Pine and Curry Island Ocieni'ific and Na'iural Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Chapter 85

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 85.011 CHAPTER 85 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION STATE PARKS, RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES 85.06 SCHOOLHOUSES IN CERTAIN STATE PARKS. 85.011 CONFIRMATION OF CREATION AND 85.20 VIOLATIONS OF RULES; LITTERING; PENALTIES. ESTABLISHMENT OF STATE PARKS, STATE 85.205 RECEPTACLES FOR RECYCLING. RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES. 85.21 STATE OPERATION OF PARK, MONUMENT, 85.0115 NOTICE OF ADDITIONS AND DELETIONS. RECREATION AREA AND WAYSIDE FACILITIES; 85.012 STATE PARKS. LICENSE NOT REQUIRED. 85.013 STATE RECREATION AREAS AND WAYSIDES. 85.22 STATE PARKS WORKING CAPITAL ACCOUNT. 85.014 PRIOR LAWS NOT ALTERED; REVISOR'S DUTIES. 85.23 COOPERATIVE LEASES OF AGRICULTURAL 85.0145 ACQUIRING LAND FOR FACILITIES. LANDS. 85.0146 CUYUNA COUNTRY STATE RECREATION AREA; 85.32 STATE WATER TRAILS. CITIZENS ADVISORY COUNCIL. 85.33 ST. CROIX WILD RIVER AREA; LIMITATIONS ON STATE TRAILS POWER BOATING. 85.015 STATE TRAILS. 85.34 FORT SNELLING LEASE. 85.0155 LAKE SUPERIOR WATER TRAIL. TRAIL PASSES 85.0156 MISSISSIPPI WHITEWATER TRAIL. 85.40 DEFINITIONS. 85.016 BICYCLE TRAIL PROGRAM. 85.41 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI PASSES. 85.017 TRAIL REGISTRY. 85.42 USER FEE; VALIDITY. 85.018 TRAIL USE; VEHICLES REGULATED, RESTRICTED. 85.43 DISPOSITION OF RECEIPTS; PURPOSE. ADMINISTRATION 85.44 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI TRAIL GRANT-IN-AID 85.019 LOCAL RECREATION GRANTS. PROGRAM. 85.021 ACQUIRING LAND; MINNESOTA VALLEY TRAIL. 85.45 PENALTIES. 85.04 ENFORCEMENT DIVISION EMPLOYEES. 85.46 HORSE -

The Campground Host Volunteer Program

CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM THE CAMPGROUND HOST VOLUNTEER PROGRAM MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 1 CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. Addresses are listed at the back of this brochure. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Recreation 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 651-259-5607 [email protected] Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. Volunteers will set an example by being model campers, practicing good housekeeping at all times in and around the host site, and by observing all rules. -

Minnesota State Parks.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Afton State Park 4 2. Banning State Park 6 3. Bear Head Lake State Park 8 4. Beaver Creek Valley State Park 10 5. Big Bog State Park 12 6. Big Stone Lake State Park 14 7. Blue Mounds State Park 16 8. Buffalo River State Park 18 9. Camden State Park 20 10. Carley State Park 22 11. Cascade River State Park 24 12. Charles A. Lindbergh State Park 26 13. Crow Wing State Park 28 14. Cuyuna Country State Park 30 15. Father Hennepin State Park 32 16. Flandrau State Park 34 17. Forestville/Mystery Cave State Park 36 18. Fort Ridgely State Park 38 19. Fort Snelling State Park 40 20. Franz Jevne State Park 42 21. Frontenac State Park 44 22. George H. Crosby Manitou State Park 46 23. Glacial Lakes State Park 48 24. Glendalough State Park 50 25. Gooseberry Falls State Park 52 26. Grand Portage State Park 54 27. Great River Bluffs State Park 56 28. Hayes Lake State Park 58 29. Hill Annex Mine State Park 60 30. Interstate State Park 62 31. Itasca State Park 64 32. Jay Cooke State Park 66 33. John A. Latsch State Park 68 34. Judge C.R. Magney State Park 70 1 35. Kilen Woods State Park 72 36. Lac qui Parle State Park 74 37. Lake Bemidji State Park 76 38. Lake Bronson State Park 78 39. Lake Carlos State Park 80 40. Lake Louise State Park 82 41. Lake Maria State Park 84 42. Lake Shetek State Park 86 43. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

2011 Project Abstract for the Period Ending June 30, 2012

2011 Project Abstract For the Period Ending June 30, 2012 PROJECT TITLE: Minnesota County Biological Survey PROJECT MANAGER: Carmen Converse AFFILIATION: MN DNR MAILING ADDRESS: 500 Lafayette Rd CITY/STATE/ZIP: St Paul, MN 55155 PHONE: (651) 259-5083 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/eco/mcbs/index.html FUNDING SOURCE: Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund) LEGAL CITATION: M.L. 2011, First Special Session, Chp. 2, Art.3, Sec. 2, Subd. 03a APPROPRIATION AMOUNT: $2,250,000 Overall Project Outcome and Results: The need to protect and manage functional ecological systems, including ecological processes and component organisms continues to accelerate with increased demands for water and energy, continued habitat fragmentation, loss of species and genetic diversity, invasive species expansion, and changing environmental conditions. Since 1987 the Minnesota County Biological Survey (MCBS) has systematically collected, interpreted and delivered baseline data on the distribution and ecology of plants, animals, native plant communities, and functional landscapes. These data help prioritize actions to conserve and manage Minnesota's ecological systems and critical components of biological diversity. During this project period baseline surveys continued, focused largely in northern Minnesota (see map). One highlight was data collection in remote areas of the patterned peatlands that included three helicopter-assisted field surveys coordinated with other researchers to increase the knowledge of this ecological system and to continue long-term collaborative monitoring. Another goal was to begin monitoring to measure the effectiveness of management and policy activities. For example, prairie vegetation and small white lady’s slipper monitoring began in western Minnesota sites in response to ecological measures identified in the Minnesota Prairie Conservation Plan 2010. -

Minnesota in Profile

Minnesota in Profile Chapter One Minnesota in Profile Minnesota in Profile ....................................................................................................2 Vital Statistical Trends ........................................................................................3 Population ...........................................................................................................4 Education ............................................................................................................5 Employment ........................................................................................................6 Energy .................................................................................................................7 Transportation ....................................................................................................8 Agriculture ..........................................................................................................9 Exports ..............................................................................................................10 State Parks...................................................................................................................11 National Parks, Monuments and Recreation Areas ...................................................12 Diagram of State Government ...................................................................................13 Political Landscape (Maps) ........................................................................................14 -

Campground Host Program

Campground Host Program MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF PARKS AND TRAILS Updated November 2010 Campground Host Program Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. You may email your completed application to [email protected] who will forward it to your first choice park. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Trails 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 Email: [email protected] 651-259-5607 Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. -

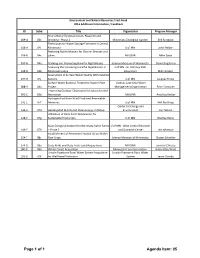

Of 1 Agenda Item: 05 ENRTF ID: 009-A / Subd

Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund 2016 Additional Information / Feedback ID Subd. Title Organization Program Manager Prairie Butterfly Conservation, Research and 009‐A 03c Breeding ‐ Phase 2 Minnesota Zoological Garden Erik Runquist Techniques for Water Storage Estimates in Central 018‐A 04i Minnesota U of MN John Neiber Restoring Native Mussels for Cleaner Streams and 036‐B 04c Lakes MN DNR Mike Davis 037‐B 04a Tracking and Preventing Harmful Algal Blooms Science Museum of Minnesota Daniel Engstrom Assessing the Increasing Harmful Algal Blooms in U of MN ‐ St. Anthony Falls 038‐B 04b Minnesota Lakes Laboratory Miki Hondzo Assessment of Surface Water Quality With Satellite 047‐B 04j Sensors U of MN Jacques Finlay Surface Water Bacterial Treatment System Pilot Vadnais Lake Area Water 088‐B 04u Project Management Organization Brian Corcoran Improving Outdoor Classrooms for Education and 091‐C 05b Recreation MN DNR Amy Kay Kerber Hydrogen Fuel from Wind Produced Renewable 141‐E 07f Ammonia U of MN Will Northrop Center for Energy and 144‐E 07d Geotargeted Distributed Clean Energy Initiative Environment Carl Nelson Utilization of Dairy Farm Wastewater for 148‐E 07g Sustainable Production U of MN Bradley Heins Solar Energy Utilization for Minnesota Swine Farms U of MN ‐ West Central Research 149‐E 07h – Phase 2 and Outreach Center Lee Johnston Establishment of Permanent Habitat Strips Within 154‐F 08c Row Crops Science Museum of Minnesota Shawn Schottler 174‐G 09a State Parks and State Trails Land Acquisitions MN DNR Jennifer Christie 180‐G 09e Wilder Forest Acquisition Minnesota Food Association Hilary Otey Wold Lincoln Pipestone Rural Water System Acquisition Lincoln Pipestone Rural Water 181‐G 09f for Well Head Protection System Jason Overby Page 1 of 1 Agenda Item: 05 ENRTF ID: 009-A / Subd. -

2013 Hunting & Trapping Regulations

2013 Minnesota REGULATIONS HANDBOOK mndnr.gov 888-646-6367 651-296-6157 24-hour tip hotline: 800-652-9093 dial #tip for at&t, midwest wireless, unicel, and verizon 2013 Minnesota Hunting Regulations WELCOME TO THE 2013 MINNESOTA HUNTING SEASONS. New regulations are listed below. Have a safe and enjoyable hunt. NEW NEW REGULATIONS FOR 2013 Licensing • Apprentice Hunter validations are now available to non-residents. See pages 13 and 18. • All deer license buyers, including archery hunters, will be asked which area they hunt most often when they purchase a license. !is is for information only and does not obligate the hunter to remain in the area indicated. • Age requirement changes for a youth licenses are noted on pages 10-15 for turkey, deer, and bear. • Small game license are no longer required for youth under age 16. • Starting August 1 license agents will charge $1 issuing fee for lottery, free licenses, and applications. • Some hunting and fishing licenses can be purchased using a mobile device. An electronic copy of the license will be sent by email or text, which must be provided to an enforcement officer upon request. Not all licenses will be available, including those that require tags. Go to mndnr.gov/BuyALicense Trapping/Furbearers !e bag limit for fisher and marten is now two combined (one fisher and one marten or two fisher or two marten). Prairie chickens !e prairie chicken season is open Sept. 28-Oct. 6 and some permit area boundaries have changed. See http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/hunting/prai- riechicken/index.html Bear hunting • Bears can now be registered online or by phone, but hunters must still submit a tooth sample. -

Garden Island SRA

GARDEN ISLAND STATE RECREATION MAP LEGEND AREA Boat Docks FACILITIES AND FEATURES Picnic Area • Safe harbor Shelter • Boat docking • Picnic area Lake of the Woods Toilet • Fire rings Bald Eagle Nest •Toilets • Shelter Beaver Lodge Distances to Garden Island from: GARDEN Private Property VISITOR FAVORITIES Public Use Prohibited • Shore lunch Zippel Bay ....................................21 miles Long Point....................................15 miles • Beach walking State Park Land Rocky Point ..................................18 miles State Park Open to Hunting • Fishing Warroad ........................................28 miles Land Open •Swimming Wheeler’s Point ...........................24 miles to Hunting • Boating Oak Island ....................................10 miles ISLAND RED LAKE •Hiking Young’s Bay..................................15 miles INDIAN Falcon Bay • Birdwatching Angle Inlet....................................19 miles RESERVATION • Snowmobiling PENASSE S. R. A. No Hunting SPECIAL FEATURES ANGLE INLET Young’s • Nesting bald eagles Bay OAK ISLAND • Spectacular beaches NORTHWEST ANGLE STATE FOREST Garden Big Island Island Starren Lake of the Woods Lake of the Woods Shoals Long Point Rocky Point 313 ROAD LUDE AR W ARNESON17 ZIPPEL BAY 12 STATE PARK 8 WHEELER'SPOINT SWIFT 8 LOOKING FOR MORE INFORMATION ? 2 172 4 The DNR has mapped the state showing federal, NORTH state and county lands with their recreational OOSEVELT RAINY facilities. R 11 6 RIVER Public Recreation Information Maps (PRIM) are WILLIAMS available for purchase from the DNR gift shop, DNR Because lands exist within the boundaries 0 .1 .2 .3 .4 .5 1 Miles regional offices, Minnesota state parks and major GRACETON PITT of this park that are not under the jurisdiction sporting and map stores. of the D.N.R., check with the park manager Vicinity Map BAUDETTE 72 if you plan to use facilities such as trails and Check it out - you'll be glad you did. -

Special Places

UMMER ULY S 2017 (J ) Special Places PARKS & TRAILS COUNCIL OF MINNESOTA NEWSLETTER ers My ifer Jenn Big Bog State Rec Area by Inside this issue LETTER FROM BRETT .............................PG 2 TRAIL COUNTERS GO UP .....................PG 3 LEGISLATIVE RECAP ...........................PG 4-5 NOISE ...................................................PG 6 ST. CROIX SP PLAN ...............................PG 6 MILL TOWNS TRAIL OPENS ..................PG 7 DR. DOROTHY ANDERSON ..................PG 8 FRONTENAC & FRIENDS ................... PG 11 rd 3 Annual Atop bluff Parks & Trails Council acquired for Frontenac with lakelet leading into Lake Pepin. Photo Contest! Land Project Update Enter thru Aug. 20, 2017 3 CATEGORIES Adding a new view to Frontenac State Park t the entrance to Frontenac State of this land’s natural beauty, you would Park lays 161.33 acres of land need to climb its blu, which looks thatA has been a farm, a (unsanctioned) out in the opposite direction from landll and an explosion reenact- park’s famous Lake Pepin overlooks. ment testing grounds. Yet, its scenic From atop the newly acquired, peace- vistas and proximity to the state park ful blu you will see the meandering foreshadowed other uses. In May the waters of the lakelet and creek that fate of this land was sealed as Parks & wrap around the southern end of the Trails Council purchased it to become park and ow into Lake Pepin. part of the park. is view (photo above) is what If you’ve ever visited the park you’ve captured the attention of Parks & glimpsed this land, which is along Trails Council’s then president Mike $300 in prizes for 1st - 3rd places Highway 2, just north of the bridge Tegeder as he visited with members of See all the entries & submit your photos at crossing the Pleasant Valley Lakelet the Frontenac State Park Association www.parksandtrails.org and Creek. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G4127 NORTHWESTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G4127 FEATURES, ETC. .C8 Custer National Forest .L4 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail .L5 Little Missouri River .M3 Madison Aquifer .M5 Missouri River .M52 Missouri River [wild & scenic river] .O7 Oregon National Historic Trail. Oregon Trail .W5 Williston Basin [geological basin] .Y4 Yellowstone River 1305 G4132 WEST NORTH CENTRAL STATES. REGIONS, G4132 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .D4 Des Moines River .R4 Red River of the North 1306 G4142 MINNESOTA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G4142 .A2 Afton State Park .A4 Alexander, Lake .A42 Alexander Chain .A45 Alice Lake [Lake County] .B13 Baby Lake .B14 Bad Medicine Lake .B19 Ball Club Lake [Itasca County] .B2 Balsam Lake [Itasca County] .B22 Banning State Park .B25 Barrett Lake [Grant County] .B28 Bass Lake [Faribault County] .B29 Bass Lake [Itasca County : Deer River & Bass Brook townships] .B3 Basswood Lake [MN & Ont.] .B32 Basswood River [MN & Ont.] .B323 Battle Lake .B325 Bay Lake [Crow Wing County] .B33 Bear Head Lake State Park .B333 Bear Lake [Itasca County] .B339 Belle Taine, Lake .B34 Beltrami Island State Forest .B35 Bemidji, Lake .B37 Bertha Lake .B39 Big Birch Lake .B4 Big Kandiyohi Lake .B413 Big Lake [Beltrami County] .B415 Big Lake [Saint Louis County] .B417 Big Lake [Stearns County] .B42 Big Marine Lake .B43 Big Sandy Lake [Aitkin County] .B44 Big Spunk Lake .B45 Big Stone Lake [MN & SD] .B46 Big Stone Lake State Park .B49 Big Trout Lake .B53 Birch Coulee Battlefield State Historic Site .B533 Birch Coulee Creek .B54 Birch Lake [Cass County : Hiram & Birch Lake townships] .B55 Birch Lake [Lake County] .B56 Black Duck Lake .B57 Blackduck Lake [Beltrami County] .B58 Blue Mounds State Park .B584 Blueberry Lake [Becker County] .B585 Blueberry Lake [Wadena County] .B598 Boulder Lake Reservoir .B6 Boundary Waters Canoe Area .B62 Bowstring Lake [Itasca County] .B63 Boy Lake [Cass County] .B68 Bronson, Lake 1307 G4142 MINNESOTA.