Perspective on Parrot Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Factors Influencing Density of the Northern Mealy Amazon in Three Forest Types of a Modified Rainforest Landscape in Mesoamerica

VOLUME 12, ISSUE 1, ARTICLE 5 De Labra-Hernández, M. Á., and K. Renton. 2017. Factors influencing density of the Northern Mealy Amazon in three forest types of a modified rainforest landscape in Mesoamerica. Avian Conservation and Ecology 12(1):5. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-00957-120105 Copyright © 2017 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Research Paper Factors influencing density of the Northern Mealy Amazon in three forest types of a modified rainforest landscape in Mesoamerica Miguel Ángel De Labra-Hernández 1 and Katherine Renton 2 1Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, México, 2Estación de Biología Chamela, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Jalisco, México ABSTRACT. The high rate of conversion of tropical moist forest to secondary forest makes it imperative to evaluate forest metric relationships of species dependent on primary, old-growth forest. The threatened Northern Mealy Amazon (Amazona guatemalae) is the largest mainland parrot, and occurs in tropical moist forests of Mesoamerica that are increasingly being converted to secondary forest. However, the consequences of forest conversion for this recently taxonomically separated parrot species are poorly understood. We measured forest metrics of primary evergreen, riparian, and secondary tropical moist forest in Los Chimalapas, Mexico. We also used point counts to estimate density of Northern Mealy Amazons in each forest type during the nonbreeding (Sept 2013) and breeding (March 2014) seasons. We then examined how parrot density was influenced by forest structure and composition, and how parrots used forest types within tropical moist forest. -

Abstract Book

Welcome to the Ornithological Congress of the Americas! Puerto Iguazú, Misiones, Argentina, from 8–11 August, 2017 Puerto Iguazú is located in the heart of the interior Atlantic Forest and is the portal to the Iguazú Falls, one of the world’s Seven Natural Wonders and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The area surrounding Puerto Iguazú, the province of Misiones and neighboring regions of Paraguay and Brazil offers many scenic attractions and natural areas such as Iguazú National Park, and provides unique opportunities for birdwatching. Over 500 species have been recorded, including many Atlantic Forest endemics like the Blue Manakin (Chiroxiphia caudata), the emblem of our congress. This is the first meeting collaboratively organized by the Association of Field Ornithologists, Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia and Aves Argentinas, and promises to be an outstanding professional experience for both students and researchers. The congress will feature workshops, symposia, over 400 scientific presentations, 7 internationally renowned plenary speakers, and a celebration of 100 years of Aves Argentinas! Enjoy the book of abstracts! ORGANIZING COMMITTEE CHAIR: Valentina Ferretti, Instituto de Ecología, Genética y Evolución de Buenos Aires (IEGEBA- CONICET) and Association of Field Ornithologists (AFO) Andrés Bosso, Administración de Parques Nacionales (Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable) Reed Bowman, Archbold Biological Station and Association of Field Ornithologists (AFO) Gustavo Sebastián Cabanne, División Ornitología, Museo Argentino -

Parrots in the Wild

Magazine of the World Parrot Trust May 2002 No.51 PsittaScene PsittaSceneParrots in the Wild Kakapo chicks in the nest (Strigops habroptilus) Photo by DON MERTON The most productive season since Kakapo have been intensively managed, 26 chicks had hatched by April. The female called Flossie Members’had two. Seen here are twoExpedition! young she hatched in February 1998. Our report on page 16 describes how she feeds her chicks 900 rimu fruits at each feed - at least four times every night! Supporting parrot conservation in the wild and promoting parrot welfare in captivity. Printed by Brewers of Helston Ltd. Tel: 01326 558000. ‘psittacine’ (pronounced ‘sit a sin’) meaning ‘belonging or allied to the parrots’ or ‘parrot-like’ 0 PsittaPsitta African Grey Parrot SceneScene Trade in Cameroon Lobeke National Park Editor By ANASTASIA NGENYI, Volunteer Biologist, Rosemary Low, WWF Jengi SE Forest Project, BP 6776, Yaounde, Cameroon Glanmor House, Hayle, Cornwall, The forest region of Lobeke in the Southeast corner of Cameroon has TR27 4HB, UK been the focus of attention over the past decade at national and international level, owing to its rich natural resource. Its outstanding conservation importance is due to its abundance of Anastasia Ngenyi. fauna and the rich variety of commercial tree species. Natural CONTENTS resources in the area face numerous threats due to the increased demand in resource exploitation by African Grey Parrot Trade ..................2-3 the local communities and commercial pressure owing to logging and poaching for the bush meat trade. Palm Sunday Success ............................4 The area harbours an unusually high density of could generate enormous revenue that most likely Conservation Beyond the Cage ..............5 forest mammals' particularly so-called "charismatic would surpass present income from illegal trade in Palm Cockatoo Conservation ..............6-7 megafauna" such as elephants, gorillas and parrots. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

A New Parrot Taxon from the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico—Its Position Within Genus Amazona Based on Morphology and Molecular Phylogeny

A new parrot taxon from the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico—its position within genus Amazona based on morphology and molecular phylogeny Tony Silva1, Antonio Guzmán2, Adam D. Urantówka3 and Paweª Mackiewicz4 1 Miami, FL, United States of America 2 Laboratorio de Ornitología, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Nuevo León, Mexico 3 Department of Genetics, Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences, Wroclaw, Poland 4 Faculty of Biotechnology, University of Wrocªaw, Wrocªaw, Poland ABSTRACT Parrots (Psittaciformes) are a diverse group of birds which need urgent protection. However, many taxa from this order have an unresolved status, which makes their conservation difficult. One species-rich parrot genus is Amazona, which is widely distributed in the New World. Here we describe a new Amazona form, which is endemic to the Yucatán Peninsula. This parrot is clearly separable from other Amazona species in eleven morphometric characters as well as call and behavior. The clear differences in these features imply that the parrot most likely represents a new species. In contrast to this, the phylogenetic tree based on mitochondrial markers shows that this parrot groups with strong support within A. albifrons from Central America, which would suggest that it is a subspecies of A. albifrons. However, taken together tree topology tests and morphometric analyses, we can conclude that the new parrot represents a recently evolving species, whose taxonomic status should be further confirmed. This lineage diverged from its closest relative about 120,000 years ago and was subjected to accelerated morphological and behavioral changes like some other representatives of the Submitted 14 December 2016 genus Amazona. -

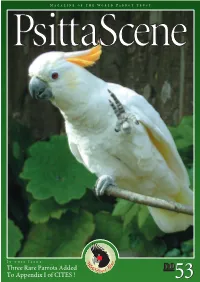

Three Rare Parrots Added to Appendix I of CITES !

PsittaScene In this Issue: Three Rare Parrots Added To Appendix I of CITES ! Truly stunning displays PPsittasitta By JAMIE GILARDI In mid-October I had the pleasure of visiting Bolivia with a group of avid parrot enthusiasts. My goal was to get some first-hand impressions of two very threatened parrots: the Red-fronted Macaw (Ara rubrogenys) and the Blue-throated Macaw (Ara SceneScene glaucogularis). We have published very little about the Red-fronted Macaw in PsittaScene,a species that is globally Endangered, and lives in the foothills of the Andes in central Bolivia. I had been told that these birds were beautiful in flight, but that Editor didn't prepare me for the truly stunning displays of colour we encountered nearly every time we saw these birds. We spent three days in their mountain home, watching them Rosemary Low, fly through the valleys, drink from the river, and eat from the trees and cornfields. Glanmor House, Hayle, Cornwall, Since we had several very gifted photographers on the trip, I thought it might make a TR27 4HB, UK stronger impression on our readers to present the trip in a collection of photos. CONTENTS Truly stunning displays................................2-3 Gold-capped Conure ....................................4-5 Great Green Macaw ....................................6-7 To fly or not to fly?......................................8-9 One man’s vision of the Trust..................10-11 Wild parrot trade: stop it! ........................12-15 Review - Australian Parrots ..........................15 PsittaNews ....................................................16 Review - Spix’s Macaw ................................17 Trade Ban Petition Latest..............................18 WPT aims and contacts ................................19 Parrots in the Wild ........................................20 Mark Stafford Below: A flock of sheep being driven Above: After tracking the Red-fronts through two afternoons, we across the Mizque River itself by a found that they were partial to one tree near a cornfield - it had sprightly gentleman. -

Retrospective Study of Ocular Disorders in Amazon Parrots1

Pesq. Vet. Bras. 29(12):979-984, dezembro 2009 Retrospective study of ocular disorders in Amazon parrots1 Ana Paula Hvenegaard2*, Angélica M.V. Safatle3, Marta B. Guimarães4, Antônio J.P. Ferreira5 and Paulo S.M. Barros6. ABSTRACT.- Hvenegaard A.P., Safatle A.M.V, Guimarães M.B. & Barros P.S.M. 2009. Retrospective study of ocular disorders in Amazon parrots. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira 29(12):979-984. Serviço de Oftalmologia do Hospital Veterinário, Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia, Universidade de São Paulo, Avenida Prof. Dr. Orlan- do Marques de Paiva 87, Cidade Universitária, São Paulo, SP 05508 270, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] A retrospective study was conducted to identify the occurrence and types of ocular disorders in 57 Amazon parrots admitted to the Ophthalmology Service, Veterinary Teaching Hospital, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of São Paulo, Brazil from 1997 to 2006. The most frequent observed disorder was cataracts, present in 24 of the 114 examined eyes (57 parrots). Uveitis, ulcerative keratitis and keratoconjunctivitis were frequently diagnosed as well. The cornea was the most affected ocular structure, with 28 reported disorders. Uveal disorders also were commonly observed. Conjunctiva and eyelid disorders were diagnosed in lower frequency. Results suggest that cataracts are common and that cornea, lens and uvea are the most affected ocular structures in Amazon parrots. INDEX TERMS: Amazon parrots, Amazona aestiva, Amazona amazonica, Amazona ochrocephala, cataracts, cornea, eye. RESUMO.- [Estudo retrospectivo das alterações ocu- cadas. A córnea foi a estrutura ocular mais acometida (28 lares observadas em papagaios.] Realizou-se estudo registros). Alterações uveais foram frequentemente ob- retrospectivo para identificar a ocorrência e os tipos de servadas. -

Conservation Concerns: T OP THREE NORTH a MERICAN PARROTS

Conservation Concerns: T OP THREE NORTH A MERICAN PARROTS Tom Marshall Green-cheeked Amazon (A. viridigenalis) Everyone knows that the gravest threat to most wildlife is failed due to avoidable problems in 1986 and ended in 1992. the relentless loss of habitat, and with respect to parrots, the Some of the reintroduced U.S. Tick-bills did breed in the wild added pressure of being subjected to poaching for the pet trade. and were visible into the late 1990s. A single Tick-billed parrot Te fragmentation or destruction of habitat and poaching was discovered at the southwestern ranch of Ted Turner in 2003, occurrences are frequently invisible to the eye. When it does and there may be some adults or ofspring out there yet. become apparent that an environment issue exists and action is required, it will most likely run afoul with certain life styles and Te greatest current threats to the Tick-billed parrot are from economic justifcations. Unfortunately, the crisis might often get continued logging of remaining mature and old growth pine-oak forest within the Sierra Madre Occidental and the vulnerability brief attention but, whatever action will be too little and often of young birds having to feed on their own in fragmented, too late. Te United States and Mexico share an interest in the scattered or unhealthy habitat with fewer and fewer mature conservation of the Tick-billed parrot, the Green conure, and the pines as well as some residual poaching. Practically the entire Green-cheeked or Mexican Red-headed Amazon, the subjects of habitat which constitutes the species’ breeding and wintering this article. -

Amazon Parrot

March 2013 SSqquuaawwkk TTaallkk Inside this Issue 1.Stolen Birds Bird of the Month: Amazons 2 Lost Bird Alert 3 Botanical Gardens 4 General Meeting Minutes 5 Board Meeting Minutes 6 Ads and Sponsors 7 The Coastal Bend Companion Bird Club and Rescue Mission seek to promote an interest in companion birds through communication with and education of pet owners, breeders and the general public. In addition, the CBCBC&RM strives to promote the welfare of all birds by CBCBC&RM providing monetary donations for the rescue and rehabilitation of wild birds and by placing abused, abandoned, lost or displaced companion birds in foster care until permanent adoptive homes can be found. Stolen Birds Dianna Wray • • Anyone who has information about the Originally published March 7, 2013 birds is asked to call 361-573-3836 or go at 8:21 p.m., updated March 8, 2013 to Earthworks, 102 E. Airline Road. Ask at 2 p.m. for Laurie Garretson. Mattie, the red-tailed African gray parrot, always greeted Laurie Garretson when she walked into Earthworks Nursery. Monday morning, there was no call of "hello" from Mattie. Her cage was empty, and the cage that held Gilbert, a green Mexican parrot, was gone. "They're a part of our family," Garretson said. "It just makes me sick that people can do things like this." The back door of the nursery was broken open, and two of Garretson's birds, Mattie REWARD and Gilbert, were gone. • A reward is being offered for any information leading to the return of Mattie, Garretson and her husband, Mark a red-tailed African gray parrot, and Garretson, started taking in birds more than Gilbert, a green Mexican parrot. -

Bio 209 Course Title: Chordates

BIO 209 CHORDATES NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA SCHOOL OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COURSE CODE: BIO 209 COURSE TITLE: CHORDATES 136 BIO 209 MODULE 4 MAIN COURSE CONTENTS PAGE MODULE 1 INTRODUCTION TO CHORDATES…. 1 Unit 1 General Characteristics of Chordates………… 1 Unit 2 Classification of Chordates…………………... 6 Unit 3 Hemichordata………………………………… 12 Unit 4 Urochordata………………………………….. 18 Unit 5 Cephalochordata……………………………... 26 MODULE 2 VERTEBRATE CHORDATES (I)……... 31 Unit 1 Vertebrata…………………………………….. 31 Unit 2 Gnathostomata……………………………….. 39 Unit 3 Amphibia…………………………………….. 45 Unit 4 Reptilia……………………………………….. 53 Unit 5 Aves (I)………………………………………. 66 Unit 6 Aves (II)……………………………………… 76 MODULE 3 VERTEBRATE CHORDATES (II)……. 90 Unit 1 Mammalia……………………………………. 90 Unit 2 Eutherians: Proboscidea, Sirenia, Carnivora… 100 Unit 3 Eutherians: Edentata, Artiodactyla, Cetacea… 108 Unit 4 Eutherians: Perissodactyla, Chiroptera, Insectivora…………………………………… 116 Unit 5 Eutherians: Rodentia, Lagomorpha, Primata… 124 MODULE 4 EVOLUTION, ADAPTIVE RADIATION AND ZOOGEOGRAPHY………………. 136 Unit 1 Evolution of Chordates……………………… 136 Unit 2 Adaptive Radiation of Chordates……………. 144 Unit 3 Zoogeography of the Nearctic and Neotropical Regions………………………………………. 149 Unit 4 Zoogeography of the Palaearctic and Afrotropical Regions………………………………………. 155 Unit 5 Zoogeography of the Oriental and Australasian Regions………………………………………. 160 137 BIO 209 CHORDATES COURSE GUIDE BIO 209 CHORDATES Course Team Prof. Ishaya H. Nock (Course Developer/Writer) - ABU, Zaria Prof. T. O. L. Aken’Ova (Course -

Of Parrots 3 Other Major Groups of Parrots 16

ONE What are the Parrots and Where Did They Come From? The Evolutionary History of the Parrots CONTENTS The Marvelous Diversity of Parrots 3 Other Major Groups of Parrots 16 Reconstructing Evolutionary History 5 Box 1. Ancient DNA Reveals the Evolutionary Relationships of the Fossils, Bones, and Genes 5 Carolina Parakeet 19 The Evolution of Parrots 8 How and When the Parrots Diversified 25 Parrots’ Ancestors and Closest Some Parrot Enigmas 29 Relatives 8 What Is a Budgerigar? 29 The Most Primitive Parrot 13 How Have Different Body Shapes Evolved in The Most Basal Clade of Parrots 15 the Parrots? 32 THE MARVELOUS DIVERSITY OF PARROTS The parrots are one of the most marvelously diverse groups of birds in the world. They daz- zle the beholder with every color in the rainbow (figure 3). They range in size from tiny pygmy parrots weighing just over 10 grams to giant macaws weighing over a kilogram. They consume a wide variety of foods, including fruit, seeds, nectar, insects, and in a few cases, flesh. They produce large repertoires of sounds, ranging from grating squawks to cheery whistles to, more rarely, long melodious songs. They inhabit a broad array of habitats, from lowland tropical rainforest to high-altitude tundra to desert scrubland to urban jungle. They range over every continent but Antarctica, and inhabit some of the most far-flung islands on the planet. They include some of the most endangered species on Earth and some of the most rapidly expanding and aggressive invaders of human-altered landscapes. Increasingly, research into the lives of wild parrots is revealing that they exhibit a corresponding variety of mating systems, communication signals, social organizations, mental capacities, and life spans.