FALL 2020 Volume 7 Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC JOURNEY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI TO BRAZIL ON THE OCCASION OF THE FIFTH GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE BISHOPS OF LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN INAUGURAL SESSION OF THE FIFTH GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE BISHOPS OF LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI Conference Hall, Shrine of Aparecida Sunday, 13 May 2007 Dear Brother Bishops, beloved priests, religious men and women and laypeople, Dear observers from other religious confessions: It gives me great joy to be here today with you to inaugurate the Fifth General Conference of the Bishops of Latin America and the Caribbean, which is being held close to the Shrine of Our Lady of Aparecida, Patroness of Brazil. I would like to begin with words of thanksgiving and praise to God for the great gift of the Christian faith to the peoples of this Continent. Likewise, I am most grateful for the kind words of Cardinal Francisco Javier Errázuriz Ossa, Archbishop of Santiago and President of CELAM, spoken in his own name, on behalf of the other two Presidents and for all the participants in this General Conference. 1. The Christian faith in Latin America Faith in God has animated the life and culture of these nations for more than five centuries. From the encounter between that faith and the indigenous peoples, there has emerged the rich Christian culture of this Continent, expressed in art, music, literature, and above all, in the religious traditions and in the peoples’ whole way of being, united as they are by a shared history and a 2 shared creed that give rise to a great underlying harmony, despite the diversity of cultures and languages. -

Plenary Indulgence

Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers Pope Francis Proclaims Plenary Indulgence Affirming the Response to the PAENITENIARIA 10th Year Jubilee Plenary Indulgence Honoring Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers, by Apostolic Papal Decree a Plenary Indulgence is granted to faithful making pilgrimage to Lourdes or experiencing Lourdes in a Virtual Pilgrimage with North American Lourdes Volunteers by fulfilling the usual norms and conditions between July 16, 2013 thru July 15, 2020. APOSTOLICA Jesus Christ lovingly sacrificed Himself for the salvation of humanity. Through Baptism, we are freed from the Original Sin of disobedience inherited from Adam and Eve. With our gift of free will we can choose to sin, personally separating ourselves from God. Although we can be completely forgiven, temporal (temporary) consequences of sin remain. Indulgences are special graces that can rid us of temporal punishment. What is a plenary indulgence? “An indulgence is a remission before God of the temporal punishment Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers due to sins whose guilt has already been forgiven.” (CCC 1471) There Public Association of the Christian Faithful and First Hospitality of the Americas are two types of indulgences: plenary and partial. A plenary indulgence www.LourdesVolunteers.org [email protected] removes all of the temporal punishment due to sin; a partial indulgence (315) 476-0026 FAX (419) 730-4540 removes some but not all of the temporal punishment. © 2017 V. 1-18 What is temporal punishment for sin? How can the Church give indulgences? Temporal punishment for sin is the sanctification from attachment to sin, The Church is able to grant indulgences by the purification to holiness needed for us to be able to enter Heaven. -

Total Christ Ecclesiology Introduction: After Modernity, What? Brian

Total Christ Ecclesiology Introduction: After Modernity, What? Brian McLaren: So what does it look like to conceive of a Christianity in another way that’s not modern? “Can you imagine what happens to the church, the whole Christian enterprise, when it has so thoroughly accommodated to modernity – so much so that it has no idea of any way Christianity could exist other than a modern way?1 Thomas Oden: Where did we get the twisted notion that orthodoxy is essentially a set of ideas rather than a living tradition of social experience? Our stereotype of orthodoxy is that of frozen dogma, rather than a warm continuity of human experience--of grandmothers teaching granddaughters, of feasts and stories, of rites and dancing. Orthodoxies are never best judged merely by their doctrinal ideas, but more so by their social products, the quality of their communities... They await being studied sociologically, not just theologically.2 • Post-Modern Yawn: o From modern reductionism(either-or small minded) to post-modern nothingism (anything minded) back to pre-modern? (both-ands?) • The cliché of a “re” prefix: Doug Pagitt’s Church Re-imagined…, Driscoll’s “Reformission…,” Chester and Timms “Reshaping…” etc o As much a protest as it is a search that dares to imagine spirituality and church practice no longer western facing and modernist • Neo-Denominational Unsettledness Lesslie Newbigin, (Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture); It is the common observation of sociologists of religion that denominationalism is the religious aspect of secularization. It is the form that religion takes in a culture controlled by the ideology of the Enlightenment. -

Baptism on Behalf of the Dead”: 1 Corinthians 15:29 in Its Hellenistic Context

ABSTRACT “BAPTISM ON BEHALF OF THE DEAD”: 1 CORINTHIANS 15:29 IN ITS HELLENISTIC CONTEXT by Matthew Michael Connor This thesis analyzes 1 Corinthians 15:29 – a reference to “Baptism on behalf of the dead” – as an ancient Mediterranean ritual conducted on behalf of the dead. Scholars have been unable to reach a consensus regarding what Paul was referring to in this passage, with many commentators rejecting the most simple and obvious reading of the text. This paper analyzes the text and translation of 15:29, as well as the history of its interpretation before turning to the category of rituals on behalf of the dead in the ancient world. With a cultural predisposition toward ritual interaction between the living and the dead established in the ancient Mediterranean world, vicarious baptism in Corinth is approached using hybridity theory, which acknowledges the religious creativity of the Corinthians, standing in the contact zone between Paul’s Jesus cult and this longstanding Greek tradition of ritual actions performed on behalf of the dead. “BAPTISM ON BEHALF OF THE DEAD” 1 CORINTHIANS 15:29 IN ITS HELLENISTIC CONTEXT A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Comparative Religion by Matthew Michael Connor Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2010 Advisor________________________ James Constantine Hanges Reader_________________________ Elizabeth Wilson Reader_________________________ Deborah Lyons Contents Introduction 1 The Text and Its Reception 4 The Hellenistic Context 22 The Importance of Hybridity 41 Conclusion 56 Works Cited 59 ii Introduction The writings of the Apostle Paul, like the rest of the New Testament, are not without their mysteries. -

Study Guide for JOHN OWEN's the MORTIFICATION OF

Study Guide STUDY GUIDE FOR JOHN Owen’s THE MORTIFICATION OF SIN Rob Edwards THE BANNER OF TRUTH TRUST [] THE MORTIFICATION OF SIN THE BANNER OF TRUTH TRUST 3 Murrayfield Road, Edinburgh EH12 6EL, UK PO Box 621, Carlisle, PA 17013, USA * © The Banner of Truth Trust 2008 ISBN-13: 978 0 85151 999 9 * Typeset in 1O.5/14 pt Sabon Oldstyle Figures at The Banner of Truth Trust, Edinburgh. Printed in the USA by VersaPress, Inc., East Peoria, IL. * Scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, copyright © Crossway 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. The page numbers in this Study Guide follow the page numbers in John Owen, The Mortification of Sin, Abridged and Made Easy to Read by Richard Rushing (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 2004) [] Study Guide Preface hile studying The Mortification of Sin by John WOwen there are a couple of things to keep in mind. First, this short book is focused on the doctrine of sanctification, to be distinguished from the doctrine of justification. In justification, the Christian is declared righteous, not because he is, in himself, righteous to any degree, but because of the righteousness of Christ alone. The Apostle Paul says in Romans 8:1 that ‘There is there- fore now no condemnation for those in Christ Jesus.’ This is the foundation on which the Christian begins the struggle against personal sin, which is the focus of sancti- fication. It is in sanctification that God begins tomake the Christian into what he has already declared the Christian to be, righteous. -

Some Insights from John Wesley and ‘The People Called Methodists’

DENOMINATIONAL IDENTITY IN A WORLD OF THEOLOGICAL INDIFFERENTISM: SOME INSIGHTS FROM JOHN WESLEY AND ‘THE PEOPLE CALLED METHODISTS’ David B. McEwan This article has been peer reviewed. This article examines the importance of denominational identity for the early Methodists and its implications for us today. John Wesley clearly believed God had raised up the Methodists to live and proclaim the message of scriptural holiness. The challenge of maintaining the ethos of the Methodist communities required close attention to those critical elements that shaped both their lives and their beliefs. Evidence is presented of Wesley’s commitment to focus on the ‘essentials’ that defined his movement, while leaving room for diversity on ‘non-essentials’ to allow for cooperation in mission between different Christian traditions. Having identified these critical elements in Wesley’s own day, the question is asked how this might be applied today, not only in a local church setting but also for those involved in theological education and ministerial formation. ____________________________________________________ Introduction In the last ten years or so there has been a spate of books, articles, and conferences expressing concern about evangelical identity and denominational identity. Recently the Assemblies of God raised questions about the current importance and practice of speaking in tongues within their movement. Many Reformed denominations are seeking to return to a more robust form of Calvinism and my own denomination (Church of the Nazarene) is concerned about the loss of our Wesleyan heritage, particularly the emphasis on holiness of heart and life. The focus of this paper is not to examine whether the current concerns are valid, nor is it to examine all the possible reasons for this loss of ‘identity.’ Instead, I want to look briefly at one particular concern highlighted by many denominational scholars and leaders— Aldersgate Papers, vol. -

Amillennialism Reconsidered Beatrices

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 43, No. 1,185-210. Copyright 0 2005 Andrews University Press. AMILLENNIALISM RECONSIDERED BEATRICES. NEALL Union College Lincoln, Nebraska Introduction G. K. Beale's latest commentary on Revelation and Kim Riddlebarger's new book A Casefor Ami~~ennialismhave renewed interest in the debate on the nature of the millennium.' Amillennialism has an illustrious history of support from Augustine, theologians of the Calvinistic and ~utheran confessions, and a long line of Reformed theologians such as Abraham Kuyper, Amin Vos, H. Ridderbos, A. A. Hoekema, and M. G. line? Amillennialists recognize that a straightforward reading of the text seems to show "the chronologicalp'ogression of Rev 19-20, the futurity of Satan's imprisonment,the physicality of 'the first resurrection' and the literalness of the one thousand years" (emphasis supplied).) However, they do not accept a chronologicalprogression of the events in these chapters, preferring instead to understand the events as recapitulatory. Their rejection of the natural reading of the text is driven by a hermeneutic of strong inaugurated eschatology4-the paradox that in the Apocalypse divine victory over the dragon and the reign of Christ and his church over this present evil world consist in participating with Christ in his sufferings and death? Inaugurated eschatology emphasizes Jesus' victory over the powers of evil at the cross. Since that monumental event, described so dramatically in Rev 12, Satan has been bound and the saints have been reigning (Rev 20). From the strong connection between the two chapters (see Table 1 below) they infer that Rev 20 recapitulates Rev 12. -

Understanding Sanctification

THEOLOGY & APPLICATION Understanding Sanctification anctification is the work of God within the believer by which we grow into the image of Jesus Christ and display the fruit of the Spirit. The imputed holiness of Christ becomes ours at the moment of our Sconversion. Now in our daily behavior, practical holiness is to be lived out. Models of Sanctification THE TEACHING OF CHRISTIAN PERFECTION John Wesley (1703–91) believed in a state of Christian perfection — a state subsequent to salvation. This teaching of Christian perfection is based on a second blessing being the key to holiness. This second work of God was described as “perfection,” “second blessing,” “holiness,” “perfect love,” or “entire sanctification.” This view is that through a second experience, followers of Jesus enter an upgraded quality of Christian living. Through this second blessing, we sense God’s love more vividly and our own love for God. The heart is cleansed from sin so that sin ceases to control the believer’s behavior. Full and genuine holiness of life (so it is claimed) comes after this second experience, this second work of grace. This “perfection” happens in a single instant when the believer is raised to the higher level of perfection. But this state of perfection can be lost. The believer then falls away and may be eternally lost. THE HOPE OF THE GOSPEL 117 Critique Christian perfection is not a biblical view of sanctification. This view confuses Christian maturity with Christian perfection. In sanctification, we grow in Christian maturity, but we never reach Christian perfection until that eternal day when we see Jesus Christ face to face. -

Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Trends and Issues in Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements" (2009). Trends and Issues in Missions. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trends and Issues in Missions by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pentecostal/Charismatic Movements Page 1 Pentecostal Movement The first two hundred years (100-300 AD) The emphasis on the spiritual gifts was evident in the false movements of Gnosticism and in Montanism. The result of this false emphasis caused the Church to react critically against any who would seek to use the gifts. These groups emphasized the gift of prophecy, however, there is no documentation of any speaking in tongues. Montanus said that “after me there would be no more prophecy, but rather the end of the world” (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Vol II, p. 418). Since his prophecy was not fulfilled, it is obvious that he was a false prophet (Deut . 18:20-22). Because of his stress on new revelations delivered through the medium of unknown utterances or tongues, he said that he was the Comforter, the title of the Holy Spirit (Eusebius, V, XIV). -

Presbyterians and Revival Keith Edward Beebe Whitworth University, [email protected]

Whitworth Digital Commons Whitworth University Theology Faculty Scholarship Theology 5-2000 Touched by the Fire: Presbyterians and Revival Keith Edward Beebe Whitworth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/theologyfaculty Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Beebe, Keith Edward. "Touched by the Fire: Presbyterians and Revival." Theology Matters 6.2 (2000): 1-8. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theology at Whitworth University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Whitworth University. TTheology MMattersatters A Publication of Presbyterians for Faith, Family and Ministry Vol 6 No 2 • Mar/Apr 2000 Touched By The Fire: Presbyterians and Revival By Keith Edward Beebe St. Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland, Undoubtedly, the preceding account might come as a Tuesday, March 30, 1596 surprise to many Presbyterians, as would the assertion that As the Holy Spirit pierces their hearts with razor- such experiences were a familiar part of the spiritual sharp conviction, John Davidson concludes his terrain of our early Scottish ancestors. What may now message, steps down from the pulpit, and quietly seem foreign to the sensibilities and experience of present- returns to his seat. With downcast eyes and heaviness day Presbyterians was an integral part of our early of heart, the assembled leaders silently reflect upon spiritual heritage. Our Presbyterian ancestors were no their lives and ministry. The words they have just strangers to spiritual revival, nor to the unusual heard are true and the magnitude of their sin is phenomena that often accompanied it. -

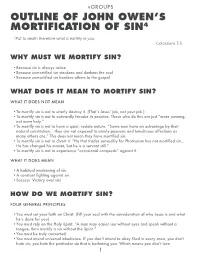

Outline of John Owen's Mortification of Sin4

vGROUPS OUTLINE OF JOHN OWEN’S MORTIFICATION OF SIN4 5Put to death therefore what is earthly in you… Colossians 3:5 WHY MUST WE MORTIFY SIN? • Because sin is always active • Because unmortified sin weakens and darkens the soul • Because unmortified sin hardens others to the gospel WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO MORTIFY SIN? WHAT IT DOES NOT MEAN • To mortify sin is not to utterly destroy it. (That’s Jesus’ job, not your job.) • To mortify sin is not to outwardly forsake its practice. Those who do this are just “more cunning; not more holy.” • To mortify sin is not to have a quiet, sedate nature. “Some men have an advantage by their natural constitution… they are not exposed to unruly passions and tumultuous affections as many others are.” This does not mean they have mortified sin. • To mortify sin is not to divert it. “He that trades sensuality for Pharisaism has not mortified sin… He has changed his master, but he is a servant still.” • To mortify sin is not to experience “occasional conquests” against it. WHAT IT DOES MEAN • A habitual weakening of sin. • A constant fighting against sin. • Success. Victory over sin! HOW DO WE MORTIFY SIN? FOUR GENERAL PRINCIPLES • You must set your faith on Christ. (Fill your soul with the consideration of who Jesus is and what he’s done for you) • You must rely on the Holy Spirit. “A man may easier see without eyes and speak without a tongue, than mortify a sin without the Spirit.” • You must be truly converted. • You must intend universal obedience. -

Do Christians Have a Worldview?

LET GO AND LET GOD? A Survey and Analysis of Keswick Theology ANDREW DAVID NASELLI FOREWORD BY THOMAS R. SCHREINER Copyright © 2010 by Andrew David Naselli This book packs an extraordinary amount of useful summary, critical analysis, and pastoral reflection into short compass. One does not have to agree with every opinion to recognize that this is a comprehensive and penetrating analysis of Keswick theology down to 1920. The book will do the most good, however, if it encourages readers in a more faithful way to pursue that holiness without which we will not see the Lord (Hebrews 12:14). D. A. Carson Research Professor of New Testament Trinity Evangelical Divinity School Deerfield, Illinois For years popular Christian teachers have been telling us the secret key to the victorious, higher, deeper, more abundant Christian life. We’ve been told just to “let go and let God.” If you’ve heard that teaching, you’ll want to read this book—the definitive history and critique of second-blessing theology. You’ll learn not only where this theology went wrong, but will also discover afresh the well-worn old paths of biblical faithfulness and holiness. Andy Naselli is an extraordinarily careful scholar who leaves no stone unturned, but also a compassionate guide who longs to help and serve the church of Jesus Christ. Readers of this work will be instructed and encouraged in their Christian walk. Justin Taylor Vice President of Editorial; Managing editor, ESV Study Bible Crossway Blogger at Between Two Worlds Wheaton, Illinois Keswick theology cast a wide and long shadow over twentieth-century church life in America.