Misuse of Prescription Drugs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: a Research-Based Guide (Third Edition)

Publications Revised January 2018 Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (Third Edition) Table of Contents Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (Third Edition) Preface Principles of Effective Treatment Frequently Asked Questions Drug Addiction Treatment in the United States Evidence-Based Approaches to Drug Addiction Treatment Acknowledgments Resources Page 1 Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (Third Edition) The U.S. Government does not endorse or favor any specific commercial product or company. Trade, proprietary, or company names appearing in this publication are used only because they are considered essential in the context of the studies described. Preface Drug addiction is a complex illness. It is characterized by intense and, at times, uncontrollable drug craving, along with compulsive drug seeking and use that persist even in the face of devastating consequences. This update of the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment is intended to address addiction to a wide variety of drugs, including nicotine, alcohol, and illicit and prescription drugs. It is designed to serve as a resource for healthcare providers, family members, and other stakeholders trying to address the myriad problems faced by patients in need of treatment for drug abuse or addiction. Addiction affects multiple brain circuits, including those involved in reward and motivation, learning and memory, and inhibitory control over behavior. That is why addiction is a brain disease. Some individuals are more vulnerable than others to becoming addicted, depending on the interplay between genetic makeup, age of exposure to drugs, and other environmental influences. -

Behavioral Tolerance: Research and Treatment Implications

US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH EDUCATION AND WELFARE • Public Health Service • Alcohol Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration Behavioral Tolerance: Research and Treatment Implications Editor: Norman A. Krasnegor, Ph.D. NIDA Research Monograph 18 January 1978 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration National lnstitute on Drug Abuse Division of Research 5600 Fishers Lane RockviIle. Maryland 20657 For sale by tho Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 (Paper Cover) Stock No. 017-024-00699-8 The NIDA Research Monogroph series iS prepared by the Division of Research of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Its primary objective is to provide critical re- views of research problem areas and techniques. the content of state-of-the-art conferences, integrative research reviews and significant original research its dual publication emphasis iS rapid and targeted dissemination to the scientific and professional community Editorial Advisory Board Avram Goldstein, M.D Addiction Research Foundation Polo Alto California Jerome Jaffe, M.D College Of Physicians and Surgeons Columbia University New York Reese T Jones, M.D Langley Porter Neuropsychitnc Institute University of California San Francisco California William McGlothlin, Ph D Department of Psychology UCLA Los Angeles California Jack Mendelson. M D Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research Center Harvard Medical School McLeon Hospital Belmont Massachusetts Helen Nowlis. Ph.D Office of Drug Education DHEW Washington DC Lee Robins, Ph.D Washington University School of Medicine St Louis Missouri NIDA Research Monograph series Robert DuPont, M.D. DIRECTOR, NIDA William Pollin, M.D. DIRECTOR, DIVISION OF RESEARCH, NIDA Robert C. -

Pharmacology - Neuroadaptation

Pharmacology - Neuroadaptation All drugs of dependence are associated with increased dopamine activity in the so-called reward pathway of the brain-- this pathway that gives us pleasure and tells us what's good for our survival. The overstimulation of the reward system when we use drugs of abuse, or develop an addiction, sets in motion a reinforcing pattern that teaches us to repeat the behaviour. Over time, as drug use and addiction continues and develops, the brain adapts to the overwhelming surges in dopamine. And it adapts by producing less dopamine, by reducing the number and activity of the dopamine receptors, and by essentially turning down the volume on the dopamine system. Our brain strives for balance. In some respects, we can conceptualise it as constantly adapting and changing to function in a way that we can act and feel normal, a process called homeostasis. And when we talk about homeostasis occurring in the brain, we use the term neuroadaptation. When we consume a drug, we alter the functioning of our brain. We upset the balance, and as a result, our brain tries to adapt. It tries to minimise the effect of the drug and get back to normal. If we use a drug frequently, then the brain will adapt to try and be in balance when the drug is present. But if we then stop taking the drug, our brain is no longer in balance, and it can take a really long time for the brain to re-adapt. In psychopharmacology, we refer to these processes as drug tolerance and physical drug dependence. -

Biological Components of Substance Abuse and Addiction

Biological Components of Substance Abuse and Addiction September 1993 OTA-BP-BBS-117 NTIS order #PB94-134624 GPO stock #052-003-01350-9 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Mice of Technology Assessment, BioZogicaZ Components of Substance Abuse and Addiction, OTA-BP-BBS-1 17 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government printing Offke, September 1993). II 10[ \cllc h> 111( I Is ( l(l\ c1 Illllclll 1’1 Illllllp ( )Illcc $L1pCrlfl[L’llL! L’11[ of [)(). UIIIC’111.. \lJl[ $[t~[~ \\( )1’ \\ J.hlllg({lll. [)( ?( l~()? ‘~ ~?h ISBN 0-16 -042096-2 Foreword ubstance abuse and addiction are complex phenomena that defy simple explanation or description. A tangled interaction of factors contributes to an individual’s experimentation with, use, and perhaps subsequent abuse of drugs. Regardless of the mix of contributing factors, the actions and effectss exerted by drugs of abuse underlie all substance abuse and addiction. In order to understand substance abuse and addiction it is first necessary to understand how drugs work in the brain, why certain drugs have the potential for being abused, and what, if any, biological differences exist among individuals in their susceptibility to abuse drugs. This background paper is the first of two documents being produced by OTA as part of an assessment of Technologies for Understanding the Root Causes of Substance Abuse and Addiction. The assessment was requested by the House Committee on Government Operations, the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, and the Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources. This background paper describes biological contributing factors to substance abuse and addiction. The second document being produced by this study will discuss the complex interactions of biochemical, physiological, psychological, and sociological factors leading to substance abuse and addiction. -

Pharmacogenomics: the Promise of Personalized Medicine for CNS Disorders

Neuropsychopharmacology REVIEWS (2009) 34, 159–172 & 2009 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0893-133X/09 $30.00 REVIEW ............................................................................................................................................................... www.neuropsychopharmacology.org 159 Pharmacogenomics: The Promise of Personalized Medicine for CNS Disorders Jose de Leon*,1,2,3,4 1 2 Mental Health Research Center, Eastern State Hospital, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA; College of Medicine, 3 4 University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA; College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA; Psychiatry and Neurosciences Research Group (CTS-549), Institute of Neurosciences, Medical School, University of Granada, Granada, Spain This review focuses first on the concept of pharmacogenomics and its related concepts (biomarkers and personalized prescription). Next, the first generation of five DNA pharmacogenomic tests used in the clinical practice of psychiatry is briefly reviewed. Then the possible involvement of these pharmacogenomic tests in the exploration of early clinical proof of mechanism is described by using two of the tests and one example from the pharmaceutical industry (iloperidone clinical trials). The initial attempts to use other microarray tests (measuring RNA expression) as peripheral biomarkers for CNS disorders are briefly described. Then the challenge of taking pharmacogenomic tests (compared to drugs) into clinical practice is explained by focusing on regulatory -

Prescription Drug Abuse See Page 10

Preventing and recognizing prescription drug abuse See page 10. from the director: The nonmedical use and abuse of prescription drugs is a serious public health problem in this country. Although most people take prescription medications responsibly, an estimated 52 million people (20 percent of those aged 12 and Prescription older) have used prescription drugs for nonmedical reasons at least once in their lifetimes. Young people are strongly represented in this group. In fact, the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s (NIDA) Drug Abuse Monitoring the Future (MTF) survey found that about 1 in 12 high school seniors reported past-year nonmedical use of the prescription pain reliever Vicodin in 2010, and 1 in 20 reported abusing OxyContin—making these medications among the most commonly abused drugs by adolescents. The abuse of certain prescription drugs— opioids, central nervous system (CNS) depressants, and stimulants—can lead to a variety of adverse health effects, including addiction. Among those who reported past-year nonmedical use of a prescription drug, nearly 14 percent met criteria for abuse of or dependence on it. The reasons for the high prevalence of prescription drug abuse vary by age, gender, and other factors, but likely include greater availability. What is The number of prescriptions for some of these medications has increased prescription dramatically since the early 1990s (see figures, page 2). Moreover, a consumer culture amenable to “taking a pill for drug abuse? what ails you” and the perception of 1 prescription drugs as less harmful than rescription drug abuse is the use of a medication without illicit drugs are other likely contributors a prescription, in a way other than as prescribed, or for to the problem. -

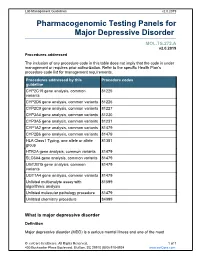

Pharmacogenomic Testing Panels for Major Depressive Disorder

Lab Management Guidelines v2.0.2019 Pharmacogenomic Testing Panels for Major Depressive Disorder MOL.TS.272.A v2.0.2019 Procedures addressed The inclusion of any procedure code in this table does not imply that the code is under management or requires prior authorization. Refer to the specific Health Plan's procedure code list for management requirements. Procedures addressed by this Procedure codes guideline CYP2C19 gene analysis, common 81225 variants CYP2D6 gene analysis, common variants 81226 CYP2C9 gene analysis, common variants 81227 CYP3A4 gene analysis, common variants 81230 CYP3A5 gene analysis, common variants 81231 CYP1A2 gene analysis, common variants 81479 CYP2B6 gene analysis, common variants 81479 HLA Class I Typing, one allele or allele 81381 group HTR2A gene analysis, common variants 81479 SLC6A4 gene analysis, common variants 81479 UGT2B15 gene analysis, common 81479 variants UGT1A4 gene analysis, common variants 81479 Unlisted multianalyte assay with 81599 algorithmic analysis Unlisted molecular pathology procedure 81479 Unlisted chemistry procedure 84999 What is major depressive disorder Definition Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a serious mental illness and one of the most © eviCore healthcare. All Rights Reserved. 1 of 7 400 Buckwalter Place Boulevard, Bluffton, SC 29910 (800) 918-8924 www.eviCore.com Lab Management Guidelines v2.0.2019 common mental disorders in the United States, carrying the heaviest burden of disability among all mental and behavioral disorders. In 2016, roughly 16 million adults in the United States experienced at least one major depression episode in the previous year; this number represented 6.7% of all adults in the United States.1 A major depressive episode can include a number of symptoms, including depressed mood, insomnia or hypersomnia, change in appetite or weight, low energy, poor concentration, and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide, among other symptoms. -

Advances in and Limitations of Up-And-Down Methodology a Pre´Cis of Clinical Use, Study Design, and Dose Estimation in Anesthesia Research Nathan L

Ⅵ REVIEW ARTICLE David C. Warltier, M.D., Ph.D., Editor Anesthesiology 2007; 107:144–52 Copyright © 2007, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Advances in and Limitations of Up-and-down Methodology A Pre´cis of Clinical Use, Study Design, and Dose Estimation in Anesthesia Research Nathan L. Pace, M.D., M.Stat.,* Mario P. Stylianou, Ph.D.† Sequential design methods for binary response variables of the patient can be observed immediately.1 The earliest exist for determination of the concentration or dose associated use by the anesthesia research community of one partic- with the 50% point along the dose–response curve; the up-and- ular sequential design—the up-and-down method down method of Dixon and Mood is now commonly used in anesthesia research. There have been important developments (UDM)—seems to have been in studies of the effective in statistical methods that (1) allow the design of experiments concentration for a 50% response (EC50 or minimum for the measurement of the response at any point (quantile) alveolar concentration) of inhalation anesthestics.2,3 along the dose–response curve, (2) demonstrate the risk of Columb and Lyons4 used the same design and reported certain statistical methods commonly used in literature reports, the EC —labeled by them the minimum local analgesic (3) allow the estimation of the concentration or dose—the tar- 50 get dose—associated with the chosen quantile without the as- concentration (MLAC)—of epidural bupivacaine and li- sumption of the symmetry of the tolerance distribution, and (4) docaine for pain relief during labor. -

Effectiveness and Tolerability of Different Recommended Doses Of

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Effectiveness and Tolerability of Different Recommended Doses of PPIs and H2RAs in GERD: Network Received: 26 April 2016 Accepted: 15 December 2016 Meta-Analysis and GRADE system Published: 19 January 2017 Chao Zhang1, Joey S. W. Kwong2, Rui-Xia Yuan1,3, Hao Chen4, Chang Xu5, Yi-Pin Wang1, Gong-Li Yang6, Jin-Zhu Yan1, Le Peng1, Xian-Tao Zeng1, Hong Weng1, Jie Luo1 & Yu-Ming Niu1,6 Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine-2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) are used for gastro- esophageal reflux disease (GERD); however, the clinical evidence for treatment is poor. We evaluated the effectiveness and tolerability of different doses of PPIs,2 H RAs and placebo in adults with GERD. Six online databases were searched through September 1, 2016. All related articles were included and combined with a Bayesian network meta-analysis from randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The GRADE systems were employed to assess the main outcome. Ninety-eight RCTs were identified, which included 45,964 participants. Our analysis indicated that the full/standard dose of esomeprazole at 40 mg per day was the most efficient in healing among nine different dosages of PPIs and2 H RAs. The main efficacy outcome did not change after adjustments for the area, age, level of disease from endoscopy, year of publication, pharmaceutical industry sponsorship, Intention-to-treat (ITT)/per-protocol (PP), withdrawal rate, pre-set select design bias, single blinded and unblinded studies, study origination in China, study arms that included zero events, inconsistency node or discontinued drug were accounted for in the meta-regressions and sensitivity analyses. -

Novel Pharmacogenomic Markers of Irinotecan-Induced Severe Toxicity in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients

Novel pharmacogenomic markers of irinotecan-induced severe toxicity in metastatic colorectal cancer patients Thèse Siwen Sylvialin Chen Doctorat en sciences pharmaceutiques Philosophiae doctor (Ph.D.) Québec, Canada © Siwen Sylvialin Chen, 2015 ii Résumé L’irinotécan est un agent de chimiothérapie largement utilisé pour le traitement de tumeurs solides, particulièrement pour le cancer colorectal métastatique (mCRC). Fréquemment, le traitement par l’irinotécan conduit à la neutropénie et la diarrhée, des effets secondaires sévères qui peuvent limiter la poursuite du traitement et la qualité de vie des patients. Plusieurs études pharmacogénomiques ont évalué les risques associés à la chimiothérapie à base d’irinotécan, en particulier en lien avec le gène UGT1A, alors que peu d’études ont examiné l’impact des gènes codant pour des transporteurs. Par exemple, le marqueur UGT1A1*28 a été associé à une augmentation de 2 fois du risque de neutropénie, mais ce marqueur ne permet pas de prédire la toxicité gastrointestinale ou l’issue clinique. L’objectif de cette étude était de découvrir de nouveaux marqueurs génétiques associés au risque de toxicité induite par l’irinotécan, en utilisant une stratégie d’haplotype/SNP-étiquette permettant de maximiser la couverture des loci génétiques ciblés. Nous avons analysé les associations génétiques des loci UGT1 et sept gènes codants pour des transporteurs ABC impliqués dans la pharmacocinétique de l’irinotécan, soient ABCB1, ABCC1, ABCC2, ABCC5, ABCG1, ABCG2 ainsi que SLCO1B1. Les profils de 167 patients canadiens atteints de mCRC sous traitement FOLFIRI (à base d’irinotécan) ont été examinés et les marqueurs significatifs ont par la suite été validés dans une cohorte indépendante de 250 patients italiens. -

Alarmone Ap4a Is Elevated by Aminoglycoside Antibiotics and Enhances Their Bactericidal Activity

Alarmone Ap4A is elevated by aminoglycoside antibiotics and enhances their bactericidal activity Xia Jia, Jin Zoua,1, Haibo Penga,1, Anne-Sophie Stolleb, Ruiqiang Xiea, Hongjie Zhanga, Bo Pengc,d, John J. Mekalanosb,2, and Jun Zhenga,e,2 aFaculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, Macau SAR, China; bDepartment of Microbiology and Immunobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; cSchool of Life Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510006, China; dLaboratory for Marine Biology and Biotechnology, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266071, China; and eInstitute of Translational Medicine, University of Macau, Macau SAR, China Contributed by John J. Mekalanos, February 25, 2019 (sent for review December 27, 2018; reviewed by James J. Collins and Colin Manoil) Second messenger molecules play important roles in the responses bactericidal aminoglycosides actually cause cell death but clearly to various stimuli that can determine a cell’s fate under stress multiple pathways are involved. conditions. Here, we report that lethal concentrations of amino- One positive characteristic of aminoglycosides is that they retain glycoside antibiotics result in the production of a dinucleotide good activity against many multidrug-resistant bacteria, such as alarmone metabolite–diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A), which Acinetobacter spp.andPseudomonas aeruginosa (2). However, the promotes bacterial cell killing by this class of antibiotics. We show clinical usage of aminoglycosides has been limited due to their that the treatment of Escherichia coli with lethal concentrations of nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity at higher dosages (12, 13), which can kanamycin (Kan) dramatically increases the production of Ap4A. This induce extended cortical necrosis and overt renal dysfunction (14) elevation of Ap4A is dependent on the production of a hydroxyl as well as permanent hearing loss or balance disorders (2). -

Dopamine Receptor Antagonists Fail to Prevent Induction of Cocaine Sensitization Francis J

Dopamine Receptor Antagonists Fail to Prevent Induction of Cocaine Sensitization Francis J. White, Ph.D., Amit Joshi, M.D., Timothy E. Koeltzow, B.A., and Xiu-Ti Hu, M.D., Ph.D. We investigated the ability of dopamine D1 and D2 class nucleus accumbens neurons. Co-administration of receptor antagonists to prevent the induction of behavioral eticlopride and SCH 23390 also failed to prevent the sensitization to cocaine. The D2 receptor antagonist induction of cocaine sensitization. SCH 23390, but not eticlopride failed to prevent the induction of cocaine eticlopride, prevented the expression of cocaine sensitization. An intermediate dose of the D1 receptor sensitization. We conclude that dopamine receptors are antagonist SCH 23390 (0.1 mg/kg) appeared to prevent the either not involved in the induction of cocaine sensitization induction of cocaine sensitization when tested after 3 days or that redundant mechanisms exist to produce the same of withdrawal, but sensitization was clearly evident after 10 neuroadaptations. [Neuropsychopharmacology 18:26– days of withdrawal. High doses of SCH 23390 alone 40, 1998] © 1998 American College of produced supersensitivity to the behavioral effects of cocaine Neuropsychopharmacology. Published by Elsevier and to the inhibitory effects of D1 receptor agonists on Science Inc. KEY WORDS: Cocaine; Behavioral sensitization; Dopamine responsible for removal of monoamine neurotransmit- D1 receptors; Dopamine D2 receptors; Nucleus accumbens; ters from synapses (Ritz et al. 1987), it is not surprising Ventral tegmental area that the neural systems impacted by these messengers Repeated administration of cocaine produces sensitiza- have been scrutinized for mechanisms of behavioral tion (reverse-tolerance) to its locomotor stimulant ef- sensitization.