes, 2006) called “one of the most adventurous American filmmakers” by Variety. Morrison’s work is char- • WHO BY WATER (18 minutes, 2007) acterized by his original approach to found, of- • JUST ANCIENT LOOPS (26 minutes, 2012) ten decaying film footage, and his close collab- oration with leading contemporary composers, • RE:AWAKENINGS (18 minutes, 2013) including Vijay Iyer, Jóhann Jóhannsson and Bill Frisell. Among other films this set includes his DISC 3 DVD (107 MINUTES) acclaimed masterpiece DECASIA (2002), a col- • THE MESMERIST (16 minutes, 2003) laboration with the composer Michael Gordon, • GHOST TRIP (23 minutes, 2000) selected to the US Library of Congress’ 2013 Na- tional Film Registry, now on Blu-ray, and nine • SPARK OF BEING (68 minutes, 2010) films never before available on DVD, including his most recent film RE:AWAKENINGS, with DISC 4 DVD (86 MINUTES) historic footage of Oliver Sacks and his “Awak- • THE MINERS’ HYMNS (52 minutes, 2011) enings” patients, and a score by Philip Glass. • RELEASE (13 minutes, 2010) BILL MORRISON: COLLECTED WORKS • OUTERBOROUGH (9 minutes, 2005) 1996 TO 2013 • THE FILM OF HER (12 minutes, 1996) 4 DVDs + 1 Blu-ray Booklet with articles and filmmaker’s interviews DISC 5 DVD UPC # 8-54565-00172-5 / SRP: $49.98 • THE GREAT FLOOD (80 minutes, 2013) Pre-book: August 19 • street DAte: sePteMber 23 http://HomeVideo.IcarusFilms.com • Tel: (800) 876-1610 • Email: [email protected]. -

Where Are You Taking Me

THE MINERS’ HYMNS A film by Bill Morrison Music by Jóhann Jóhannsson An Icarus Films Release Theatrical Opening: February 8, 2012 at Film Forum, New York Download images, press kit, video clips and more at http://icarusfilms.com/pressroom.html User: icarus Password: press ―A elegiac testament to the lost industrial culture of the Durham coalfields‖ –Sight & Sound ―The flickering figures of history as captured on film [are] creative fodder for Bill Morrison‖ –The Wall Street Journal Contact: (718) 488-8900 www.IcarusFilms.com Serious documentaries are good for you. SHORT SYNOPSIS The Miners’ Hymns is a inspired documentary depicting the ill-fated mining community in North East England. The film, which tells its story entirely without words, features a original score by the Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson and rare archival footage selected and edited by the American filmmaker Bill Morrison. LONG SYNOPSIS The Miners’ Hymns is a inspired documentary depicting the ill-fated mining community in North East England. The film, which tells its story entirely without words, features a original score by the Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson who collaborated on the project from its inception with the American filmmaker Bill Morrison. Using archival from the British Film Institute, the BBC, and other sources, The Miners Hymns celebrates social, cultural, and political aspects of the extinct industry, including the strong regional tradition of colliery brass bands. Focusing on the Durham coalfield located in the northeastern United Kingdom, the film depicts the hardship of pit work, the role of Trade Unions in organizing and fighting for workers' rights, the annual Miners' Gala in Durham. -

Anthracite Fields Music of the Coal Miner

LOS ANGELES MASTER CHORALE Grant Gershon, Kiki & David Gindler Artistic Director Anthracite Fields Music of the Coal Miner Sunday, March 6, 2016 — 7:30 pm Walt Disney Concert Hall Los Angeles Master Chorale Bang on a Can All-Stars Grant Gershon, conductor Keep Your Lamps arr. André Thomas This concert is made possible, in part, by the National Endowment David Cossin, percussion (b. 1952) for the Arts. All Is Well Sacred Harp Anthology (1844) Babel’s Streams Sacred Harp Anthology Journey Home Sacred Harp Anthology Wayfarin’ Stranger arr. Craig Zamer Kristen Toedtman, mezzo soprano | Scott Graff, baritone (b. 1978) KUSC is our Proud Media Partner The Promised Land Sacred Harp Anthology ListenUp! with composer Julia Wolfe, Artistic Director Grant Gershon and KUSC’s Alan Chapman We’ll Soon Be There Sacred Harp Anthology can be heard online after the concert at www.lamc.org. Wondrous Love Sacred Harp Anthology Your use of a ticket acknowledges your willingness to appear in photographs taken in public areas of Wade in the Water arr. Moses Hogan the Music Center and releases the Zanaida Robles, soprano (1957-2003) Center and its lessees and others from liability resulting from use of INTERMISSION such photographs. Use of any phones, cameras or recording devices is prohibited Anthracite Fields WEST COAST PREMIERE Julia Wolfe during the performance. Program I. Foundation (b. 1958) and artists subject to change. Latecomers will be seated at the II. Breaker Boys discretion of House Management. III. Speech Members of the audience who IV. Flowers leave during the performance will V. Appliances be escorted back into the concert hall at the sole discretion of House Bang on a Can All-Stars Management. -

Music by David Lang

ORIGINAL MOTION PICTURE SOUNDTRACK Music by David Lang THE VILLAGE DETECTIVE a song cycle a Bill Morrison film ORIGINAL MOTION PICTURE SOUNDTRACK Music by David Lang THE VILLAGE DETECTIVE a song cycle a Bill Morrison film FRODE ANDERSEN – accordion SHARA NOVA – voice words and music by David Lang David Lang’s music for The Village Detective © 2021 by Red Poppy (ASCAP) Administered worldwide by Universal Music Corp. (ASCAP) Recorded by Frode Andersen in Copenhagen, Denmark Mixed and mastered by Nick Lloyd in New Haven, CT 01 ask (1:20) 02 I cross the field (instrumental) (4:06) 03 rambling canister (1:34) 04 mz 1915 (1:35) 05 fall of the romanoffs (2:18) 06 darker village (1:29) 07 slow loop (2:49) 08 continuous fall (10:36) 09 simple tune (4:04) 10 simple tune slow (3:53) 11 epiphany (4:22) 12 the fragile eternal (3:13) 13 the fragile eternal low octave (3:12) 14 continuous present (4:55) 15 I cross the field (4:13) In July of 2016 I got an email from the Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhanns- film. He proposed writing a soundtrack for percussion instruments, which I son, telling me about how a commercial fisherman in Iceland had found four found somewhat curious, but I thought well, maybe he knew something that reels of a Soviet film in his net. I didn’t. The reels were recovered 20 miles off the west coast of Iceland: at the bottom, Tragically Jóhann died in February 2018 at the age of 48. I began to think and in the middle of, the Atlantic Ocean, not far from where the continental that the film I was making was about mortality.