Regulating Marriage in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communications Report of Special Procedures*

United Nations A/HRC/18/51 General Assembly Distr.: General 9 September 2011 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Eighteenth session Agenda item 5 Human rights bodies and mechanisms Communications Report of Special Procedures* Communications sent, 1 December 2010 to 31 May 2011; Replies received, 1 February 2011 to 31 July 2011 Joint report by the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to non-discrimination in this context; the Working Group on arbitrary detention; the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Cambodia; the Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography; the Independent Expert in the field of cultural rights; the Special Rapporteur on the right to education; the Working Group on enforced or involuntary disappearances; the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; the Special Rapporteur on the right to food; the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression; the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression; the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief; the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health; the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders; -

Pakistan: Death Plot Against Human Rights Lawyer, Asma Jahangir

UA: 164/12 Index: ASA 33/008/2012 Pakistan Date: 7 June 2012 URGENT ACTION DEATH PLOT AGAINST HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYER Leading human rights lawyer and activist Asma Jahangir fears for her life, having just learned of a plot by Pakistan’s security forces to kill her. Killings of human rights defenders have increased over the last year, many of which implicate Pakistan’s Inter- Service Intelligence agency (ISI). On 4 June, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) alerted Amnesty International to information it had received of a plot by Pakistan’s security forces to kill HRCP founder and human rights lawyer Asma Jahangir. As Pakistan’s leading human rights defender, Asma Jahangir has been threatened many times before. However news of the plot to kill her is altogether different. The information available does not appear to have been intentionally circulated as means of intimidation, but leaked from within Pakistan’s security apparatus. Because of this, Asma Jahangir believes the information is highly credible and has therefore not moved from her home. Please write immediately in English, Urdu, or your own language, calling on the Pakistan authorities to: Immediately provide effective security to Asma Jahangir. Promptly conduct a full investigation into alleged plot to kill her, including all individuals and institutions suspected of being involved, including the Inter-Services Intelligence agency. Bring to justice all suspected perpetrators of attacks on human rights defenders, in trials that meet international fair trial standards and -

Volume VIII, Issue-3, March 2018

Volume VIII, Issue-3, March 2018 March in History Nation celebrates Pakistan Day 2018 with military parade, gun salutes March 15, 1955: The biggest contingents of armoured and mech - post-independence irrigation anised infantry held a march-past. project, Kotri Barrage is Pakistan Army tanks, including the inaugurated. Al Khalid and Al Zarrar, presented March 23 , 1956: 1956 Constitution gun salutes to the president. Radar is promulgates on Pakistan Day. systems and other weapons Major General Iskander Mirza equipped with military tech - sworn in as first President of nology were also rolled out. Pakistan. The NASR missile, the Sha - heen missile, the Ghauri mis - March 23, 1956: Constituent sile system, and the Babur assembly adopts name of Islamic cruise missile were also fea - Republic of Pakistan and first constitution. The nation is celebrating Pakistan A large number of diplomats from tured in the parade. Day 2018 across the country with several countries attended the March 8, 1957: President Various aeroplanes traditional zeal and fervour. ceremony. The guest of honour at Iskandar Mirza lays the belonging to Army Avi - foundation-stone of the State Bank the ceremony was Sri Lankan Pres - Pakistan Day commemorates the ation and Pakistan Air of Pakistan building in Karachi. ident Maithripala Sirisena. passing of the Lahore Resolution Force demonstrated aer - obatic feats for the March 23, 1960: Foundation of on March 23, 1940, when the All- Contingents of Pakistan Minar-i-Pakistan is laid. India Muslim League demanded a Army, Pakistan Air Force, and audience. Combat separate nation for the Muslims of Pakistan Navy held a march-past and attack helicopters, March 14, 1972: New education the British Indian Empire. -

Child Custody in Classical Islamic Law and Laws of Contemporary Muslim World (An Analysis)

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 4 No. 5; March 2014 Child Custody in Classical Islamic Law and Laws of Contemporary Muslim World (An Analysis) Aayesha Rafiq Assistant Professor Fatima Jinnah Women University Pakistan; Formerly Research Scholar at University of California Los Angeles. Abstract This article attempts to deliberate on the child custody laws in classical Islamic texts and the contemporary Muslim World with special focus on development of child custody laws in Pakistan. For classical Islamic law, the article refers to the laws as stated in the compendiums of fiqh of sunni and shi’ i schools of thought as well as decisions of Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) his companions and leading Muslim jurists. For the purpose of this study, contemporary Muslim world is divided into Muslim majority regions of Central Asia and Caucasus, South Asia, Southeast Asia, North Africa, South Africa, West Africa, Horn of Africa and Middle East. A thorough analysis of customary practices, personal status laws and trends of courts in these Muslim majority regions is carried out. Effort is made to bring out similarities, differences and developments in child custody laws in contemporary Muslim world. The article is delimited to the discussion on child custody in cases of divorce, judicial separation or dissolution of marriage only. In the end it is suggested that uniform laws can be formulated for the entire Muslim world, in the light of Islamic principles and contemporary practices of the Muslim world. Keywords: child custody, Islamic law, fiqh, shariah, contemporary laws, divorce. 1. Introduction Cases of child custody fall under muamlat in compendiums of Islamic Fiqh. -

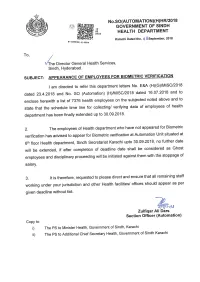

Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.No Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID

Details of Employees (Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID Women Medical 1 Dr. Afroze Khan Muhammad Chang (NULL) (NULL) Officer Women Medical 2 Dr. Shahnaz Abdullah Memon (NULL) 4130137928800 (NULL) Officer Muhammad Yaqoob Lund Women Medical 3 Dr. Saira Parveen (NULL) 4130379142244 (NULL) Baloch Officer Women Medical 4 Dr. Sharmeen Ashfaque Ashfaque Ahmed (NULL) 4140586538660 (NULL) Officer 5 Sameera Haider Ali Haider Jalbani Counselor (NULL) 4230152125668 214483656 Women Medical 6 Dr. Kanwal Gul Pirbho Mal Tarbani (NULL) 4320303150438 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 7 Dr. Saiqa Parveen Nizamuddin Khoso (NULL) 432068166602- (NULL) Officer Tertiary Care Manager 8 Faiz Ali Mangi Muhammad Achar (NULL) 4330213367251 214483652 /Medical Officer Women Medical 9 Dr. Kaneez Kalsoom Ghulam Hussain Dobal (NULL) 4410190742003 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 10 Dr. Sheeza Khan Muhammad Shahid Khan Pathan (NULL) 4420445717090 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 11 Dr. Rukhsana Khatoon Muhammad Alam Metlo (NULL) 4520492840334 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 12 Dr. Andleeb Liaqat Ali Arain (NULL) 454023016900 (NULL) Officer Badin S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID 1 MUHAMMAD SHAFI ABDULLAH WATER MAN unknown 1350353237435 10334485 2 IQBAL AHMED MEMON ALI MUHMMED MEMON Senior Medical Officer unknown 4110101265785 10337156 3 MENZOOR AHMED ABDUL REHAMN MEMON Medical Officer unknown 4110101388725 10337138 4 ALLAH BUX ABDUL KARIM Dispensor unknown -

The Constitution and Female-Initiated Divorce in Pakistan: Western Liberalism in Islamic Garb

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLG\34-2\HLG207.txt unknown Seq: 1 13-JUN-11 8:12 THE CONSTITUTION AND FEMALE-INITIATED DIVORCE IN PAKISTAN: WESTERN LIBERALISM IN ISLAMIC GARB KARIN CARMIT YEFET* “[N]o nation can ever be worthy of its existence that cannot take its women along with the men.” Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Founder of Pakistan1 The legal status of Muslim women, especially in family relations, has been the subject of considerable international academic and media interest. This Article examines the legal regulation of di- vorce in Pakistan, with particular attention to the impact of the nation’s dual constitutional commitments to gender equality and Islamic law. It identifies the right to marital freedom as a constitu- tional right in Pakistan and demonstrates that in a country in which women’s rights are notoriously and brutally violated, female di- vorce rights stand as a ray of light amidst the “darkness” of the general legal status of Pakistani women. Contrary to the conven- tional wisdom construing Islamic law as opposed to women’s rights, the constitutionalization of Islam in Pakistan has proven to be a potent tool in the service of women’s interests. Ultimately, I hope that this Article may serve as a model for the utilization of both Islamic and constitutional law to benefit women throughout the Muslim world. Introduction .................................................... 554 R I. All-or-Nothing: Classical Islam’s Gendered Divorce Regime ................................................. 557 R A. The Husband’s Right to Untie the Knot ............... 558 R * I wish to express my deep gratitude to Professors Akhil Reed Amar and Reva Siegel for their thoughtful and inspiring comments. -

AJCONF2019.Pdf

1 ASMA JAHANGIR CONFERENCE – 2019 ROADMAP FOR HUMAN RIGHTS 19 & 20TH OCTOBER, 2019 LAHORE 2 Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Conference Committee ................................................................................................................................ 9 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... 10 Aims & Objectives ...................................................................................................................................... 12 Synopsis ...................................................................................................................................................... 14 Day 1 ....................................................................................................................................................... 14 Day 2 ....................................................................................................................................................... 16 Resolutions: ................................................................................................................................................ 19 Theme A: Strengthening the Justice System ......................................................................................... 19 Topic 1 – Upholding the Rule of Law ................................................................................................ -

Asma Jahangir (1952‐2018): a Tragic Loss for South Asia and the World

Asma Jahangir (1952‐2018): A tragic loss for South Asia and the world (Bangkok/Kathmandu, 12 February, 2018) ‐ The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM‐ASIA) is deeply saddened by the sudden demise of eminent human rights defender, lawyer and social activist Asma Jahangir in Lahore, after she suffered a cardiac arrest on 11 February 2018. Asma Jahangir was known for her social activities in Pakistan and South Asia on gender, minority and human rights. Asma Jahangir was well‐known for her activism in the field of democracy, peace and justice globally, and has made an immense contribution in the South Asian region. She was associated with several human rights organisations, initiatives and networks for decades, both nationally and internationally. Born in Lahore on 27 January 1952, Asma was Pakistan’s first woman to serve as the President of the Supreme Court Bar Association of Pakistan from 2010 to 2012. She co‐founded and served as chairperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), a member of FORUM‐ASIA, from 1987 to 2011. She also contributed enormously to international legal standard setting while serving as the United Nations Special Rapporteur summary executionsand later as the United Nations Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion. After, she continued to be involved in several other capacities with the UN. She also co‐founded South Asians for Human Rights. Asma was a powerful voice against dictatorships and use of religion for political gains. She was also a staunch critic of the judiciary for not being pro‐active towards the oppressed. ‘Asma Jahangir was a person with extraordinary determination. -

LAHORE-Ren98c.Pdf

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S NAME PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 21233 MUHAMMAD M.YOUSAF H#56, ST#2, SIDIQUE COLONY RAVIROAD, 3/1/1960 MATRIC 10/07/2014 RAMZAN LAHORE, PUNJAB 2 26781 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD H/NO. 30, ST.NO. 6 MADNI ROAD MUSTAFA 10-1-1983 MATRIC 11/07/2014 ASHFAQ HAMZA IQBAL ABAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 3 29583 MUHAMMAD SHEIKH KHALID AL-SHEIKH GENERAL STORE GUNJ BUKHSH 26-7-1974 MATRIC 12/07/2014 NADEEM SHEIKH AHMAD PARK NEAR FUJI GAREYA STOP , LAHORE, PUNJAB 4 25380 ZULFIQAR ALI MUHAMMAD H/NO. 5-B ST, NO. 2 MADINA STREET MOH, 10-2-1957 FA 13/07/2014 HUSSAIN MUSLIM GUNJ KACHOO PURA CHAH MIRAN , LAHORE, PUNJAB 5 21277 GHULAM SARWAR MUHAMMAD YASIN H/NO.27,GALI NO.4,SINGH PURA 18/10/1954 F.A 13/07/2014 BAGHBANPURA., LAHORE, PUNJAB 6 36054 AISHA ABDUL ABDUL QUYYAM H/NO. 37 ST NO. 31 KOT KHAWAJA SAEED 19-12- BA 13/7/2014 QUYYAM FAZAL PURA LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 1979 7 21327 MUNAWAR MUHAMMAD LATIF HOWAL SHAFI LADIES CLINICNISHTER TOWN 11/8/1952 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SULTANA DROGH WALA, LAHORE, PUNJAB 8 29370 MUHAMMAD AMIN MUHAMMAD BILAL TAION BHADIA ROAD, LAHORE, PUNJAB 25-3-1966 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SADIQ 9 29077 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD ST. NO. 3 NAJAM PARK SHADI PURA BUND 9-8-1983 MATRIC 13/07/2014 ABBAS ATAREE TUFAIL QAREE ROAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 10 26461 MIRZA IJAZ BAIG MIRZA MEHMOOD PST COLONY Q 75-H MULTAN ROAD LHR , 22-2-1961 MA 13/07/2014 BAIG LAHORE, PUNJAB 11 32790 AMATUL JAMEEL ABDUL LATIF H/NO. -

Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: a Study Of

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 19, Issue 1 1995 Article 5 Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud∗ ∗ Copyright c 1995 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud Abstract Pakistan’s successive constitutions, which enumerate guaranteed fundamental rights and pro- vide for the separation of state power and judicial review, contemplate judicial protection of vul- nerable sections of society against unlawful executive and legislative actions. This Article focuses upon the remarkably divergent pronouncements of Pakistan’s judiciary regarding the religious status and freedom of religion of one particular religious minority, the Ahmadis. The superior judiciary of Pakistan has visited the issue of religious freedom for the Ahmadis repeatedly since the establishment of the State, each time with a different result. The point of departure for this ex- amination is furnished by the recent pronouncement of the Supreme Court of Pakistan (”Supreme Court” or “Court”) in Zaheeruddin v. State,’ wherein the Court decided that Ordinance XX of 1984 (”Ordinance XX” or ”Ordinance”), which amended Pakistan’s Penal Code to make the public prac- tice by the Ahmadis of their religion a crime, does not violate freedom of religion as mandated by the Pakistan Constitution. This Article argues that Zaheeruddin is at an impermissible variance with the implied covenant of freedom of religion between religious minorities and the Founding Fathers of Pakistan, the foundational constitutional jurisprudence of the country, and the dictates of international human rights law. -

Report on Citizenship Law:Pakistan

CITIZENSHIP COUNTRY REPORT 2016/13 REPORT ON DECEMBER CITIZENSHIP 2016 LAW:PAKISTAN AUTHORED BY FARYAL NAZIR © Faryal Nazir, 2016 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. EUDO Citizenship Observatory Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies in collaboration with Edinburgh University Law School Report on Citizenship Law: Pakistan RSCAS/EUDO-CIT-CR 2016/13 December 2016 © Faryal Nazir, 2016 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), created in 1992 and directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. The Centre is home to a large post-doctoral programme and hosts major research programmes, projects and data sets, in addition to a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration, the expanding membership of the European Union, developments in Europe’s neighbourhood and the wider world. -

How Post 9/11 Pakistani English Literature Speaks to the World

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 11-17-2017 2:00 PM Terrorism, Islamization, and Human Rights: How Post 9/11 Pakistani English Literature Speaks to the World Shazia Sadaf The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Julia Emberley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Shazia Sadaf 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Literature in English, Anglophone outside British Isles and North America Commons Recommended Citation Sadaf, Shazia, "Terrorism, Islamization, and Human Rights: How Post 9/11 Pakistani English Literature Speaks to the World" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5055. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5055 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Terrorism, Islamization, and Human Rights: How Post 9/11 Pakistani English Literature Speaks to the World Abstract The start of the twenty-first century has witnessed a simultaneous rise of three areas of scholarly interest: 9/11 literature, human rights discourse, and War on Terror studies. The resulting intersections between literature and human rights, foregrounded by an overarching narrative of terror, have led to a new area of interdisciplinary enquiry broadly classed under human rights literature, at the point of the convergence of which lies the idea of human empathy.