0.0. Kalinyuk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Apocalyptic Book List

The Apocalyptic Book List Presented by: The Post Apocalyptic Forge Compiled by: Paul Williams ([email protected]) As with other lists compiled by me, this list contains material that is not strictly apocalyptic or post apocalyptic, but that may contain elements that have that fresh roasted apocalyptic feel. Because I have not read every single title here and have relied on other peoples input, you may on occasion find a title that is not appropriate for the intended genre....please do let me know and I will remove it, just as if you find a title that needs to be added...that is appreciated as well. At the end of the main book list you will find lists for select series of books. Title Author 8.4 Peter Hernon 905 Tom Pane 2011, The Evacuation of Planet Earth G. Cope Schellhorn 2084: The Year of the Liberal David L. Hale 3000 Ad : A New Beginning Jon Fleetwood '48 James Herbert Abyss, The Jere Cunningham Acts of God James BeauSeigneur Adulthood Rites Octavia Butler Adulthood Rites, Vol. 2 Octavia E. Butler Aestival Tide Elizabeth Hand Afrikorps Bill Dolan After Doomsday Poul Anderson After the Blue Russel C. Like After the Bomb Gloria D. Miklowitz After the Dark Max Allan Collins After the Flames Elizabeth Mitchell After the Flood P. C. Jersild After the Plague Jean Ure After the Rain John Bowen After the Zap Michael Armstrong After Things Fell Apart Ron Goulart After Worlds Collide Edwin Balmer, Philip Wylie Aftermath Charles Sheffield Aftermath K. A. Applegate Aftermath John Russell Fearn Aftermath LeVar Burton Aftermath, The Samuel Florman Aftershock Charles Scarborough Afterwar Janet Morris Against a Dark Background Iain M. -

No Truce with Kings” Karen Anderson on Poul Anderson’S Hall of Fame Award

Liberty, Art, & Culture Vol. 29, No. 1 Fall 2010 Inspiration for Poul Anderson’s “No Truce with Kings” Karen Anderson on Poul Anderson’s Hall of Fame Award I wish to thank the members of the Libertarian Future loses itself in a desert sink. We knew the farmland and pastures Society for honoring Poul’s work yet again. He particularly of the Central Valley, watered in those days only by the San valued these awards; the three plaques for stories, and that Joaquin river that meets the Sacramento in the great inland for the Lifetime Achievement Award, were displayed above delta, and the cave-riddled Pinnacles under Fremont Peak in the desk where he worked. the center of the state. I made several false starts on this acceptance, but finally We’d seen missions, presidios, and barracks from San Diego concluded it would be best just to tell you a little about the de Alcalá up the Camino Real by San Juan Bautista and San man who wrote it—where he lived, what he’d done lately, Francisco de Asís, to San Francisco Solano in Sonoma, north what he did on his vacations. of the Bay; and further north on the coast we’d visited the Poul was a fan before he was a pro, and we met at the Russian fort with its Orthodox church; Spain and Russia both 1952 Worldcon. He’d been born in Pennsylvania, spent his wanted San Francisco Bay, even before the gold was found in boyhood in Texas, and after periods in Denmark and outside 1849. -

Sf Commentary 76

SF COMMENTARY 76 30TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION October 2000 THE UNRELENTING GAZE GEORGE TURNER’S NON-FICTION: A SELECTION SF COMMENTARY No. 76 THIRTIETH ANNIVERSARY EDITION OCTOBER 2000 THE UNRELENTING GAZE GEORGE TURNER’S NON-FICTION: A SELECTION COVER GRAPHICS Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Introductions 3 GEORGE TURNER: THE UNRELENTING GAZE Bruce Gillespie 4 GEORGE TURNER: CRITIC AND NOVELIST John Foyster 6 NOT TAKING IT ALL TOO SERIOUSLY: THE PROFESSION OF SCIENCE FICTION No. 27 12 SOME UNRECEIVED WISDOM Famous First Words 16 THE DOUBLE STANDARD: THE SHORT LOOK, AND THE LONG HARD LOOK 20 ON WRITING ABOUT SCIENCE FICTION 25 The Reviews 31 GOLDEN AGE, PAPER AGE or, WHERE DID ALL THE CLASSICS GO? 34 JOHN W. CAMPBELL: WRITER, EDITOR, LEGEND 38 BACK TO THE CACTUS: THE CURRENT SCENE, 1970 George and Australian Science Fiction 45 SCIENCE FICTION IN AUSTRALIA: A SURVEY 1892–1980 George’s Favourite SF Writers URSULA K. LE GUIN: 56 PARADIGM AND PATTERN: FORM AND MEANING IN ‘THE DISPOSSESSED’ 64 FROM PARIS TO ANARRES: ‘The Wind’s Twelve Quarters’ THOMAS M. DISCH: 67 TOMORROW IS STILL WITH US: ‘334’ 70 THE BEST SHORT STORIES OF THOMAS M. DISCH GENE WOLFE: 71 TRAPS: ‘The Fifth Head of Cerberus’ 73 THE REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PRESENT: ‘Peace’ George Disagrees . 76 FREDERIK POHL AS A CREATOR OF FUTURE SOCIETIES 85 PHILIP K. DICK: BRILLIANCE, SLAPDASH AND SLIPSHOD: ‘Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said’ 89 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR: ‘New Dimensions I’ 93 PLUMBERS OF THE COSMOS: THE AUSSIECON DEBATE Peter Nicholls and George Turner George and the Community of Writers 100 A MURMURATION OF STARLING OR AN EXALTATION OF LARK?: 1977 Monash Writers’ Workshop Illustrations by Chris Johnston 107 GLIMPSES OF THE GREAT: SEACON (WORLD CONVENTION, BRIGHTON) AND GLASGOW, 1979 George Tells A Bit About Himself 111 HOME SWEET HOME: HOW I MET MELBA 114 JUDITH BUCKRICH IN CONVERSATION WITH GEORGE TURNER: The Last Interview 2 SF COMMENTARY, No. -

By Poul Anderson Change Without Notice Before, During, Or After the Convention

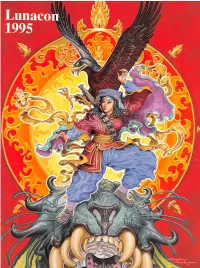

NEW EMPIRES Expansion Set!!! i. Four All New Empires! .A 0 Entity (ultra rare) cards found only in the first print run! r Basic Deck C - CGE1120450 nonrandom cards) $6.95 ea. 127display Expansion Packs - CGE5110 (12 random cards) $2.45 ea. 36/Display ! GALACTIC EMPIRES™ Primary Edition: The 430 card major release! First print run going, going... will beholding Fantastic Graphics and illustrations! s half hour demonstrations games of Eight different empires! Plus 9 Entity (ultra rare) cards found only in the first print run! Galactic Empires in the gaming section. The Basic Deck A & B - CGE1110 (55 cards, 50 nonrandom) demonstrations of Galactic Empires will be $8.95ea. 12/display hosted by designers C. Henry Schulte and Expansion Packs - CGE4110 (12 random) $2.45 ea. 36/Display Richard J. Rausch. Every person who partici Limited Edition Prints (500 signed & numbered) Coming Soon! pates in the demonstration games will receive CLP0001 - ‘Assault on a Clydon Bridge’ (this illustration 20x24) $39.95 Illustration © 1995 Douglas Chaffee. an ultra-rare ‘entity’ card. Call Companion Games for Details: 1-800-49-GAMES or 607-652-9038 The New York Science Fiction Society — The Lunarians, Inc. presents: Lunacon 1995 March 17 - 19 Rye Town Hilton Rye Brook, New York Writer Guest of Honor Poul Anderson Artist Guest of Honor Stephen F. Hickman Fan Guest of Honor: Mike Glyer Featured Filker: Graham Leathers I TOR SALUTES LUNACON GUEST OF HONOR POUL ANDERSON the Hugo and Nebula-award winning SF Grand Master! Don’t miss THE STARS ARE ALSO FIRE, Poul Anderson’s -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 10-1-1996 SFRA ewN sletter 225 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 225 " (1996). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 164. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/164 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (i j ,'s' Review= Issue #225, September/October 1996 IN THIS ISSUE: SFRA INTERNAL AFFAIRS: Proposed SFRA Logo.......................................................... 5 President's Message (Sanders) ......................................... 5 Officer Elections/Candidate Statements ......................... 6 Membership Directory Updates ..................................... 10 SFRA Members & Friends ............................................... 10 Letters (Le Guin, Brigg) ................................................... 11 Editorial (Sisson) ............................................................. 13 NEWS AND INFORMATION ......................................... -

Poul Anderson

TOR FANTASY MARCH 2015 FANTASY SUPER LEAD Brandon Sanderson Words of Radiance The #1 New York Times bestselling sequel to The Way of Kings Brandon Sanderson's epic The Stormlight Archive continues with his #1 New York Times bestselling Words of Radiance. Six years ago, the Assassin in White killed the Alethi king, and now he's murdering rulers all over Roshar; among his prime targets is Highprince Dalinar. Kaladin is in command of the royal bodyguards, a controversial post for his low status, and must protect the king and Dalinar, while secretly mastering remarkable new powers linked to his honorspren, Syl. Shallan bears the ONSALE burden of preventing the return of the Voidbringers and the DATE: 3/3/2015 civilizationending Desolation that follows. The Shattered Plains ISBN13: 9780765365286 hold the answer, where the Parshendi are convinced by their war EBOOK ISBN: 9781429949620 leader to risk everything on a desperate gamble with the very supernatural forces they once fled. PRICE: $9.99 / $11.99 CAN. PAGES: 1328 SPINE: 1.969 IN KEY SELLING POINTS: CTN COUNT: 24 CPDA/CAT: 32/FANTASY • Words of Radiance debuted at #1 on the New York Times SETTING: A FANTASY WORLD bestsellers list in hardcover and continued selling strongly. It also ORIGIN: TOR HC (3/14, 9780 hit the top lists for Publishers Weekly, the Los Angeles Times, 765326362) USA Today, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal. AUTHOR HOME: UTAH • This novel also hit the bestseller lists for Sunday Times of London, NPR, San Francisco Chronicle, Houston Chronicle, Vancouver Sun, National Indie Bestseller List, and Midwest Heartland Indie List. -

Fifty Works of Fiction Libertarians Should Read

Liberty, Art, & Culture Vol. 30, No. 3 Spring 2012 Fifty works of fiction libertarians should read By Anders Monsen Everybody compiles lists. These usually are of the “top 10” Poul Anderson — The Star Fox (1965) kind. I started compiling a personal list of individualist titles in An oft-forgot book by the prolific and libertarian-minded the early 1990s. When author China Miéville published one Poul Anderson, a recipient of multiple awards from the Lib- entitled “Fifty Fantasy & Science Fiction Works That Social- ertarian Futurist Society. This space adventure deals with war ists Should Read” in 2001, I started the following list along and appeasement. the same lines, but a different focus. Miéville and I have in common some titles and authors, but our reasons for picking Margaret Atwood—The Handmaid’s Tale (1986) these books probably differ greatly. A dystopian tale of women being oppressed by men, while Some rules guiding me while compiling this list included: being aided by other women. This book is similar to Sinclair 1) no multiple books by the same writer; 2) the winners of the Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here or Robert Heinlein’s story “If This Prometheus Award do not automatically qualify; and, 3) there Goes On—,” about the rise of a religious-type theocracy in is no limit in terms of publication date. Not all of the listed America. works are true sf. The first qualification was the hardest, and I worked around this by mentioning other notable books in the Alfred Bester—The Stars My Destination (1956) brief notes. -

Fantasy & Science Fiction V024n06

Science Fiction U N E NO TRUCE WITH KINGS a new short novel by POUL ANDERSON RICHARD MATHESON VANCE AANDAHL JACK VANCE / I L • ,vi y V.. r i / J. m Including Venture Science Fiction No Truce With Kings {short novel) POUL ANDERSON 5 Books AVRAM DAVIDSON 59 Pushover Planet CON PEDERSON 65 H. KERR 70 Starlesque {verse) > WALTER Green Magic JACK VANCE 71 Science: The Light That Failed! ISAAC ASIMOV 84 The Weremartini VANCE AANDAHL 95 Ferdinand Feghoot: LXIII GRENDEL BRIARTON 102 Bokko-chan shin’ichi HOSHI 103 Tis The Season To Be Jelly RICHARD MATHESON 107 Another Rib JOHN J. WELLS and MARION ZIMMER BRADLEY 111 There Are No More Good Stories About Mars . {verse) BRIAN W. ALDISS 127 In this issue , , . Coming next month 4 F&SF Marketplace 128 Index to Volume XXIV 130 Cover by Emsh {illustrating "No Truce With Kings”) Joseph W. Ferman; publisher Avram Davidson, executive editor Isaac Asimov, science editor E' ’ LtMkrman, managing editor Yo f> The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, V oiutne 44. No. 6,^ Whole No. 145, June 1963. Published monthly by Mercury Press, Inc., at 404 a copy. Annual subscription $4.50 in U. S. and Possessions, $5.00 in Canada and the Pan American Union; $5.50 in all other countries. Publication office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N. H. EditoHal and general mail should be sent to 347 East 53rd St,, New York 22; N. Y. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N. H. Printed in U. S. A. © 1963 by Mencury Press, Inc. AH rights, including translations into other languages, reserved. -

Five for Frightening Inside Prometheus: Prometheus Award the Keep: the Graphic Novel by F

Liberty and Culture Vol. 25, No. 1 Fall 2006 Five for frightening Inside Prometheus: Prometheus Award The Keep: The Graphic Novel By F. Paul Wilson, Art by Matthew Smith winners’ remarks; IDW, 2005/2006, Issues 1-5, $3.99 ea; WorldCon Report; Trade paperback $19.99 Reviews of fiction by Reviewed by Anders Monsen Gary Bennett, Keith Brooke, David Louis Edelman, The fourth incarnation of F. Paul Wilson’s 1980 horror Naomi Novik, novel, The Keep, appeared in five comic book format in- Ian MacDonald, stallments before being bound into trade paperback edition Chris Roberson; in August, 2006. Counting the novel, the other two ways you David Lloyd’s Kickback; can experience the story is through a feature film (VHS) and Movie review: a board game, although Wilson himself has disparaged the V for Vendetta film version of his novel, and labored for years to bring a new and truer version to the screen. What happens when Wilson writes his own visual script and finds an artist capable and willing to remain loyal to novel, yet also felt deliberately over-stylized. With The Keep: the story? First, to reduce a 332-page novel packed with The Graphic Novel, the roles are almost reversed; the stark ideas about power and mankind’s self-inflicted horrors sketches illuminate the pain of the characters (especially mixed with alien designs upon humanity into 110 pages Glaeken and Magda’s father), and the depth of Rasalom’s of sketches and brief dialog requires some sacrifices. A evil to a much greater degree than the novel. -

Poul Anderson – Hrolf Kraki’S Saga

2012 ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE PAG. 37–48 PHILOLOGICA 1 / GERMANISTICA PRAGENSIA XXI SCANDINAVIAN HEROIC LEGEND AND FANTASY FICTION: POUL ANDERSON – HROLF KRAKI’S SAGA TEREZA LANSING ABSTRACT Hrolf Kraki’s Saga (1974), an American fantasy fiction novel, represents the reception of medieval Scandinavian literature in popular culture, which has played a rather significant role since the 1970s. Poul Anderson treats the medieval sources pertaining to the Danish legendary king with excep- tional fidelity and reconstructs the historical settings with almost scholarly care, creating a world more pagan than in his main source, the Icelandic Hrólfs saga kraka. Written at the height of the Cold War, Anderson’s Iron Age dystopia is a praise of stability and order in the midst of a civilisation under perpetual threat. Keywords medieval Scandinavian literature, Hrólfs saga kraka, literary reception, medievalism, fantasy fiction, Poul Anderson In recent years medieval Scandinavian scholarship is becoming increasingly occupied with the transmission and reception of medieval sources in post-medieval times, look- ing into the ways these sources were interpreted and represented in new contexts, be it scholarly reception, high or popular culture.1 Poul Anderson (1926–2001), an American writer with an education in physics, is mainly known as an author of science fiction, but perhaps because of his Danish extraction, Nordic legend and mythology also captured his attention, and Anderson wrote several novels based on Nordic matter. Anderson was a prolific author; he published over a hundred titles and won numerous awards. Hrolf Kraki’s Saga was published in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series in 1973. It represents a reconstruction of the legend of Hrólfur Kraki, enriched with a great deal of realistic detail adjusted to the taste of the contemporary reader. -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 6-1-1994 SFRA ewN sletter 211 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 211 " (1994). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 151. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/151 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SFRA Revle.... 1211, May/JuDe 1994 BFRAREVIEW laauI #211, may/Junl 1BBit In THII IIIUE: IFRI ImRnll IFFIIRI: President's Message (Mead) New Members & Changes of Address 1993 SFRA Conference Tentative Schedule (HuWFriend) Editorial (Mallett) BEnERIl miICEWny: Forthcoming Books (Mallett) News & Information (Mallett. etc.) FERTUREI: Feature Article: "'The Sense of Wonder' is 'A Sense Sublime'" (Robu) Feature Review: Coover. Robert. Pinocchio in Venice. (Chapman) "Subject Headings for Genre Fiction" (Klossner) REVIEW I: nl.f1ctJll: Anon. The Disney Poster: The Animated Film Oassics !Tom Mickey Mouse to Aladdin. (Klossner) Hershenson. Bruce. Cartoon Movie Posters. (Klossner) Levy. Michael. Natalie Babbitt. (Heller) FlctJll: Allen. Roger McBride & Eric Kotani. Supernova. (Stevens) Anderson, Dana. Charles de Lint & Ray Garton. Cafe Pw-gatorium. (Tryforos) Anderson, Poul. The Time Patrol. (Dudley) Anthony. Piers. Question Quest. (Riggs) AttanaSIo. A. A. Hunting the Ghost Dancer. (Bogstad) Banks. lain M. The State ofthe Art. -

NESFA Press Sampler BOSKONE 58

BOSKONE 58 NESFA Press Sampler This sampler contains a story from four of our most popular books. All these books are available as ebooks and the first three are available as hardcovers. Visit www.nesfapress.org The Effectives All the Lies That Are His Life Call Me Joe Bluebeard’s Wife Believing The Other Stories of Zenna Henderson by ZENNA HENDERSON EPUB: nesfa.org/book/believing-2/ MOBI: nesfa.org/book/believing-3/ Hardcover: nesfa.org/book/believing/ Story Selected: The Effectives Zenna Henderson is best known for her stories of The People, published in The Maga- zine of Fantasy and Science Fiction from the early 1950s to the mid-1970s. The People, a group of human-appearing aliens, escaped the destruction of their home world only to be shipwrecked on Earth, where they struggled to hide their extra abilities. During the same period, Henderson published an equal number of non-People stories. Like the stories of The People, they range from comforting to unnerving. Fans of The People will recognize the same underlying belief in the goodness of people and other beings as they struggle for a chance at a better future. Zenna Henderson Zenna Chlarson Henderson (1917–1983) was born in Tucson, Arizona. Although she became a teacher because the nearest state school was a teacher’s college, Hender- son later stated she’d rather earn her living teaching first grade than any other way. She would make time to write before school and at the end of the day. All her writing exhibits a warmth, gentleness and a sense of the worth of human and non-human beings.