Habakkuk: Challenger and Champion of Yahweh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It Is Difficult to Speak About Jeremiah Without Comparing Him to Isaiah. It

751 It is diffi cult to speak about Jeremiah without comparing him to Isaiah. It might be wrong to center everything on the differences between their reactions to God’s call, namely, Isaiah’s enthusiasm (Is 6:8) as opposed to Jeremiah’s fear (Jer 1:6). It might have been only a question of their different temperaments. Their respec- tive vocation and mission should be complementary, both in terms of what refers to their lives and writings and to the infl uence that both of them were going to exercise among believers. Isaiah is the prophecy while Jeremiah is the prophet. The two faces of prophet- ism complement each other and they are both equally necessary to reorient history. Isaiah represents the message to which people will always need to refer in order to reaffi rm their faith. Jeremiah is the ever present example of the suffering of human beings when God bursts into their lives. There is no room, therefore, for a sentimental view of a young, peaceful and defenseless Jeremiah who suffered in silence from the wickedness of his persecu- tors. There were hints of violence in the prophet (11:20-23). In spite of the fact that he passed into history because of his own sufferings, Jeremiah was not always the victim of the calamities that he had announced. In his fi rst announcement, Jeremiah said that God had given him authority to uproot and to destroy, to build and to plant, specifying that the mission that had been entrusted to him encompassed not only his small country but “the nations.” The magnitude to such a task assigned to a man without credentials might surprise us; yet it is where the fi nger of God does appear. -

![{PDF EPUB} World English Bible-Book of Habakkuk by Zhingoora Books World English Bible-Book of Habakkuk [Books, Zhingoora] on Amazon.Com](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8620/pdf-epub-world-english-bible-book-of-habakkuk-by-zhingoora-books-world-english-bible-book-of-habakkuk-books-zhingoora-on-amazon-com-298620.webp)

{PDF EPUB} World English Bible-Book of Habakkuk by Zhingoora Books World English Bible-Book of Habakkuk [Books, Zhingoora] on Amazon.Com

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} World English bible-Book of Habakkuk by Zhingoora Books World English bible-Book of Habakkuk [Books, Zhingoora] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. World English bible-Book of Habakkuk World English Bible-Book of Matthew [Books, Zhingoora] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. World English Bible-Book of Matthew Oct 18, 2001 · The Book of Habakkuk is the eighth book of the 12 minor prophets of the Bible. It is attributed to the prophet Habakkuk, and was probably composed in the late 7th century BC.. Of the three chapters in the book, the first two are a dialog between Yahweh and the prophet. The message that "the just shall live by his faith" plays an important role in Christian thought. Who Wrote the Book of Habakkuk? The Book of Habakkuk was written by Habakkuk between 612 and 588 BC. This text would have been written around the same time or the span of time that Daniel was taken into captivity by Babylon in 605 BC. In 597 BC Ezekiel … Sep 23, 2012 · Read "World English Bible- Book of Nehemiah" by Zhingoora Bible Series available from Rakuten Kobo. THE HOLY BIBLE Translated from the Latin Vulgate Diligently Compared with the Hebrew, Greek, and Other Editions in Diver... The Book of Habakkuk. Habakkuk is the only prophet to devote his entire work to the question of the justice of God’s government of the world. In the Bible as a whole, only Job delivers a more pointed challenge to divine rule. Habakkuk’s challenge is set up as a dialogue between the prophet and God, in which Habakkuk’s opening complaint about injustices in Judean society ( 1:2–4) is followed in 1:5–11 … Habakkuk is a contemporary of Jeremiah and writes this book around 610 BC or just after the Northern Kingdom (Israel) had been taken captive by Assyria. -

Micah at a Glance

Scholars Crossing The Owner's Manual File Theological Studies 11-2017 Article 33: Micah at a Glance Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Article 33: Micah at a Glance" (2017). The Owner's Manual File. 13. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Owner's Manual File by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MICAH AT A GLANCE This book records some bad news and good news as predicted by Micah. The bad news is the ten northern tribes of Israel would be captured by the Assyrians and the two southern tribes would suffer the same fate at the hands of the Babylonians. The good news foretold of the Messiah’s birth in Bethlehem and the ultimate establishment of the millennial kingdom of God. BOTTOM LINE INTRODUCTION QUESTION (ASKED 4 B.C.): WHERE IS HE THAT IS BORN KING OF THE JEWS? (MT. 2:2) ANSWER (GIVEN 740 B.C.): “BUT THOU, BETHLEHEM EPHRATAH, THOUGH THOU BE LITTLE AMONG THE THOUSANDS OF JUDAH, YET OUT OF THEE SHALL HE COME FORTH” (Micah 5:2). The author of this book, Micah, was a contemporary with Isaiah. Micah was a country preacher, while Isaiah was a court preacher. -

Unwelcome Words from the Lord: Isaiah's Messages

Word & World Volume XIX, Number 2 Spring 1999 Unwelcome Words from the Lord: Isaiah’s Messages ROLF A. JACOBSON Princeton Theological Seminary Princeton, New Jersey I. THE CUSTOM OF ASKING FOR PROPHETIC WORDS N BOTH ANCIENT ISRAEL AND THE NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES, IT WAS COMMON for prophets to be consulted prior to a momentous decision or event. Often, the king or a representative of the king would inquire of a prophet to find out whether the gods would bless a particular action which the king was considering. A. 1 Samuel 23. In the Old Testament, there are many examples of this phe- nomenon. 1 Sam 23:2-5 describes how David inquired of the Lord to learn whether he should attack the Philistines: Now they told David, “The Philistines are fighting against Keilah, and are rob- bing the threshing floors.” David inquired of the LORD, “Shall I go and attack these Philistines?” The LORD said to David, “Go and attack the Philistines and save Keilah.” But David’s men said to him, “Look, we are afraid here in Judah; how much more then if we go to Keilah against the armies of the Philistines?” Then David inquired of the LORD again. The LORD answered him, “Yes, go ROLF JACOBSON is a Ph.D. candidate in Old Testament at Princeton Theological Seminary. He is associate editor of the Princeton Seminary Bulletin and editorial assistant of Theology Today. Isaiah’s word of the Lord, even a positive word, often received an unwelcome re- ception. God’s promises, then and now, can be unwelcome because they warn against trusting any other promise. -

Exploring Zechariah, Volume 2

EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 VOLUME ZECHARIAH, EXPLORING is second volume of Mark J. Boda’s two-volume set on Zechariah showcases a series of studies tracing the impact of earlier Hebrew Bible traditions on various passages and sections of the book of Zechariah, including 1:7–6:15; 1:1–6 and 7:1–8:23; and 9:1–14:21. e collection of these slightly revised previously published essays leads readers along the argument that Boda has been developing over the past decade. EXPLORING MARK J. BODA is Professor of Old Testament at McMaster Divinity College. He is the author of ten books, including e Book of Zechariah ZECHARIAH, (Eerdmans) and Haggai and Zechariah Research: A Bibliographic Survey (Deo), and editor of seventeen volumes. VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Boda Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-201-0) available at http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx Cover photo: Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com Mark J. Boda Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 ANCIENT NEAR EAST MONOGRAPHS Editors Alan Lenzi Juan Manuel Tebes Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach C. L. Crouch Esther J. Hamori Chistopher B. Hays René Krüger Graciela Gestoso Singer Bruce Wells Number 17 EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah by Mark J. -

5. Jesus Christ-The Key of David (Isaiah 22:15-25)

1 Jesus Christ, the Key of David Isaiah 22:15-25 Introduction: In Isaiah 22, the Lord sent Isaiah to make an announcement to a government official named Shebna, who served Hezekiah, the king of Judah. The news he had for Shebna was not good. Shebna had, apparently, used his position to increase his own wealth and glory, and had usurped authority which did not belong to him. Shebna received the news that he would soon be abruptly removed from his office. Isaiah also announced that another man (named Eliakim) would take his place, who would administer the office faithfully. This new man would be a type of Jesus Christ. Isaiah 22:15-25 I. The fall of self-serving Shebna (vv. 15-19) In verse 15, the Lord sent Isaiah to deliver a message to Shebna, who was the treasurer in the government of Judah. He is also described as being “over the house.” This particular position was first mentioned in the time of Solomon. (Apparently, the office did not exist in the days of King Saul or King David, because it is not mentioned.) Afterward, it became an important office both in the northern and southern kingdoms. 1 Kings 4:1-6; 16:9; 18:3 2 Kings 10:5 The office of the man who was “over the house” of the king of Judah seems to have increased in importance over time, until it was similar to the Egyptian office of vizier. Joseph had been given this incredibly powerful position in the government of Pharaoh. (In fact, this position seems to have been created, for the first time, in Joseph’s day.) Joseph possessed all the power of the Pharaoh. -

Jeremiah and Habakkuk Messages from God

K-2nd Grade Sunday School Lesson 4-4 Jeremiah and Habakkuk Messages from God Define it Jeremiah and Habakkuk Jeremiah 1 & 36, Habakkuk 1 Do it Patience is the hardest thing. Impatience leads to so many other sins. We rush ahead impulsively smack into foolish actions. We say what we should leave unsaid because we can’t wait to calm down or let someone else finish. Impatience is connected to selfishness. We have things we want and we bulldoze others to get to it because we cannot wait! Anyway, God is different and aren’t we glad!? Practice improves patience. If your children are impatient with an inability, help them practice until they are able—all the while teaching that patience is a fine quality to possess. If your children are impatient with waiting for something they anticipate happening, help them find something else to do. Daniel Tiger says, when you wait, you can play, sing, and imagine anything If your children are impatient with other people, remind them of something they cannot do and how they would feel for someone to push them to hurry up! Nobody likes that! Drink it The Lord is not slow in doing what He promised – the way some people understand slowness. But God is being patient with you. He does not want anyone to be lost. He wants everyone to change his heart and life. 2 Peter 3: 9 Say it God is patient. Pray it Dear God, thank You for being patient. Amen. Plan it God loves and blesses us by being patient, giving everyone a chance to choose Him. -

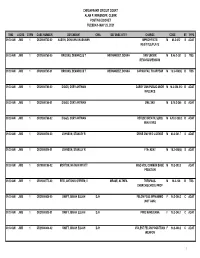

Chesapeake Circuit Court Alan P. Krasnoff, Clerk Posting Docket Tuesday- May 25, 2021

CHESAPEAKE CIRCUIT COURT ALAN P. KRASNOFF, CLERK POSTING DOCKET TUESDAY- MAY 25, 2021 TIME JUDGE CTRM CASE NUMBER DEFENDANT CWA DEFENSE ATTY CHARGE CODE ST TYPE 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000762-00 AUSTIN, DONIVAN VAUSHAWN IMPROP/FICTS M 46.2-612 S ADAT REG/TITLE/PLATE 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000765-00 BROOKS, DEMARCUS T HERNANDEZ, DONNA DRIV UNDER M B.46.2-301 S TBS REVO/SUSPENSION 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000765-01 BROOKS, DEMARCUS T HERNANDEZ, DONNA CAPIAS FAIL TO APPEAR M 18.2-456(6) B TBS 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000766-00 DIGGS, CORY ANTWAN CARRY GUN PUBLIC-UNDR M 18.2-308.012 B ADAT INFLUNCE 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000766-01 DIGGS, CORY ANTWAN DWI, 2ND M B.18.2-266 B ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000766-02 DIGGS, CORY ANTWAN REFUSE BREATH, SUBQ M A.18.2-268.3 B ADAT W/IN 10YRS 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000514-00 JOHNSON, STANLEY R DRIVE CMV W/O LICENSE M 46.2-341.7 S ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000514-01 JOHNSON, STANLEY R FTA- ADAT M 18.2-456(6) S ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR19000796-02 MORTON, NATHAN WYATT MISD VIOL COMMUN BASE M 19.2-303.3 ADAT PRBATION 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000773-00 REID, ANTONIO O'BRIEN; II MEASE, ALTHEA TRESPASS- M 18.2-128 B TBS CHURCH/SCHOOL PROP 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000838-00 SWIFT, ISAIAH ELIJAH DJH FELON POSS WPN/AMMO F 18.2-308.2 C ADAT (NOT GUN) 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000838-01 SWIFT, ISAIAH ELIJAH DJH PWID MARIJUANA F 18.2-248.1 C ADAT 09:30 AM JWB 1 CR21000838-02 SWIFT, ISAIAH ELIJAH DJH VIOLENT FELON POSS/TRAN F 18.2-308.2 C ADAT WEAPON 1 CHESAPEAKE CIRCUIT COURT ALAN P. -

Outline of the Book of Habakkuk

Outline of the Book of Habakkuk The Prophet and Date of Letter The name Habakkuk means “embrace or embracer” (ISBE v. 2, pp. 583). There is absolutely no information about the background or person of Habakkuk recorded. A general date may be determined by readings such as Habakkuk 1:5-11. Jehovah would raise the Babylonians (Chaldeans) to great power. The language appears as though Babylon had already been involved in great warfare, conquering nations, and dreaded as Assyria once was. Nineveh, the great city of Assyria, was conquered by Babylon during the year 612 BC. Babylon’s “rise” to power began at this point. Judah would not feel the actual brunt of Babylon until 605 BC (the year the Egyptians were defeated at Carchemish by Nebuchadnezzar / cf. Jer. 46:2) (cf. Dan. 1:1ff; II Chron. 36:6ff). Though the Lord had pronounced the end of Judah during the days of Manasseh (i.e., 695 – 645 BC) it would not take place for another 40 years. An exact date is impossible to conclude from the facts that are given. The Date of Habakkuk is likely between the fall of Nineveh (i.e., 612 BC) and first attack on Judah (605 BC). Josiah would have been at the end of his good reign as king of Judah (640 to 609 BC.). Judah experienced great peace and achieved many religious reforms under Josiah by the year 621 BC (cf. II Kings 22:1-23:25). Nebuchadnezzar’s determination to put Egypt in subjugation eventually meant taking Judah. Habakkuk, thereby, appears to be a contemporary with Zephaniah, Jeremiah, and possibly Nahum. -

Obadiah Jonah Micah Nahum Habakkuk

OBADIAH JONAH MICAH NAHUM HABAKKUK Assyrian soldiers This lesson examines the books of a vision of Obadiah, but it gives no histori Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, and cal context and no biographical informa Habakkuk, which are part of the Minor tion. The name Obadiah means "servant of Prophets. Yahweh." This name was fairly common in ancient Israel. Thilteen Obadiahs appear in OBADliUI the Old Testament. The Book of Obadiah is primarily a The first of these five books is Obadiah. denunciation of the state of Edom. It It is the shortest book in the Old describes the calamities that the prophet Testament, having only one chapter. We sees befalling the Edomites, who are related know nothing about the prophet Obadiah. to the Israelites. The Edomites traced their The opening verse tells us that the book is lineage back to Esau, the twin brother of BOOKS OF THE BIBLE 110 Jacob. Thus the Edomites and the Israelites JONAH claim the sanle ancestors. Tum now to the Book of Jonah, which Much of the Old Testament expresses a contains a familiar story. The Book of great hostility toward the Edonlites. Psalm Jonah differs from all the other prophetic 137 speaks of the Edomites and declares as books because it is really a narrative about blessed anyone who takes their little ones a prophet and contains almost nothing of and dashes them against the rock. his preaching. Jonah's one proclamation in Why did such harsh feelings exist Jonah 3:4 contains, in Hebrew, only five between Edom and Israel? The answer words. -

An Analysis of Habakkuk 2:1-4 in Conjunction with Romans 1:16-17: the Application for Our Salvation and Daily Living in Jesus Christ

An Analysis of Habakkuk 2:1-4 In Conjunction With Romans 1:16-17: The Application For Our Salvation And Daily Living In Jesus Christ Introduction One of the most powerful statements in Scripture is Romans 1:16-17: “For I am not ashamed of the gospel, for it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes, to the Jew first and also to the Greek. 17 For in it the righteousness of God is revealed from faith to faith; as it is written, ‘But the righteous man shall live by faith.’” However, as we read this passage in the Greek New Testament, when we go to the Hebrew Old Testament, we realize that the HOT quote is worded a bit differently from Paul’s GNT quote: “Behold, as for the proud one, his soul is not right within him; but the righteous will live by his faith” (Habakkuk 2:4). In the GNT Paul simply says, “But the righteous shall live by faith,” whereas Habakkuk 2:4 in the HOT states, “but the righteous will live by his faith.” Why did Paul not quote the passage in the Greek exactly as it is written in the Hebrew? And in addition, what does the phrase, in Romans 1:17 mean, “For in it the righteousness of God is revealed from faith to faith”? These two questions are very important, as they affect every aspect of our lives as believers in Jesus Christ, and we will attempt to answer them in our discussion which follows Influence and Analysis of the Septuagint One very important aspect of Old Testament quotes in the New Testament by Paul is that he predominantly took his quotes from the Greek Septuagint (over fifty times in Romans alone 1), which is the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament. -

Habakkuk Devotionals & Sermon Illustrations

Habakkuk Devotionals & Sermon Illustrations HABAKKUK DEVOTIONALS Our Daily Bread Today in the Word Our Daily Bread Devotionals are Copyrighted by RBC Ministries, Grand Rapids, MI. They are reprinted by permission and all rights are reserved. Today in the Word is copyright by Moody Bible Institute. Used by permission. All rights reserved. HABAKKUK 1 Warren Wiersbe's overview - The name Habakkuk may come from a Hebrew word that means “to embrace.” In his book, he comes to grips with some serious problems and lays hold of God by faith when everything in his life seems to be falling apart. Habakkuk saw the impending Babylonian invasion, and he wondered that God would use a wicked nation to punish His chosen people. His book describes three stages in Habakkuk’s experience—perplexity: faith wavers (chap. 1); perspective: faith watches (chap. 2); and perseverance: faith worships (chap. 3). The key text is Hab 2:4, “But the just shall live by his faith.” It is quoted in Romans 1:17, Galatians 3:11, and Hebrews 10:38. The theme of Romans is “the just” and how to be justified before God. Galatians tells us how the just “shall live,” and the emphasis in Hebrews is on living “by faith.” It takes three New Testament epistles to explain one Old Testament text! - With the Word Habakkuk 1:1-4 The Secret Of Joy Read: Habakkuk 1:1-4; 3:17-19 Though the fig tree may not blossom...yet I will rejoice in the Lord -- Habakkuk 3:17-18 One of the shortest books in the Old Testament is the book of Habakkuk.