Introduction N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

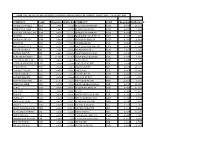

Code List 11 Invoice Currency

Code list 11 Invoice currency Alphabetical order Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region A BTN Bhutan ngultrum BOB Bolivian boliviano AFN Afghan new afghani BAM Bosnian mark ALL Albanian lek BWP Botswanan pula DZD Algerian dinar BRL Brazilian real USD American dollar BND Bruneian dollar AOA Angolan kwanza BGN Bulgarian lev ARS Argentinian peso BIF Burundi franc AMD Armenian dram AWG Aruban guilder AUD Australian dollar C AZN Azerbaijani new manat KHR Cambodian riel CAD Canadian dollar B CVE Cape Verdean KYD Caymanian dollar BSD Bahamian dollar XAF CFA franc of Central-African countries BHD Bahraini dinar XOF CFA franc of West-African countries BBD Barbadian dollar XPF CFP franc of Oceania BZD Belizian dollar CLP Chilean peso BYR Belorussian rouble CNY Chinese yuan renminbi BDT Bengali taka COP Colombian peso BMD Bermuda dollar KMF Comoran franc Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region CDF Congolian franc CRC Costa Rican colon FKP Falkland Islands pound HRK Croatian kuna FJD Fijian dollar CUC Cuban peso CZK Czech crown G D GMD Gambian dalasi GEL Georgian lari DKK Danish crown GHS Ghanaian cedi DJF Djiboutian franc GIP Gibraltar pound DOP Dominican peso GTQ Guatemalan quetzal GNF Guinean franc GYD Guyanese dollar E XCD East-Caribbean dollar H EGP Egyptian pound GBP English pound HTG Haitian gourde ERN Eritrean nafka HNL Honduran lempira ETB Ethiopian birr HKD Hong Kong dollar EUR Euro HUF Hungarian forint F I Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region ISK Icelandic crown LAK Laotian kip INR Indian rupiah -

The Other Migrants Preparing for Change

THE OTHER MIGRANTS PREPARING FOR CHANGE ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGES AND MIGRATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF MAURITIUS AN ASSESSMENT REPORT International Organization for Migration (IOM) 17 route des Morillons CH-1211 Geneva 19, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 717 9111 • Fax: +41 22 798 6150 E-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.iom.int The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 717 91 11 Fax: +41 22 798 61 50 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.iom.int _____________________________________________________ © 2011 International Organization for Migration (IOM) _____________________________________________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Zimra Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for the Period 13 to 19

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 13 TO 19 MAY 2021 USD BASE CURRENCY - USD DOLLAR CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 654.1789 0.0015 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 4.1305 0.2421 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 93.8650 0.0107 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 40.3500 0.0248 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 1.2830 0.7795 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 8.8351 0.1132 AUSTRIA EUR 0.8248 1.2125 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 58.5800 0.0171 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.3760 2.6596 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 14.0341 0.0713 BELGIUM EUR 0.8248 1.2125 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.8248 1.2125 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 10.7009 0.0935 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 1.3838 0.7227 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 5.2227 0.1915 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 380.4786 0.0026 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.7082 1.4121 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 900.0322 0.0011 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 1967.5281 0.0005 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 8.2889 0.1206 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 1.2117 0.8253 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.3845 2.6008 CHINESE RENMINBI YUAN CNY 6.4384 0.1553 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 152.0684 0.0066 CUBAN PESO CUP 24.1824 0.0414 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 3.7380 0.2675 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.8248 1.2125 PORTUGAL EUR 0.8248 1.2125 CZECH KORUNA CZK 20.9986 0.0476 QATARI RIYAL QAR 3.6400 0.2747 DANISH KRONER DKK 6.1333 0.1630 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 74.1987 0.0135 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 15.6800 0.0638 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 983.6942 0.0010 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 42.6642 0.0234 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 3.7500 0.2667 EURO EUR 0.8248 1.2125 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 1.3251 0.7547 FINLAND EUR 0.8248 1.2125 SPAIN EUR 0.8248 1.2125 FRANCE EUR 0.8248 1.2125 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 14.0341 0.0713 GERMANY -

ZIMRA Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for Period 24 Dec 2020 To

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 24 DEC 2020 - 13 JAN 2021 ZWL CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATEZIMRA RATECURRENCY CODE CROSS RATEZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 7.9981 0.1250 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 0.0497 20.1410 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 1.0092 0.9909 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 0.4819 2.0753 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 0.0162 61.7367 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 0.8994 1.1119 AUSTRIA EUR 0.0100 99.6612 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 0.9115 1.0972 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.0046 217.5176 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 0.1792 5.5819 BELGIUM EUR 0.0100 99.6612 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.0100 99.6612 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 0.1322 7.5356 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 0.0173 57.6680 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 0.0631 15.8604 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 4.7885 0.2088 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.0091 109.5983 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 11.0048 0.0909 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 23.8027 0.0420 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 0.1068 9.3633 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 0.0158 63.4921 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.0047 212.7090 CHINESE RENMINBI YUANCNY 0.0800 12.5000 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 1.9648 0.5090 CUBAN PESO CUP 0.3240 3.0863 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 0.0452 22.1111 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.0100 99.6612 PORTUGAL EUR 0.0100 99.6612 CZECH KORUNA CZK 0.2641 3.7860 QATARI RIYAL QAR 0.0445 22.4688 DANISH KRONER DKK 0.0746 13.4048 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 0.9287 1.0768 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 0.1916 5.2192 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 12.0004 0.0833 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 0.4792 2.0868 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 0.0459 21.8098 EURO EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 0.0163 61.2728 FINLAND EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SPAIN EUR 0.0100 99.6612 FRANCE EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 0.1792 5.5819 GERMANY EUR 0.0100 99.6612 -

Changes in Eating Habits and Food Traditions of Indo-Mauritians

Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge Vol. 15 (3), July 2016, pp. 355-362 Changes in eating habits and food traditions of Indo-Mauritians 1Trishnee Bhurosy & 2Rajesh Jeewon* 1Department of Applied Health Science, Indiana University School of Public Health, Bloomington, United States; 2Department of Health Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Mauritius, Réduit, Mauritius E-mail: [email protected] Received 08 May 2015, revised 04 February 2016 Over the past two decades, there has been a shift towards consumption of energy-dense, imported processed foods and fast foods accompanied by a neglect of the traditional diets in many developing countries. A neglect of traditional food (TF) systems is related to nutrition transition marked by an increased consumption of unhealthy processed foods and significant lifestyle changes such as inadequate time for meal preparation. This nutrition transition (NT) has also resulted in a rise in diet-related chronic conditions. The current review aims to discuss the importance of TF and diets of Indo-Mauritians who constitute the majority of the general population in Mauritius as well as outline drivers behind the present NT. Understanding the functional properties of traditional foods is important in developing interventions to reduce the rising prevalence of chronic conditions such as obesity in Mauritius. A priority in view of the prevailing chronic disease burden could be to revive the use of neglected TF with high nutritive benefits through local nutrition education programs targeting the general population and in addition, to improve awareness of the high nutritive values of local TF in the education system as well as encouraging food companies to market these foods in an edible manner. -

A.2. the Population of Mauritius: Facts and Trends

MMigrationigration in Mauritius A COUNTRY PROFILE 2013 M igration in Mauritius igration A COUNTRY PROFILE 2013 PROFILE A COUNTRY 17 route des Morillons, P.O. Box 17, 1211 Geneva 19, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 717 9111 • Fax: +41 22 798 6150 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: http://www.iom.int The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in the meeting of operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This publication was made possible through the financial support provided by the IOM Development Fund (IDF). Publisher: International Organization for Migration (IOM) 17 route des Morillons P.O. Box 17 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel: +41 22 717 91 11 Fax: +41 22 798 61 50 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int _____________________________________________________ © 2014 International Organization for Migration (IOM) _____________________________________________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Predictors of Hypertension in Mauritians with Normotension and Prehypertension at Baseline: a Cohort Study

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Kowlessur, S., Hu, Z., Heecharan, J., Wang, J., Dai, J. et al. (2018) Predictors of hypertension in Mauritians with normotension and prehypertension at baseline: a cohort study International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7): 1394 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071394 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-153834 International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Predictors of Hypertension in Mauritians with Normotension and Prehypertension at Baseline: A Cohort Study Sudhirsen Kowlessur 1,2, Zhibin Hu 1,*, Jaysing Heecharan 2, Jianming Wang 1, Juncheng Dai 1, Jaakko O. Tuomilehto 3, Stefan Söderberg 4 ID , Paul Zimmet 5 and Noël C. Barengo 6 1 Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 211166, China; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (J.W.); [email protected] (J.D.) 2 Ministry of Health and Quality of Life, Port Louis 11321, Mauritius; [email protected] 3 Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki, 00100 Helsinki, Finland; jaakko.tuomilehto@helsinki.fi 4 Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umeå University, SE-901 87 Umea, Sweden; [email protected] 5 Department of Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC 3800, Australia; [email protected] 6 Medical and Population Health Sciences Research, Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, USA; nbarengo@fiu.edu * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 April 2018; Accepted: 27 June 2018; Published: 2 July 2018 Abstract: Information on the predictors of future hypertension in Mauritians with prehypertension is scant. -

ASSESSING the CLIMATE CHANGE-MIGRATION NEXUS THROUGH the LENS of MIGRANTS: the Case of the Republic of Mauritius

This project is funded This project is implemented by the by the European Union International Organization for Migration ANOTHER MANAM? The forced migration of the population of Manam Island, Papua New Guinea, due to volcanic eruptions 2004–2005 eruptions volcanic due to Guinea, New of Manam Island, Papua of the population migration MANAM? The forced ANOTHER ASSESSING THE CLIMATE CHANGE-MIGRATION NEXUS THROUGH THE LENS OF MIGRANTS: 17 route des Morillons, P.O. Box 17 1211 Geneva 19, Switzerland The Case of the Republic of Mauritius Tel.: +41 22 717 9111 • Fax: +41 22 798 6150 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.iom.int This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union and of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Development Fund. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union or IOM. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. -

Zimra Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for the Period 18 to 24 March 2021 Usd Base Currency - Usd Dollar

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 18 TO 24 MARCH 2021 USD BASE CURRENCY - USD DOLLAR CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 619.8543 0.0016 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 4.1185 0.2428 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 91.1400 0.0110 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 40.2500 0.0248 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 1.2941 0.7728 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 9.0089 0.1110 AUSTRIA EUR 0.8404 1.1899 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 73.2000 0.0137 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.3760 2.6596 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 14.8977 0.0671 BELGIUM EUR 0.8404 1.1899 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.8404 1.1899 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 11.0132 0.0908 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 1.3939 0.7174 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 5.6248 0.1778 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 380.6510 0.0026 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.7204 1.3882 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 900.0122 0.0011 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 1952.9208 0.0005 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 8.4890 0.1178 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 1.2452 0.8031 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.3845 2.6008 CHINESE RENMINBI YUAN CNY 6.5027 0.1538 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 155.9525 0.0064 CUBAN PESO CUP 26.5000 0.0377 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 3.8600 0.2591 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.8404 1.1899 PORTUGAL EUR 0.8404 1.1899 CZECH KORUNA CZK 21.9538 0.0456 QATARI RIYAL QAR 3.6400 0.2747 DANISH KRONER DKK 6.2495 0.1600 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 73.0394 0.0137 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 15.7100 0.0637 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 989.0352 0.0010 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 40.6800 0.0246 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 3.7500 0.2667 EURO EUR 0.8404 1.1899 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 1.3464 0.7427 FINLAND EUR 0.8404 1.1899 SPAIN EUR 0.8404 1.1899 FRANCE EUR 0.8404 1.1899 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 14.8977 0.0671 GERMANY -

Payment Systems in Mauritius

THE PAYMENT SYSTEM IN MAURITIUS Table of Contents OVERVIEW OF THE NATIONAL PAYMENT SYSTEM IN MAURITIUS .......................... 79 1. INSTITUTIONAL ASPECTS .............................................................................................. 80 1.1 General legal aspects ................................................................................................... 80 1.2 Role of financial intermediaries that provide payment services ............................ 80 1.2.1 Domestic banks ................................................................................................ 81 1.2.2 Offshore banks ................................................................................................. 81 1.2.3 Non-bank financial institutions authorised to transact deposit-taking business .................................................................................... 81 1.2.4 Savings banks ................................................................................................... 82 1.2.5 Housing corporation ........................................................................................ 82 1.2.6 Development bank............................................................................................. 82 1.2.7 Foreign exchange dealers ................................................................................ 82 1.2.8 Other financial institutions ............................................................................... 83 1.3 Role of the central bank ............................................................................................ -

Mauritius April 2019

Poverty & Equity Brief Sub-Saharan Africa Mauritius April 2019 Between 2007 and 2012, Mauritius economic growth translated into moderate poverty reduction from 8.3 to 7.9 percent. The incidence of poverty measured at the lower middle-income class international poverty line ($3.20 a day (2011 PPP)) is low: it is estimated at 3.2 percent in 2012 and projected to decline to 2.9 percent in 2019. Better-off individuals benefited from economic growth more than poorer ones. Indeed, the shared prosperity premium was negative between 2006 and 2012 (-0.1 percent), with the poorest households posting a negative consumption growth. Inequality in household consumption was stable between 2006 and 2012 (with the Gini index at about 35.8), while income inequality, particularly from labor, has expanded rapidly, and it is now threatening the standards of living of the poor. The Gini index calculated on household labor income in per adult equivalent terms increased from 41.7 in 2001 to 50 in 2015. The main driver of surging household labor income inequality was the expansion of inequality in individual earnings, which can be attributed to the skills shortage associated with structural changes of the economy from traditional and low-skills sectors to services, notably professional, real estate, and financial services. This transformation generated a considerable increase in the demand for skilled workers. However, the supply failed to match the rising demand, notwithstanding the significant improvements in educational attainments of the Mauritian population. A well-targeted system of public transfers contributed to mitigate the rise in total income inequality. -

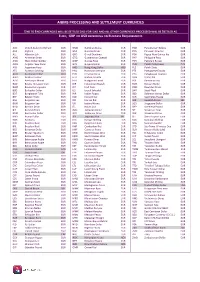

AIBMS Multicurrency List

AIBMS PROCESSING AND SETTLEMENT CURRENCIES END TO END CURRENCIES WILL BE SETTLED LIKE-FOR-LIKE AND ALL OTHER CURRENCIES PROCESSED WILL BE SETTLED AS EURO, GBP OR USD DEPENDING ON BUSINESS REQUIREMENTS AED United Arab Emi Dirham EUR GMD Gambian Dalasi EUR PAB Panamanian Balboa EUR AFA Afghani EUR GNF Guinean Franc EUR PEN Peruvian New Sol EUR ALL Albanian Lek EUR GRD Greek Drachma EUR PGK Papua New Guinea Kia EUR AMD Armenian Dram EUR GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal EUR PHP Philippine Peso EUR ANG West Indian Guilder EUR GWP Guinea Peso EUR PKR Pakistani Rupee EUR AON Angolan New Kwan EUR GYD Guyana Dollar EUR PLN Polish Zloty (new) PLN ARS Argentine Peso EUR HKD Hong Kong Dollar HKD PLZ Polish Zloty EUR ATS Austrian Schilling EUR HNL Honduran Lempira EUR PTE Portuguese Escudo EUR AUD Australian Dollar AUD HRK Croatian Kuna EUR PYG Paraguayan Guarani EUR AWG Aruban Guilder EUR HTG Haitian Gourde EUR QAR Qatar Rial EUR AZM Azerbaijan Manat EUR HUF Hungarian Forint EUR ROL Romanian Leu EUR BAD Bosnia-Herzogovinian EUR IDR Indonesian Rupiah EUR RUB Russian Ruble EUR BAM Bosnia Herzegovina EUR IEP Irish Punt EUR RWF Rwandan Franc EUR BBD Barbados Dollar EUR ILS Israeli Scheckel EUR SAR Saudi Riyal EUR BDT Bangladesh Taka EUR INR Indian Rupee EUR SBD Solomon Islands Dollar EUR BEF Belgian Franc EUR IQD Iraqui Dinar EUR SCR Seychelles Rupee EUR BGL Bulgarian Lev EUR IRR Iranian Rial EUR SEK Swedish Krona SEK BGN Bulgarian Lev EUR ISK Iceland Krona EUR SGD Singapore Dollar EUR BHD Bahrain Dinar EUR ITL Italian Lira EUR SHP St.Helena Pound EUR BIF Burundi