Histories of Imagination: Critical and Creative Approaches to Irish Art Writing in the Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S.Macw / CV / NCAD

Susan MacWilliam Curriculum Vitae 1 / 8 http://www.susanmacwilliam.com/ Solo Exhibitions 2012 Out of this Worlds, Noxious Sector Projects, Seattle F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, Open Space, Victoria, BC 2010 F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, aceart inc, Winnipeg Supersense, Higher Bridges Gallery, Enniskillen Susan MacWilliam, Conner Contemporary, Washington DC F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, NCAD Gallery, Dublin 2009 Remote Viewing, 53rd Venice Biennale 2009, Solo exhibition representing Northern Ireland 13 Roland Gardens, Golden Thread Gallery Project Space, Belfast 2008 Eileen, Gimpel Fils, London Double Vision, Jack the Pelican Presents, New York 13 Roland Gardens, Video Screening, The Parapsychology Foundation Perspectives Lecture Series, Baruch College, City University, New York 2006 Dermo Optics, Likovni Salon, Celje, Slovenia 2006 Susan MacWilliam, Ard Bia Café, Galway 2004 Headbox, Temple Bar Gallery, Dublin 2003 On The Eye, Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast 2002 On The Eye, Butler Gallery, Kilkenny 2001 Susan MacWilliam, Gallery 1, Cornerhouse, Manchester 2000 The Persistence of Vision, Limerick City Gallery of Art, Limerick 1999 Experiment M, Context Gallery, Derry Faint, Old Museum Arts Centre, Belfast 1997 Curtains, Project Arts Centre, Dublin 1995 Liptych II, Crescent Arts Centre, Belfast 1994 Liptych, Harmony Hill Arts Centre, Lisburn List, Street Level Gallery, Irish News Building, Belfast Solo Screenings 2012 Some Ghosts, Dr William G Roll (1926-2012) Memorial, Rhine Research Center, Durham, NC. 2010 F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, Sarah Meltzer Gallery, New York. -

The Life and Works of Beatrice Elvery, 1881-1920

Nationalism, Motherhood, and Activism: The Life and Works of Beatrice Elvery, 1881-1920 Melissa S. Bowen A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History May 2015 Copyright By Melissa S. Bowen 2015 Acknowledgments I am incredibly grateful for the encouragement and support of Cal State Bakersfield’s History Department faculty, who as a group worked closely with me in preparing me for this fruitful endeavor. I am most grateful to my advisor, Cliona Murphy, whose positive enthusiasm, never- ending generosity, and infinite wisdom on Irish History made this project worthwhile and enjoyable. I would not have been able to put as much primary research into this project as I did without the generous scholarship awarded to me by Cal State Bakersfield’s GRASP office, which allowed me to travel to Ireland and study Beatrice Elvery’s work first hand. I am also grateful to the scholars and professionals who helped me with my research such as Dr. Stephanie Rains, Dr. Nicola Gordon Bowe, and Rector John Tanner. Lastly, my research would not nearly have been as extensive if it were not for my hosts while in Ireland, Brian Murphy, Miriam O’Brien, and Angela Lawlor, who all welcomed me into their homes, filled me with delicious Irish food, and guided me throughout the country during my entire trip. List of Illustrations Sheppard, Oliver. 1908. Roisin Dua. St. Stephen's Green, Dublin. 2 Orpen, R.C. 1908. 1909 Seal. The Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland, Dublin. -

An Artistic Praxis: Phenomenological Colour and Embodied Experience

Journal of the International Colour Association (2017): 17, 150-200 Balabanoff An Artistic Praxis: Phenomenological colour and embodied experience Doreen Balabanoff Faculty of Design, OCAD University, Toronto, Canada Email: [email protected] Artistic knowledge resides within the works that a visual artist makes. .Verbalising or discussing that knowledge is a separate exercise, often left to others, who make their own interpretations and investigations. In this introspective study of artworks spanning four decades, I look into and share insight about a practice in which knowledge about colour, light and spatial experience was developed and utilised. The process of action, reflection and new application of gained knowledge is understood as a praxis—a practice aimed at creating change in the world. The lessons learned are about human embodied experience of light, colour and darkness in spatial environments. The intent of the study (as of the artwork) is enhancement of our capacities for creating sensitive and enlivening space for human life experience and human flourishing, through understanding and use of colour and light as complex environmental phenomena affecting our mind/body/psyche. Four themes arose from reflecting upon the work. These are, in order of discussion: (1) Image and Emanation, (2) Resonance and Chord, (3) Threshold and Veil, and (4) Projection, Reflection, Light and Time. My findings include affirmation that a Goethian science (phenomenological, observational) approach to investigating and unconcealing tacit knowledge—embedded in an artistic praxis and its outcomes—has value for developing a deeper understanding of environmental colour and light. Such knowledge is important because environmental design has impact upon our bodies, our minds and our life experience. -

West of Ireland Paintings at the National Gallery of Ireland from 1800 to 2000

West of Ireland Paintings at the National Gallery of Ireland from 1800 to 2000 I The West of Ireland National Gallery of Ireland / Gailearaí Náisiúnta na hÉireann West of Ireland Paintings at the National Gallery of Ireland from 1800 to 2000 Marie Bourke With contributions by Donal Maguire And Sarah Edmondson II Contents 5 Foreword, Sean Rainbird, Director, National Gallery of Ireland 23 The West as a Significant Place for Irish Artists Contributions by Donal Maguire (DM), Administrator, Centre for the Study of Irish Art 6 Depicting the West of Ireland in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Dr Marie Bourke, Keeper, Head of Education 24 James Arthur O’Connor (1792–1841), The Mill, Ballinrobe, c.1818 25 George Petrie (1790–1866), Pilgrims at Saint Brigid’s Well, Liscannor, Co. Clare, c.1829–30 6 Introduction: The Lure of the West 26 Frederic William Burton (1816–1900), In Joyce Country (Connemara, Co. Galway), c.1840 6 George Petrie (1790–1866), Dún Aonghasa, Inishmore, Aran Islands, c.1827 27 Frederic William Burton (1816–1900), The Aran Fisherman’s Drowned Child, 1841 8 Timeline: Key Dates in Irish History and Culture, 1800–1999 28 Augustus Burke (c.1838–1891), A Connemara Girl 10 Curiosity about Ireland: Guide books, Travel Memoirs 29 Bartholomew Colles Watkins (1833–1891), A View of the Killaries, from Leenane 10 James Arthur O’Connor (1792–1841), A View of Lough Mask 30 Aloysius O’Kelly (1853–1936), Mass in a Connemara Cabin, c.1883 11 Frederic William Burton (1816–1900), Paddy Conneely (d.1850), a Galway Piper 31 Walter Frederick Osborne (1859–1903), A Galway Cottage, c.1893 32 Jack B. -

Joseph Maunsell Hone Papers P229 UCD ARCHIVES

Joseph Maunsell Hone Papers P229 UCD ARCHIVES [email protected] www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 2009 University College Dublin. All Rights Reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Biographical History iv Archival History iv CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and Content v System of Arrangement vi CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access vii Language vii Finding Aid vii DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s Note vii iii CONTEXT Biographical history Born in Dublin in February 1882, Joseph Maunsell Hone was educated at Wellington and Jesus College, Cambridge and began a writing career which gained him a reputation as a leading figure of the Irish literary revival. He wrote well regarded biographies of George Moore (1939), Henry Tonks (1936), and W.B. Yeats (1943) with whom he was on terms of close friendship. His political writings included books on the 1916 rebellion, the Irish Convention, and a history of Ireland since independence, published in 1932. He had a strong interest in philosophy, translating Daniel Halévy’s life of Nietzsche and working with Arland Ussher on an anthology of philosophers which was never completed. He was elected President of the Irish Academy of Letters in 1957. With George Roberts and Stephen Gwynn, he co-founded Maunsel & Company, publishers, and served as its chairman. The company published more than five hundred titles to become Ireland’s largest publishing house, publishing works by all the revival’s leading figures. The imprint later changed to Maunsel & Roberts. Joseph Hone died in March 1959 and was survived by his wife Vera (neé Brewster), a noted beauty from New York who he had married in 1911. -

Stained Glass in Ireland

Stained Glass in Ireland By Coral - Daphne – Sofie – Uta Participant teachers in English Matters’ Programme Dublin, Ireland What? • art form • coloured glass • mosaic stained glass art can be: • Classic • Modern • Smooth • Painted • Rough • … A little bit of history… • Real origins of stained glass are lost • Egyptians and the Romans • 7th century churches and monasteries in Britain • Medieval times: western churches & mosques • 19th-20th century: revival Stained Glass in Ireland St Theresa’s, Dublin National Library, Dublin (Harry Clarke) Bewley’s Café, (Harry Clarke) Grafton Str., Dublin The An Túr Gloine ("Tower of Glass") cooperative studio • 1901 throughout the first half of the 20th century. • artists included Michael Healy, Evie Hone, Beatrice Elvery, Wilhelmina Geddes and founder Sarah Purser. • hoped to provide an alternative to the commercial stained glass imported from England and Germany • "perhaps the most noteworthy example of the newly- awakened desire to foster Irish genius" • Influences: Arts and Crafts Movement, Irish revivalism and the artistic tradition of Celtic manuscript illumination. Influences Design for Trellis Wallpaper, William Morris, 1862 Proserpine, Dante Gabriel Rossetti Harry Clarke (1889-1931) • studied at Belvedere College and the Dublin Metropolitan School of art. • commissions even outside Ireland (Australia, US) • also an illustrator • fine detail of his drawing use of rich colours (especially deep blues) an innovative integration of the window leading • influenced by the Art Nouveau and Art Deco movements the French Symbolist movement the Arts and Crafts movement and the Pre-Raphaelites in Britain the revival of the Celtic tradition Medieval as well as Gothic art Clarke’s Famous Works The Geneva Window St. -

WILLIAM SCOTT (B.1913 Greenock, Scotland)

WILLIAM SCOTT (b.1913 Greenock, Scotland) EDUCATION Belfast College of Art Royal Academy Schools (1935) SELECT SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Paintings and Drawings: Fifties Through Eighties, Anita Rogers Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Verey Gallery, Eton College, Form – Colour – Space, Windsor, UK 2016 Fermanagh County Museum, William Scott: The Early Years, Enniskillen, Northern Ireland 2015 Fermanagh District Council Town Hall, William Scott Paintings at Enniskillen’s Town Hall, Enniskillen, Northern Ireland 2014 Pallant House gallery, Three pears and a Pan, 1955, Chichester, UK 2013 The Gordon Gallery, the Altnagelvin Mural, Derry, Northern Ireland 2013 The Ulster Museum, William Scott: Centenary Exhibition, Belfast, Northern Ireland 2013 The Hepworth Wakefield, William Scott, Wakefield, UK 2013 McCaffrey Fine Art, William Scott: Domestic Forms, New York, NY 2013 Victoria Art Gallery, William Scott: Simplicity and Subject, Bath, UK 2013 Denenberg Fine Arts, William Scott Works on Paper 1953-1986, Los Angeles, CA 2013 Karsten Schubert, William Scott 1950s Nude Drawings, London, UK 2013 Jerwood Gallery, William Scott: Divided Figure, Hastings, UK 2013 Enniskillen Castle Museum, Full-Circle: William Scott Centenary Exhibition, Enniskillen, Northern Ireland 2013 Tate St Ives, William Scott, and touring: Hepworth Wakefield; Ulster Museum, Belfast, Northern Ireland 2012 McCaffrey Fine Art at Frieze Masters, William Scott, London, UK 2010 McCaffrey Fine Art, William Scott, New York, NY 2009 F.E. McWilliam Gallery and Studio, William Scott in Ireland. Paintings, Drawings Gouaches and Lithographs 1938–1979, Banbridge, Northern Ireland 2006 Fermanagh County Museum, Celebrating William Scott: Paintings from Fermanagh County Museum, Enniskillen, Northern Ireland 2005 Denise Bibro Fine Art, William Scott Works on Paper, New York, NY 2005 Lorenzelli Arte, William Scott La voce dei colori, Milan, Italy 2005 Archeus Fine Art, William Scott. -

SU407 INTRODUCTION to ART in IRELAND (3 Credits)

SU407 INTRODUCTION TO ART IN IRELAND (3 Credits) COURSE OBJECTIVE: This course will trace the development of Irish art from Newgrange to the 2009 Venice Biennale. In the first part of the course students will learn to appraise and evaluate a broad spectrum of prehistoric art and the outstanding artistic achievements of the ‘Golden Age’ of Irish art; the Book of Kells, the Tara Brooch and Irish High Crosses. The second half of the course will focus on how the ‘rediscovery’ of this early artistic legacy informed later artists, culminating in the ‘Celtic Revival’ of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries before moving on to the development of modern art in Ireland, examining the work of Jack Yeats, Mainie Jellett, and many others. The course will conclude with an overview of trends in contemporary Irish art. A key question underlying the various strands of the course will be the development of a distinctly Irish cultural identity in the visual arts and the influence of international trends on Irish artists throughout the ages. COURSE OUTLINE: Week 1 Introductory lecture Passage Grave Art Bronze Age Gold Work FIELD SEMINAR: NATIONAL MUSEUM & NATIONAL GALLERY Week 2 La Tène Art: The Earliest Art of the Celts Irish Art AD 300-500: the Iron Age to Early Christian Transition The Golden Age of Irish Art The Work of Angels: Early Christian Manuscript Art Week 3 Celtic High Crosses: Ornament, Symbolic Significance and Iconography Turning Points in Irish Art The Celtic Revival: Motifs and Symbols The Celtic Revival: People and Landscape Week 4 The Irish Impressionists and the Belle Epoque Jack Yeats Realism, Nationalism and the West Week 5 Mainie Jellett and the Modernists Post War Trends and Contemporary Art ASSESSMENT COURSE TEXTS: Passage Grave Art Jones, C. -

July Edition 2017

Alan J. Poole Promoting British & Irish Contemporary Glass. 43 Hugh Street, London SW1V 1QJ. ENGLAND. Tel: (00 44) Ø20 7821 6040. Email: [email protected] British & Irish Contemporary Glass Newsletter. A monthly newsletter listing information relating to British & Irish Contemporary Glass events and activities, within the UK, Ireland and internationally. Covering British and Irish based Artists, those living elsewhere and, any foreign nationals that have ever resided or studied for any period of time in the UK or Ireland. JULY EDITION 2017. * indicates new and amended entries since the last edition. EXHIBITIONS, FAIRS, MARKETS & OPEN STUDIO EVENTS. 2016. 17/09/1603/09/17. Summer 2017. Ebeltoft Glasmuseet Collection Exhibition. inc: Lene Bødker. National Glass Centre. Sunderland. GB. Tel: 0191 515 5555. Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.nationalglasscentre.com/about/whatson/details/?id=740&to=2016-10- 18%2000:00:00&from=2016-10-18%2010:00:00 2017. 04/02/1704/09/17. "Glass Microbiology". Luke Jerram Solo Exhibition. The Box @ Bristol Science Centre. Bristol. GB. Tel: 0117 915 1000. Email: [email protected] Website: www.at-bristol.org.uk/event/box-presents-glass-microbiology 18/021731/12/17. "Companion Pieces". Mixed Media Permanent Collection Selected Exhibition. inc: Max Jacquard, Alison Kinnaird M.B.E. & Rachael Woodman. Shipley Art Gallery. Gateshead. GB. Tel: 0191 477 1495. Email: [email protected] Website: https://shipleyartgallery.org.uk/whats-on/companion-pieces 25/03/1701/10/17. "Jewellery: Wearable Glass". inc: James Maskrey, Joanne Mitchell, Ayako Tani & Angela Thwaites. University Of Sunderland. National Glass Centre. Sunderland. GB. Tel: 0191 515 5555. -

August Edition 2017

Alan J. Poole Promoting British & Irish Contemporary Glass. 43 Hugh Street, London SW1V 1QJ. ENGLAND. Tel: (00 44) Ø20 7821 6040. Email: [email protected] British & Irish Contemporary Glass Newsletter. A monthly newsletter listing information relating to British & Irish Contemporary Glass events and activities, within the UK, Ireland and internationally. Covering British and Irish based Artists, those living elsewhere and, any foreign nationals that have ever resided or studied for any period of time in the UK or Ireland. AUGUST EDITION 2017. * indicates new and amended entries since the last edition. EXHIBITIONS, FAIRS, MARKETS & OPEN STUDIO EVENTS. 2016. 17/09/1603/09/17. Summer 2017. Ebeltoft Glasmuseet Collection Exhibition. inc: Lene Bødker. National Glass Centre. Sunderland. GB. Tel: 0191 515 5555. Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.nationalglasscentre.com/about/whatson/details/?id=740&to=2016-10- 18%2000:00:00&from=2016-10-18%2010:00:00 2017. 04/02/1704/09/17. "Glass Microbiology". Luke Jerram Solo Exhibition. The Box @ Bristol Science Centre. Bristol. GB. Tel: 0117 915 1000. Email: [email protected] Website: www.at-bristol.org.uk/event/box-presents-glass-microbiology 18/021731/12/17. "Companion Pieces". Mixed Media Permanent Collection Selected Exhibition. inc: Max Jacquard, Alison Kinnaird M.B.E. & Rachael Woodman. Shipley Art Gallery. Gateshead. GB. Tel: 0191 477 1495. Email: [email protected] Website: https://shipleyartgallery.org.uk/whats-on/companion-pieces 25/03/1701/10/17. "Jewellery: Wearable Glass". inc: James Maskrey, Joanne Mitchell, Ayako Tani & Angela Thwaites. University Of Sunderland. National Glass Centre. Sunderland. GB. Tel: 0191 515 5555. -

M.Phil. in Art History Art + Ireland Handbook 2020-2021

School of Histories and Humanities Department of History of Art and Architecture M.Phil. in Art History Art + Ireland Handbook 2020-2021 Contents Overview ............................................................................................................................ 3 General requirements ........................................................................................................ 4 Assessment submission .............................................................................................................. 4 Regulatory notification ............................................................................................................... 4 Contacts ............................................................................................................................. 5 Staff contact information and research interests: ..................................................................... 5 Further information about location and facilities ...................................................................... 7 Programme structure ......................................................................................................... 8 Components ............................................................................................................................... 8 Credit System (ECTS) .................................................................................................................. 8 Modules ............................................................................................................................ -

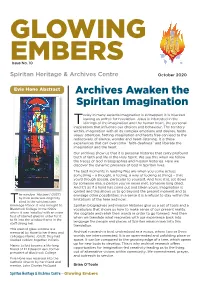

Embers No 10 Sept 2020 16Pp A4 Newsletter Layout 1

GLOWING EMBERS Issue No. 10 Spiritan Heritage & Archives Centre October 2020 Evie Hone Abstract Archives Awaken the Spiritan Imagination oday in many aspects imagination is kidnapped; it is hijacked leaving us unfree for revelation. Jesus is interested in the Tstirrings of the imagination and the human heart, the personal inspirations that influence our choices and behaviour. The territory within, imagination with all its complex emotions and desires, holds Jesus’ attention. Setting imagination and hearts free can lead to the rediscovery of silence, wonder and heart-listening. It is these experiences that can overcome `faith-deafness` and liberate the imagination and the heart. Our archives show us that it is personal histories that carry profound truth of faith and life in the Holy Spirit. We see this when we follow the traces of God in biographies and mission histories. Here we discover the dynamic presence of God in Spiritan lives. The best moments in reading files are when you come across something – a thought, a feeling, a way of looking at things – that you’d though special, particular to yourself. And here it is, set down by someone else, a person you’ve never met, someone long dead. And it’s as if a hand has come out and taken yours. Imagination is ignited and this allows us to go beyond the present moment and to he window ‘Abstract’ (1937) envisage other possibilities; in a sense it is a refusal to stay within the by Evie Hone was originally limitations of the here and now. Tsited in the scholasticate, Kimmage Manor.