2.0 the Shaping of the Salisbury District Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAUID Exchange Name FTTC/P Available County Or Unitary Authority

SAUID Exchange Name FTTC/P Available County or Unitary Authority EMABRIP ABBOTS RIPTON FTTC/P Now Huntingdonshire District SWABT ABERCYNON FTTC/P Now Rhondda, Cynon, Taf - Rhondda, Cynon, Taff SWAA ABERDARE FTTC Now Rhondda, Cynon, Taf - Rhondda, Cynon, Taff NSASH ABERDEEN ASHGROVE FTTC Now Aberdeen City NSBLG ABERDEEN BALGOWNIE FTTC Now Aberdeen City NSBDS ABERDEEN BIELDSIDE FTTC Now Aberdeen City NSCTR ABERDEEN CULTER FTTC Now Aberdeen City NSDEN ABERDEEN DENBURN FTTC Now Aberdeen City NSKNC ABERDEEN KINCORTH FTTC Now Aberdeen City NSKGW ABERDEEN KINGSWELLS FTTC Now Aberdeenshire NSLNG ABERDEEN LOCHNAGAR FTTC Now Aberdeen City NSNTH ABERDEEN NORTH FTTC Now Aberdeen City NSPRT ABERDEEN PORTLETHEN FTTC Now Aberdeenshire NSWES ABERDEEN WEST FTTC Now Aberdeen City WNADV ABERDOVEY FTTC/P Now Gwynedd - Gwynedd SWAG ABERGAVENNY FTTC Now Sir Fynwy - Monmouthshire SWAAZ ABERKENFIG FTTC Now Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr - Bridgend WNASO ABERSOCH FTTC/P Now Gwynedd - Gwynedd SWABD ABERTILLERY FTTC/P Now Blaenau Gwent - Blaenau Gwent WNAE ABERYSTWYTH FTTC/P Now Sir Ceredigion - Ceredigion SMAI ABINGDON FTTC & FoD Now Vale of White Horse District THAG ABINGER FTTC Now Guildford District (B) SSABS ABSON FTTC Now South Gloucestershire LCACC ACCRINGTON FTTC Now Hyndburn District (B) EAACL ACLE FTTC Now Broadland District CMACO ACOCKS GREEN FTTC & FoD Now Birmingham District (B) MYACO ACOMB FTTC & FoD Now York (B) LWACT ACTON FTTC Now Ealing London Boro SMAD ADDERBURY FTTC Now Cherwell District LSADD ADDISCOMBE FTTC Now Croydon London Boro MYADE ADEL FTTC & FoD -

Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs AONB Market Town Growth

Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs AONB Market Town Growth Final Report May 2006 Entec UK Limited Report for Cranborne Chase and Richard Burden Planning and Landscape Officer West Wiltshire Downs AONB Office AONB Castle Street Cranborne Dorset BH21 5PZ Market Town Growth Main Contributors Final Report David Fovargue Robert Deanwood May 2006 Tim Perkins Entec UK Limited Issued by ………………………………………………………… Robert Deanwood Approved by ………………………………………………………… Tim Perkins Entec UK Limited Gables House Kenilworth Road Leamington Spa Warwickshire CV32 6JX England Tel: +44 (0) 1926 439000 Fax: +44 (0) 1926 439010 h:\projects\ea-210\17000-17999\17566 cranborne chase planning research\data\reports\final market town growth report 30 may.doc Certificate No. EMS 69090 Certificate No. FS 13881 In accordance with an environmentally responsible approach, this document is printed on recycled paper produced from 100% post-consumer waste, or on ECF (elemental chlorine free) paper i Contents 1. Future Market Town Growth 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.1.1 Background 1 1.1.2 Structure of the review 1 1.2 Planned Developments 2 1.2.1 Approach 2 1.3 Locations for growth with potential impacts 3 1.4 The potential for future growth 4 1.5 Potential Impacts on the AONB from the emerging Regional Spatial Strategies 5 1.6 Conclusions 7 1.6.1 Existing Local Plan allocations within the AONB 7 1.6.2 Existing Local Plan allocations outside AONB 7 1.6.3 Growth areas within the emerging Regional Spatial Strategy 7 1.7 Recommendations for the Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs AONB Partnership 8 Table 1.1 All allocations for growth within Cranborne Chase AONB 3 Table 1.2 Current and future housing and employment provision 4 Appendix A Land allocations Appendix B Maps Indicating Locations of Planned Growth h:\projects\ea-210\17000-17999\17566 cranborne chase planning research\data\reports\final market town growth report May 2006 30 may.doc © Entec ii h:\projects\ea-210\17000-17999\17566 cranborne chase planning research\data\reports\final market town growth report May 2006 30 may.doc © Entec 1 1. -

2004 No. 3211 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. 3211 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Local Authorities (Categorisation) (England) (No. 2) Order 2004 Made - - - - 6th December 2004 Laid before Parliament 10th December 2004 Coming into force - - 31st December 2004 The First Secretary of State, having received a report from the Audit Commission(a) produced under section 99(1) of the Local Government Act 2003(b), in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by section 99(4) of that Act, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and application 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Local Authorities (Categorisation) (England) (No.2) Order 2004 and shall come into force on 31st December 2004. (2) This Order applies in relation to English local authorities(c). Categorisation report 2. The English local authorities, to which the report of the Audit Commission dated 8th November 2004 relates, are, by this Order, categorised in accordance with their categorisation in that report. Excellent authorities 3. The local authorities listed in Schedule 1 to this Order are categorised as excellent. Good authorities 4. The local authorities listed in Schedule 2 to this Order are categorised as good. Fair authorities 5. The local authorities listed in Schedule 3 to this Order are categorised as fair. (a) For the definition of “the Audit Commission”, see section 99(7) of the Local Government Act 2003. (b) 2003 c.26. The report of the Audit Commission consists of a letter from the Chief Executive of the Audit Commission to the Minister for Local and Regional Government dated 8th November 2004 with the attached list of local authorities categorised by the Audit Commission as of that date. -

Pacman TEMPLATE

Updated May 2020 National Cardiac Arrest Audit Participating Hospitals The total number of hospitals signed up to participate in NCAA is 194. England Birmingham and Black Country Participant Alexandra Hospital Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust Birmingham Heartlands Hospital University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust City Hospital Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust Good Hope Hospital University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust Hereford County Hospital Wye Valley NHS Trust Manor Hospital Walsall Healthcare NHS Trust New Cross Hospital The Royal Wolverhampton Hospitals NHS Trust Russells Hall Hospital The Dudley Group of Hospitals NHS Trust Sandwell General Hospital Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust Solihull Hospital University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust Worcestershire Royal Hospital Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust Central England Participant George Eliot Hospital George Eliot Hospital NHS Trust Glenfield Hospital University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust Kettering General Hospital Kettering General Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Leicester General Hospital University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust Leicester Royal Infirmary University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust Northampton General Hospital Northampton General Hospital NHS Trust Hospital of St Cross, Rugby University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust University Hospital Coventry University Hospitals Coventry -

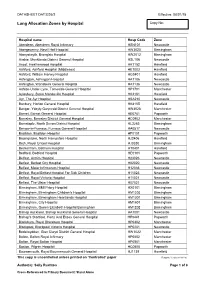

Lung Allocation Zones by Hospital Copy No

DATASHEET DAT3226/2 Effective: 08/01/18 Lung Allocation Zones by Hospital Copy No: Hospital name Hosp Code Zone Aberdeen, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary HSN101 Newcastle Abergavenny, Nevill Hall Hospital HW3020 Birmingham Aberystwyth, Bronglais Hospital HW2012 Birmingham Airdrie, Monklands District General Hospital HSL106 Newcastle Ascot, Heatherwood Hospital HK1152 Harefield Ashford, Ashford Hospital (Middlesex) HE1003 Harefield Ashford, William Harvey Hospital HG0401 Harefield Ashington, Ashington Hospital HA1106 Newcastle Ashington, Wansbeck General Hospital HA1136 Newcastle Ashton-Under-Lyne, Tameside General Hospital HP1701 Manchester Aylesbury, Stoke Mandeville Hospital HK2101 Harefield Ayr, The Ayr Hospital HSA210 Newcastle Banbury, Horton General Hospital HK4105 Harefield Bangor, Ysbyty Gwynedd District General Hospital HW4028 Manchester Barnet, Barnet General Hospital HE0701 Papworth Barnsley, Barnsley District General Hospital HC0902 Manchester Barnstaple, North Devon District Hospital HL3265 Birmingham Barrow-In-Furness, Furness General Hospital HA0517 Newcastle Basildon, Basildon Hospital HF0101 Papworth Basingstoke, North Hampshire Hospital HJ2406 Harefield Bath, Royal United Hospital HJ3330 Birmingham Beckenham, Bethlem Hospital HT0401 Harefield Bedford, Bedford Hospital HE0101 Papworth Belfast, Antrim Hospital H23026 Newcastle Belfast, Belfast City Hospital H02020 Newcastle Belfast, Mater Infirmorum Hospital H12036 Newcastle Belfast, Royal Belfast Hospital For Sick Children H11023 Newcastle Belfast, Royal Victoria Hospital H11021 -

New Specialist Nursing Team for End of Life Care Hospital Above Average

Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust Decembernewslink 2015 Issue 29 New specialist Volunteers needed to act as ward nursing team for companions for dementia patients end of life care Staff are looking for new volunteers who can give up some of their free time to provide companionship to patients with dementia to support them A new specialist nursing service in hospital, as part of a new pilot on Redlynch and Pitton wards. has started that will give additional support to ward nursing While the Trust runs the successful communication and interpersonal and medical teams who provide Engage programme, where volunteers skills, an approachable friendly and increase social interaction for patients caring manner and would be able to end of life care to patients. through quizzes, discussion groups give up around two to three hours and memory games, ward companions a week for a morning or afternoon. While the Hospital Palliative Care Team will act as “friends”, giving additional Interviews and checks would be currently treat patients who have support and company for patients carried out, and training provided for complex physical, psychological and during their hospital stay. successful candidates.“ emotional needs, the new specialist nurses will give extra support to ward Jo Jarvis, Voluntary Services Manager People interested in becoming a ward staff caring for patients who need less said: “Our volunteers find the work companion should contact Jo Jarvis, complex support. and time that they give to our patients Voluntary Services Manager on 01722 interesting and rewarding. We are 336262, extension 4026 for more They will also have a staff education looking for people who have good details. -

The London Gazette, 26Th February 1976 2953

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 26TH FEBRUARY 1976 2953 A copy of the Order and the map contained in it has SELBY DISTRICT COUNCIL been deposited and may be inspected free of charge at NOTICE OF CONFIRMATION OF PUBLIC PATH ORDER the office of the Secretary of Huntingdon District Council, County Buildings, Huntingdon during normal office hours. HIGHWAYS ACT, 1959 Any representation or objection with respect to the COUNTRYSIDE ACT, 1968 Order may be sent in writing to the office of the Secretary, The District Council of Selby (Parish of Lead—Bridlepath Huntingdon District Council, County Buildings, Hunting- No. 1) Public Path Diversion Order No. 2, 1975 don before the 9th April 1976, and should state the grounds upon which it is made. Notice is hereby given that on the 13th February 1976 If no representation or objection are duly made, or if the District Council of Selby confirmed the above-named any so made are withdrawn the Huntingdon District Order. Council may instead of submitting the Order to the Secre- The effect of the Order as confirmed is to divert the tary of State for the Environment themselves confirm the public right of way running from the Crooked Billet and Order. If the Order is submitted to the Secretary of State along the drive way to Leadhall Farmhouse to a line running any representations and objections which have been duly parallel to the existing right of way on the eastern side made and not withdrawn will be transmitted with the of the fence to the grounds of Leadhall Farmhouse. Order. A copy of the Order as confirmed and the map contained in it has been deposited and may be inspected free of Dated 13th February 1976. -

Oranisation List Ex COINS 22 Jan 10

Code Description DCM048 Department for Culture, Media and Sport ACE048 Arts Council of England ACL048 Arts Council of England Lottery AER048 Alcohol Education and Research Council - from 07-08 AER033 BFI048 British Film Institute BRL048 British Library BRM048 British Museum BTA048 Visit Britain CAE048 Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment EHG048 English Heritage FCL048 UK Film Council FLA048 Football Licensing Authority GBG048 Gambling Commission HBL048 Horserace Betting Levy Board HLF048 Heritage Lottery Fund IWM048 Imperial War Museum MCM048 Millennium Commission NES048 National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts - from 07-08 NES063 NGL048 National Gallery NHF048 National Heritage Memorial Fund NHM048 Natural History Museum NLB048 Big Lottery Fund NLC048 National Lottery Commission NLD048 National Lottery Distribution Fund NLL048 National Lottery: UKSC Lottery NMG048 National Museums Liverpool NMM048 National Maritime Museum NMS048 National Museum of Science and Industry NOF048 New Opportunities Fund NPG048 National Portrait Gallery RAM048 Royal Armouries Museum RCM048 Museums, Libraries and Archives Council RPL048 Registrar of the Public Lending Right SEL048 Sport England Lottery SPE048 Sport England TGL048 Tate Gallery UKS048 UK Sport VAM048 Victoria and Albert Museum WCO048 Wallace Collection OLF048 Olympic Lottery Distribution Fund OLD048 Olympic Lottery Distributor OLA048 Olympic Delivery Authority CCT048 Churches Conservation Trust GFF048 Geffrye Museum HMM048 Horniman Museum SJS048 Sir John Soane's -

The Route to Success in End of Life Care

National End of Life Care Programme improving end of life care TheRoutes route to to Success success in endin end of of life life carecare – achieving – achieving quality environments for care at end of life quality environments for care at end of life 1 Contents Introduction and aims of the guide Part 1 1.1 Background 1.2 Enhancing the healing environment 1.3 End of life care strategy 1.4 The Hospice Design competition 1.5 Emerging themes in design for end of life care environments 1.6 Steps to success Part 2 2.1 End of Life Care Pathway 2.2 Provision for relatives 2.3 Delivery of high quality care 2.4 Bereavement services 2.5 Viewing rooms Appendix 1. Useful resources 2. Recommendations on mortuary design 3. List of participating organisations 2 Introduction “The physical environment of different settings, including hospitals and care homes, can have a direct impact on the experience of care for people at the end of life and on the memories of their carers and families.” (End of Life Care Strategy, Department of Health, 2008) There is now a great deal of evidence about the It is important that when new buildings or critical importance to patients, relatives and staff of refurbishments are planned we take the opportunity the environment of care. It not only supports recovery to make changes that will improve service delivery and but is also an indicator of people’s perception of the quality. The aim of the guide is to provide practical quality of care. However, until relatively recently there support to those charged with delivering end of life has been little investment in identifying the aspects care services, showing how patients’ and relatives’ of the environment that are especially important for experience can be improved through relatively small those receiving palliative care, their relatives and the scale environmental changes. -

1. Introduction

1. INTRODUCTION THE WILTSHIRE LANDSCAPE Although Wiltshire is dominated by the vast sweeps of the chalk downs, its landscape is highly varied with intimate river valleys contrasting with open uplands and broad vales. The significance of the landscape of Wiltshire is acknowledged in the designation of 44% of the area administered by Wiltshire County Council as Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). This comprises 38% (1,725km) of the North Wessex Downs AONB, 61% (983km) of the Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs AONB and 6% (2,040km) of the Cotswolds AONB. In addition a small section to the far south east of the county is within the New Forest National Park. Wiltshire is located in the south west of England. To the west are Somerset and Gloucestershire, to the south Dorset, to the south east Hampshire and to the east Berkshire. Within Wiltshire there are 4 district authorities: North Wiltshire, West Wiltshire, Salisbury and Kennet and the unitary authority Swindon Borough Council. Wiltshire covers approximately 3,255 square kilometres and has a population of around 433,000. The population is largely rural with nearly half living in towns or villages of fewer than 5,000 people. A quarter of the county’s inhabitants live in settlements of fewer than 1,000 people. The location and context of the study area are shown in Figure 1. WILTSHIRE LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT The Wiltshire Landscape Character Assessment was commissioned by Wiltshire County Council and undertaken by Land Use Consultants between January 2004 and April 2005. The project was directed by a steering group comprising officers from the County Council and constituent district and unitary authorities. -

2006 No. 3096 LOCAL GOVERNMENT

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2006 No. 3096 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Local Authorities (Categorisation) (England) Order 2006 Made - - - - 17th November 2006 Laid before Parliament 24th November 2006 Coming into force - - 15th December 2006 The Secretary of State, makes the following Order in exercise of the powers conferred by section 99(4) of the Local Government Act 2003(a). In accordance with section 99(4) of that Act she has received a report from the Audit Commission(b) produced under section 99(1) of that Act. Citation, commencement and application 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Local Authorities (Categorisation) (England) Order 2006 and shall come into force on 15th December 2006. (2) This Order applies in relation to English local authorities(c). Categorisation report 2. The English local authorities (“authorities”), to which the report of the Audit Commission dated 31st August 2006 relates, are, by this Order, categorised in accordance with their categorisation in that report. 4 Stars Authorities 3. The authorities listed in Schedule 1 to this Order are categorised as 4 stars. 3 Stars Authorities 4. The authorities listed in Schedule 2 are categorised as 3 stars. 2 Stars Authorities 5. The authorities listed in Schedule 3 are categorised as 2 stars. (a) 2003.c.26. (b) For the definition of “Audit Commission”, see section 99(7) of the Local Government Act 2003. The report of the Audit Commission consists of a letter from the Chief Executive of the Audit Commission to the Minister for Local Government and Community Cohesion dated 31st August 2006 with an attached list of local authorities categorised by the Audit Commission as at that date. -

Spring Auction 2021 Online and by Post

Spring Auction 2021 Online and by Post Some exciting and rarely available fishing opportunities in England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, France, Belgium and Norway. A variety of flies, fishing tackle, shooting, art, literature and experiences. Flies tied by Nigel Nunn – see Lot 43 Auction commences 19 March Postal bids must be received by 24 March Online bids close through the evening of 28 March from 5pm Bid at: www.wildtrout.org/auction For an illustrated catalogue including late lots, please visit: www.wildtrout.org The Wild Trout Trust wishes to thank the donors of lots for their very kind support and generosity Auction We invite you to participate in our 2021 Spring Auction (online and by post). The auction will be hosted on www.wildtrout.org with the lots visible from 19 March and ending sequentially through the evening of 28 March 2021 from 5pm. To search for a specific lot, use the search facility and enter the lot number or search more generally for rivers, rods, reels or guides. The exact closing time of each lot will be next to its description. The highest bidder for each lot at the end of the auction on 28 March 2021 wins that lot. To view the illustrated catalogue, visit the WTT website (www.wildtrout.org) where lot descriptions and photographs can be found, along with an interactive map of all the fishing lots. Bids Bidding on www.wildtrout.org works similarly to leaving ‘commission bids’ at a live auction. You place a bid for the most you are willing to pay for a lot and, if you are the winning bidder, you will pay the amount necessary to beat the next highest bid.