Ask the Health & Genetics Committee: Hemangiosarcoma FAQ's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Water Spaniel

V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 1 American Water Spaniel Breed: American Water Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: United States First recognized by the AKC: 1940 Purpose:This spaniel was an all-around hunting dog, bred to retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground with relative ease. Parent club website: www.americanwaterspanielclub.org Nutritional recommendations: A true Medium-sized hunter and companion, so attention to healthy skin and heart are important. Visit www.royalcanin.us for recommendations for healthy American Water Spaniels. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 2 Brittany Breed: Brittany Group: Sporting Origin: France (Brittany province) First recognized by the AKC: 1934 Purpose:This spaniel was bred to assist hunters by point- ing and retrieving. He also makes a fine companion. Parent club website: www.clubs.akc.org/brit Nutritional recommendations: Visit www.royalcanin.us for innovative recommendations for your Medium- sized Brittany. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 4 Chesapeake Bay Retriever Breed: Chesapeake Bay Retriever Group: Sporting Origin: Mid-Atlantic United States First recognized by the AKC: 1886 Purpose:This American breed was designed to retrieve waterfowl in adverse weather and rough water. Parent club website: www.amchessieclub.org Nutritional recommendation: Keeping a lean body condition, strong bones and joints, and a keen eye are important nutritional factors for this avid retriever. Visit www.royalcanin.us for the most innovative nutritional recommendations for the different life stages of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 5 Clumber Spaniel Breed: Clumber Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: France First recognized by the AKC: 1878 Purpose:This spaniel was bred for hunting quietly in rough and adverse weather. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

The Pet Buyer's Guide to Finding a Golden Retriever

The Pet Buyer’s Guide to Finding a Golden Retriever By Cheryl Minnier Your Search Begins… The Golden Retriever is the 2nd most popular breed according to the American Kennel Club. That means that everyday people begin their search for a Golden Retriever who can become a healthy, stable member of their family. However, finding that puppy is not as easy as it once was. The days of opening the newspaper or stopping at a roadside sign and finding the dog of your dreams are long past. This article can help you make more informed decisions about finding a puppy. Today several problems plague our canine friends and any breed that reaches a certain level of popularity will face many challenges. Whenever it appears that there is money to be made breeding dogs, there will be people who will do it without the knowledge, skill and dedication that it takes to produce quality dogs. This can lead to puppies being born that have physical and/or temperament problems that make them unsuitable for family companionship. It can also lead to poor placement of puppies that results in adult dogs needing new homes. To maximize your chances of finding a wonderful companion, it is recommended that you purchase a puppy from a responsible breeder or consider an adult rescue dog. Problems, What Problems? .… Goldens should be healthy, stable dogs but unfortunately there are several problems that can occur. Among them are: Canine Hip Dysplasia (CHD) and Elbow Dysplasia (ED) CHD is a malformation of the hip joint that can cause pain and lameness. -

Ranked by Temperament

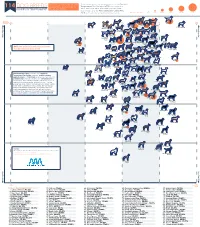

Comparing Temperament and Breed temperament was determined using the American 114 DOG BREEDS Popularity in Dog Breeds in Temperament Test Society's (ATTS) cumulative test RANKED BY TEMPERAMENT the United States result data since 1977, and breed popularity was determined using the American Kennel Club's (AKC) 2018 ranking based on total breed registrations. Number Tested <201 201-400 401-600 601-800 801-1000 >1000 American Kennel Club 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 1. Labrador 100% Popularity Passed 2. German Retriever Passed Shepherd 3. Mixed Breed 7. Beagle Dog 4. Golden Retriever More Popular 8. Poodle 11. Rottweiler 5. French Bulldog 6. Bulldog (Miniature)10. Poodle (Toy) 15. Dachshund (all varieties) 9. Poodle (Standard) 17. Siberian 16. Pembroke 13. Yorkshire 14. Boxer 18. Australian Terrier Husky Welsh Corgi Shepherd More Popular 12. German Shorthaired 21. Cavalier King Pointer Charles Spaniel 29. English 28. Brittany 20. Doberman Spaniel 22. Miniature Pinscher 19. Great Dane Springer Spaniel 24. Boston 27. Shetland Schnauzer Terrier Sheepdog NOTE: We excluded breeds that had fewer 25. Bernese 30. Pug Mountain Dog 33. English than 30 individual dogs tested. 23. Shih Tzu 38. Weimaraner 32. Cocker 35. Cane Corso Cocker Spaniel Spaniel 26. Pomeranian 31. Mastiff 36. Chihuahua 34. Vizsla 40. Basset Hound 37. Border Collie 41. Newfoundland 46. Bichon 39. Collie Frise 42. Rhodesian 44. Belgian 47. Akita Ridgeback Malinois 49. Bloodhound 48. Saint Bernard 45. Chesapeake 51. Bullmastiff Bay Retriever 43. West Highland White Terrier 50. Portuguese 54. Australian Water Dog Cattle Dog 56. Scottish 53. Papillon Terrier 52. Soft Coated 55. Dalmatian Wheaten Terrier 57. -

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally Active and Alert, Sporting Dogs Make Likeable, Well-Rounded Companions

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally active and alert, Sporting dogs make likeable, well-rounded companions. Remarkable for their instincts in water and woods, many of these breeds actively continue to participate in hunting and other field activities. Potential owners of Sporting dogs need to realize that most require regular, invigorating exercise. The breeds of the AKC Sporting Group were all developed to assist hunters of feathered game. These “sporting dogs” (also referred to as gundogs or bird dogs) are subdivided by function—that is, how they hunt. They are spaniels, pointers, setters, retrievers, and the European utility breeds. Of these, spaniels are generally considered the oldest. Early authorities divided the spaniels not by breed but by type: either water spaniels or land spaniels. The land spaniels came to be subdivided by size. The larger types were the “springing spaniel” and the “field spaniel,” and the smaller, which specialized on flushing woodcock, was known as a “cocking spaniel.” ~~How many breeds are in this group? 31~~ 1. American Water Spaniel a. Country of origin: USA (lake country of the upper Midwest) b. Original purpose: retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground c. Other Names: N/A d. Very Brief History: European immigrants who settled near the great lakes depended on the region’s plentiful waterfowl for sustenance. The Irish Water Spaniel, the Curly-Coated Retriever, and the now extinct English Water Spaniel have been mentioned in histories as possible component breeds. e. Coat color/type: solid liver, brown or dark chocolate. A little white on toes and chest is permissible. -

Chapter 2 MILITARY WORKING DOG HISTORY

Military Working Dog History Chapter 2 MILITARY WORKING DOG HISTORY NOLAN A. WATSON, MLA* INTRODUCTION COLONIAL AMERICA AND THE CIVIL WAR WORLD WAR I WORLD WAR II KOREAN WAR AND THE EARLY COLD WAR VIETNAM WAR THE MILITARY WORKING DOG CONCLUSION *Army Medical Department (AMEDD) Regimental Historian; AMEDD Center of History and Heritage, Medical Command, 2748 Worth Road, Suite 28, Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston, Texas 78234; formerly, Branch Historian, Military Police Corps, US Army Military Police School, Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri 83 Military Veterinary Services INTRODUCTION History books recount stories of dogs accompany- which grew and changed with subsequent US wars. ing ancient armies, serving as sources of companion- Currently, US forces utilize military working dogs ship and performing valuable sentry duties. Dogs also (MWDs) in a variety of professions such as security, fought in battle alongside their owners. Over time, law enforcement, combat tracking, and detection (ie, however, the role of canines as war dogs diminished, for explosives and narcotics). Considered an essential especially after firearms became part of commanders’ team member, an MWD was even included in the arsenals. By the 1800s and up until the early 1900s, the successful raid against Osama Bin Laden in 2011.1 (See horse rose to prominence as the most important mili- also Chapter 3, Military Working Dog Procurement, tary animal; at this time, barring some guard duties, Veterinary Care, and Behavioral Services for more dogs were relegated mostly to the role of mascots. It information about the historic transformation of the was not until World War II that the US Army adopted MWD program and the military services available broader roles for its canine service members—uses for canines.) COLONIAL AMERICA AND THE CIVIL WAR Early American Army dogs were privately owned tary continued throughout the next century and into at first; there was neither a procurement system to the American Civil War. -

National Geographic Magazine Features 'Hero Dogs'

June 2014 Military Working Dog Team Support Association, Inc. Award Winning Monthly Newsletter MWDTSA KENNEL TALK Volume 6, Issue 6 www.mwdtsa.org Support MWDTSA now and you won’t miss any of the photos, stories, news and highlights of 2014! Kennel Talk is an award winning MWD publication! Inside this issue: National Geographic — 1 Hero Dogs MWDTSA Virtual World 4 Tour - Buckley AFB Gone Fishin’ Care 6 Package Event PAWS for Reading 8 The Baddy Visit 9 From the Archives 10 The June, 2014 issue of National Geographic magazine features Hero Dogs on its front cover. National Geographic magazine has graciously permitted us to repro- What skills can you share duce an excerpt of the lead article ‘The Dogs of War’, as well as use some of to support our dog teams? their stunning photos by first-time National Geographic photographer, Adam We are looking for volun- Ferguson. teers in: Graphic courtesy of National Geographic magazine. Fundraising Grant writing Giving presentations Soliciting in kind - National Geographic Magazine donations Newsletter editing Features ‘Hero Dogs’ Social networking By Avril Roy-Smith Contact us for more info: There can be no doubt that there are few mag- publication chooses its cover photo and feature azines in the world as old and prestigious as article for an issue, always including in-depth [email protected] the National Geographic magazine. When that information, personal stories and a breathtak- National Geographic continued page 2 P a g e 2 MWDTSA KENNEL TALK J u n e 2 0 1 4 www.mwdtsa.org National Geographic continued from page 1 ing selection of photographs, it brings the attention of the world The issue is truly an exploration and celebration of MWDs and to that story. -

How to Contact NORCAL Golden Retriever Rescue

NORCAL Golden Retriever A nonprofit, volunteer organization dedicated to finding new homes for displaced Golden Retrievers in Northern California Rescue Volume VII, Issue No. 3 ~ Winter 2001 9th Annual Auction, Raffle Big Success By Dave Berry GRR’s Ninth Annual Auction and Wine Tast N ing took place on October 27th, 2001 at the Palo Alto Elks Lodge. Over 375 attendees enjoyed an array of appetizers coordinated by Carol Porter and many helpers, along with an incredible selection of world-class wines donated by Paul Bullard and Laurie Tobias. Wines which would grace the top of the list at most restaurants were served for the “regular” offerings, and guests were also treated to special tastings of the likes of Marcassin and Littorai Chardonnays, Will- iams Selyem Pinot Noir, and the elusive Plumpjack Reserve Continued on page 2 In This Issue Auction & Raffle . 1-5 Charlie’s Knees. .6-7 Golden Galleria . 9-13 In Memoriam . .14 * Rescued to Rescuer . 15 Parade of Rescue goldens . 17 NORCAL Golden Retriever Rescue, Inc. Founder: Dorothy Carter President: Dave Berry Mailing Address: 405 El Camino Real, Suite 420 Menlo Park, CA 94025-5240 Purpose: NORCAL Golden Retriever Rescue, Inc. (NGRR) is a nonprofit, volunteer organization dedicated to the rescue, rehabilitation, and placement of displaced Golden Retrievers in Northern California. Volunteers: NGRR has a large network of volunteers in communities throughout Northern California. Among these are a board of directors and numerous area coordinators and foster families who care for and place over 400 Goldens a year into new homes. Our volunteers do not receive any form of compensation for their time and effort. -

The Golden Retriever: an Illustrated Guide to the Breed

The Golden Retriever: An Illustrated Guide to the Breed ® Golden Retriever Club of America © Golden Retriever Club of America 2015 ® The Judges' Education Committee of the GRCA has various materials available for those wishing to further their understanding of the Golden Retriever. Consult www.grca.org for additional information. Some of these materials include: DVD: The Golden Retriever, produced by Rachel Page Elliott for GRCA. Consult www.grca.org for order information. Video/DVD: The Golden Retriever, produced by AKC 1991. 20 min. May be purchased from the American Kennel Club. Booklet: A Study of the Golden Retriever. By Marcia R Schlehr.1994 edition; Softcover; 64 pages, dozens of illustrations, concise text covering all aspects of structure, movement, breed type and character for exhibitors, breeders, and judges. Consult www.grca.org for order information. Booklet: An Introduction to the Golden Retriever, 75 page booklet produced by the GRCA General information about the breed, not specifically for judges. $5.00. It has a bibliography of books on the breed, addresses for further information. Consult www.grca.org for order information. © GRCA 2010-2015, with material by Marcia R. Schlehr, originally published in The Golden Retriever: a Seminar for Judges ©1995, 2005 and used with her permission. © All drawings by Marcia R. Schlehr, P.O. Box 515, .Clinton M1 49236. Photo Credits: John Ashbey, Louise Battley, Carolina Bibiloni, Bev Brown, Christopher Butler, Jim Cohen, Donna Cutler, Dean Dennis Photography, Doug Field, Mick Gast, JC Photography, Gloria Kerr, Flynn Lamont, Barbara Loree, Ree Maple, Chris Miele, Ainslie Mills, Suzi Rezy, Liz Russell, June Smith, Steve Southard, Sandy Tatham, Caron To, Berna Welch, Scottie Westfall III, American Kennel Club, GRCA Archives. -

Puppy Packet

Labrador Retrievers Inc. Today the Labrador is the second most popular breed in the United States. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE You may be interested in the Labrador LABRADOR RETRIEVER Retriever for many reasons – a family pet, a hunting companion, a field trial competitor, Introduction obedience training, or a show dog. Whatever your intentions, the dog requires the same It is against the policy of the Labrador conformation and physical condition. Retriever Club Inc. to recommend specific Whatever your objective, only you – the breeders, stud dogs or kennels. Accordingly, owner – through affection, care and training the club records do not contain information can enable the Labrador to fulfill its potential. regarding members providing stud services, or having puppies for sale. Choosing a Reputable Breeder Because of your interest, we have prepared this brochure to better acquaint you The first step in acquiring a Labrador with the characteristics of the breed, and to Retriever puppy is selecting a reputable assist you in the selection of a puppy or breeder. Buying a dog is much akin to breeder, or stud service. purchasing a diamond; if you are not yourself It is our sincere wish that the following an expert, you must rely upon the knowledge information will prove helpful. and integrity of the seller. The options open to you as a buyer are as follows: History 1. Pet Shop or Animal Dealer: In our The Labrador Retriever first made its opinion, this is the worst possible place to appearance at English maritime towns that buy a dog. Hardly a week goes by that we do were engaged in the fishing industry with not hear “horror stories” from unsuspecting Newfoundland. -

Domestic Dogs of the Ancient South Pacific

Annual Research & Review in Biology 25(2): 1-11, 2018; Article no.ARRB.40377 ISSN: 2347-565X, NLM ID: 101632869 What We Have Lost: Domestic Dogs of the Ancient South Pacific Carys Louisa Williams1, Silvia Michela Mazzola2*, Giulio Curone2 and Giovanni Quintavalle Pastorino2,3 1Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regents Park, London, NW1 4RY, United Kingdom. 2Department of Veterinary Medicine, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy. 3Faculty of Life Sciences, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PT, United Kingdom. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Author CLW designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors SMM and GQP managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/ARRB/2018/40377 Editor(s): (1) George Perry, Dean and Professor of Biology, University of Texas at San Antonio, USA. Reviewers: (1) Robin Cook, South Africa. (2) Tamer Çağlayan, Selcuk University, Turkey. (3) El Mahdy Cristina, University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca, România. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/23786 Received 7th January 2018 Accepted 19th March 2018 Review Article rd Published 23 March 2018 ABSTRACT In the thousands of years that followed dog domestication, wherever humans went, dogs surely followed. However, the tale of the dog in the ancient South Pacific is often an overlooked one. A small, bandy-legged dog, seemingly not much use for anything but food, this canine could easily be overshadowed in history by more accomplished breeds; the sled dogs of Siberia, the sight hounds of the Middle East, the herders and guarders of Europe, or the practical retrievers of North America. -

Aging Dog Care

Homeward Bound Golden Retriever Rescue Golden Rule Dog Training How to Care for Your Aging Dog Whether your dog has been your loving companion for a long time or you have rescued an older dog, he is slowing down and his needs are changing. He will depend on you more than ever to keep him healthy and comfortable. Depending on your dogs breed and size, most dogs reach "old age" at about seven years. Older dogs still have a lot of life in them, but their bodies and minds are changing just as aging humans do as we age. Their metabolism and immune systems slow down, and arthritis may affect their ability to move around as they once did. Your dog’s vision and hearing may also become impaired as part of the natural aging process. You may also notice changes in your dog's appearance and disposition. The fur around his muzzle and eyebrows may turn gray (we call this sugar-face)! He may be less active and less eager to play and he may become irritable around children and/or other dogs. Your older dog should be examined by your veterinarian at least once a year. Some vets even recommend a checkup every six months depending on general health. Vets can perform special procedures to identify age-related problems. Blood tests can be taken to check the liver, kidneys and pancreas; an electrocardiogram can detect signs of heart disease; other tests can check vision and hearing. Your vet can also give you advice on how to make life more comfortable for your old friend.