Maryland's CWA Section 303(D) Program: Prioritizing Impairments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Summary for Youghiogheny River Fisheries Management Plan 2015

Executive Summary for Youghiogheny River Fisheries Management Plan 2015 The purpose of the 2012 and 2014 surveys of the Youghiogheny River was to evaluate water quality and fish species occurrence in Sections 02 through 06, assess the river’s naturally reproducing gamefish populations (particularly Smallmouth Bass and Walleye), assess the results of fingerling stocking of Brown Trout and Rainbow Trout in Sections 02 to 05 (from the mouth of the Casselman River downstream to the dam at South Connellsville), assess the efficacy of annual Muskellunge stocking in Section 06 (from the dam at South Connellsville downstream to the mouth at McKeesport), and to update the fisheries management recommendations for the Youghiogheny River. All of the section and site data for the Youghiogheny River sampled in 2012 and 2014 were improved over the historic sampling numbers for water quality, fish diversity, and fish abundance. Smallmouth Bass made up the bulk of the available fishery at all sites sampled in 2012 and 2014. The water quality improvement was in large part due to the reduction of acid mine drainage from the Casselman River. This improvement in alkalinity was observed in the Youghiogheny River at Section 02 just below the mouth of the Casselman River, with an increase to 20 mg/l in 2012 from 11 mg/l in 1989. Section 03 (from the confluence of Ramcat Run downstream to the Route 381 Bridge at Ohiopyle) alkalinity improved from 13 mg/l in 1989 to 22 mg/l in 2012. Recreational angling in the Youghiogheny River for a variety of species has increased over the last fifteen years based on local reports. -

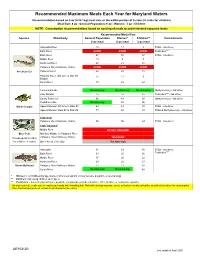

Recommended Maximum Fish Meals Each Year For

Recommended Maximum Meals Each Year for Maryland Waters Recommendation based on 8 oz (0.227 kg) meal size, or the edible portion of 9 crabs (4 crabs for children) Meal Size: 8 oz - General Population; 6 oz - Women; 3 oz - Children NOTE: Consumption recommendations based on spacing of meals to avoid elevated exposure levels Recommended Meals/Year Species Waterbody General PopulationWomen* Children** Contaminants 8 oz meal 6 oz meal 3 oz meal Anacostia River 15 11 8 PCBs - risk driver Back River AVOID AVOID AVOID Pesticides*** Bush River 47 35 27 PCBs - risk driver Middle River 13 9 7 Northeast River 27 21 16 Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor AVOID AVOID AVOID American Eel Patuxent River 26 20 15 Potomac River (DC Line to MD 301 1511 9 Bridge) South River 37 28 22 Centennial Lake No Advisory No Advisory No Advisory Methylmercury - risk driver Lake Roland 12 12 12 Pesticides*** - risk driver Liberty Reservoir 96 48 48 Methylmercury - risk driver Tuckahoe Lake No Advisory 93 56 Black Crappie Upper Potomac: DC Line to Dam #3 64 49 38 PCBs - risk driver Upper Potomac: Dam #4 to Dam #5 77 58 45 PCBs & Methylmercury - risk driver Crab meat Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 96 96 24 PCBs - risk driver Crab "mustard" Middle River DO NOT CONSUME Blue Crab Mid Bay: Middle to Patapsco River (1 meal equals 9 crabs) Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor "MUSTARD" (for children: 4 crabs ) Other Areas of the Bay Eat Sparingly Anacostia 51 39 30 PCBs - risk driver Back River 33 25 20 Pesticides*** Middle River 37 28 22 Northeast River 29 22 17 Brown Bullhead Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 17 13 10 South River No Advisory No Advisory 88 * Women = of childbearing age (women who are pregnant or may become pregnant, or are nursing) ** Children = all young children up to age 6 *** Pesticides = banned organochlorine pesticide compounds (include chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, or heptachlor epoxide) As a general rule, make sure to wash your hands after handling fish. -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

7 Sensitive Areas Garrett County’S Physical Landscape Is Characterized by Mountainous Ridges, Stream Valleys, Extensive Forests, and Productive Agricultural Areas

2008 Garrett County Comprehensive Plan 7 Sensitive Areas Garrett County’s physical landscape is characterized by mountainous ridges, stream valleys, extensive forests, and productive agricultural areas. The County is home to the four highest mountains in Maryland, the state’s first designated Scenic and Wild River (the Youghiogheny River), and the state’s largest freshwater lake (Deep Creek Lake). These features are scenic and recreational resources for the County’s residents and visitors, and many are also environmentally sensitive. The Planning Act of 1992 and subsequent legislation requires each comprehensive plan in Maryland to establish goals and policies related to sensitive environmental areas, specifically addressing: • Steep slopes, • Streams, wetlands, and their buffers, • 100-year floodplains, • The habitat of threatened or endangered species, • Agricultural and forest land intended for resource protection or conservation, and • Other areas in need of special protection. The County’s Sensitive Areas Ordinance (adopted in 1997) and Floodplain Management Ordinance (adopted in 1991) provide detailed guidance for development affecting these sensitive areas. This chapter updates the 1995 Plan’s description of the County’s sensitive areas, and, in conjunction with the Water Resources and Land Use chapters of this Plan, further strengthens policies to protect sensitive areas. This chapter includes a discussion of ridgelines as a sensitive area in need of protection. 7.1 Goals and Objectives The County’s sensitive areas goal is: Continue to protect Garrett County’s sensitive environmental resources and natural features. The objectives for achieving this goal are: 1. Limit development in and near sensitive environmental areas, including steep slopes, streams, wetlands, 100-year floodplains, and the habitats of threatened or endangered species. -

Paul F. Ziemkiewicz and David L. Brant2

THE CASSELMAN RIVER RESTORATION PROJECT1 Paul F. Ziemkiewicz and David L. Brant2 Abstract: The area along the Casselman River between Boynton and Meyersdale, PA was extensively mined in the late 1800's to early 1900's. The mining operations were room and pillar underground mining primarily on the Pittsburgh coal seem. The mined out area is approximately 5,000 acres in this deep mine complex (Shaw Mines Complex ‐ SMQ. Three tributaries to the Casselman River are impacted by acid mine drainage (AMD). Two of them are being restored primarily by re‐mining and the third has open limestone channels (OLCs) installed to remove part of the AMD produced in the SMC. Keywords: Open Limestone Channels, Re‐mining, Acid Mine Drainage 1Paper presented at West Virginia Surface Mine Drainage Task Force Symposium. Morgantown, WV, April 15 ‐ 16, 1997. 2Paul F. Ziemkiewicz, Ph.D., Director, David L. Brant, Research Associate, National Mine Land Reclamation Center, West Virginia University, P.O. Box 6064, Morgantown,WV 26506‐6064 Introduction Prior to the spring of 1993, the Casselman River was starting to rejuvenate between Rockwood and Confluence, PA. It was a stockable fishery in this region and upstream of Boynton, PA. The water quality in area between Boynton and Rockwood, although improving, was not suitable for sustaining fish life before the catastrophic discharge of acid mine drainage (AMD). The May 1993 acidic discharge occurred as a result of a rise in the local watertable due to a heavy snow cover that followed several years of below normal snowfall. The minerals in the long ‐abandoned deep mine (Shaw Mines Complex ‐ SMQ oxidized during the drier summer and leached into solution as the watertable increased. -

Pennsylvania State Parks

Pennsylvania State Parks Main web site for Dept. of Conservation of Natural Resources: http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/stateparks/parks/index.aspx Main web site for US Army Corps of Engineers, Pittsburgh District: http://www.lrp.usace.army.mil/rec/rec.htm#links Allegheny Islands State Park Icon#4 c/o Region 2 Office Prospect, PA 16052 724-865-2131 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/stateparks/parks/alleghenyislands.aspx Recreational activities Boating The three islands have a total area of 43 acres (0.17 km²), with one island upstream of Lock and Dam No. 3, and the other two downstream. The park is undeveloped so there are no facilities available for the public. At this time there are no plans for future development. Allegheny Islands is accessable by boat only. Group camping (such as with Scout Groups or church groups) is permitted on the islands with written permission from the Department. Allegheny Islands State Park is administered from the Park Region 2 Office in Prospect, Pennsylvania. Bendigo State Park Icon#26 533 State Park Road Johnsonburg, PA 15845-0016 814-965-2646 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/stateparks/parks/bendigo.aspx Recreational activities Fishing, Swimming, Picnicking The 100-acre Bendigo State Park is in a small valley surrounded with many picturesque hills. About 20 acres of the park is developed, half of which is a large shaded picnic area. The forest is predominantly northern hardwoods and includes beech, birch, cherry and maple. The East Branch of the Clarion River flows through the park. -

River Conservation Plan the Middle Youghiogheny River Corridor

RIVER CONSERVATION PLAN THE MIDDLE YOUGHIOGHENY RIVER CORRIDOR EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This River Conservation Plan has been prepared by Paul C. Rizzo Associates under contract to the Chestnut Ridge Chapter of Trout Unlimited (CRTU). Preparation of the Plan has been funded by a River Conservation Planning Grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR). The formulation of the Plan has been directed by the CRTU Plan Steering Committee taking into account the data, thoughts, and ideas offered by the local municipalities and governmental agencies and citizens residing in the Corridor. The overall response to this planning effort has been excellent as all of the concerned and affected parties have a dedicated, sincere interest in protecting, promoting and improving the resources of the Corridor. The Somerset County Conservancy was responsible for securing the funding through the DCNR River Conservation Program. A portion of the funds granted to the Somerset County Conservancy was provided to the CRTU to facilitate preparing the Middle Youghiogheny River Corridor River Conservation Plan. The Somerset County Conservancy is dedicated to the preservation and conservation of the natural resources in Somerset County and the surrounding region. The Southern Alleghenies Conservancy is acting as the Grant Administrator for this project. The Middle Youghiogheny River, often referred to as the “Yough”, is a valuable environmental and economic national resource. The Yough is a high gradient river that flows from the Appalachian Mountains into southwestern Pennsylvania, eventually feeding into the Monongahela River at McKeesport, PA. The Yough lacks significant natural buffering capacity against the influence of acid mine drainage and other more common sources of pollution. -

Freshwater Fisheries Monthly Report – November 2020

Freshwater Fisheries Monthly Report – November 2020 Stock Assessment North Branch Potomac River - Conducted fry counts on the North Branch Potomac River to confirm natural reproduction of rainbow trout in the special zero creel limit management area. Counts were conducted at four locations within the management area - no trout fry were observed. Upper Potomac River - The annual fall electrofishing boat surveys for gamefish were completed on the upper Potomac River. Unfortunately, adult smallmouth bass densities were below average levels. Poor juvenile recruitment in recent consecutive years is a major factor behind these results. Juvenile smallmouth stocking efforts for the middle and lower sections of the river are planned for next year. Walleye and muskellunge were also collected in the surveys. Invasive flathead catfish were found at multiple sites downstream from Dam 5, with the largest measuring 35 inches. Triadelphia Reservoir - Completed the biennial fall electrofishing survey of Triadelphia Reservoir (Howard and Montgomery counties) with assistance from the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC) staff. The survey was conducted on consecutive nights in early November. Large densities of juvenile and early-adult largemouth bass were collected. Additional species observed included northern pike, tiger muskellunge, and smallmouth bass. Federal Aid Reports - Completed final editing of reports for Youghiogheny River Trout Population Monitoring Study; Hoyes Run Trout Population Monitoring Study; and Savage River Tailwater Trout Population Study. Staff also compiled and summarized coldwater data for Zippin depletion and quantitative surveys. Habitat and Water Quality Environmental Review - Provided aquatic resource information for the following environmental review projects: ● Time of year waiver request for a culvert cleaning project at the location of Borden Yard Road in Mount Savage, MD. -

Eastern Continental Divide Loop

Potomac Heritage Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail Garrett County, Maryland Somerset County, Pennsylvania TIMOTHY JACOBSEN–GARRETT COUNTY CHAMBER OF COMMERCE Explore the Eastern Continental Divide Loop Do the Loop! On foot, by kayak, raft and bicycle Places to explore State parks and forests and the Youghiogheny Western Maryland and Hike or backpack to the Savage Wild and Scenic River provide exceptional southwestern Pennsylvania River. That’s the Loop! access to water, trails, scenic vistas and, due to feature exceptional access to various micro-climates, an impressive diversity of flora and fauna. public lands, rivers, streams, The approximately reservoirs, trails, and state parks 150-mile Eastern The Youghiogheny Scenic creating the ultimate outdoor Continental and Wild River, managed recreation experience. Divide Loop to protect the exceptional is a portal range of natural, cultural Paddle the quiet Savage River to explore and outdoor recreational Reservoir. Hike the scenic Monroe unique resources, cuts a Run and Meadow Mountain trails. habitats, northward path through Bicycle along Deep Creek Lake communities some of the most rugged topography in the region. to the Youghiogheny River. and historical TIMOTHY JACOBSEN–GARRETT COUNTY CHAMBER OF COMMERCE Fish a section of river, and landmarks, Deep Creek Lake State Park, raft the exciting Class IV/V connecting the includes a challenging section to Friendsville, area’s most scenic network of mountain biking TIMOTHY JACOBSEN–GARRETT COUNTY Maryland. Paddle to viewpoints through CHAMBER OF COMMERCE trails and a well-marked trail Confluence, Pennsylvania, a continuous network system includes a hike to a lookout and bike on the Great of trails, waterways, and routes tower with exceptional views of western Allegheny Passage and local while traversing the Allegheny Maryland. -

Law Enforcement Officers of the State of Maryland Authorized to Issue Citat

JOHN P. MORRISSEY DISTRICT COURT OF MARYLAND 580 Taylor Avenue Chief Judge Suite A-3 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 Tel: (410) 260-1525 Fax: (410) 974-5026 December 29, 2017 TO: All Law Enforcement Officers of the State of Maryland Authorized to Issue Citations for Violations of the Natural Resources Laws The attached list is a fine or penalty deposit schedule for certain violations of the Natural Resources laws. The amounts set out on this schedule are to be inserted by you in the appropriate space on the citation. The defendant in such cases, who does not care to contest guilt, may prepay the fine in that amount. The fine schedule is applicable whether the charge is made by citation, a statement of charges, or by way of criminal information. For some violations, a defendant must stand trial and is not permitted to prepay a fine or penalty deposit. Additionally, there may be some offenses for which there is no fine listed. In both cases you should check the box which indicates that the defendant must appear in court on the offense. I understand that this fine schedule has been approved for legal sufficiency by the Office of the Attorney General, Department of Natural Resources. This schedule has, therefore, been adopted pursuant to the authority vested in the Chief Judge of the District Court by the Constitution and laws of the State of Maryland. It is effective January 1, 2018, replacing all schedules issued prior hereto, and is to remain in force and effect until amended or repealed. No law enforcement officer in the State is authorized to deviate from this schedule in any case in which he or she is involved. -

Pocket Guide (PDF)

(includes the Youghiogheny River Lake and SEASONS, SIZES, AND CREEL LIMITS – Except for trout season, COMMONWEALTH INLAND WATERS-2021 does not include special regulation areas) which begins at 8 a.m., all regulatory periods in the fishing regulations PENNSYLVANIA are based on the calendar day, one of which ends at midnight and the 2021 Mentored Youth Trout Day: FISHING LICENSE Species Seasons Daily Limit Minimum Size next of which begins immediately thereafter. March 27 (statewide) ** Except those species in waters listed in the Brood Stock Take part in the Commission’s Mentored Youth Trout Day. Youth under BUTTON ALL SPECIES OF TROUT Statewide Opening Day of Trout Season 5 (combined species) 7 inches Lakes Program. Tiger Muskellunge is a muskellunge hybrid. Additional regulations may apply - see Trout April 3 at 8 a.m. - Sept. 6 streams, lakes, and ponds *** Unlawful to take, catch, or kill American Shad in the Susquehanna the age of 16 can join a mentor (adult) angler who has a current fishing These annual buttons are available to River and all its tributaries. River Herring (Alewife and Blueback license and trout permit to fish onSaturday, March 27 on stocked trout 2021 all current, adult and youth Pennsylvania Regulations for stream sections that are both Extended Season: Stocked trout waters and all waters downstream Herring) has a closed year-round season with zero daily limit 3 7 inches waters statewide. For more information, visit www.fishandboat.com/ Seasons, Sizes, fishing license customers who possess a valid Stocked Trout Waters and Class A Wild of stocked trout waters. Jan. -

Maryland Guide To

dnr.maryland.gov MARYLAND GUIDE TO 2017 – FISHING 2018 & CRABBING WHAT’S NEW See page 6 Also inside... • License Information • Seasons, Sizes & Limits •Fish Identification • Public Lakes & Ponds • T idal/Non tidal dividing lines •Oysters & Clams NONTIDAL | CHESAPEAKE BAY | COASTAL BAYS | ATLANTIC OCEAN You Are Here So Are We NOT EVERY TOWING SERVICE HAS A FLEET STANDING BY TO BACK UP THEIR PROMISES. We do. TowBoatU.S. has over 600 red boats from coast to coast, so you’re never far from help when you need it. Our Captains are licensed professionals that will get you and your boat underway and where you need to go in no time. CALL OR GO ONLINE NOW TO JOIN FOR JUST $149 ALL YEAR. 1-800-395-2628 BoatUS.com/towing Towing details can be found online at BoatUS.com/towing or by calling. dnr.maryland.gov Photo courtesy Dee Kolobow 38 Courtesy of Sherry Bishop 40 Photo courtesy of Steve Peperak page 24 43 CONTENTS 44 What’s New���������������������������������������������� 6 Put-and-Take Sport Fish State Records Rules Trout Fishing Areas������������������������22–23 & Procedures�����������������������������������������39 DNR Addresses & Phone Numbers���������������������������������� 8 Special Management Areas Blue Crabs���������������������������������������40–41 Trout������������������������������������������24–25 Natural Resource Police Artificial Reefs��������������������������������������42 Information���������������������������������������������� 8 AllSpecies��������������������������������������26 Oyster & Clams�������������������������������������43