Document Resume Ed 214 449 He 014 901 Author Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Practices of Literacy: a Case of Costa Rica Final Report for the Spencer Foundation1

Cultural Practices of Literacy: A Case of Costa Rica Final Report for the Spencer Foundation1 Victoria Purcell-Gates, Ph.D. Canada Research Chair – Early Childhood Literacy University of British Columbia Focus of Study In cooperation with officials from the Costa Rican Ministry of Public Education, I conducted a six-month ethnography in Costa Rica, from January 1, 2006 – June 30, 2006. One focus of the research was to explore factors that may account for many of the difficulties that are experienced by poor and marginalized children in the Costa Rican Schools, particularly those of Nicaraguan immigrants. This focus reflects the primary interest of education officials in Costa Rica. The second focus of the study was to come to deeper understandings of the relationships of young children’s community-based literacy practices and their ways of learning from early literacy instruction in school, one of the central goals of my larger project, Cultural Practices of Literacy Study (CPLS) (Purcell-Gates, in press). This latter I view as key to much –needed theorizing of social and cultural marginality as it relates to academic achievement. I focused exclusively on the early literacy learning of the children primarily because high rates of first-grade retention is considered to be a problem in the Costa Rican schools and because the success in first stages of learning to read and write determines the level of success at learning in other subjects and in the later grades. Theoretical Frame & Related Research This study of literacy in community reflects a theoretical frame of literacy as social and cultural practice (Street, 1984) that is patterned by social institutions, historical settings, values, beliefs, and power relationships (Au, 2002; Barton & Hamilton, 1998; Brandt, 2001; Fishman, 1988; Moje, 2000; Purcell-Gates, 1995, 1996; Scribner & Cole, 1981; Street 1995). -

AIB 2010 Annual Meeting Rio De Janeiro, Brazil June 25-29, 2010

AIB 2010 Annual Meeting Rio de Janeiro, Brazil June 25-29, 2010 Registered Attendees For The 2010 Meeting The alphabetical list below shows the final list of registered delegates for the 2010 AIB Annual Conference in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Final Registrant Count: 895 A Esi Abbam Elliot, University of Illinois, Chicago Ashraf Abdelaal Mahmoud Abdelaal, University of Rome Tor vergata Majid Abdi, York University (Institutional Member) Monica Abreu, Universidade Federal do Ceara Kofi Afriyie, New York University Raj Aggarwal, The University of Akron Ruth V. Aguilera, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Yair Aharoni, Tel Aviv University Niklas Åkerman, Linneaus School of Business and Economics Ian Alam, State University of New York Hadi Alhorr, Saint Louis University Andreas Al-Laham, University of Mannheim Gayle Allard, IE University Helena Allman, University of South Carolina Victor Almeida, COPPEAD / UFRJ Patricia Almeida Ashley,Universidade Federal Fluminense Ilan Alon, Rollins College Marcelo Alvarado-Vargas, Florida International University Flávia Alvim, Fundação Dom Cabral Mohamed Amal, Universidade Regional de Blumenau- FURB Marcos Amatucci, Escola Superior de Propaganda e Marketing de SP Arash Amirkhany, Concordia University Poul Houman Andersen, Aarhus University Ulf Andersson, Copenhagen Business School Naoki Ando, Hosei University Eduardo Bom Angelo,LAZAM MDS Madan Annavarjula, Bryant University Chieko Aoki,Blue Tree Hotels Masashi Arai, Rikkyo University Camilo Arbelaez, Eafit University Harvey Arbeláez, Monterey Institute -

Education in Costa Rica

Education in Costa Rica HIGHLIGHTS 2017 Costa Rica WHAT ARE REVIEWS OF NATIONAL POLICIES FOR a strong focus on improving learning outcomes; equity in EDUCATION? educational opportunity; the ability to collect and use data to inform policy; the effective use of funding to steer reform; OECD Education Policy Reviews provide tailored advice and the extent of multistakeholder engagement in policy to governments to develop policies that improve the skills design and implementation. of all members of society, and ensure that those skills are used effectively, to promote inclusive growth for better jobs Based on these tough benchmarks, the review both underlines and better lives. The OECD works with countries to identify the many strengths of Costa Rica’s education system and and understand the factors behind successful reform and provides recommendations on how to improve policies and provide direct support to them in designing, adopting and practices so that the country can advance towards OECD implementing reforms in education and skills policies. standards of education attainment and outcomes. These highlights summarise the main findings of the Review: WHY A REVIEW OF EDUCATION IN COSTA RICA? l Early childhood education: Higher priority should be given higher priority in public spending and policy, given the In 2015, the OECD opened discussions for the accession of vital role it can play in tackling disadvantage and poverty. Costa Rica to the OECD Convention. As part of this process, Costa Rica has undergone in-depth reviews in all the relevant l Basic education: The quality and equity of learning areas of the Organisation’s work including a comprehensive outcomes should become the centre point of policy and review of the education system, from early childhood practice. -

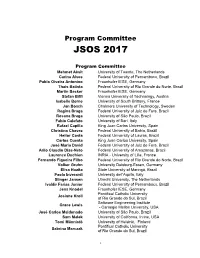

JSOS 2017 Program Committee

Program Committee JSOS 2017 Program Committee Mehmet Aksit University of Twente, The Netherlands Carina Alves Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil Pablo Oiveira Antonino Fraunhofer IESE, Germany Thais Batista Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil Martin Becker Fraunhofer IESE, Germany Stefan Biffl Vienna University of Technology, Austria Isabelle Borne University of South Brittany, France Jan Bosch Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden Regina Braga Federal University of Juiz de Fora, Brazil Rosana Braga University of São Paulo, Brazil Fabio Calefato University of Bari, Italy Rafael Capilla King Juan Carlos University, Spain Christina Chavez Federal University of Bahia, Brazil Heitor Costa Federal University of Lavras, Brazil Carlos Cuesta King Juan Carlos University, Spain José Maria David Federal University of Juiz de Fora, Brazil Arilo Claudio Dias-Neto Federal University of Amazonas, Brazil Laurence Duchien INRIA - University of Lille, France Fernando Figueira Filho Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil Volker Gruhn University Duisburg-Essen, Germany Elisa Huzita State University of Maringá, Brazil Paola Inverardi University dell'Aquila, Italy Slinger Jansen Utrecht University, The Netherlands Ivaldir Farias Junior Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil Jens Knodel Fraunhofer IESE, Germany Pontifical Catholic University Josiane Kroll of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil Software Engineering Institute Grace Lewis - Carnegie Mellon University, USA José Carlos Maldonado University of São Paulo, Brazil Sam Malek -

World Bank Document

PROJECT INFORMATION DOCUMENT (PID) APPRAISAL STAGE Report No.: AB169 CR EQUITY AND EFFICIENCY OF EDUCATION Project Name Public Disclosure Authorized Region LATIN AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN Sector General education sector (100%) Project ID P057857 Borrower(s) Government of Costa Rica Implementing Agency Ministry of Public Education Environment Category [ ] A [X] B [ ] C [ ] FI [ ] TBD (to be determined) Safeguard Classification [ ] S1 [X] S2 [ ] S3 [ ] SF [ ] TBD (to be determined) Date PID Prepared December 30, 2003 Date of Appraisal February 4, 2004 Authorization Date of Board Approval May 4, 2004 Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Country and Sector Background Key elements of Costa Rica Education Sector Strategy and Implementation Instruments. Costa Rica seeks to improve the quality, equity and efficiency of education at all levels. Specific sector goals include: (i) increasing early childhood care and education (ECCE) for ages 0-5; (ii) universalizing at least one year of preschool (for 6 year-old children); (iii) universalizing primary education completion with quality of learning; and (iii) expanding nationwide secondary education (both academic and vocational) with quality. These specific goals will be achieved with keen focus on equity—by targeting education services to traditionally underserved populations (including rural communities and ethnic minorities)—and with increased institutional efficiency and cost-effectiveness. While some goals are nationwide (ECCE and Public Disclosure Authorized Secondary Education), others focus on closing the gaps between regions and across income groups (preschool and finalization of quality primary education). The overarching policies of the Consejo Superior de Educación (CSE), the national body that defines education policies, orient these national educational aims: • Generating educational initiatives that increase equal access to pertinent, high quality opportunities for education and training, including universal access to preschool, increasing enrollment in secondary education, and improving quality at all levels. -

A Framework for Threat-Driven Cyber Security Verification of Iot Systems

Conference Organizers General Chairs Edson Midorikawa (Univ. de Sao Paulo - Brazil) Liria Matsumoto Sato (Univ. de Sao Paulo - Brazil) Program Committee Chairs Ricardo Bianchini (Rutgers University - USA) Wagner Meira Jr. (Univ. Federal de Minas Gerais - Brazil) Steering Committee Alberto F. De Souza (UFES, Brazil) Claudio L. Amorim (UFRJ, Brazil) Edson Norberto Cáceres (UFMS, Brazil) Jairo Panetta (INPE, Brazil) Jean-Luc Gaudiot (UCI, USA) Liria M. Sato (USP, Brazil) Philippe O. A. Navaux (UFRGS, Brazil) Rajkumar Buyya Universidade de Melbourne, Australia) Siang W. Song (USP, Brazil) Viktor Prasanna (USC, USA) Vinod Rabello (UFF, Brazil) Walfredo Cirne (Google, USA) Organizing Committee Artur Baruchi (USP-Brazil) Calebe de Paula Bianchini (Mackenzie – Brazil) Denise Stringhini (Mackenzie – Brazil) Edson Toshimi Midorikawa (USP-Brazil) Francisco Isidro Massetto (USP-Brazil) Gabriel Pereira da Silva (UFRJ - Brazil) Hélio Crestana Guardia (UFSCar – Brazil) Francisco Ribacionka (USP-Brazil) Hermes Senger (UFSCar – Brazil) Liria Matsumoto Sato (USP-Brazil) Ricardo Bianchini (Rutgers University - USA) Wagner Meira Jr. (UFMG - Brazil) Program Committee Alfredo Goldman vel Lejbman (USP-Brazil) Ismar Frango Silveira (Mackenzie-Brazil) Nicolas Kassalias (USJT-Brazil) x Computer Architecture Track Vice-chair: David Brooks (Harvard) Claudio L. Amorim (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro) Nader Bagherzadeh (University of California at Irvine) Mauricio Breternitz Jr. (Intel) Patrick Crowley (Washington University) Cesar De Rose (PUC Rio Grande do Sul) Alberto Ferreira De Souza (Federal University of Espirito Santo) Jean-Luc Gaudiot (University of California at Irvine) Timothy Jones (University of Edinburgh) David Kaeli (Northeastern University) Jose Moreira (IBM Research) Philippe Navaux (Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul) Yale Patt (University of Texas at Austin) Gabriel P. -

Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira: Representação Interinstitucional E

1 - EDITORIAL Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira Representação interinstitucional e interdisciplinar Alberto GoldenbergI, Tânia Pereira Morais FinoII Saul GoldenbergIII, I Editor Científico Acta Cir Bras II Secretaria Acta Cir Bras III Fundador e Editor Chefe Acta Cir Bras Em editorial no fascículo no 1, janeiro-fevereiro de 2009, o número de artigos do exterior e o número de suplementos no apresentou-se o desempenho da Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira referentes período. aos anos de 1986 a 20001 e de 2001 a 20052, nos quais se destacava Decidimos investigar a participação interinstitucional e a distribuição geográfica dos autores, o número de artigos nacionais, interdisciplinar da revista nos anos de 2007 e 2008. ORIGEM INSTITUCIONAL DOS ARTIGOS INSTITUIÇÕES NACIONAIS Bahia Experimental Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of Bahia[UFBA] Operative Technique and Experimental Surgery, Bahia School of Medicine Brasília Laboratory of Experimental Surgery, School of Medicine, University of Brasilia, Brazil. Ceará Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of Ceará. Experimental Surgical Research Laboratory, Department of Surgery, Federal Univesity of Ceará, Brazil. Espírito Santo Laboratory Division of Surgical Principles, Department of Surgery, School of Sciences, Espirito Santo. Goiás Department of Veterinary Medicine, Veterinary Medicine College, Federal University of Goiás. Maranhão Experimental Research, Department of Surgery, Federal University of Maranhão Mato Grosso Department of Surgery,Federal University of Mato Grosso[UFMT] Mato Grosso do Sul Laboratory of Research, Mato Grosso do Sul Federal University Minas Gerais Department of Surgery, Experimental Laboratory, School of Medicine, Federal University of Minas Gerais Laboratory of Apoptosis, Department of General Pathology, Institute of Biological Science, Federal University of Minas Gerais Wild Animals Research Laboratory, Federal University of Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brazil. -

Brazil Academic Webuniverse Revisited: a Cybermetric Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-LIS Brazil academic webuniverse revisited: A cybermetric analysis 1 ISIDRO F. AGUILLO 1 JOSÉ L. ORTEGA 1 BEGOÑA GRANADINO 1 CINDOC-CSIC. Joaquín Costa, 22. 28002 Madrid. Spain {isidro;jortega;bgranadino}@cindoc.csic.es Abstract The analysis of the web presence of the universities by means of cybermetric indicators has been shown as a relevant tool for evaluation purposes. The developing countries in Latin-American are making a great effort for publishing electronically their academic and scientific results. Previous studies done in 2001 about Brazilian Universities pointed out that these institutions were leaders for both the region and the Portuguese speaking community. A new data compilation done in the first months of 2006 identify an exponential increase of the size of the universities’ web domains. There is also an important increase in the web visibility of these academic sites, but clearly of much lower magnitude. After five years Brazil is still leader but it is not closing the digital divide with developed world universities. Keywords: Cybermetrics, Brazilian universities, Web indicators, Websize, Web visibility 1. Introduction. The Internet Lab (CINDOC-CSIC) has been working on the development of web indicators for the Latin-American academic sector since 1999 (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8). The region is especially interesting due to the presence of several very large developing countries that are perfect targets for case studies and the use of Spanish and Portuguese languages in opposition to English usually considered the scientific “lingua franca”. -

The Pilotis As Sociospatial Integrator: the Urban Campus of the Catholic University of Pernambuco

1665 THE PILOTIS AS SOCIOSPATIAL INTEGRATOR: THE URBAN CAMPUS OF THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF PERNAMBUCO Robson Canuto da Silva Universidade Católica de Pernambuco [email protected] Maria de Lourdes da Cunha Nóbrega Universidade Católica de Pernambuco [email protected] Andreyna Raphaella Sena Cordeiro de Lima Universidade Católica de Pernambuco [email protected] 8º CONGRESSO LUSO-BRASILEIRO PARA O PLANEAMENTO URBANO, REGIONAL, INTEGRADO E SUSTENTÁVEL (PLURIS 2018) Cidades e Territórios - Desenvolvimento, atratividade e novos desafios Coimbra – Portugal, 24, 25 e 26 de outubro de 2018 THE PILOTIS AS SOCIOSPATIAL INTEGRATOR: THE URBAN CAMPUS OF THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF PERNAMBUCO R. Canuto, M.L.C.C. Nóbrega e A. Sena ABSTRACT This study aims to investigate space configuration factors that promote patterns of pedestrian movement and social interactions on the campus of the Catholic University of Pernambuco, located in Recife, in the Brazilian State of Pernambuco. The campus consists of four large urban blocks and a number of modern buildings with pilotis, whose configuration facilitates not only pedestrian movement through the urban blocks, but also various other types of activity. The methodology is based on the Social Logic of Space Theory, better known as Space Syntax. The study is structured in three parts: (1) The Urban Campus, which presents an overview of the evolution of universities and relations between campus and city; (2) Paths of an Urban Campus, which presents a spatial analysis on two scales (global and local); and (3) The Role of pilotis as a Social Integrator, which discusses the socio-spatial role of pilotis. Space Syntax techniques (axial maps of global and local integration)1 was used to shed light on the nature of pedestrian movement and its social performance. -

Country Brief Costa Rica

INSTITUTE COUNTRY BRIEF COSTA RICA Frida Andersson, Valeriya Mechkova and Staan I. Lindberg February 2016 Country Briefs THE VARIETIES OF DEMOCRACY INSTITUTE Please address comments and/or queries for information to: V-Dem Institute Department of Political Science University of Gothenburg Sprängkullsgatan 19, PO Box 711 SE 40530 Gothenburg Sweden E-mail: [email protected] V-Dem Working Papers are available in electronic format at www.v-dem.net. Copyright © 2016 University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute. All rights reserved. Country Brief Costa Rica About V-Dem Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) is a new approach to conceptualizing and measuring democracy. V-Dem’s multidimensional and disaggregated approach acknowledges the complexity of the concept of democracy. The V-Dem project distinguishes among five high-level principles of democracy: electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian, which are disaggregated into lower-level components and specific indicators. Key features of V-Dem: Provides reliable data on five high-level principles and 22 lower-level components of democracy such as regular elections, judicial independence, direct democracy, and gender equality, consisting of more than 400 distinct and precise indicators; Covers all countries and dependent territories from 1900 to the present and provides an estimate of measurement reliability for each rating; Makes all ratings public, free of charge, through a user-friendly interface. With four Principal Investigators, two Project Coordinators, fifteen Project Managers, more than thirty Regional Managers, almost 200 Country Coordinators, several Assistant Researchers, and approximately 2,600 Country Experts, the V-Dem project is one of the largest-ever social science data collection projects with a database of over 15 million data points. -

Is a 501(C)3 Non-Profit Organization Committed to Providing International Learning Opportunities for US-Based Social Work Students

SWAP PARTICIPANT MANUAL GENERAL INFORMATION FOR PROGRAM PARTICIPANTS Social Work Abroad Program (SWAP) is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization committed to providing international learning opportunities for US-based social work students. www.socialworkabroad.org Table of Contents: About SWAP Page 2 Mission Statement Page 2 Organization and Structure of SWAP Placement/Service Learning Page 2 Selection Process Page 2 SWAP’s Professional Conduct and Performance Expectations Page 3 Participant Roles and Responsibilities Page 4 Knots and Bolts Page 6 What to Pack Page 9 Living with a Family Page 12 Costa Rica Projects Page 15 Background Information on Costa Rica Page 17 SWAP Re-entry Support Page 20 1 ABOUT SWAP Social Work Abroad Program SWAP is a 501 c 3 non-profit organization, is the vision of social workers who are committed to providing international learning opportunities for US-based social work students. Participants are able to practice and exchange ideas in an international setting which promotes compassion, cultural sensitivity, effective practice and competency. MISSION STATEMENT SWAP’s mission is to provide enriched, supported, intercultural internships for US social work students who transform both personally and professionally, through meaningful exchange. SWAP further seeks to enhance US social workers knowledge of international social work in order to foster global citizenship. Vision: Transforming social workers into global citizens. ORGANIZATION AND STRUCTURE OF SWAP PLACEMENT/SERVICE LEARNING The field placement/service learning is the heart of SWAP. The experience offered by SWAP is an opportunity for participants to integrate and apply theoretical knowledge and social work practice and intervention skills in an international setting under the supervision of SWAP Facilitators. -

Education for a Sustainable Future: Analysis of the Educational System in Osa and Golfito

This document is a part of The Osa and Golfito Initiative, Education for a sustainable future: Analysis of the educational system in Osa and Golfito M.Sc. Claire Menke Anthropology, Stanford University Professor Martin Carnoy, Ph.D. Graduate School of Education, Stanford University San José, Costa Rica July, 2013 “Education for a sustainable future: Analysis of the educational system in Osa and Golfito” M.Sc. Claire Menke Anthropology Professor Martin Carnoy, Ph.D. Graduate School of Education Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment Stanford University This document is part of: Iniciativa Osa y Golfito, INOGO Stanford, California Julio de 2013 Citation: Menke, Claire and Martin Carnoy. 2013. Education for a sustainable future: Analysis of the educational system in Osa and Golfito. Stanford, California: INOGO, Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, July 2013. 2 Contents Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Osa and Golfito Initiative Overview ............................................................................................... 5 What is INOGO .................................................................................................................................................. 5 The INOGO Study Region .............................................................................................................................. 7 Executive summary ............................................................................................................................