Ielrc.Org/Content/A1008.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Claims, Histories, Meanings: Indigeneity and Legal Pluralism in India

CLAIMS, HISTORIES, MEANINGS: INDIGENEITY AND LEGAL PLURALISM IN INDIA by POOJA PARMAR B.A. Hons., Panjab University, 1993 LL.B., Panjab University, 1996 LL.M., The University of British Columbia, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Law) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2012 © Pooja Parmar, 2012 Abstract This dissertation offers critical insights into issues of access to justice by tracing the gains and losses in meaning across multiple accounts of a dispute that began with Adivasi protests against Hindustan Coca‐Cola Beverages Private Ltd. in a village in Kerala in South India. A sit‐in agitation started by Adivasi residents of the area in 2002, soon after the company set up a beverage bottling plant in the middle of small hamlets and began extracting large amounts of groundwater, is now in its tenth year. The juxtaposition of the various popular, legal and Adivasi accounts of this dispute enables a closer look at the ways in which meanings change as claims originating in contested, layered histories and in the narratives of displacement and exclusion are translated into the stronger languages of social movements and the formal legal system. Much of the particular and situated meanings, critical to the Adivasis’ experience of injustice and their opposition to the operation of the Coca‐ Cola plant, have been eclipsed in the accounts of their many committed supporters, more often than not, in pursuit of justice for the Adivasis. In addition to drawing attention to the practices and processes of literal and conceptual translation, the stories presented here demonstrate that when Adivasi protests against Coca‐Cola are understood on their own terms, in the context of their lives in the place and the stories they tell, the meanings that emerge are quite different from the ones that the available popular and legal accounts convey about these protests. -

Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (Scsp) 2014-15

Government of Kerala SCHEDULED CASTE SUB PLAN (SCSP) 2014-15 M iiF P A DC D14980 Directorate of Scheduled Caste Development Department Thiruvananthapuram April 2014 Planng^ , noD- documentation CONTENTS Page No; 1 Preface 3 2 Introduction 4 3 Budget Estimates 2014-15 5 4 Schemes of Scheduled Caste Development Department 10 5 Schemes implementing through Public Works Department 17 6 Schemes implementing through Local Bodies 18 . 7 Schemes implementing through Rural Development 19 Department 8 Special Central Assistance to Scheduled C ^te Sub Plan 20 9 100% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 21 10 50% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 24 11 Budget Speech 2014-15 26 12 Governor’s Address 2014-15 27 13 SCP Allocation to Local Bodies - District-wise 28 14 Thiruvananthapuram 29 15 Kollam 31 16 Pathanamthitta 33 17 Alappuzha 35 18 Kottayam 37 19 Idukki 39 20 Emakulam 41 21 Thrissur 44 22 Palakkad 47 23 Malappuram 50 24 Kozhikode 53 25 Wayanad 55 24 Kaimur 56 25 Kasaragod 58 26 Scheduled Caste Development Directorate 60 27 District SC development Offices 61 PREFACE The Planning Commission had approved the State Plan of Kerala for an outlay of Rs. 20,000.00 Crore for the year 2014-15. From the total State Plan, an outlay of Rs 1962.00 Crore has been earmarked for Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP), which is in proportion to the percentage of Scheduled Castes to the total population of the State. As we all know, the Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP) is aimed at (a) Economic development through beneficiary oriented programs for raising their income and creating assets; (b) Schemes for infrastructure development through provision of drinking water supply, link roads, house-sites, housing etc. -

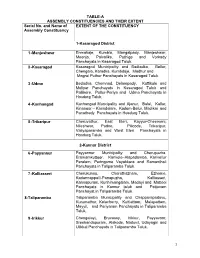

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Name of District : Palakkad Phone Numbers PS Contact LAC Name of Polling Station Name of BLO in Charge Designation Office Address NO

Palakad District BLO Name of District : Palakkad Phone Numbers PS Contact LAC Name of Polling Station Name of BLO in charge Designation Office address NO. Address office Residence Mobile Gokulam Thottazhiyam Basic School ,Kumbidi sreejith V.C.., Jr Health PHC Kumbidi 9947641618 49 1 (East) Inspector Gokulam Thottazhiyam Basic School sreejith V.C.., Jr Health PHC Kumbidi 9947641619 49 2 ,Kumbidi(West) Inspector Govt. Harigan welfare Lower Primary school Kala N.C. JPHN, PHC Kumbidi 9446411388 49 3 ,Puramathilsseri Govt.Lower Primary school ,Melazhiyam Satheesan HM GLPS Malamakkavu 2254104 49 4 District institution for Education and training Vasudevan Agri Asst Anakkara Krishi Bhavan 928890801 49 5 Aided juniour Basic school,Ummathoor Ameer LPSA AJBS Ummathur 9846010975 49 6 Govt.Lower Primary school ,Nayyur Karthikeyan V.E.O Anakkara 2253308 49 7 Govt.Basic Lower primary school,Koodallur Sujatha LPSA GBLS koodallur 49 8 Aided Juniour Basic school,Koodallur(West Part) Sheeja , JPHN P.H.C kumbidi 994611138 49 9 Govt.upper primary school ,Koodallur(West Part) Vijayalakshmi JPHN P.H.C Kumbidi 9946882369 49 10 Govt.upper primary school ,Koodallur(East Part) Vijayalakshmi JPHN P.H.C Kumbidi 9946882370 49 11 Govt.Lower Primary School,Malamakkavu(east Abdul Hameed LPSA GLPS Malamakkavu 49 12 part) Govt.Lower Primary School.Malamakkavu(west Abdul Hameed LPSA GLPS Malamakkavu 49 13 part) Moydeenkutty Memmorial Juniour basic Jayan Agri Asst Krishi bhavan 9846329807 49 14 School,Vellalur(southnorth building) Kuamaranellur Moydeenkutty Memmorial Juniour -

Perumatty Grama Panchayat V. State of Kerala, 2003

Perumatty Grama Panchayat v. State of Kerala, 2003 This document is available at ielrc.org/content/e0328.pdf For further information, visit www.ielrc.org Note: This document is put online by the International Environmental Law Research Centre (IELRC) for information purposes. This document is not an official version of the text and as such is only provided as a source of information for interested readers. IELRC makes no claim as to the accuracy of the text reproduced which should under no circumstances be deemed to constitute the official version of the document. International Environment House, Chemin de Balexert 7, 1219 Geneva, Switzerland +41 (0)22 797 26 23 – [email protected] – www.ielrc.org Case Note: Case concerning the power of the panchayat to prohibit groundwater extraction by private individuals and companies it its jurisdiction. By relying upon the Public Trust Doctrine, the Court upheld the power of the panchayat to prohibit the over- exploitation of groundwater by the Coca-Cola Company. 2004(1)KLT731 IN THE HIGH COURT OF KERALA 16.12.2003 Perumatty Grama Panchayat v. State of Kerala Hon'ble Judges: K. Balakrishnan Nair, J. JUDGMENT K. Balakrishnan Nair, J. 1. The point that arises for consideration in this case in whether a Grama Panchayat can cancel the licence of a factory manufacturing non-alcoholic beverages on the ground of excessive exploitation of ground water. The brief facts of the case are the following:- 2. The petitioner is Perumatty Grama Panchayat. The 2nd respondent Company is running a factory at Moolathara in Perumatty Grama Panchayat. Its main products are soft drinks and bottled drinking water. -

Road to Plachimada 2013

PANEL DISCUSSION REPORTS ROAD TO PLACHIMADA nd 2 September 2013 PDS_CEDL 13/001 2nd September ROAD TO PLACHIMADA 2013 The blend of environmental, developmental, sociological, economic, political and legal aspects involved in compensating the victims of Plachimada encouraged the Centre for PANEL Economy, Development and Law to conduct the discussion on the impact of Plachimada struggle and the contribution of The Plachimada Coca-Cola Victims Relief And DISCUSSION Compensation Claims Special Tribunal Bill 2011 in the Indian environmental jurisprudence. REPORT RAPPORTEURS: V P REJITHA, ROSHINI, GLITEREENA, RAHAMATH PANEL MEMBERS: DR. C R BIJOY (Activist, Independent Researcher) MR. SUJITH KOONAN (Asst. Prof., Amity Law School) ADV. RAVI PRAKASH K.P (Social Activist) DISCLAIMER: The opinions expressed herein are those of the panel members, and do not necessarily reflect those of the Centre for Economy, Development and Law, or Government Law College Thrissur or any other persons or institutions affiliated with it. Any mention of trade names, commercial products or organisation and the inclusion of advertisements, if any, published in the report does not imply a guarantee or endorsement of any kind either by the centre or the college. All reasonable precaution was taken by the rapporteurs to verify the authenticity of data and information published there in the report. The ultimate responsibility for the use and interpretation of the same lies with the panel members. Publisher, Rapporteurs and the College shall not accept any liability whatsoever in respect of any claim for damages or otherwise therefrom. PANEL DISCUSSION REPORT ON THE PLACHIMADA COCA COLA VICTIMS RELIEF AND COMPENSATION CLAIMS SPECIAL TRIBUNAL BILL, 2011 I. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Palakkad District from 01.03.2020To07.03.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Palakkad district from 01.03.2020to07.03.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Abdul Mueer.P, Ashirwad, Kalvakulam, Mission School Cr 180/2020 Bailed by 1 Sreenath.N.K krishnan.N.S 51 01.03.2020 Town South ISHO Town Koppam, Palakkad jn U/s 279 IPC Police South Cr 178/2020 Alakkal (H), Abdul Rasheed, Bailed by 2 Pramod Selvan 28 IMA Junction 01.03.2020 U/s 279 IPC & Town South Kadamkode SI of Police Police 185 MV Act Padma Sree(H), Cr 181/2020 Abdul Mueer.P, Balakrishnaa Bailed by 3 Brijesh 42 Kerala Street, SBI Junction 01.03.2020 U/s 279 IPC & Town South ISHO Town Menon Police Koppam, Palakkad 185 MV Act South Krishna Nivas, Cr 182/2020 Chirakkad, Abdul Rasheed, Bailed by 4 Anil Kumar Rajan, 41 SBI Junction 01.03.2020 U/s 279 IPC & Town South Kunathurmedu, SI of Police Police 185 MV Act Palakkad Ashif Manzil, Cr 179/2020 Near Rugmini Abdul Rasheed, Bailed by 5 Nisamudheen Abdul Samad 39 Vennakara, 01.03.2020 U/s 118(a) KP Town South Clinic SI of Police Police Noorani(po), Palakkad Act Cr 183/2020 Kannappa Varodm, Chinmaya Jothymani, SI Bailed by 6 Ramadas 59 Chakkanthara 01.03.2020 U/s 279 IPC & Town South Moothan Nagar, Palakkad of Police Police 185 MV Act Cr 177/2020 Manilikadu, Palathully, Abdul Rasheed, Bailed by 7 Jayaprakash Mani 52 Kadamkode 01.03.2020 U/s -

Kiifb Newsletter Kiifb Newsletter

KIIFB NEWSLETTER Vol 1. Issue 12.1 Defining the Future Our Chairman Shri. Pinarayi Vijayan Hon. Chief Minister Approved Projects as on 28/11/2018 Our Vice Chairman Dr. T M Thomas Isaac Hon. Minister for Finance Smt. Anie Jula Thomas, Joint Fund Manager, KIIFB handing over the first series of Pravasi Chitty Bond Certificates to Smt. M. T. Sujatha, AGM NRI Business Centre, KSFE Ltd. From the CEO’s desk.......... 4. The technicalities involved to release a Chital number, should the client be unable The highlight of the last fortnight was the auction held for the online chits for NRIs on 23rd to successfully effect the subscription in November 2018. In this issue, we would like to favour of another prospective client. trace the journey that has led to this wonderful 5. Registering the Chit with the live system of achievement. the Registration Department (CORAL) 6. Conversion of the money realized through The whole process was watched with chits into Bonds issued by KIIFB eagerness and enthusiasm by our Honourable Minister Dr. Thomas Isaac in a press meet at 7. A Financial Payment System for put Thiruvananthapuram. The Chairman, KSFE options periodically from the Bonds Shri. Peelipose Thomas and Sri. Purushothaman, issued by KIIFB so that KSFE can pay their Managing Director, KSFE were present with him commitments to Chit customers in time. along with several senior Board Members of 8. Integration of the subscription modules KSFE. There was considerable excitement in with systems of Exchange Houses the air. As our entire team watched with bated 9. Online processing for different types of breath, Ajeesh of UAE made history and became Securities the first auction winner in the lot. -

List of Notified Areas(Panchayats/Muni./Corp) Notified for Paddy ( Autumn ) Kharif 2020,2021 & 2022 Seasons

Annexure PM‐K‐I List of Notified Areas(Panchayats/Muni./Corp) Notified for Paddy ( Autumn ) Kharif 2020,2021 & 2022 Seasons Notified SL No District Block Notified Panchayat List of Villages Crops 1 AMBALAPUZHA AMBALAPUZHA (N) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 2 ALAPPUZHA MUNI. ,PUNNAPRA (N) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 3 PURAKKAD Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 4 AMBALAPUZHA (S) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 5 PUNNAPRA (S) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 6 ARYAD ARYAD ,MANNANCHERY Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 7 MUHAMMA Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 8 MARARIKULAM (S) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 9 BHARANIKKAVU MAVELIKARA (MUNI.) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 10 KANJIKUZHY CHERTHALA Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 11 CHERTHALA (S) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 12 KANJIKUZHI Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 13 THANNEERMUKKOM Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 14 KADAKKARAPPALLY Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 15 MARARIKULAM (N) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 16 PATTANAKKAD AROOR Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 17 KODAMTHURUTH Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 18 PATTANAKKAD Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 19 EZHUPUNNA Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 20 KUTHIYATHODE Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 21 THURAVOOR Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 22 VAYALAR Paddy -

Ddp-Pkd-27.04.2018

“`cW`mjþamXr`mj” C1þ 1000/2018 ]©mb¯v sU]yq«n UbIvSdm^okv, ]me¡mSv, XobXn: 27/04/2018 Ph:0491 2505374, E-Mail: [email protected] t\m«okv hnjbw : Poh-\-¡mcyw ]me-¡mSv Pnà þ ]©m-b¯v hIp-¸nse 2018 hÀjs¯ s]mXpØe-amäw At]-£-I-cpsS enÌv A´n-a-am¡n {]kn-²o-I-cn-¡p-¶p. kqN\: 1) Pn H (]n) 3/2017/D`-]h Xn¿Xn 25/02/2017 2) _lp. ]©m-b¯v Ub-d-IvS-dpsS 14/02/2018 se C1þ10/2018 mw \¼À t\m«okv 3) Cu Hm^o-knse 17/02/2018 se C1þ1000/2018 mw \¼À t\m«okv 4) Cu Hm^o-knse 10/04/2018  {]kn-²o-I-cn¨ C1þ1000/2018 mw t\m«okv {]Im-c-apÅ IcSv enÌv. ********************* kqN\ 4 {]Im-cw ]pd-s¸-Sp-hn¨ t\m«o-kn ]©m-b¯v hIp-¸n ]me-¡mSv PnÃ-bn 2018 se s]mXp-Ø-e-am-ä-¯n-\mbn, ]me-¡mSv PnÃ-bv¡p-Ån Øew amäw e`n-¡p-¶-Xn-\v At]£ kaÀ¸n-¨n-«pÅ XkvXn-I-I-fnse At]-£-I-cpsS IcSv enÌv At£-]-§Ä kzoI-cn-¡p-¶-Xn-\mbn {]kn-²o-I-cn-¡p-I-bp-m-bn. XpSÀ¶v e`n¨ At£-]- §Ä ]cn-tim-[n¨v Bh-iy-amb t`Z-K-Xn-IÄ hcp¯n ko\n-bÀ ¢mÀ¡v, ¢mÀ¡v, Hm^okv Aä³Uâv, ^pÄssSw kzo¸À apX-emb XkvXn-II-fnse s]mXp-Øeamä-¯n-\m-bpÅ At]-£-I-cpsS A´naenÌv CtXm-sSm¸w {]kn-²o-I-cn-¡p-¶p. -

Palakkad District

PALAKKAD DISTRICT RETURNING OFFICERS MUNICIPALITIES OFFICE OFFICIAL NAME & ADDRESS OF THE LB Code NAME OF LB MOBILE OFFICER(IN ENGLISH) PHONE/FAX Executive Engineer M 38 Shornur 0491-2505565 8086395113 Pwd(Roads)Palakkad Sub-Collector/Rdo Ottappalam 0466-2244323 9447704323 M 39 Ottappalam Executive Engineer Minor 0491-2522808 9995444195 Errigation Division Palakkad Deputy Director Of Economics 0491-2505106 8921666217 And Statastics Palakkad M 40 Palakkad Executive Engineer 8086395178 , 0491-2505895 Pwd(Buildings)Palakkad 9447022169 Chittur- Deputy Director Education M 41 0491-2505469 9446531820 Thathamangalam Palakkad General Manager District M 69 Pattambi 0491-2505385 9188127009 Industries Centre Palakkad District Town Planner ,Town M 70 Cherppulassery 0491-2505882 9447352780 Planning Office, Palakkad District Development officer 8547630118, M 71 Mannarkkad 0491-2505005 for Sheduled caste, Palakkad 7892103662 PALAKKAD DISTRICT RETURNING OFFICERS DISTRICT PANCHAYAT OFFICE OFFICIAL NAME & ADDRESS OF LB Code NAME OF LB MOBILE THE OFFICER(IN ENGLISH) PHONE/FAX Palakkad District D 09 District Collector Palakkad 0491-2505266 9447633445 Panchayat ` RETURNING OFFICERS BLOCK PANCHAYATS OFFICIAL NAME & ADDRESS OF OFFICE LB Code NAME OF LB MOBILE THE OFFICER(IN ENGLISH) PHONE/FAX Executive Engineer Major B 92 Thrithala 0491-2815111 9447836894 Errigation Division Palakkad Joint Director Of Co-Operative B 93 Pattambi 0491-2505529 9188118209 Audit Palakkad Deputy Director Of Dairy B 94 Ottappalam Development Department 0491-2505137 9446467244 Palakkad -

Programme Implementation Manual

KERALA LOCAL GOVERNMENT SERVICE DELIVERY PROJECT (KLGSDP) PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION MANUAL Local Self Government Department Government of Kerala India 10th February 2011 1 KERALA LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND SERVICE DELIVERY PROJECT (KLGSDP) Program Implementation Manual (PIM) Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 1. Background 8 2. Summary of Project Development Objectives 10 3. Key Project Outcomes 10 4. Summary of Project Description and Components 10-12 SECTION 1 : FINANCING AGREEMENT 1.1. Financing Agreement for the project 13-22 SECTION 2 : DETAILED PROJECT COMPONENT DESCRIPTION Project Components and Sub-components and Costs 23 (for each Component) 2.1. Component 1: Performance Grants to Gram Panchayats and Municipalities 2.1.1. Objective 23 2.1.2. Establishment of Grant 23 2.1.3. Allocation formula and funding levels 24 2.1.4. Additionality 24 2.1.5. Use of Grant Funds 24 2.1.6. Budgeting, Planning and Execution 25 2.1.7. Reporting 25 2.1.8. Phasing in of the Grant 26 2.1.9. Procedures for allocation of Grant under Phase-1 26 Grant Access Criteria 26 Grant Allocation Announcement 27 Grant Release and Receipt 27 Grant Cycle 27 2.1.10. Procedures for allocation of Grant under Phase-2 28 Access Criteria and Performance Criteria 28 Table 2.2 Mandatory Minimum Conditions and 28 Performance Criteria for accessing Grant in Phase 2 Indicative Grant allocation Announcement 29 Grant Release and Receipt 30 Grant Cycle for Phase 2 30 2.1.11. Audit Eligibility Criteria for Local Bodies 30 2.1.12. Disbursement 32 2.1.13. Sub-project Implementation 33 2.1.14.