Herbert Marcuse and the Politics of Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Paper to Be Presented at the 6Th European CHEIRON Meeting in Brighton^England, 2-6 September 1987. Research Was Funded

Propriety of the Erich Fromm Document Center. For personal use only. Citation or publication of material prohibited without express written permission of the copyright holder. Eigentum des Erich Fromm Dokumentationszentrums. Nutzung nur für persönliche Zwecke. Veröffentlichungen – auch von Teilen – bedürfen der schriftlichen Erlaubnis des Rechteinhabers. "INSTINCTS" AND THE "FORCES OF PRODUCTION": The Freud-Marx Debates in Eastern and Central Europe* Dr. Ferenc Eros Institute of Psychology, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest In his essay "Psychology and Art Today", the British-American poet Wystan Hugh Auden writes: Both Freud and Marx start from the failures of civiliza tion, one from the poof, one from the ill. Both see human behavior determined, not consciously, but by instinctive needs, hunger and love. Both desire a world where rational choice and self-determination are possible. The difference between them is the inev itable difference between the man who studies crowds in the street, and the man who sees the patient... in the consulting room- Marx sees the direction of the relations between the outer and inner world from without inwards. Freud vice-versa.... The socialist accuses the psychologist of caving in to the status quo, trying to adapt the neurotic to the system, thus depriving him of a potential revolutionary; the psychologist retorts that the socialist is trying to lift himself by his own boot tags, that he fails to understand himself or the fact that lust for money is only one form of the lust for power; and so that after he has won his power by revolution he will recreate the same conditions. -

Critical Theory of Herbert Marcuse: an Inquiry Into the Possibility of Human Happiness

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1986 Critical theory of Herbert Marcuse: An inquiry into the possibility of human happiness Michael W. Dahlem The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dahlem, Michael W., "Critical theory of Herbert Marcuse: An inquiry into the possibility of human happiness" (1986). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5620. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5620 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 This is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s is t s, Any further reprinting of its contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR, Mansfield Library U n iv e rs ity o f Montana Date :_____1. 9 g jS.__ THE CRITICAL THEORY OF HERBERT MARCUSE: AN INQUIRY INTO THE POSSIBILITY OF HUMAN HAPPINESS By Michael W. Dahlem B.A. Iowa State University, 1975 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1986 Approved by Chairman, Board of Examiners Date UMI Number: EP41084 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

This Body, This Civilization, This Repression: an Inquiry Into Freud and Marcuse

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2008 This body, this civilization, this repression: An inquiry into Freud and Marcuse Jeff Renaud University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Renaud, Jeff, "This body, this civilization, this repression: An inquiry into Freud and Marcuse" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 8272. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/8272 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THIS BODY, THIS CIVILIZATION, THIS REPRESSION: AN INQUIRY INTO FREUD AND MARCUSE by JeffRenaud A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through Philosophy in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements -

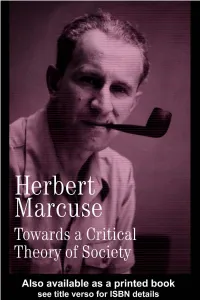

Towards a Critical Theory of Society Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse Edited by Douglas Kellner

TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE EDITED BY DOUGLAS KELLNER Volume One TECHNOLOGY, WAR AND FASCISM Volume Two TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY Volume Three FOUNDATIONS OF THE NEW LEFT Volume Four ART AND LIBERATION Volume Five PHILOSOPHY, PSYCHOANALYSIS AND EMANCIPATION Volume Six MARXISM, REVOLUTION AND UTOPIA TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY HERBERT MARCUSE COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE Volume Two Edited by Douglas Kellner London and New York First published 2001 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 2001 Peter Marcuse Selection and Editorial Matter © 2001 Douglas Kellner Afterword © Jürgen Habermas All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Marcuse, Herbert, 1898– Towards a critical theory of society / Herbert Marcuse; edited by Douglas Kellner. p. cm. – (Collected papers of Herbert Marcuse; v. 2) Includes bibliographical -

Marcuse and Adorno: Objectivity, Mediation, And

Lucas S. Williams Method of Psychoanalysis in the Social University of Chicago José Colen Context of Modern Civilization Universidade de Minho Frankfurt School Adorno and Horkheimer Marcuse Freud 44 Gaudium Sciendi, Nº 5, Dezembro 2013 Lucas S. Williams Method of Psychoanalysis in the Social University of Chicago José Colen Context of Modern Civilization Universidade de Minho 12 1. The problem of human repression under the economic organization, and how to account for it hrough his revolutionary theories, Sigmund Freud pioneered the exploration of the reality of unconscious instinctual drives that constitute the essence of the individual's T personality and therefore of his behavior. Freud, of course, was not unaware of the relation between men's passions and desires, conscious and unconscious, and the social context, that he approached, e.g., in his 1930 book Civilization and its Discontents (Freud, 2005)3, but the effects of the socio-economic framework on human life were never developed by him. Basing himself primarily on Freud's theoretical conception, in Eros and Civilization, Herbert Marcuse attempts to both expose the existence and illustrate the workings of a [capitalist] civilization whose progress has been plagued by domination and 'surplus-repression' - and thus explores the bondage of the individual in terms of Freud's analysis of the human psyche. 1 J. A. Colen is Ph. D. in Political Sciences, Researcher associated to the Centro de Estudos Humanísticos from Universidade do Minho (Braga). He is also Researcher at CESPRA - Centre d'études sociologiques et politiques Raymond-Aron from the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (Paris) and Visiting Scholar at Notre Dame University (Indiana) for 2014. -

Norman O. Brown, 1913–2002

OBITUARY Norman O. Brown, 1913–2002 orman O. Brown was born in New Mexico in 1913 and educated at Balliol College, Oxford, and at the University of Wisconsin. His tutor at Oxford was NIsaiah Berlin. A product of the 1930s, Brown was active in left-wing politics – for example, in the 1948 Henry Wallace presidential campaign – and his work belongs within the history of Marxist, as well as psychoanalytic, thought. During World War II, he worked in the Office of Strategic Services, where his supervisor was Carl Schorske and his colleagues included Herbert Marcuse and Franz Neumann. Marcuse urged Brown to read Freud, leading, in 1959, to Brownʼs most memorable work, Life Against Death. Brown taught Classics at Wesleyan University and was a member of the History of Consciousness Department at the University of California at Santa Cruz. Although Life Against Death made him an icon of the New Left, he successfully eschewed publicity, insisting to the end on his primary identity as teacher. There is still no better introduction to Life Against Death than the one that Brown wrote in 1959. The book was inspired, he explained, by a felt ʻneed to reappraise the nature and destiny of manʼ. The ʻdeep study of Freudʼ was the natural means for this undertaking. His motives, Brown continued, were political in the most profound sense of the term: ʻInheriting from the Protestant tradition a conscience which insisted that intellectual work should be directed toward the relief of manʼs estate, I, like many of my generation, lived through the superannuation of the political categories which informed liberal thought and action in the 1930s.ʼ ʻThose of us who are tempera- mentally incapable of embracing the politics of sin, cynicism and despairʼ, he added, were ʻcompelled to re-examine the classic assumptions about the nature of politics and about the political character of human nature.ʼ How did it come about, at the dawn of the 1960s, that Freud appeared as the suc- cessor to a ʻsuperannuatedʼ, but not yet surpassed, Marxist project? Life Against Death addressed this question. -

Marcuse's Eros and Civilization

r- EROS AND CIVILIZATION A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud HERBERT MARCUSE With a N_ew Preface by the Author BEACON PRESS BOSTON Copyright 1955, © 1966 by The Beacon Press Library of Congress catalog card number: 66-3219 WRITTEN IN MEMORY OF International Standard Book Numbers: 0-8070-1554-7 SOPHIE MARCUSE 0-8070-15 55-5 (pbk.) First published as a Beacon Paperback in 1974 1901-1951 Beacon Press books are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 Contents PoLmcAL PREFACE 1966 xi PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION xxvii INTRODUCTION 3 PAu I: UNDER THE RULE OF THE REALITY PRINCIPLE 1. The Hidden Trend in Psychoanalysis 11 Pleasure principle and reality principle Genetic and individual repression " Return of the repressed " in civilization Civilization and want: rationalization of renunciation "Remembrance of things past" as vehicle of libera- tion 2. The Origin of the Repressed Individual (Onto- genesis) · 21 The mental apparatus as a dynamic union of opposites Stages in Freud's theory of instincts Common conservative nature of primary instincts Possible supremacy of Nirvana principle Id, ego, superego "Corporealization" of the psyche Reactionary character of superego Evaluation of Freud's basic conception Analysis of the interpretation of history in Freud's psy- chology Distinction between repression and " surplus-repres- • I viii CONTENTS CONTENTS 1X Alienated labor and the performance principle PART II: BEYOND THE REALITY PRINCIPLE Organization -

Psychoanalysis and the Methodology of Critique Amy Allen Department of Philosophy Penn State University Forthcoming in Constellations, June 2016

Psychoanalysis and the Methodology of Critique Amy Allen Department of Philosophy Penn State University Forthcoming in Constellations, June 2016 In his introduction to Eros and Civilization, Herbert Marcuse distinguishes his philosophy of psychoanalysis from psychoanalytic therapy by explaining that the former aims “not at curing individual sickness, but at diagnosing the general disorder.”1 With this claim, Marcuse expresses a thought that has run through first, second, and third generation critical theory, in different ways, namely, that the methodology of critical theory can be understood as somehow analogous to psychoanalytic technique. This analogy holds that the critical theorist stands in relation to the pathological social order as the analyst stands in relation to the analysand, and that the aim of critical theory is to effect the diagnosis and, ultimately, the cure of social disorders or pathologies. This idea was famously developed in careful detail in Jürgen Habermas’s early work, Knowledge and Human Interests.2 There, Habermas defined psychoanalysis as a science of “methodical self-reflection” (KHI, 214), that is, as a form of depth hermeneutics that aims to analyze those aspects of the self that have been alienated from the self and yet remain a part of it. In other words, it aims to analyze what Freud once referred to as the “internal foreign territory” of the unconscious.3 In KHI, Habermas understood the individual psyche in communicative terms; hence, for him, unconscious wishes are those that have been “exclude[d]from public communication,” or “delinguisticized” (KHI, 224), but that continue to disrupt the subject’s communication with him or herself in the form of dreams, slips of the tongue, and other interruptions (KHI, 227). -

Front Matter by Editor, in Eros and Civilization: Philosophical Inquiry Into Freud

Front Matter by Editor, in Eros and Civilization: Philosophical Inquiry Into Freud. by Herbert Marcuse. (Beacon Press, Boston, MA, 1955). pp. iii-8. [Bibliographic Details][View Documents ] -- [iii] -- Front Matter [Title Page and Credits] EROS AND CIVILIZATION A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud HERBERT MARCUSE With a New Preface by the Author BEACON PRESS BOSTON -- [iv] -- Copyright 1955, © 1966 by The Beacon Press Library of Congress catalog card number: 66-3219 International Standard Book Numbers : 0-8070-1554-7 0-8070-1555-5 (pbk .) First published as a Beacon Paperback in 1974 Beacon Press books are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 109876543 -- [v] -- WRITTEN IN MEMORY OF SOPHIE MARCUSE 1901-1951 -- [vi] -- -- [vii] -- Contents POLITICAL PREFACE 1966 xi PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION xxvii INTRODUCTION 3 PART I: UNDER THE RULE OF THE REALITY PRINCIPLE 1. The Hidden Trend in Psychoanalysis 11 Pleasure principle and reality principle Genetic and individual repression "Return of the repressed" in civilization Civilization and want: rationalization of renunciation "Remembrance of things past" as vehicle of liberation 2.The Origin of the Repressed Individual (Ontogenesis) 21 The mental apparatus as a dynamic union of opposites Stages in Freud's theory of instincts Common conservative nature of primary instincts Possible supremacy of Nirvana principle Id, ego, superego "Corporealization" of the psyche Reactionary character of superego Evaluation of Freud's basic conception Analysis of the interpretation of history in Freud's psychology Distinction between repression and "surplus-repression" Alienated labor and the performance principle Organization of sexuality: taboos on pleasure Organization of destruction instincts Fatal dialectic of civilization -- viii -- 3. -

The Reception of Critical Theory in the Former Yugoslavia

Praxis Philosophy’s ’Older Sister‘ The Reception of Critical Theory in the Former Yugoslavia Marjan Ivković* Without any doubt, the former Yugoslavia was among the more fertile soils globally for the reception and flourishing of the tradition of Critical Theory over a span of several decades. Practically all major works by both the ‘first’- and ‘second-generation’ critical theorists were translated into Serbo-Croatian in the 1970s and 1980s. Not only were there translations of the most influential studies of Critical Theory’s history and theoretical legacy of that time (Martin Jay, Alfred Schmidt and Gian-Enrico Rusconi), there were also studies by local authors such as Simo Elaković’s Filozofija kao kritika društva (Philosophy as Critique of Society) and Žarko Puhovski’s Um i društvenost (Reason and Sociality). Contemporary Serbian political scientist Đorđe Pavićević remarks about Critical Theory in Yugoslavia that “this group of authors can perhaps be considered the most thoroughly covered area of scholarhip within political theory and philosophy in terms of both translations and original works up to the early 1990s” (2011: 51). Yet, throughout socialist times, the broad and differentiated reception of Critical Theory never really crossed the threshold of a truly original appropriation, whether it be attempts to elaborate existing perspectives in Critical Theory, modify them in light of particular socio-historical circumstances of the local context, or apply them as a research framework for the empirical study of society. The peculiarity -

Renaissance of Herbert Marcuse: a Study on Present Interest in Marcuse’S Interdisciplinary Critical Theory*

Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems 17(3-B), 659-683, 2019 RENAISSANCE OF HERBERT MARCUSE: A STUDY ON PRESENT INTEREST IN MARCUSE’S INTERDISCIPLINARY CRITICAL THEORY* Maroje Višić** Dubrovnik, Croatia DOI: 10.7906/indecs.17.3.19 Received: 17 August 2019. Regular article Accepted: 26 September 2019. ABSTRACT Recent years have witnessed a revival of interest in Marcuse’s critical theory. This can be partly ascribed to Marcuse’s interdisciplinary approach to humanities and social sciences. Many of Marcuse’s ideas and concepts are tacitly present in contemporary social and ecological movements. Contemporary literature on Marcuse is positively inclined to his theory while the critique of Marcuse dates back to the ‘70s, and remains largely unimpaired. This fact poses significant challenges to the revival of Marcuse’s critical theory. This study sets out to report on current interest in Marcuse’s critical theory trying to correct “past injustices” by responding to negative criticism. The main flaw of such criticism – as we see it – is in failing to perceive interdisciplinary character of Marcuse’s critical theory. Marcuse’s renaissance cannot be complete without, to use dialectical term, sublating the history of negative criticism. KEY WORDS Marcuse, interdisciplinary critical theory, Frankfurt School, social movements, critique CLASSIFICATION JEL: B24 *Parts of this article were presented and discussed at the international course Theatrum Mundi X: *Progress & Decadence, Dubrovnik, 2019. Some of the arguments in this article were published in my *book Kritika i otpor: osnovne crte kritičke filozofije Herberta Marcusea, Naklada Breza, Zagreb, 2017. **Corresponding author, : [email protected]; -; **Tina Ujevića 7, HR – 20 000 Dubrovnik, Croatia * M. -

Negations Essays in Critical Theory

Negations Essays in Critical Theory Herbert Marcuse may fly Negations Herbert Marcuse Herbert Marcuse’s Negations is both a radical critique of capitalist modernity and a model of materialist dialectical thinking. In a series of essays, originally written in the period stretching from the 1930s to 1960s, Marcuse takes up the presupposed categories that have, and continue to, ground thought and action in our administered society: liberalism, industrialism, individualism, hedonism, aggres- sion. This book is both a testament to a great thinker and a still vital strand of thought in the comprehension and critique of the mod- ern organized world. It is essential reading for younger scholars and a radical reminder for those steeped in the tradition of a critical theory of society. With a brilliance of conception combined with an insistence on the material conditions of thought and action, this book speaks both to the particular contents engaged and to the fundamental grounds of any critique of organized modernity. may fly www.mayfl ybooks.org Today, at one and the same time, scholarly publishing is drawn in two directions. On the one hand, this is a time of the most exciting theoretical, political and artistic projects that respond to and seek to move beyond global administered society. On the other hand, the publishing industries are vying for total control of the ever-lucrative arena of scholarly publication, creating a situation in which the means of distribution of books grounded in research and in radical interrogation of the present are increasingly restricted. In this context, MayFlyBooks has been established as an independent publishing house, publishing political, theoretical and aesthetic works on the question of organization.