IN NEW JERSEY, 1776-1807 Jan Ellen Lewis*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Co R\). 595 HISTORY of CONGRESS

\0 rtY\Y\o..\s o~ Co r\). 595 HISTORY OF CONGRESS. 596 597 H. OF R. Case 0/ .Tonathan Robbins. MARCH, 1800. ingston, Nathaniel Macon, Peter Muhlenberg, An Platt, John Randolph, Samuel Sewall, John Smilie, but he h thony New, John Nicholas, Joseph H. Nicholson, John John Smith, David Stone, Thomas Sumter, Benjamin not bee'n Randolph, John Smilie, John Smith, Samuel Smith, Taliaferro, George Thatcher, Abram Trigg, John Trigg, sive. FJ Richard Dobbs Spaight, Richard Stanford, David Stone, to shed Philip Van Cortlandt, Joseph B. Varnum, Peleg Wads tIlea~g-u Thomas Sumter, Benjamin Taliaferro, John Thomp. worth, and Robert Williams. son, Abram Trigg, John Trigg, Philip Van Cortlandt, N..l.Ys-Theodorus Bailey, Jonathan Brace, SllIlluel been ass Joseph B. Varnum, and Robert Williams. J. Cabell, Gabriel Christie, William Craik, John Den men of 1 N..l.Ys-George Baer, Bailey Bartlett, James A. Bay nis, George Dent. Joseph Eggleston, Thomas Evans, not thin ard, Jonathan Brace, John Brown, Christopher G. Samuel Goode, William Gordon, Edwin Gray, An voted to Champlin, William Cooper, William Craik, John drew Gregg, William Barry Grove, John A. Hanna, taiued il Davenport, Franklin Davenport, John Dennis, George Archibald Henderson, William H. Hill, James Jones, those a( Dent, Joseph Dickson, William Edmond, Thomas Aaron Kitchell, Matthew I.yon, James Linn, Abra ing to d Evans, Abiel Foster, Dwight Foster, Jonathan Free ham Nott, Harrison G. Otis, Robert Page, Josiah Par in supp maq.,Henry Glen, Cha cey Goodrich, Elizur Goodrich, ker, Thomas Pinckney, Leven Powell, John Reed, order in William Gordon, liam H. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Votes and Proceedings of the General Assembly of the State of New-Jersey

VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTEENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY STATEOF THE O F N E IV-J E R S E T. At a SESSION begun at Trenton on the 28th Day of 05iober 1788, and continued by Adjournments. BEING THE FIRST SITTING. TRENTON: PRINTED BY ISAAC COLLINS. M.DCC.LXXXVIII. LIST of Perfons returned as Members of the LEGISLATIVE-COUNCIL Bergen, Peter Haring, EJex, John Chetwood, Middlefex, Benjamin Manning, Monmouth, Afhcr Holmes-, Ephraim Martin, Jofeph Smith, Jofeph Ellis, £ Efquires. John Mayhew, Jeremiah Eldredge, Robert-Lettis Hooper, V. P. Abraham Kitchel, Samuel Ogden, Mark Thompfon, LIST of Perfons returned as Members of the GENERAL ASSEMBLY. VOTES( J ) AND PROCE EDINGS OF THE THIRTEENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE State of New-Jersey. TRENTON, Tuefday, Otlober 28, 1788. BEING the Time and Place appointed by Law for the firfl Meeting of the General AfTembly, chofen at the annual Election, on the fourteenth In- ftant, the following Perfons returned as Members attended, to wit, Ifaac Nicoll, returned as one of the Members of the County of Bergen ; Henry Garritfe, as the of the County of Eflex Combs, as one of the Mem- one of Members ; John bers of the County of Middlefex ; Thomas Little and James Rogers, as two of the Members of the County of Monmouth ; Edward Bunn, Robert Blair and John Hardenburgh, as Members for the County of Someriet ; Jofeph Biddle, Robert-Strettle' Jones, and Daniel Newbold, as Members from the County of Bxirlington ; Franklin Davenport, as one of the Members of the County of Gloucefter ; Elijah Townfend and Richard Townfend, -

LEGISLATIVE FRANKS of NEW JERSEY by Ed and Jean Siskin

Ed & Jean Siskin ~ LEGISLATIVE FRANKS OF NJ LEGISLATIVE FRANKS OF NEW JERSEY By Ed and Jean Siskin The franking privilege is the right to send and or receive mail free from postage. The word frank comes from the Latin via French and Middle English and means free. Samuel Johnson’s famous dictionary of 1755 defines Frank as “A letter which pays no postage” and To Frank as “To exempt letters from postage.” Currently we use the redundant term “free frank” but this is a modern philatelic invention. The term “free frank” does not appear in any British or American legislation or regulation that we’ve been able to find. Insofar as we can determine, “free frank” is a term which started to be used in the 1920’s by stamp dealers. They had begun the illogical use of “franked” to refer to the stamps on a cover and needed a way to refer to franked stampless covers. The term “free frank” was permanently implanted in our lexicon by Edward Stern in his 1936 book History of “Free Franking” of Mail in the United States. Stern was a major stamp dealer of his day and one of the first serious collectors of franked material. We had an original photograph, Figure 1, of Stern showing his Frank Collection to ex-President Hoover at the 1936 New York International Philatelic Exhibition. Wilson Hulme talked us into donating that photograph to the Smithsonian where it now resides. Stern’s book pictures an incredible collection of rare and desirable franked covers. However, some of the discussion in the book is not as fully researched as we would like and must be treated with caution. -

A Journal of the Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the State Of

^o ^s«*s?>N>; fi^^; V|AViJV>j' * , 1 ' *^""' ' ... ' -,- -^p^- ^. 1 , journal'^ ^ ^^^ ^^ OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE LEGISLATIVE-COUNCIL OF THE t STATE O F NEW-JERSEY, CONVENED IN GENERAL ASSEMBLY AT TRENTON, ON TUESDAY THE TWENTY-SEVENTH DAY OF OCTOBER, M,DCC,XCV. BEING THE FJR8T AND SECOND SITTIKGS OF THE TWENTIETH SESSION. TRENTON: PRINTED BY M ATT HI AS DAT. M,DCC,XCVI. Ki \ I'u J± "v \ I LIST of Perfons returned as Members of the LEGISLATIVE-COUNCIL.. Tctcr Hariiig, Efex, John Condit, Middle/ex, Kpliraini Martin, Mor.mouthy m Eliflm Lawrence, v.p, Somiirfit, James Liini, Burlington^ O John Black, y. Gloucejler^ o Jofeph Cooper, Efquires, Salem, Tlyonias Sinnickfon, Matthew Whillden, Cape-'AIayy J3 Hunterdon, John I^ambcrt, Morris, Ellis Cook, Cumberland, Eli ElmcT, SuJiX, Charles Beard flee. LIST of Perfons returned as Members of the GENERAL ASSEMBLY. C Adam Boyd, Bergen, •^John Haring, ([^ Benjamin Blacklidge, C Ellas Dayton, < Jonas Wade, ^James Hedden, C Peter Vredenburgh, Middlefex, < Benjamin Maiming, ^ James Morgan, CTofeph StiUwell, Monmouth, ^Eliflia Walton, ^ James H. Imlay, r Henry Southard, Semerfet, •^ Peter D. Vroom, ^Robert Stockton, r Samuel Hough, Burlington, J. George Anderfon, (J^Stacy Biddle, r Abel Clement, Glouctjler, < Samuel French, Efquires. ^Thomas Somevs, r John Sinnickfon, Salem, <Elcazer Mayhew, C William Wallace, C Richard Townfend, Cafe-Mai^, jEleazer Hand, ^Reuben Townfend, r David Frazer, Hunterdon^ ^ Simon WyckofF, ^Benjamin VanClevc, r John Starke, Morris, < David Thomfon, ^John Debow, TEbenezer Elmer, Speaker, Cumberland, <. Benjamin Peck, ^Ebenezcr Scelcy, r William M'CuUough, Hujfex, ^ Peter Sharps, ([^ George Armftrong, JOURNAL( 3 ) ' . O F T H E PROCEEDINGS iO F THE LEGISLATIVE-COUNCIL O E T H E STATE OF NEW-JERSEY, Tuefdayy OSiober 27, 1795. -

John Cunditt

Outline Descendant Report for John Cunditt ..... 1 John Cunditt b: Abt. 1653 in Woodford, Wiltshire, England, d: 1713 in Newark, Essex, New Jersey; His will was proved 20 May, 1713 ..... +Deborah Potter b: Abt. 1655, d: England Or Wales, m: 1670 ........... 2 Peter Condit b: Abt. 1670 in England Or Wales, d: 1714 in Newark, Essex, New Jersey ........... +Mary Harrison b: 1675 in Branford, New Haven, Connecticut, d: 10 Dec 1761 in Newark, Essex, New Jersey, m: 1695 in New Jersey ................. 3 Samuel Condit b: 06 Dec 1696 in Newark, Essex, New Jersey, d: 18 Jul 1777 in Orange, Essex, New Jersey ................. +Mary Dodd b: 08 Nov 1698, d: 25 May 1755 ....................... 4 David Condit ....................... 4 Jonathan Condit ....................... 4 Daniel Condit ....................... 4 Jotham Condit ....................... 4 Samuel Condit ....................... 4 Martha Condit ................. 3 Peter Condit b: Bet. 1698-1699 in Newark, Essex, New Jersey, d: 11 Jul 1768 in Morristown, Morris, New Jersey; Peter CONDICT*, 69, Fever, 11 Jul from http:// dunhamwilcox.net/nj/morristown_nj_deaths.htm ................. +Phebe Dodd b: 1703 in Guilford, New Haven, Connecticut, d: 26 Jul 1768 in Morristown, Morris, New Jersey; Phebe, Widow of Peter CONDICT*, 65, Fever, 26 Jul from http:// dunhamwilcox.net/nj/morristown_nj_deaths.htm, m: 1724 in Newark, Essex, New Jersey ....................... 4 Silas Condit b: 07 Mar 1738 in Newark, Essex, New Jersey, d: 16 Sep 1801 in Morristown, Morris, New Jersey ....................... +Abigail Byram b: 19 Jan 1745 in Mendham, Morris, New Jersey, d: 05 Jan 1823 in Morristown, Morris, New Jersey, m: 16 Mar 1763 in Morristown, Morris, New Jersey ............................. 5 Marcia Condit b: 1763, d: 30 Jul 1793 in Morristown, Morris, New Jersey ...................... -

H. Doc. 108-222

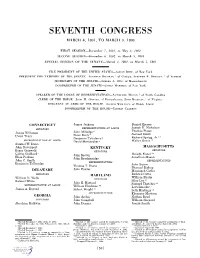

SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1801, TO MARCH 3, 1803 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1801, to May 3, 1802 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1802, to March 3, 1803 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1801, to March 5, 1801 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—AARON BURR, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ABRAHAM BALDWIN, 1 of Georgia; STEPHEN R. BRADLEY, 2 of Vermont SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 3 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN H. OSWALD, of Pennsylvania; JOHN BECKLEY, 4 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT James Jackson Daniel Hiester Joseph H. Nicholson SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas Plater James Hillhouse John Milledge 6 Peter Early 7 Samuel Smith Uriah Tracy 12 Benjamin Taliaferro 8 Richard Sprigg, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 13 David Meriwether 9 Walter Bowie Samuel W. Dana John Davenport KENTUCKY MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Roger Griswold SENATORS 5 14 Calvin Goddard John Brown Dwight Foster Elias Perkins John Breckinridge Jonathan Mason John C. Smith REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Tallmadge John Bacon Thomas T. Davis Phanuel Bishop John Fowler DELAWARE Manasseh Cutler SENATORS MARYLAND Richard Cutts William Eustis William H. Wells SENATORS Samuel White Silas Lee 15 John E. Howard Samuel Thatcher 16 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE William Hindman 10 Levi Lincoln 17 James A. Bayard Robert Wright 11 Seth Hastings 18 REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer Mattoon GEORGIA John Archer Nathan Read SENATORS John Campbell William Shepard Abraham Baldwin John Dennis Josiah Smith 1 Elected December 7, 1801; April 17, 1802. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

Votes and Proceedings of the General Assembly of the State of New-Jersey

( / /vw ' VOTES•*" A & D ROCEEDINGS I OF THE FIFTEENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE ATEV O F I NEW-JERSEY. \ta Seflion begun at Burlington the 26th Day of October, 1790, and continued by Adjournments. BEING THE FIRST SITTING. BURLINGTON: PRINTED BY NEALE AND LAWRENCE. M.DCC.XC. f'miwmmi ^SS» \ # 4 LIST of Perfons returned as Members of the LEGISLATIVE-COUNCIL, Bergen, Peter Haring, f Effex, John Condit, A liddlefex, Samuel Randolph, Monmouth, o Elifha Lawrence, V. P. Somcrfct, Frederick Frelinglmyfen, u Burlington, o William Newbold, c Gloiicejler, o Jofcph Ellis, \ Efquirss, Salem, ^ "i John Mayhew, Cape-May, Js Jeremiah Eldredge, Hunterdon, £""* John Lambert, Morris, William Woodhull, Cwnberla;;J, Samuel Ogden, Suffix, .Robert Hoops, IT ST of Perfons returned as Members of the GENERAL ASSEMBLY. f-ftaac Nicoll, Bergen, < John A. Benfon, C P'dmund W. Kingfland, ^-Jonas Wade, Effkx, < Jonathan Dayton, Speaker, (-Abraham Ogden, r Thomas M'Dowell, Middlcfex, } Peter Vredenbeigh, \John Runyan, Jofeph Stillwell, Monmouth, VPhomas Little, (John Imlay, (- Robert Stockton, Somerfet, ^ Peter D. Vroom, (James Linn, ^•Jofeph Biddle, Burlington, ^Daniel Newbold, ^George Anderfon, rjofeph Cooper, Glouccjler, 1 Thomas Clark, Squires, Samuel Hugg, (-•Samuel .Sharp, Salem, sjohn Smith, ^Benjamin Cripps, Townfend, r Elijah Cape May, ^Nezer Swain, < Richard Townfend, rjohn Anderfon, Hunterdon, ^Thomas Lowrey, ^John Taylor, r Ellis Cook, Morris, p Aaron Kitchel, ^•Jacob Arnold, rJohn Burgin, Cumberland, 3Ebenezer Elmer, CRichard Wood, jun. C Aaron Hankinfon, -

Ninth Congress March 4, 1805, to March 3, 1807

NINTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1805, TO MARCH 3, 1807 FIRST SESSION—December 2, 1805, to April 21, 1806 SECOND SESSION—December 1, 1806, to March 3, 1807 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1805, for one day only VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—GEORGE CLINTON, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL SMITH, 1 of Maryland SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 2 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN BECKLEY, 3 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT GEORGIA John Boyle SENATORS SENATORS John Fowler Matthew Lyon James Hillhouse Abraham Baldwin Thomas Sandford Uriah Tracy James Jackson 10 Matthew Walton REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE John Milledge 11 Samuel W. Dana REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE MARYLAND John Davenport Joseph Bryan 12 Calvin Goddard 4 Dennis Smelt 13 SENATORS Timothy Pitkin 5 Peter Early Robert Wright 20 Roger Griswold 6 David Meriwether Philip Reed 21 Lewis B. Sturges 7 Cowles Mead 14 Samuel Smith Jonathan O. Moseley Thomas Spalding 15 REPRESENTATIVES John Cotton Smith 8 William W. Bibb 16 Theodore Dwight 9 John Archer Benjamin Tallmadge KENTUCKY John Campbell Leonard Covington SENATORS Joseph H. Nicholson 22 DELAWARE John Breckinridge 17 Edward Lloyd 23 SENATORS 18 John Adair Patrick Magruder 19 Samuel White Henry Clay William McCreery James A. Bayard Buckner Thruston Nicholas R. Moore REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE REPRESENTATIVES Roger Nelson James M. -

Votes and Proceedings of the General Assembly of the State of New-Jersey

I, ; & & VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWENTIETH GENERAL ASSEMBLY STATEOF THE O F NETV-JERSET, At a SESSION begun at Trenton on the 27th Day of Oftober 1795, and continued by Adjournments. BEING THE FIRST SITTING. TRENTON: PRINTED BY ISAAC COLLINS. M.DCCXCV. •• ? • — , List of Persons returned as Members of the Legislative-Council. Bergen Peter Haring, Efex, John Condit, Middlefex, w Ephraim Martin, -1 Monmouth, a Elifha Lawrence, V. P. Somerfet, < James Linn, Pi Burlington, & John Black, O Glouccjler, ^ Jofeph Cooper, \ Esquires. Salem, O Thomas Sinnickfbn, Cape-May, X Matthew Whillden, Hunterdon, John Lambert, Morris, Ellis Cook, Cumberland, Eli Elmer, Sujfex, .Charles Beardflee, List of Persons returned as Members of the General Assembly. Adam Boyd, Bergen, John Haring, Benjamin Blacklidge, Elias Dayton, EJfex, Jonas Wade, James Hedden, C Peter Vredenburgh, Middlefex, -< Benjamin Manning, £ James Morgan, ~ Jofeph Stillwell, Monmouth, Elifha Walton, James H. Imlay, Henry Southard, Somerfet, Peter D. Vroom, _ Robert Stockton, f Samuel Hough, Burlington, -j George Anderfon, /Stacy Biddle, Abel Clement, Cloucejler, Samuel French, > Esquires. Thomas Somers, John Sinnickfon, Salem, Eleazer Mayhew, William Wallace, {Richard Townfend, Cape-May, Eleazer Hand, Reuben Townfend, {David Frazer, Hunterdon, Simon Wyckoff, Benjamin Van-Cleve, {John Starke, Morris, David Thomfon, John Debow, f Ebenezer Elmer, Speaker, Cumberland, < Benjamin Peck, £ Ebenezer Seeley, William M'Cullough, {" Sujfex, Peter Sharps, George Armftrong, n ; ( 5 ) V O T E S AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWENTIETH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE State of New-Jersey. TRENTON, Tuefday, OSiober 27, 1 795. THIS being the Time arid Place appointed by Law for the firft Meeting of the General AlTembly, the following Perfons attended, to wit, Benjamin Blacklidge, as one of the Reprefentatives of the County of Bergen ; Elias Dayton, Jonas Wade and James Hedden, as Reprefentatives for the County of Effex Benjamin Manning and Peter Vredenburgh, as two of the Reprefentatives for Stillwell, Elifha Walton and H. -

K:\Fm Andrew\11 to 20\13.Xml

THIRTEENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1813, TO MARCH 3, 1815 FIRST SESSION—May 24, 1813, to August 2, 1813 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1813, to April 18, 1814 THIRD SESSION—September 19, 1814, to March 3, 1815 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—ELBRIDGE GERRY, 1 of Massachusetts PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JOSEPH B. VARNUM, 2 of Massachusetts; JOHN GAILLARD, 3 of South Carolina SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, 4 of Massachusetts; CHARLES CUTTS, 5 of New Hampshire SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MOUNTJOY BAYLY, of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—HENRY CLAY, 6 of Kentucky; LANGDON CHEVES, 7 of South Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—PATRICK MAGRUDER, 8 of Maryland; THOMAS DOUGHERTY, 9 of Kentucky SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS DUNN, of Maryland DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT William H. Wells, 12 Dagsborough KENTUCKY REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE SENATORS SENATORS Chauncey Goodrich, 10 Hartford Thomas Cooper, Georgetown George M. Bibb, 18 Lexington David Daggett, 11 New Haven Henry M. Ridgely, Dover George Walker, 19 Nicholasville Samuel W. Dana, Middlesex William T. Barry, 20 Lexington GEORGIA Jessie Bledsoe, 21 Lexington REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE SENATORS Isham Talbot, 22 Frankfort Epaphroditus Champion, East 13 William H. Crawford, Lexington REPRESENTATIVES Haddam 14 William B. Bulloch, Savannah James Clark, Winchester John Davenport, Stamford 15 William W. Bibb, Petersburg Henry Clay, 23 Lexington Lyman Law, New London Charles Tait, Elbert Jonathan O. Moseley, East Haddam Joseph H. Hawkins, 24 Lexington Timothy Pitkin, Farmington REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Joseph Desha, Mays Lick Lewis B. Sturges, Fairfield William Barnett, Washington William P.