Uinoa in the Kitchen Uinoa in the Kitchen Uinoa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

03-Mar-19 Primarie PD 2019

Primarie PD 2019 03-mar-19 COLLEGIO SEGGIO SPECIFICA SEDE INDIRIZZO COMUNI che votano nel seggio Collegio 11 21 SEGGI BANCHETTE, FIORANO CANAVESE, LESSOLO, SALERANO CANAVESE, 11 BANCHETTE SCUOLA MEDIA VIA TORRETTA SAMONE, Loranzé, Colleretto Giacosa, Parella, Quagliuzzo, Strambinello 11 CASTELLAMONTE SEDE PD LARGO TALENTINO 4 AGLIE', BALDISSERO CANAVESE, CASTELLAMONTE, TORRE CANAVESE ALA DI STURA, BALANGERO, BALME, CANTOIRA, CERES, SALA PIANO TERRA, PIAZZA DEL MUNICIPIO CHIALAMBERTO, COASSOLO TORINESE, GERMAGNANO, 11 CERES MUNICIPIO 12 GROSCAVALLO, LANZO TORINESE, LEMIE, MEZZENILE, MONASTERO DI LANZO, PESSINETTO, TRAVES, USSEGLIO, VIU' 11 CIRIE' SEDE PD CORSO MATTEOTTI 16 CIRIE', FIANO, ROBASSOMERO, SAN CARLO CANAVESE COLLERETTO BORGIALLO, CASTELNUOVO NIGRA, COLLERETTO CASTELNUOVO, 11 SALA COMUNALE PIAZZA MUNICIPIO CASTELNUOVO CHIESANUOVA, CINTANO ALBIANO D'IVREA, AZEGLIO, BOLLENGO, BORGOMASINO, BUROLO, CARAVINO, COSSANO CANAVESE, MAGLIONE, MERCENASCO, 11 COSSANO SALA MUNICIPALE VIA ROMA PALAZZO CANAVESE, PEROSA CANAVESE, PIVERONE, ROMANO CANAVESE, SAN MARTINO CANAVESE, SCARMAGNO, SETTIMO ROTTARO, STRAMBINO, VESTIGNE', VIALFRE' CANISCHIO, CUORGNE', PRASCORSANO, SAN COLOMBANO 11 CUORGNE' SEDE PD VIA GARIBALDI 27 BELMONTE, FRASSINETTO, INGRIA, PONT-CANAVESE, RONCO CANAVESE, VALPRATO SOANA 11 FORNO CANAVESE SALA COMUNALE VIA VITTORIO VENETO 1 FORNO CANAVESE, RIVARA 11 IVREA LOCALE VIA CASCINETTE 2 IVREA, CASCINETTE D'IVREA ALPETTE, CERESOLE REALE, LOCANA, NOASCA, RIBORDONE, 11 LOCANA SALA CONSILIARE MUNICIPIO SPARONE 11 MATHI SEDE PD VIA -

Progetto Territoriale Sistema Bibliotecario Di Ivrea E Canavese (To)

Progetto territoriale Sistema Bibliotecario di Ivrea e Canavese (To) Referente del progetto : Gabriella Ronchetti – Viviana D’Onofrio Biblioteca Civica di Ivrea 0125/410502 [email protected] Comune coordinatore : Ivrea (To) Sistema Bibliotecario di Ivrea e Canavese Centro rete Biblioteca Civica di Ivrea P.zza Ottinetti, 30 – 10015 IVREA Tel. 0125/410309 Fax 0125/45472 Indirizzo e-mail [email protected] Comuni coinvolti: 56 Comuni con le relative biblioteche civiche: Agliè, Albiano, Alice Castello, Banchette, Barbania, Bollengo, Borgaro Torinese, Borgofranco, Bosconero, Burolo, Caluso, Cascinette d'Ivrea, Caselle Torinese, Castellamonte, Cavaglià, Chiaverano, Ciconio, Ciriè, Colleretto Giacosa, Cossano, Cuorgnè, Favria, Forno Canavese, Ivrea, Lessolo, Locana, Mappano, Mathi, Mazzè, Montalto Dora, Nole, Oglianico, Orio Canavese, Ozegna, Pavone Canavese, Piverone, Pont Canavese, Pratiglione, Quincinetto, Rivara, Rivarolo Canavese, Rocca C.se, Rondissone, Rueglio, Samone, San Giorgio Canavese, Settimo Rottaro, Settimo Vittone, Sparone, Strambinello, Strambino, Tavagnasco Vauda Canavese, Vestignè, Vico Canavese, Villareggia Anno 2018 Un primo sguardo ai nostri volontari Numero di volontari coinvolti nel progetto NpL: 142 I volontari indicati si occupano ESCLUSIVAMENTE di NpL? Sì No X Se tra i volontari indicati SOLO ALCUNI si occupano 7 esclusivamente di NpL, indicare quanti sono sul totale: Se i volontari NON si occupano esclusivamente di NpL, descrivere come sono gestiti all’interno del progetto. I volontari che non si occupano esclusivamente di NpL si occupano dell’apertura delle biblioteche durante le letture ad alta voce organizzate a cura del Sistema bibliotecario; talvolta sono i volontari stessi a svolgere le mansioni di lettori per i bambini e le loro famiglie o per gli asili nido e le scuole dell’infanzia. -

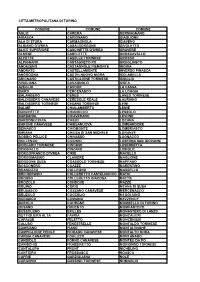

Città Metropolitana Di Torino Comune Comune Comune

CITTÀ METROPOLITANA DI TORINO COMUNE COMUNE COMUNE AGLIÈ CAREMA GERMAGNANO AIRASCA CARIGNANO GIAGLIONE ALA DI STURA CARMAGNOLA GIAVENO ALBIANO D'IVREA CASALBORGONE GIVOLETTO ALICE SUPERIORE CASCINETTE D'IVREA GRAVERE ALMESE CASELETTE GROSCAVALLO ALPETTE CASELLE TORINESE GROSSO ALPIGNANO CASTAGNETO PO GRUGLIASCO ANDEZENO CASTAGNOLE PIEMONTE INGRIA ANDRATE CASTELLAMONTE INVERSO PINASCA ANGROGNA CASTELNUOVO NIGRA ISOLABELLA ARIGNANO CASTIGLIONE TORINESE ISSIGLIO AVIGLIANA CAVAGNOLO IVREA AZEGLIO CAVOUR LA CASSA BAIRO CERCENASCO LA LOGGIA BALANGERO CERES LANZO TORINESE BALDISSERO CANAVESE CERESOLE REALE LAURIANO BALDISSERO TORINESE CESANA TORINESE LEINÌ BALME CHIALAMBERTO LEMIE BANCHETTE CHIANOCCO LESSOLO BARBANIA CHIAVERANO LEVONE BARDONECCHIA CHIERI LOCANA BARONE CANAVESE CHIESANUOVA LOMBARDORE BEINASCO CHIOMONTE LOMBRIASCO BIBIANA CHIUSA DI SAN MICHELE LORANZÈ BOBBIO PELLICE CHIVASSO LUGNACCO BOLLENGO CICONIO LUSERNA SAN GIOVANNI BORGARO TORINESE CINTANO LUSERNETTA BORGIALLO CINZANO LUSIGLIÈ BORGOFRANCO D'IVREA CIRIÈ MACELLO BORGOMASINO CLAVIERE MAGLIONE BORGONE SUSA COASSOLO TORINESE MAPPANO BOSCONERO COAZZE MARENTINO BRANDIZZO COLLEGNO MASSELLO BRICHERASIO COLLERETTO CASTELNUOVO MATHI BROSSO COLLERETTO GIACOSA MATTIE BROZOLO CONDOVE MAZZÈ BRUINO CORIO MEANA DI SUSA BRUSASCO COSSANO CANAVESE MERCENASCO BRUZOLO CUCEGLIO MEUGLIANO BURIASCO CUMIANA MEZZENILE BUROLO CUORGNÈ MOMBELLO DI TORINO BUSANO DRUENTO MOMPANTERO BUSSOLENO EXILLES MONASTERO DI LANZO BUTTIGLIERA ALTA FAVRIA MONCALIERI CAFASSE FELETTO MONCENISIO CALUSO FENESTRELLE MONTALDO -

The Impractical Supremacy of Local Identity on the Worthless Soils of Mappano Paolo Pileri1 and Riccardo Scalenghe2*

Pileri and Scalenghe City Territ Archit (2016) 3:5 DOI 10.1186/s40410-016-0035-z CASE STUDY Open Access The impractical supremacy of local identity on the worthless soils of Mappano Paolo Pileri1 and Riccardo Scalenghe2* Abstract Introduction: Soil is under pressure worldwide. In Italy, in the last two decades, land consumption has reached an average rate of 8 m2, demonstrating the failure of urban planning in controlling these phenomena. Despite the renewed recognition of the central role of soil resources, which has triggered numerous initiatives and actions, soil resources are still seen as a second-tier priority. No governance body exists to coordinate initiatives to ensure that soils are appropriately represented in decision-making processes. Global Soil Partnership draws our attention to the need for coordination to avoid fragmentation of efforts and wastage of resources. Both at a global and at a local level, the area of fertile soils is limited and is increasingly under pressure by competing land uses for settlement, infrastructure, raw materials extraction, agriculture, and forestry. Discussion and Evaluation: Here, we show that an administrative event, such as the creation of a new small municipality, can take place without any consideration of land and soil risks. This is particularly problematic in the Italian context as recent studies demonstrate that increasing local power in land use decisions coupled with weak control by the central administration and the high fragmentation and small dimension of municipalities has boosted land consumption. The fragmentation of municipalities has been detrimental to land conservation. Case description: The case study of Mappano (in the northwestern Italian region of Piedmont on the periphery of the regional capital city of Turin) is emblematic to demonstrate the role played by the supremacy of local identity or local interests despite the acknowledged importance of the key role played by soil everywhere. -

Uffici Locali Dell'agenzia Delle Entrate E Competenza

TORINO Le funzioni operative dell'Agenzia delle Entrate sono svolte dalle: Direzione Provinciale I di TORINO articolata in un Ufficio Controlli, un Ufficio Legale e negli uffici territoriali di MONCALIERI , PINEROLO , TORINO - Atti pubblici, successioni e rimborsi Iva , TORINO 1 , TORINO 3 Direzione Provinciale II di TORINO articolata in un Ufficio Controlli, un Ufficio Legale e negli uffici territoriali di CHIVASSO , CIRIE' , CUORGNE' , IVREA , RIVOLI , SUSA , TORINO - Atti pubblici, successioni e rimborsi Iva , TORINO 2 , TORINO 4 La visualizzazione della mappa dell'ufficio richiede il supporto del linguaggio Javascript. Direzione Provinciale I di TORINO Comune: TORINO Indirizzo: CORSO BOLZANO, 30 CAP: 10121 Telefono: 01119469111 Fax: 01119469272 E-mail: [email protected] PEC: [email protected] Codice Ufficio: T7D Competenza territoriale: Circoscrizioni di Torino: 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10. Comuni: Airasca, Andezeno, Angrogna, Arignano, Baldissero Torinese, Bibiana, Bobbio Pellice, Bricherasio, Buriasco, Cambiano, Campiglione Fenile, Cantalupa, Carignano, Carmagnola, Castagnole Piemonte, Cavour, Cercenasco, Chieri, Cumiana, Fenestrelle, Frossasco, Garzigliana, Inverso Pinasca, Isolabella, La Loggia, Lombriasco, Luserna San Giovanni, Lusernetta, Macello, Marentino, Massello, Mombello di Torino, Moncalieri, Montaldo Torinese, Moriondo Torinese, Nichelino, None, Osasco, Osasio, Pancalieri, Pavarolo, Pecetto Torinese, Perosa Argentina, Perrero, Pinasca, Pinerolo, Pino Torinese, Piobesi Torinese, Piscina, Poirino, Pomaretto, -

ALLEGATO 6 PIANO PROVINCIALE PROV TORINO A.S

ALLEGATO 6 PIANO PROVINCIALE PROV TORINO a.s. 2010/2011 Dati WEBI A.S. 2009/2010 ISCRITTI SETTEMBRE sono esclusi scuole presso ospedali e carceri Grado scolastico Denominazione Indirizzo e n. civico Frazione o Località Comune Provincia PROV DI TORINO Istituto Comprensivo DI AIRASCA VIA STAZIONE 37 AIRASCA TORINO Scuola dell'infanzia . VIA DEL PALAZZO 13 AIRASCA TORINO Scuola dell'infanzia DI SCALENGHE PIAZZA COMUNALE 7 SCALENGHE TORINO Scuola primaria DANTE ALIGHIERI VIA STAZIONE 26 AIRASCA TORINO Scuola primaria PRINCIPESSA DI PIEMONTE VIA TORINO 1 SCALENGHE TORINO Scuola primaria DI SCALENGHE VIA MAESTRA 20 VIOTTO SCALENGHE TORINO Scuola secondaria di I grado . VIA STAZIONE 37 AIRASCA TORINO Scuola secondaria di I grado DI SCALENGHE VIA S. MARIA 40 PIEVE SCALENGHE TORINO Istituto Comprensivo ALMESE PIAZZA DELLA FIERA 3/2 ALMESE TORINO Scuola dell'infanzia PETER PAN BORGATA CHIESA 8 RUBIANA TORINO Scuola dell'infanzia LA GIOSTRA VIA PELISSERE 16/A VILLAR DORA TORINO Scuola primaria REGIONE PIEMONTE PIAZZA COMBA 1 RIVERA ALMESE TORINO Scuola primaria FALCONE - BORSELLINO PIAZZA DELLA CHIESA 16 MILANERE ALMESE TORINO Scuola primaria MONSIGNOR SPIRITO ROCCI PIAZZA DELLA FIERA 3 ALMESE TORINO Scuola primaria G. SIMONE GIRODO PIAZZA ROMA 6 RUBIANA TORINO Scuola primaria COLLODI VIA PELISSERE 1 VILLAR DORA TORINO Scuola secondaria di I grado RIVA ROCCI PIAZZA DELLA FIERA 3/2 ALMESE TORINO Circolo Didattico . VIA CAVOUR 45 ALPIGNANO TORINO Scuola dell'infanzia SERGIO BORELLO VIA EX INTERNATI 7 ALPIGNANO TORINO Scuola dell'infanzia GOBETTI VIA BARACCA 16 ALPIGNANO TORINO Scuola dell'infanzia G. RODARI VIA PIANEZZA 49 ALPIGNANO TORINO Scuola primaria ANTONIO GRAMSCI VIA CAVOUR 45 ALPIGNANO TORINO Scuola primaria F. -

PIOSSASCO - RELAZIONE FINALE 2012-2013” Pagina 2

DIPARTIMENTO PROVINCIALE DI TORINO - Struttura semplice “ Attività di Produzione” Indagine “Campagna di rilevamento qualità dell’aria – PIOSSASCO - RELAZIONE FINALE 2012-2013” Pagina 2 L'organizzazione della campagna di monitoraggio e la validazione dei dati sono state curate dai tecnici del Gruppo di Lavoro “Monitoraggio della Qualità dell’Aria” del Dipartimento di Torino di Arpa Piemonte: dott.ssa Annalisa Bruno, sig. Giacomo Castrogiovanni, dott.ssa Marilena Maringo, sig. Fabio Pittarello, sig. Francesco Romeo, ing. Milena Sacco, sig. Vitale Sciortino, sig. Roberto Sergi, coordinati dal Dirigente con incarico professionale Dott. Francesco Lollobrigida. Si ringraziano l’assessore e il personale degli Uffici Tecnici del Comune di Piossasco per la collaborazione prestata. DIPARTIMENTO PROVINCIALE DI TORINO - Struttura semplice “ Attività di Produzione” Indagine “Campagna di rilevamento qualità dell’aria – PIOSSASCO - RELAZIONE FINALE 2012-2013” Pagina 3 INDICE CONSIDERAZIONI GENERALI SUL FENOMENO INQUINAMENTO ATMOSFERICO .......................................................................................................................5 L'aria e i suoi inquinanti.............................................................................................................6 IL LABORATORIO MOBILE .................................................................................................8 IL QUADRO NORMATIVO .....................................................................................................8 LA CAMPAGNA DI MONITORAGGIO.............................................................................11 -

D.T3.1.3. Fua-Level Self- Assessments on Background Conditions Related To

D.T3.1.3. FUA-LEVEL SELF- ASSESSMENTS ON BACKGROUND CONDITIONS RELATED TO CIRCULAR WATER USE Version 1 Turin FUA 02/2020 Sommario A.CLIMATE,ENVIRONMENT AND POPULATION ............................................... 3 A1) POPULATION ........................................................................................ 3 A2) CLIMATE ............................................................................................. 4 A3) SEALING SOIL ...................................................................................... 6 A4) GREEN SPACES IN URBANIZED AREAS ...................................................... 9 B. WATER RESOURCES ............................................................................ 11 B1) ANNUAL PRECIPITATION ...................................................................... 11 B2) RIVER, CHANNELS AND LAKES ............................................................... 13 B3) GROUND WATER .................................................................................. 15 C. INFRASTRUCTURES ............................................................................. 17 C1) WATER DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM - POPULATION WITH ACCESS TO FRESH WATER .................................................................................................... 17 C2) WATER DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM LOSS ..................................................... 18 C3) DUAL WATER DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM ..................................................... 18 C4) FIRST FLUSH RAINWATER COLLECTION ................................................ -

Convocazione Comizi Elettorali Per L’Elezione Del Consiglio Della Citta’ Metropolitana Di Torino

DECRETO DELLA SINDACA DELLA CITTA’ METROPOLITANA DI TORINO n. 283 - 17939/2016 OGGETTO: CONVOCAZIONE COMIZI ELETTORALI PER L’ELEZIONE DEL CONSIGLIO DELLA CITTA’ METROPOLITANA DI TORINO. LA SINDACA DELLA CITTA’ METROPOLITANA DI TORINO Dato atto che, a seguito della consultazione elettorale tenutasi nei giorni 5 giugno e 19 giugno 2016, la sottoscritta Chiara Appendino, nata a Moncalieri il 12.06.1984, è stata proclamata il 30 giugno 2016 Sindaca di Torino e conseguentemente, ai sensi dell’art. 1, comma 16, della Legge 7 aprile 2014 n. 56, Sindaca, altresì, della Città Metropolitana di Torino; Vista la legge 7 aprile 2014 n. 56 recante “Disposizioni sulle città metropolitane, sulle province, sulle unioni e fusioni dei comuni” e successive modificazioni e integrazioni; Vista la Legge 11 agosto 2014, n. 114, di conversione del Decreto Legge 24 giugno 2014 n. 90; Visto, in particolare, il comma 21 dell’articolo 1 della citata legge 56/2014, che prevede che, in caso di scioglimento del consiglio del comune capoluogo, si procede a nuove elezioni del consiglio metropolitano entro sessanta giorni dalla proclamazione del sindaco del comune capoluogo; Vista la nota della Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri – Conferenza Stato-Città ed Autonomie Locali, con la quale si dà atto che il termine di 60 giorni fissato dal succitato comma 21 della legge 56/2014 sia da interpretarsi come riferito non all’intero svolgimento delle elezioni, ma alla loro indizione. Visto, altresì, il comma 20 dell’art. 1 della citata legge 56/2014 che prevede che il Consiglio delle Città Metropolitane, con popolazione superiore a 800.000 abitanti e inferiore o pari a 3 milioni di abitanti, sia composto dal Sindaco Metropolitano, di diritto il Sindaco del Comune capoluogo, e da n. -

Elenco Dei Comuni Della Cintura E Numero Dei Buoni

ELENCO DEI COMUNI DELLA CINTURA E NUMERO DEI BUONI NECESSARI ELENCO DEI COMUNI DELLA CINTURA E NUMERO DEI BUONI NECESSARI La seguente tabella interessa i recapiti urgenti e i servizi TODAY, SPEED e SPEED + con partenza da Torino. Per le località non presenti nell’elenco la tariffa chilometrica è di €. 0,95 AL Km. (A/R) Balangero .......................... 12 Brandizzo .............................3 Caramagna Piemonte ....20 A Baldissero Canavese ....... 18 Bricherasio .......................20 Caravino ............................20 Acqui Terme .....................40 Baldissero d’Alba ............20 Brosso ................................ 24 Carema ..............................30 Agliè ....................................14 Baldissero Torinese .......... 6 Bruzolo ............................... 17 Carignano ............................5 Airasca ................................10 Balme ................................. 24 Bruino ...................................8 Carmagnola ....................... 12 Ala di Stura ....................... 24 Banchette ......................... 24 Brusasco ............................ 16 Casalborgone ...................14 Alba .................................... 26 Barbania ............................. 13 Buriasco .............................14 Casale Monferrato .......... 22 Albiano D’Ivrea ................ 24 Barbaresco .......................30 Burolo d’Ivrea .................. 24 Casalgrasso ....................... 13 Alessandria ....................... 48 Bardonecchia ................... 38 Busano -

Alto Canavese – Pianura Torinese Nord-Occidentale

Area forestale: Valli Ceronda e Casternone – Alto Canavese – Pianura Torinese Nord-Occidentale Piano Forestale Territoriale Rilievi, cartografie tematiche e relazioni tecniche Gruppo di lavoro: Silvio Durante (Coordinamento), Sergio Graziano, Marco Allocco, Maria Pianezzola, Guido Blanchard, Carlo Grosso Nicolin Metodologia, assistenza tecnica, controllo I.P.L.A. S.p.A. Istituto per le Piante da Legno e l’Ambiente Settore Vegetazione e Fauna Settore Cartografia ed Informatica Settore Suolo Coordinamento generale Regione Piemonte Direzione Economia montana e Foreste Settore Politiche forestali Torino – marzo 2002 INDICE DEL PIANO 0. INTRODUZIONE ...................................................................................................... 1 0.1. Presentazione – scopi.................................................................................................. 1 0.2. Incarico........................................................................................................................ 1 0.3. Aspetti normativi e rapporti con altri strumenti di pianificazione........................2 0.4. Sintesi della situazione colturale e delle prescrizioni contenute nel piano............2 0.5. Elaborati del piano - metodologia.............................................................................6 0.5.1. Indagini preliminari.....................................................................................................6 0.5.1.1. Ricerca catastale – Usi Civici...................................................................................... -

Dipartimenti Di Prevenzione Delle ASL Della Regione Piemonte Ambito Territoriale (Comuni)

Dipartimenti di prevenzione delle ASL della Regione Piemonte Ambito territoriale (comuni) 1 ASL Ambito territoriale ASL Città di Torino Torino Almese, Avigliana, Bardonecchia, Beinasco, Borgone Susa, Bruino, Bruzolo, Bussoleno, Buttigliera Alta, Caprie, Caselette, Cesana Torinese, Chianocco, Chiomonte, Chiusa di San Michele, Claviere, Coazze, Collegno, Condove, Exilles, Giaglione, Giaveno, Gravere, Grugliasco, Mattie, Meana di Susa, Mompantero, Moncenisio, Novalesa, Orbassano, Oulx, Piossasco, Reano, Rivalta di Torino, Rivoli, Rosta, Rubiana, Salbertrand, San Didero, San Giorio di Susa, Sangano, Sant’ambrogio di Torino, Sant’Antonino di Susa, Sauze di Cesana, Sauze d’Oulx, Susa, Trana, Vaie, Valgioie, Venaus, Villar Dora, Villar Focchiardo, Villarbasse, Volvera, Alpignano, Druento, ASL TO3 Givoletto, La Cassa, Pianezza, San Gillio, Val della Torre, Venaria Reale, Airasca, Angrogna, Bibiana, Bobbio Pellice, Bricherasio, Buriasco, Campiglione Fenile, Cantalupa, Cavour, Cercenasco, Cumiana, Fenestrelle, Frossasco, Garzigliana, Inverso Pinasca, Luserna San Giovanni, Lusernetta, Macello, Massello, Osasco, Perosa Argentina, Perrero, Pinasca, Pinerolo, Piscina, Pomaretto, Porte, Pragelato, Prali, Pramollo, Prarostino, Roletto, Rorà, Roure, Salza di Pinerolo, San Germano Chisone, San Pietro Val Lemina, San Secondo di Pinerolo, Scalenghe, Sestriere, Torre Pellice, Usseaux, Vigone, Villafranca Piemonte, Villar Pellice, Villar Perosa, Virle Piemonte. Ala di Stura, Balangero, Balme, Barbania, Borgaro Torinese, Cafasse, Cantoira, Caselle Torinese,