Design-Build Projects: a Comparison of Views Between South Australia and Singapore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shortage Occupations in Construction: a Cross-Industry Research Report

Shortage occupations in construction: A cross-industry research report Shortage occupations in construction: A cross-industry research report January 2019 1 Shortage occupations in construction: A cross-industry research report Summary This report provides the results of a survey to identify ° general labourer (SOC Code: 9120) occupations that are experiencing, or may experience ° quantity surveyors(SOC Code: 2433) shortages of available staff, in the UK construction sector. ° construction project manager(SOC Code: 2436) The findings of the report are based on the results of a cross-industry survey supported by 276 companies ° civil engineer (SOC Code: 5319) which collectively employ more than 160,000 ° bricklayer (SOC Code: 5312) workers. ° carpenter (SOC Code: 5315) Construction & building trades supervisors (SOC Code: 5330) are consistently reported as a shortage ° plant and machine operatives (SOC Code: occupation. This is true both now, and is forecast by 8229) respondents to be the case post-Brexit. ° Production managers and directors in construction (SOC Code: 1122) The research also found the following roles are frequently seen as shortage occupations: ° chartered surveyor (SOC Code: 2434). To address these issues, it is recommended that: ° Industry to work with UK Government and ° UK Government to consider appropriate other stakeholders to ensure that there are transition period to allow UK businesses to pathways for UK workers to fill the shortage adapt to the changing nature of migration, roles. with regular reassessment of shortage expected future skills supply and demand. ° Migration Advisory Committee to consider whether to include the above 10 priority roles ° UK Government to maintain commitment in future Shortage Occupation lists. -

Get to Know Our People

Meet The Team Get To Know Our People The people who give the Aston brand meaning, personality and life Our Team We are an award-winning team of Quantum and Delay Experts and Claims Practitioners, servicing clients and their projects both nationally and internationally. Our specialists are regularly acknowledged as Construction Experts by Who’s Who Legal. We invest in the professional development of our support teams across our offices, in order to offer the appropriate breadth and depth of experience to advise on a range of disputes across the infrastructure and construction industry. We are pleased to introduce you to the Aston Team. “We all feel extremely proud and honoured to have been recognised by our Professional Institution. I understand that this is the first year that this category has been available for organisations such as Aston Consult, who work predominantly in the field of Claims and Dispute Resolution and so to be recognised as the best in class makes it very special.” James Funge, Executive Director ASTON Consult Pty Ltd | Meet The Team | Our Team | 1 1. Our Skillset Our Team Dispute Contract Claims Expert Quantum and Mitigation and Arbitrator Adjudicator Management Witness Commercial and Procurement (Time and Cost) Resolution Management Simon Lowe Executive Director James Funge Executive Director Joe Briers Executive Director David Murray Director Nick Moulding Director Julian Hemms Director Simon Russell Director Alex Daniels Director Sean Murphy Snr Assoc. Director Eugene Cloete Snr Assoc. Director Matt MiniotasSnr Assoc. Director Yazeed Abdelhadi Snr Assoc. Director Sandra Hugo Snr Assoc. Director Suzanne Chinner Snr Assoc. Director Douglas Wilson Snr Assoc. -

Enhancing Building Services Cost Management Knowledge Among Quantity Surveyors

ENHANCING BUILDING SERVICES COST MANAGEMENT KNOWLEDGE AMONG QUANTITY SURVEYORS SUHAILA BINTI REMELI UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI MALAYSIA iv ENHANCING BUILDING SERVICES COST MANAGEMENT KNOWLEDGE AMONG QUANTITY SURVEYORS SUHAILA BINTI REMELI A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Science (Quantity Surveying) Faculty of Built Environment Universiti Teknologi Malaysia AUGUST 2013 vi Special dedicated to: My beloved parents, Ayah and Mak My dearest siblings, Abang Rizal, Kak Jue, Kak Ida, Abg Joe, Kak Eni, Abg Ang, Kak Ena, Adik Paih Who offered me unconditional love and support... My supportive supervisor, Dr. Sarajul Fikri Mohamed Who teach and guide me throughout the research... All my faithful friends, My dearest roommates, Nurizan, Mazlin, Khairiah, Nisa My Comrades, Shazwani, Ganiyu, Amirrul Amir, Faizal, Hayani, Dayah, Farah, Noien, Wani, Yong, Akma, Ridzuan, Qayyum, Hafiz and Shidah For their friendships and supportive that brightens my research life... vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT In the name of Allah, most benevolent and ever-merciful, All praises be to Allah Lords of the worlds. First and foremost, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Dr Sarajul Fikri Mohamed to be such inspirational, supportive, patient and being so consideration through my research journey to produce a quality work, generous advices, guidance, comments, patience, commitments and exposed me to the world of research. I would also like to thank my examiners who provided encouraging and constructive feedback. It is not an easy task, reviewing a thesis, and I am grateful for their thoughtful and detailed comments. This thesis was funded by grant by Universiti Teknologi Malaysia and I would like to endlessly thank university for the generous support. -

Civil, Architecture and Marine Engineering April 22–23, 2019 | Osaka, Japan

International conference on Civil, Architecture and Marine Engineering April 22–23, 2019 | Osaka, Japan A review of the performance of the price premium of “Green Buildings” – A Hedonic price model approach *Michael C.P. Sing1, Joseph H.L. Chan2 1Research Assistant Professor, Department of Building and Real Estate, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, China 2Lecturer, School of Professional Education and Executive Development, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, China Sustainable construction and green buildings have become increasingly popular in different sectors over the globe. Heightened awareness of environmental impacts of production and consumption pattern increases the willingness-to-pay premium for green products / services. The Building Environmental Assessment Method Plus (BEAM Plus) is a Hong Kong based green building assessment scheme which provides building users with a single performance label that demonstrates the overall quality of a building. Eco-labelled buildings are beneficial to developers, building occupants and the environment. Logically, the green certification attached to the buildings could be translated to a higher property value. It is expected buyers will be prepared to make a higher bid for green buildings than those without green building certification. This research work aims to explore the relationship of the effect of BEAM Plus certification on price premium in the private residential building sector. While buildings bear more unique characteristics, a hedonic price model is employed to estimate the extent to which each factor affects the price. A total of 320 transactions of private residential buildings in Hong Kong were sampled to illustrate the positive relationship between property price and the BEAM Plus certification with a hedonic price model. -

The Surveying Profession in the United Kingdom

Keynote Address The Surveying Profession in the United Kingdom INTRODUC~ON veying" first appeared in English and was described T IS A VERY GREAT PRIVILEGE to be at this Opening as relakg mainly to the ''management" of land and I ceremonyofyour 50th convention, bringing to- buildings. But before I turn to the profession his- gether as it does two of your long-established profes- torically, let me put into context the ~oyal~nstitu- sional societies to consider the immense subject em- tion of Chartered Surveyors (RICS)and its relevance braced by your theme, "Technology in Transition." When I was invited to present this paper I was In the UK, professional interests in the fields of not aware that that would be the theme, and at first surveying and mapping are primarily (but not ex- sight the relevance of how the surveying profession clusively) represented by the RICS,which is the only is organized in the United Kingdom may not be such body incorporated by Royal Charter. apparent. Indeed, this becomes even more ques- A Royal Charter is granted by the Sovereign and tionable in view of this audience being primarily confers on the incorporated body extensive powers concerned with surveying and mapping and related of self-regulation, including (a) determination of sciences whereas in the UK the profession of sur- standards for entry to the profession, (b) holding veying has a much broader base. qualifying examinations and accepting university It is, however, relevant that the way in which that degrees in lieu, (c) prescribing a code of conduct broader base evolved can be traced to a beginning and exercising disciplinary powers, and (d) pro- in an earlier era of transition in technology, the in- viding services for the profession. -

A Comparative Study of Construction Cost and Commercial Management Services in the UK and China

PERERA, S., ZHOU, L., UDEAJA, C., VICTORIA, M. and CHEN, Q. 2016. A comparative study of construction cost and commercial management services in the UK and China. London: RICS. A comparative study of construction cost and commercial management services in the UK and China. PERERA, S., ZHOU, L., UDEAJA, C., VICTORIA, M. and CHEN, Q. 2016 © 2016 Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors. This document was downloaded from https://openair.rgu.ac.uk Research May 2016 A Comparative Study of Construction Cost and Commercial Management Services in the UK and China 中英工程造价管理产业比较研究 GLOBAL/APRIL 2016/DML/20603/RESEARCH GLOBAL/APRIL rics.org/research A Comparative Study of Construction Cost and Commercial Management Services in the UK and China 中英工程造价管理产业比较研究 rics.org/research Report for Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors Report written by: Prof. Srinath Perera PhD MSc IT BSc (Hons) QS MRICS AAIQS Chair in Construction Economics [email protected] kimtag.com/srinath Dr. Lei Zhou Senior Lecturer Dr. Chika Udeaja Senior Lecturer Michele Victoria Researcher Northumbria University northumbria-qs.org Prof. Qijun Chen Director of Human Resource Department, Shandong Jianzhu University RICS Research team Dr. Clare Eriksson FRICS Director of Global Research & Policy [email protected] Amanprit Johal Funded by: Global Research and Policy Manager [email protected] Published by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) RICS, Parliament Square, London SW1P 3AD www.rics.org The views expressed by the authors are not necessarily those of RICS nor any body connected with RICS. Neither the authors, nor RICS accept any liability arising from the use of this publication. -

SCSI Conditions of Engagement Guidance

Conditions of Engagement for Chartered Project Management Surveyors 1st edition, 2013 Conditions of Engagement for Chartered Project Management Surveyors Published by the Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland No responsibility for loss or damage caused to any person acting or refraining from actions as a result of the material included in this publication can be accepted by the authors of SCSI. Published November 2013 © Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland (SCSI). Copyright in all or part of this publication rests with the SCSI save by prior consent of SCSI, no part or parts shall be reproduced by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, now known or to be advised. Acknowledgments Produced by the Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland Project Management Surveying Professional Group in conjunction with the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS). This document consists of material used in the RICS publication Project Manager Services, Standard Forms of Consultants Appointment. The SCSI would also like to thank the following Project Management Professional Group Committee members; ▪ Derry Scully, Bruce Shaw Partnership, Kestrel House, Clanwilliam Place, Dublin 2. ▪ Brendan McGing, Brendan McGing & Associates, 1-3 Fitzwilliam Street Lower, Dublin 2 ▪ Liam Murphy, LJM Quantity Surveyors and Project Management, Bray, Co. Wicklow. ▪ Kevin Sheridan, Independent consultant ▪ Greg Flynn, AECOM, 24 Lower Hatch Street, Dublin 2. ▪ Paul Mangan, Director of Buildings, Trinity College, Dublin 2. 3 Conditions of Engagement for Chartered Project Management Surveyors This Category of Service relates to the provision of Project Management Services by Chartered Project Management Surveyors which for the purposes of this Scale shall be hereinafter referred to as the Project Manager. -

Assistant Building Surveyor Job Description

Created February 2019 Updated February 2019 Issued March 2019 Final Version March 2019 Plymouth Community Homes JOB DESCRIPTION POSITION: Assistant Building Surveyor RESPONSIBLE TO: Chartered Building Surveyor LOCATION: Any PCH location SUMMARY OF ROLE To assist the Chartered and Senior Building Surveyors by developing the specialist professional knowledge for the strategic management of PCH built assets and to undertake routine surveying tasks in support of this goal. This requires an understanding of the nature of the tenancy agreements regarding property repairs, improvements, alterations, and use. The Assistant Building Surveyor requires a developing knowledge of; how to determine maintenance needs from both technical and functional perspectives, health and safety and other statutory requirements relevant to managed occupied residential property. They also require an understanding of how maintenance planning, procurement, and monitoring functions are formulated and operated. The Assistant Building Surveyor will undertake inspections of PCH properties under the supervision of a Chartered Building Surveyor. They require a functional knowledge of building construction and pathology in order that they can provide a reasoned analysis of defects and report on the likely resultant risks from failures in building fabric. The Assistant Building Surveyor should have a detailed working knowledge of the procurement routes and tendering procedures used on their projects and give reasoned advice on the appropriateness of various procurement routes. The Assistant Building Surveyor will also manage the tendering and negotiation process and present reports on the outcome under the supervision of a Chartered Building Surveyor. KEY TASKS To undertake the inspection of property and, working under the supervision of a Chartered Building Surveyor, provide detailed reasoned advice regards the management of that property to ensure PCH meets its statutory obligations and corporate asset management objectives. -

Building and Land Surveyor

Building and Land Surveyor This is a unique opportunity for a Surveyor with serious career ambitions and an entrepreneurial mindset. Our client offers advanced surveying solutions including topographical surveys, measured building surveys, utilities surveys, UAV surveys, laser scan surveys and building information modelling. Clients include leading architects, engineers, construction companies, government authorities, investors and commercial organisations across the United Kingdom. Essential requirements: • Proficient in measured building surveying, land and topographical surveying • A good knowledge of engineering principles and inspection techniques. • An ability to self-manage and take responsibility for project deliverables. • Be fully mobile and able to travel throughout the UK with full UK driving licence. Desired: • RICS Chartered Surveyor • Experience of LiDAR, still photography and 4K video, photogrammetric point clouds • Revit & BIM • Knowledge of photogrammetry data processing techniques • CAA Approved with a minimum 50hrs recorded flying time Responsibilities and tasks include: • Survey and inspection data processing and reporting • Providing technical support and project planning • Use varied surveying equipment, from traditional total stations to modern drone- mounted GPS mapping • Use data from a varied range of external sources, e.g. aerial photographs, laser scanners, satellite surveys • Measure land, recording aspects like angles, elevations, and relative distance • Perform surveys to collect data on man-made and natural features • Use digital mapping technologies • Equipment maintenance and software updates e.g. AirData and DJI Assistant You will be a Member of at least 2 of the following organisations: The Institution of Civil Engineers ICE / Chartered Institution of Civil Engineering Surveyors ICES / The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors RICS / The Chartered Institute of Building CIOB / The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers CIBSE. -

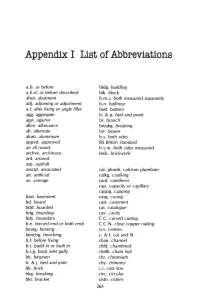

Appendix I List of Abbreviations

Appendix I List of Abbreviations a.b. as before bldg. building a.b.d. as before described blk. block abut. abutment b.m.s. both measured separately adj. adjoining or adjustment b.n. bullnose a.f. after fixing or angle fillet bott. bottom agg. aggregate b. & p. bed and point agst. against br. branch alice. allowance breakg. breaking alt. alternate brr. bearer alum. aluminium b.s. both sides appvd. approved BS British Standard air all round b.s.m. both sides measured archve. architrave bwk. brickwork ard. around asp. asphalt assctd. associated cal. plumb. calcium plumbate art. artificial calkg. caulking av. average cant. cantilever cap. capacity or capillary cappg. capping bast. basement casg. casing bd. board cast. casement bdd. boarded cat. catalogue bdg. boarding cav. cavity bdy. boundary C.C. curved cutting b.e. bossed end or both ends C.C.N. close copper nailing bearg. bearing ccs. centres benchg. benching c. & f. cut and fit b. f. before fixing chan. channel b.i. build in or built in chfd. chamfered b.i.g. back inlet gully chnlk. chain link bit. bitumen chr. chromium b. & j. bed and joint chy. chimney bk. brick c. i. cast iron bkg. breaking eire. circular bkt. bracket cistn. cistern 263 264 Building Quantities Explained c.j. close jointed dia. or diam. diameter clg. ceiling diag. diagonally cln. clean diagrm. diagram else bdd. close boarded diff. difference c. m. cement mortar dimnsd. dimensioned col. colour disch. discharge comb. combined dist. distance or distemper comm. commencing ditto. or do. that which comms. commons has been said before commsng. -

Retail Zoning for the Chartered Surveyor

SCSI Professional Guidance Retail Zoning for the Chartered Surveyor Information Paper Retail Zoning for the Chartered Surveyor Information Paper 2 | Retail Zoning for the Chartered Surveyor Published by Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland, 38 Merrion Square, Dublin 2, Ireland Tel: + 353 (0)1 644 5500 Email: [email protected] No responsibility for loss or damage caused to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of the material included in this publication can be accepted by the authors or the Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland. © Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland published May 2015. Copyright in all or part of this publication rests with the Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland and the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, and save by prior consent of the Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland and the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, no part or parts shall be reproduced by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, now known or to be devised. Retail Zoning for the Chartered Surveyor | 3 Contents Page Acknowledgments 4 SCSI Information Paper 4 Document Status defined 4 Introduction 5 Depth of Zone 5 Quantum discount for frontage to depth ratio 5 Kiosk/Cut Out Units 6 Unit Sizing 6 Number of Zones 6 Two level trading 6 Size limit zoning 6 Dual/Return Frontage 6 First floor rental 7 User 7 Masked or Shadow Areas 7 Angled or Irregular Shop Front 7 Evidence 7 Period Buildings/Non Standard Shopfront 7 Changing Levels 7 4 | Retail Zoning for the Chartered Surveyor Acknowledgements; SCSI Working -

2015 Christine Horkan Appel

Appeal No: VA17/5/312 AN BINSE LUACHÁLA VALUATION TRIBUNAL AN tACHTANNA LUACHÁLA, 2001 - 2015 VALUATION ACTS, 2001 - 2015 CHRISTINE HORKAN APPELLANT AND COMMISSIONER OF VALUATION RESPONDENT In relation to the valuation of Property No. 2200675, Retail (Shops) at Local No/Map Ref: Unit 2, Bellaghy, Achonry West, Tobercurry, County Sligo. JUDGMENT OF THE VALUATION TRIBUNAL ISSUED ON THE 23RD DAY OF JULY, 2018 BEFORE Eoin McDermott – FSCSI, FRICS, ACI Arb Ordinary Member 1. THE APPEAL 1.1 By Notice of Appeal received on the 10th day of October, 2017, the Appellant appealed against the determination of the Respondent pursuant to which the net annual value ‘(the NAV’) of the above relevant Property was fixed in the sum of €7,080. 1.2 The sole ground of appeal as set out in the Notice of Appeal is that the determination of the valuation of the Property is not a determination that accords with that required to be achieved by section 19 (5) of the Act because:- “the business is practically non existent and the rates are exorbitant Income down year on year Adjoining property vacant with (sic) years Located in cul-de-sac Charlestown has/is severely impacted since the economic downturn.” 1.3 The Appellant considers that the valuation of the Property ought to have been determined in the sum of €3,540. 2. REVALUATION HISTORY 2.1 On the 16th day of March, 2017, a copy of a valuation certificate proposed to be issued under section 24(1) of the Valuation Act 2001 (“the Act”) in relation to the Property was sent to the Appellant indicating a valuation of €7,080.