Viiinietzsche, Amor Fati and the Gay Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nietzsche's Revaluation of All Values Joseph Anthony Kranak Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Nietzsche's Revaluation of All Values Joseph Anthony Kranak Marquette University Recommended Citation Kranak, Joseph Anthony, "Nietzsche's Revaluation of All Values" (2014). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 415. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/415 NIETZSCHE’S REVALUATION OF ALL VALUES by Joseph Kranak A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin December 2014 ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE’S REVALUTION OF ALL VALUES Joseph Kranak Marquette University, 2014 This dissertation looks at the details of Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the revaluation of all values. The dissertation will look at the idea in several ways to elucidate the depth and complexity of the idea. First, it will be looked at through its evolution, as it began as an idea early in Nietzsche’s career and reached its full complexity at the end of his career with the planned publication of his Revaluation of All Values, just before the onset of his madness. Several questions will be explored: What is the nature of the revaluator who is supposed to be instrumental in the process of revaluation? What will the values after the revaluation be like (a rebirth of ancient values or creation of entirely new values)? What will be the scope of the revaluation? And what is the relation of other major ideas of Nietzsche’s (will to power, eternal return, overman, and amor fati) to the revaluation? Different answers to these questions will be explored. -

Eternal Recurrence and the Categorical Imperative Philip J

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Philosophy College of Arts & Sciences 3-2007 Eternal Recurrence and the Categorical Imperative Philip J. Kain Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/phi Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Kain, P. J. "Eternal Recurrence and the Categorical Imperative," The outheS rn Journal of Philosophy, 45 (2007): 105-116. This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Kain, P. J. "Eternal Recurrence and the Categorical Imperative," The outheS rn Journal of Philosophy, 45 (2007): 105-116., which has been published in final form at http://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-6962.2007.tb00044.x. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance With Wiley Terms and Conditions for self-archiving. https://www.pdcnet.org/collection/ authorizedshow?id=southernjphil_2007_0045_0001_0105_0116&pdfname=southernjphil_2007_0045_0001_0109_0120.pdf&file_type=pdf This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eternal Recurrence and the Categorical Imperative Philip J. Kain Santa Clara University I Nietzsche embraces the doctrine of eternal recurrence for the first time at Gay Science §341:1 The greatest weight.—What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: "This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unutterably small or great in your life will have to return to you, all in the same succession and sequence—even this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. -

Nietzsche and Amor Fati

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Essex Research Repository 1 [DRAFT: THIS VERSION MAY DIFFER IN MINOR WAYS FROM THE PUBLISHED VERSION (FORTHCOMING IN THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY), IN WHICH CASE THE LATTER SHOULD BE CONSIDERED AS AUTHORITATIVE] Nietzsche and Amor Fati Béatrice Han-Pile To the Memory of Mark Sacks Abstract: This paper identifies two central paradoxes threatening the notion of amor fati [love of fate]: it requires us to love a potentially repellent object (as fate entails significant negativity for us) and this, in the knowledge that our love will not modify our fate. Thus such love may seem impossible or pointless. I analyse the distinction between two different sorts of love (eros and agape) and the type of valuation they involve (in the first case, the object is loved because we value it; in the second, we value the object because we love it). I use this as a lens to interpret Nietzsche’s cryptic pronouncements on amor fati and show that while an erotic reading is, up to a point, plausible, an agapic interpretation is preferable both for its own sake and because it allows for a resolution of the paradoxes initially identified. In doing so, I clarify the relation of amor fati to the eternal return on the one hand, and to Nietzsche’s autobiographical remarks about suffering on the other. Finally, I examine a set of objections pertaining both to the sustainability and limits of amor fati, and to its status as an ideal. There is no doubt that Nietzsche considered the theme of amor fati [love of fate] of essential importance: he referred to it in his later work as his ‘formula for greatness in a human being’ (EH: 258), ‘the highest state a philosopher can attain’ (WP 1041), or again his ‘inmost nature’ (EH: 325). -

Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School April 2021 Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis William A. B. Parkhurst University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Parkhurst, William A. B., "Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis" (2021). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8839 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence: Methods, Archives, History, and Genesis by William A. B. Parkhurst A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Joshua Rayman, Ph.D. Lee Braver, Ph.D. Vanessa Lemm, Ph.D. Alex Levine, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 16th, 2021 Keywords: Fredrich Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, History of Philosophy, Continental Philosophy Copyright © 2021, William A. B. Parkhurst Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my mother, Carol Hyatt Parkhurst (RIP), who always believed in my education even when I did not. I am also deeply grateful for the support of my father, Peter Parkhurst, whose support in varying avenues of life was unwavering. I am also deeply grateful to April Dawn Smith. It was only with her help wandering around library basements that I first found genetic forms of diplomatic transcription. -

Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence Philip J

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Philosophy College of Arts & Sciences Spring 2007 Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence Philip J. Kain Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/phi Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Kain, P. J. "Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence," The ourJ nal of Nietzsche Studies, 33 (2007): 49-63. Copyright © 2007 The eP nnsylvania State University Press. This article is used by permission of The eP nnsylvania State University Press. http://doi.org/10.1353/nie.2007.0007 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence PHILIP J. KAIN I t the center ofNietzsche's vision lies his concept of the "terror and horror A of existence" (BT 3). As he puts it in The Birth of Tragedy: There is an ancient story that King Midas hunted in the forest a long time for the wise Silenus, the companion of Dionysus .... When Silenus at last fell into his hands, the king asked what was the best and most desirable of all things for man. Fixed and immovable, the demigod said not a word, till at last, urged by the king, he gave a shrill laugh and broke out into these words: "Oh, wretched ephemeral race, children of chance and misery, why do you compel me to tell you what it would be most expedient for you not to hear? What is best of all is utterly beyond your reach: not to be born, not to be, to be nothing. -

Nietzsche's Die Dionysische Weltanschauung

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Nietzsche’s Die dionysische Weltanschauung: Faith and Nihilism Part Two Nietzsche’s “Dionysian worldview” as an existentialist interpretation of meaning and purpose in reaction to the growing trend of Nihilism at the end of the 19th century Crane ROHRBACH A consequence of the Industrial Revolution in Europe was the focus on science and rationality in conditioning man’s relationship to the world, in creating a new identifying statute of culture with science, that the world of human life was the product of human action. It determined new principles of intellectual freedom for an eager desire to follow whatever ideas they brought forth and follow them wherever they led, even if they transgressed against the constraints of social and religious orthodoxies. Nietzsche examined premises of established ideas, re-examined them, relative to the social atmo- sphere of the dominance of the scientific status. But unlike Schopenhauer’s bleak skepticism of man’s historicism and scientism, Nietzsche sought to find some forms of affirmation for life despite the growing predominance of nihilism in western culture, that which Schopenhauer’s criticicism of historicism in his Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung expresses: that the history of man is superfluous to the essence of reality. — 43 — “A real philosophy of history [i.e., Humanity’s truth in reality] …consists, therefore, not in elevating the temporary aims of men into something eternal and absolute, and in constructing artificially and in imagination their advance to it through all complexities; but in the insight that history, not only in its execution but already in its essence, is mendacious…. -

Amor Fati: Love Thyself by Becoming What You Are! Nietzsche on the Freedom of the Will

Romanian Review of Social Sciences Vol. 7 (2017), No.13 rrss.univnt.ro AMOR FATI: LOVE THYSELF BY BECOMING WHAT YOU ARE! NIETZSCHE ON THE FREEDOM OF THE WILL Mihai NOVAC Lecturer, PHD, Nicolae Titulescu University – Bucharest ([email protected]) Abstract Nietzsche’s distinction between the master and the slave moralities is certainly one of his most notoriously famous moral and political notions. To claim that there are two main perspectives on the world, one belonging to the accomplished, the other to the unaccomplished side of humanity and, moreover, that the last two millennia of European alleged cultural progress constitute, in fact, nothing more than the history of the progressive permeation of our entire Weltanschauung, of our very values, thoughts and feelings by the so called slave morality, while all the more finding the virtue of this process in a future self-demise of this entire decadent cultural and human strain, is something that has shocked and enraged most of the ideological philosophers ever since. As such, at a certain moment, despite their substantial doctrinaire differences, almost everybody in the ideologized philosophical world, would agree on hating Nietzsche: he was hated by the Christians, for claiming that “God is dead”, by the socialists for treating their view as herd or slave mentality and denying the alleged progressively rational structure of the world, by the liberals much on the same accounts, by the ‘right wingers’ for his explicit anti-nationalism, by the anarchists for his ontological anti-individualism (i.e. dividualism), by the collectivists for his mockery of any gregarious existence, by the capitalists for his contempt for money and the mercantile worldview, by the positivists for his late mistrust in science and explicit illusionism (i.e. -

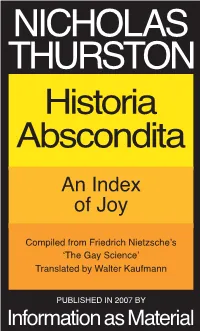

Historia Abscondita an Index of Joy

NICHOLAS THURSTON Historia Abscondita An Index of Joy Compiled from Friedrich Nietzsche’s ‘The Gay Science’ Translated by Walter Kaufmann PUBLISHED IN 2007 BY InformationasMaterial HISTORIA ABSCONDITA1 (An Index of Joy) BY Nicholas Thurston FIRST EDITION YORK 2007 1 Concealed, secret, or unknown history. What good is a book AN INDEX OF JOY Every great human being exerts a retroactive force: for his sake all of history is placed in the balance again, and a thousand secrets of the past crawl out of their hiding places—into his sunshine. There is no way of telling what may yet become part of history. Perhaps the past is still essentially undiscovered! So many retroactive forces are still needed! altruism, Americans, Abbruch, Zerstörung, Untergang, amor fati, Umsturz, amor intellectualis dei, accidens, amour-plaisir, accidents, amour-vanité, actions, anaesthetics, effect of, anarchists, actors, Andrade, E. N. daC., animals, mercy for, animals adaptability, and men, Aeschylus, aesthetics, anthem, German national, affirmation and renunciation, anthropomorphisms, age, anti-idealism, anti-Semitism, of founda- tions, Antony, Mark, agreement, law of, An-und Für-sich’s, air, virile, aphorisms, Ajax, Apollinian art, albatross, Apollo, Albigensian Crusade, appearance, Alcaeus, good will to, alcohol, applause, Alfieri, Count Vittorio, appropriation, Allah, Arabia, alpha and omega, Ararat, 1 2 inde X Archilochus, Bahnsen, Julius, architects, social, Baldwin, James Mark, architecture, Barnes, Hazel, Ariston of Chios, Bastille, Aristotle, Batz, Philipp, -

Amor Fati 2.Indd

Nietzsche’s Amor Fati: The Embracing of an Undecided Fate by Friedrich Ulfers and Mark Daniel Cohen published by The Nietzsche Circle, June 2007 AmorNietzsche’s fati The Embracing of an Undecided Fate by Friedrich Ulfers and Mark Daniel Cohen 1 Nietzsche’s Amor Fati here is in Nietzsche an unequivocal affirmation of life, and it would be Tprecisely wrong to say, “notwithstanding the equivocality that he injects into his every assertion,” for there is nothing in Nietzsche that withstands his equivocality. Yet, it speaks to the essence of Nietzsche’s posture to observe that there is nothing diffident or less than forthright in his work—he makes assertions, enormously complex assertions, and they are clearly intended to be taken as asserted. Nietzsche means what he says. It is his saying that bears the complexity in its method, which practices the undermining and enhancing of inherited terminology and philosophical principles, often in ploys of overt contradiction, to propose what is unequivocally meant. One must follow him in his every move, through each verbal gambit, to get at a meaning that always constitutes straight answers to straight questions, at a meaning that presumably requires the richness of literary strategy, of complicated saying, to be formulated at all. The idea dissolves without the verbal underpinning. It evaporates in the absence of his statement. It is so subtle, even as it is so clear and unequivocal once grasped. In short, nothing in Nietzsche goes without saying. One could be clever and say merely that, with Nietzsche, his very equivocality is itself equivocal, and it would be right to say so. -

Artaud's Nietzsche: Examining Manifestations of the Dionysian in the Theatre and Its Double

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2018 Artaud's Nietzsche: Examining Manifestations of the Dionysian in The Theatre and Its Double Cheyanne Noel Leonardo University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Recommended Citation Leonardo, Cheyanne Noel, "Artaud's Nietzsche: Examining Manifestations of the Dionysian in The Theatre and Its Double. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2018. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/5137 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Cheyanne Noel Leonardo entitled "Artaud's Nietzsche: Examining Manifestations of the Dionysian in The Theatre and Its Double." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in French. Mary K. McAlpin, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Adrian Del Caro, Gina M. Di Salvo Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Artaud’s Nietzsche: Examining Manifestations of the Dionysian in The Theatre and Its Double A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Cheyanne Noel Leonardo August 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 by Cheyanne Noel Leonardo All rights reserved. -

Stern: Nietzsche's Ocean, Strindberg's Open

BERLINER BEITRÄGE ZUR SKANDINAVISTIK Titel/ Nietzsche's Ocean, Strindberg's Open Sea title: Autor(in)/ Michael J. Stern author: Kapitel/ 4: »The Impossibility of Influence or How the Story Has Been Told« chapter: In: Stern, Michael J.: Nietzsche's Ocean, Strindberg's Open Sea. Berlin: Nordeuropa-Institut, 2008 ISBN: 3-932406-28-1 978-3-932406-28-7 Reihe/ Berliner Beiträge zur Skandinavistik, Bd. 13 series: ISSN: 0933-4009 Seiten/ 133–176 pages: © Copyright: Nordeuropa-Institut Berlin und Autoren © Copyright: Department for Northern European Studies Berlin and authors Diesen Band gibt es weiterhin zu kaufen. Section II: The Encounter between Strindberg and Nietzsche Chapter 4: The Impossibility of Influence or How the Story Has Been Told The significance of this encounter between Nietzsche and Strindberg falls along the fault lines of contemporary theoretical discourse. Questions concerning modernity and particularly the collision between religious and secular discourse emerge when we examine aspects of Strindberg’s protean production through the prism of Nietzsche’s thought. The prob- lem of what it means to be a being in the flow of time is highlighted in the two men’s work by the collision between two distinct ways of experienc- ing time: a linear, eschatological temporal construction and a circular, subjective experience of chronology. This collision expresses a modern, tragic view of existence. An understanding of tragedy refracted through a modernist lens shows itself to be the cornerstone of Nietzsche’s philoso- phy and the basis for Strindberg’s understanding of the self. While the importance of the relationship between Nietzsche and Strindberg has elicited some interest, there is no comprehensive inquiry into the confluence of these aspects of their thought. -

A Study of the Self in Nietzsche's Fatalistic

A STUDY OF THE SELF IN NIETZSCHE‘S FATALISTIC UNIVERSE OF ETERNAL RECURRENCE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ARGUN ABREK CANBOLAT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY JUNE 2009 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Ahmet İnam Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Assist. Prof. Dr. Barış Parkan Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Ahmet İnam (METU,PHIL) Assist. Prof. Dr. Barış Parkan (METU,PHIL) Assist. Prof. Dr. Ertuğrul Rufayi Turan(Ankara U.,DTCF) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Signature : iii ABSTRACT A STUDY OF THE SELF IN NIETZSCHE‘S FATALISTIC UNIVERSE OF ETERNAL RECURRENCE Canbolat, Argun Abrek M.A., Department of Phılosophy Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Barış Parkan June 2009, 106 Pages The doctrine of eternal recurrence is not only an aspect of Nietzsche‘s philosophy, but a notion that structures the base of his philosophy.