Marketing Communication Trends in Sports Organisations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kits Version

COUNTER ATTACK version 1.4 These representations are 100% unofficial KITS THAT COME WITH THE GAME ENGLAND ITALY SCOTLAND OTHER EUROPEAN TEAMS 021 004 022 118 001 002 040 041 002 SOON... 061 042 003 057 058 119 059 028 006 095 096 099 042 9 7 4 5 8 10 6 2 7 4 6 5 7 3 4 9 3 9 11 2 6 JUVENTUS AJAX YELLOW GK BLUE GK NEWCASTLE ARSENAL WEST HAM BOURNEMOUTH BRIGHTON CHELSEA CRYSTAL PALACE AC MILAN ATALANTA/ BOLOGNA BRESCIA CAGLIARI/ FIORENTINA ABERDEEN CELTIC DUNDEE UTD HAMILTON HEARTS OLYMPIACOS AEK ATHENS PANATHINAIKOS PAOK CLUB BRUGGE ANDERLECHT ST MIRREN ASTON VILLA EVERTON INTER GENOA BURNLEY 023 024 007 025 INCLUDED 026 SOON... INCLUDED 043 007 102 SOON... 060 061 118 062 063 097 003 098 021 128 129 CURRENTLY AVAILABLE individually 5 5 2 3 9 10 5 7 10 10 4 7 5 10 9 3 8 in the counter attack store 7 4 LEICESTER LIVERPOOL MAN CITY MAN UTD NEWCASTLE NORWICH HELLAS JUVENTUS JUVENTUS LAZIO LECCE PARMA HIBS ICT KILMARNOCK LIVINGSTON MOTHERWELL SPORTING CP BENFICA FC PORTO / BRAGA BOAVISTA DUKLA PRAGUE 001 002 003 004 005 VERONA CLASSIC / MODERN NAPOLI IFK GOTHENBURG UDINESE 027 028 029 030 031 120 044 SOON... 045 046 059 091 064 SOON 001 INCLUDED 094 100 101 004 036 130 131 4 10 11 4 3 CHELSEA BARCELONA BENFICA WEST HAM RIVER PLATE 2 3 4 11 11 3 7 7 8 5 7 4 5 11 4 8 11 SCHALKE INVERNESS LIVERPOOL ASTON VILLA RANGERS C.PALACE ABERDEEN BURNLEY SHEFF UTD SOUTHAMPTON TOTTENHAM WATFORD WOLVES BRADFORD ROMA SPAL SAMPDORIA SASSUOLO TORINO PALERMO RANGERS ROSS CO. -

University of Peloponnese Faculty of Human Movement

UNIVERSITY OF PELOPONNESE FACULTY OF HUMAN MOVEMENT AND QUALITY OF LIFE DEPARTMENT OF SPORTS MANAGEMENT RESEARCH ON BASKETBALL TRENDS AND EVOLUTION METHODOLOGIES IN COUNTRIES WITH LOW POPULARITY OF THE SPORT: THE CASE OF PORTUGAL AND THE COMPAL AIR (3V3) SCHOOL TOURNAMENT by Panagiotis Chatziavgoustidis, BSc. A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Sports Organization and Management of University of Peloponnese in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Master of Sciences Degree Sparta, 2015 1 Copyright © Χατζηαυγουστίδης Παναγιώτης, 2015 Με επιφύλαξη κάθε δικαιώματος. All rights reserved. Απαγορεύεται η αντιγραφή, αποθήκευση και διανομή της παρούσας εργασίας, εξ ολοκλήρου ή τμήματος αυτής, για εμπορικό σκοπό. Επιτρέπεται η ανατύπωση, αποθήκευση και διανομή για σκοπό μη κερδοσκοπικό, εκπαιδευτικής ή ερευνητικής φύσης, υπό την προϋπόθεση να αναφέρεται η πηγή προέλευσης και να διατηρείται το παρόν μήνυμα. Ερωτήματα που αφορούν τη χρήση της εργασίας για κερδοσκοπικό σκοπό πρέπει να απευθύνονται προς τον συγγραφέα. Οι απόψεις και τα συμπεράσματα που περιέχονται σε αυτό το έγγραφο εκφράζουν τον συγγραφέα και δεν πρέπει να ερμηνευθεί ότι αντιπροσωπεύουν τις επίσημες θέσεις του Πανεπιστημίου Πελοποννήσου του Τμήματος Οργάνωσης και Διαχείρισης Αθλητισμού 2 ABSTRACT Panagiotis Chatziavgoustidis: Research on basketball trends and evolution methodologies in countries with low popularity of the sport: Τhe case of Portugal and the Compal Air (3v3) school tournament (With the supervision of Dr. Athanasios Kriemadis, Associate Professor) The scope of the current thesis is to analyze and understand the reason why basketball is a sport of low popularity in Portugal. Moreover, already applied strategies will be observed and ideas that could provide a greater level of help to the Portuguese Basketball Federation will be given. -

As Fontes De Informação No Porto Canal- O Caso Do Jornal Diário Ana Isabel Moreira Moura

MESTRADO EM CIÊNCIAS DA COMUNICAÇÃO VARIANTE DE ESTUDOS DE MEDIA E JORNALISMO As fontes de informação no Porto Canal- o caso do Jornal Diário Ana Isabel Moreira Moura M 2019 Ana Isabel Moreira Moura As fontes de informação do Porto Canal- o caso do Jornal Diário Relatório de estágio realizado no âmbito do Mestrado em Ciências da Comunicação, orientado pelo Professor Doutor Paulo Frias da Costa Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto setembro de 2019 As Fontes de Informação do Porto Canal- o caso do Jornal Diário Ana Isabel Moreira Moura Relatório de estágio realizado no âmbito do Mestrado em Ciências da Comunicação, orientado pelo professor Doutor Paulo Frias da Costa Membros do Júri Professor Doutor Paulo Frias da Costa Faculdade de Letras- Universidade do Porto Professor Doutor Pedro Costa Faculdade de Engenharia- Universidade do Porto Professor Doutor Hélder Bastos Faculdade de Letras- Universidade do Porto Classificação obtida: 16 valores Sumário Declaração de honra ....................................................................................................... 10 Agradecimento………………………………………………………………………..….9 Resumo…………………………………………………………………………………12 0 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………13 Índice de gráficos circulares ........................................................................................... 12 Introdução ....................................................................................................................... 15 Capítulo 1 – O estágio ................................................................................................... -

NBA MLB NFL NHL MLS WNBA American Athletic

Facilities That Have the AlterG® ® Anti-Gravity Treadmill Texas Rangers LA Galaxy NBA Toronto Blue Jays (2) Minnesota United Atlanta Hawks (2) Washington Nationals (2) New York City FC Brooklyn Nets New York Red Bulls Boston Celtics Orlando City SC Charlotte Hornets (2) NFL Real Salt Lake Chicago Bulls Atlanta Falcons San Jose Earthquakes Cleveland Cavaliers Sporting KC Denver Nuggets Arizona Cardinals (2) Detroit Pistons Baltimore Ravens Golden State Warriors Buffalo Bills WNBA Houston Rockets Carolina Panthers Indiana Pacers Chicago Bears New York Liberty Los Angeles Lakers Cincinnati Bengals Los Angeles Clippers Cleveland Browns COLLEGE/UNIVERSITY Memphis Grizzlies Dallas Cowboys PHYSICAL THERAPY (3) PROGRAMS Miami Heat Denver Broncos Milwaukee Bucks (2) Detroit Lions Florida Gulf Coast University Minnesota Timberwolves Green Bay Packers Chapman University (2) New York Knicks Houston Texans Northern Arizona University New Orleans Pelicans Indianapolis Colts Marquette University Oklahoma City Thunder Jacksonville Jaguars University of Southern California Orlando Magic Kansas City Chiefs (2) University of Delaware Philadelphia 76ers Los Angeles Rams Samuel Merritt University Phoenix Suns (2) Miami Dolphins Georgia Regents University Hardin- Portland Trailblazers Sacramento Minnesota Vikings Simmons University Kings New England Patriots High Point University San Antonio Spurs New Orleans Saints Long Beach State University Utah Jazz New York Giants Chapman University (2) Washington Wizards New York Jets University of Texas at Arlington- -

Oxidative Stress in Asthmatic and Non‐

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositório Aberto da Universidade do Porto Accepted: 23 April 2017 DOI: 10.1111/pai.12729 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Upper Airways Oxidative stress in asthmatic and non- asthmatic adolescent swimmers—A breathomics approach Mariana Couto1,2,3 | Corália Barbosa4 | Diana Silva1,5 | Alisa Rudnitskaya6 | Luís Delgado1,3,5 | André Moreira1,5,7 | Sílvia M. Rocha4 1Basic and Clinical Immunology Unit, Department of Pathology, Faculty of Abstract Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal We hypothesize that oxidative stress induced by trichloramine exposure during swim- 2 Immunoallergology, Hospital & Instituto CUF ming could be related to etiopathogenesis of asthma among elite swimmers. Porto, Porto, Portugal Aim: To investigate the effect of a swimming training session on oxidative stress mark- 3CINTESIS, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal ers of asthmatic compared to non- asthmatic elite swimmers using exhaled breath (EB) 4Department of Chemistry & metabolomics. QOPNA, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal Methods: Elite swimmers annually screened in our department (n=27) were invited and 5Imunoalergologia, Centro Hospitalar São ® João, EPE, Porto, Portugal those who agreed to participate (n=20, of which 9 with asthma) had EB collected (Tedlar 6Department of Chemistry & bags) before and after a swimming training session. SPME fiber (DVB/CAR/PDMS) was CESAM, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal used to extract EB metabolites followed by a multidimensional gas chromatography anal- 7EPIUnit Institute of Public Health, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal ysis (GC×GC- ToFMS). Dataset comprises eight metabolites end products of lipid peroxi- dation: five aliphatic alkanes (nonane, 2,2,4,6,6- pentamethylheptane, decane, dodecane, Correspondence Mariana Couto, Serviço e Laboratório and tetradecane) and three aldehydes (nonanal, decanal, and dodecanal). -

The-KA-Club-Rating-2Q-2021 / June 30, 2021 the KA the Kick Algorithms ™

the-KA-Club-Rating-2Q-2021 / June 30, 2021 www.kickalgor.com the KA the Kick Algorithms ™ Club Country Country League Conf/Fed Class Coef +/- Place up/down Class Zone/Region Country Cluster Continent ⦿ 1 Manchester City FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,928 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 2 FC Bayern München GER GER � GER UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,907 -1 UEFA Central DACH Countries Western Europe ≡ ⦿ 3 FC Barcelona ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,854 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 4 Liverpool FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,845 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 5 Real Madrid CF ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,786 -1 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 6 Chelsea FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,752 +4 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ≡ ⦿ 7 Paris Saint-Germain FRA FRA � FRA UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,750 UEFA Western France / overseas territories Continental Europe ⦿ 8 Juventus ITA ITA � ITA UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,749 -2 UEFA Central / East Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) Mediterranean Zone ⦿ 9 Club Atlético de Madrid ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,676 -1 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 10 Manchester United FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,643 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 11 Tottenham Hotspur FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,628 -2 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ≡ ⬇ 12 Borussia Dortmund GER GER � GER UEFA 2 Primary High ★★★★★ 1,541 UEFA Central DACH Countries Western Europe ≡ ⦿ 13 Sevilla FC ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 2 Primary High ★★★★★ 1,531 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. -

Claremont Mckenna College an Exploration Into the Influence Of

Claremont McKenna College An Exploration into the Influence of Transfers on Share Prices for Publicly Traded Football Clubs SUBMITTED TO Professor Richard Burdekin AND DEAN NICHOLAS WARNER BY ANTHONY CONTRERAS For SENIOR THESIS Spring 2015 April 27, 2015 1 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................4 Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction .....................................................................................................................6 II. Literature Review ...........................................................................................................8 III. The Present Paper .......................................................................................................13 IV. Background to International Football .........................................................................15 IV.1 The Transfer Window .......................................................................................15 IV.2 The Transfer Process ....................................................................................... 16 IV.3 Ownership of Football Clubs ...........................................................................16 V. Preliminary Analysis ....................................................................................................17 V.1 Data Sources ......................................................................................................17 -

Uefa Champions League

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - 2017/18 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS (First leg: 0-0) Arena Națională - Bucharest Wednesday 23 August 2017 FCSB 20.45CET (21.45 local time) Sporting Clube de Play-off, Second leg Portugal Last updated 21/08/2017 12:58CET UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE OFFICIAL SPONSORS Match officials 2 Legend 3 1 FCSB - Sporting Clube de Portugal Wednesday 23 August 2017 - 20.45CET (21.45 local time) Match press kit Arena Națională, Bucharest Match officials Referee Cüneyt Çakır (TUR) Assistant referees Bahattin Duran (TUR) , Tarik Ongun (TUR) Additional assistant referees Hüseyin Göçek (TUR) , Barış Şimşek (TUR) Fourth official Esat Sancaktar (TUR) UEFA Delegate Peter Lundström (FIN) UEFA Referee observer Uno Tutk (EST) Referee UEFA Champions Name Date of birth UEFA matches League matches Cüneyt Çakır 23/11/1976 36 93 UEFA Champions League matches involving teams from the two countries involved in this match Stage Date Competition Home Away Result Venue reached 22/11/2011 UCL GS Manchester United FC SL Benfica 2-2 Manchester 02/10/2012 UCL GS SL Benfica FC Barcelona 0-2 Lisbon 18/09/2013 UCL GS FC Schalke 04 FCSB 3-0 Gelsenkirchen 30/09/2014 UCL GS FC Shakhtar Donetsk FC Porto 2-2 Lviv 18/08/2015 UCL PO Sporting Clube de Portugal PFC CSKA Moskva 2-1 Lisbon 09/12/2015 UCL GS Chelsea FC FC Porto 2-0 London 27/09/2016 UCL GS Leicester City FC FC Porto 1-0 Leicester Other matches involving teams from either of the two countries involved in this match Stage Date Competition Home Away Result Venue reached 18/07/2007 U19 GS-FT Spain Portugal 1-1 -

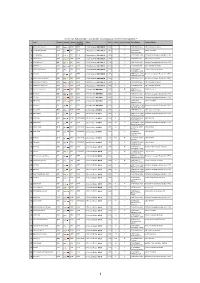

VIII Campeonato Da LPB • LPB Sénior • Masculino 1ª FASE

Calendário Provisório VIII Campeonato da LPB • LPB Sénior • Masculino 1ª FASE Equipas Participantes Basquete Clube Amigos do Eléctrico Futebol Clube Galitos Futebol Clube de Basq.da Futebol Clube do Porto Clube Barcelos Madeira,Basq.SAD Eléctrico F.C. FC Porto Galitos FC Basquete de CAB Madeira SAD Barcelos Sport Clube Maia Basket Clube A.D.O. • Sport Lisboa e União Lusitânia Maia Basket Basquetebol Benfica Desportiva Lusitânia da Ass. Desp. Sport Lisboa Oliveirense Ovarense, SAD Benfica UD Oliveirense Ovarense Dolce Vita Vitória Sport Clube Vitória SC• Guimarães 1ª VOLTA 1º jogo (10/10/2015 00.00) Jogo nº Visitado Visitante Data Hora Recinto Jogo Resultado 258 Basquete de Barcelos Lusitânia 10/10/2015 00.00 Esc Sec Barcelos / 259 UD Oliveirense CAB Madeira SAD 10/10/2015 00.00 Dr Salvador Machado / 260 Sport Lisboa Benfica Vitória SC•Guimarães 10/10/2015 00.00 Pav. Fidelidade / 261 Ovarense Dolce Vita Maia Basket 10/10/2015 00.00 Arena Dolce Vita / 262 Eléctrico F.C. FC Porto 10/10/2015 00.00 Mun. Ponte de Sor / 1/6 2º jogo (17/10/2015 00.00) Jogo nº Visitado Visitante Data Hora Recinto Jogo Resultado 263 Basquete de Barcelos Eléctrico F.C. 11/10/2015 00.00 Esc Sec Barcelos / 264 Galitos FC CAB Madeira SAD 11/10/2015 00.00 P Mun Luís Carvalho / 265 FC Porto Ovarense Dolce Vita 11/10/2015 00.00 Dragão Caixa / 266 UD Oliveirense Lusitânia 11/10/2015 00.00 Dr Salvador Machado / 267 Maia Basket Sport Lisboa Benfica 11/10/2015 00.00 Mun. -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

LES CHAÎNES TV by Dans Votre Offre Box Très Haut Débit Ou Box 4K De SFR

LES CHAÎNES TV BY Dans votre offre box Très Haut Débit ou box 4K de SFR TNT NATIONALE INFORMATION MUSIQUE EN LANGUE FRANÇAISE NOTRE SÉLÉCTION POUR VOUS TÉLÉ-ACHAT SPORT INFORMATION INTERNATIONALE MULTIPLEX SPORT & ÉCONOMIQUE EN VF CINÉMA ADULTE SÉRIES ET DIVERTISSEMENT DÉCOUVERTE & STYLE DE VIE RÉGIONALES ET LOCALES SERVICE JEUNESSE INFORMATION INTERNATIONALE CHAÎNES GÉNÉRALISTES NOUVELLE GÉNÉRATION MONDE 0 Mosaïque 34 SFR Sport 3 73 TV Breizh 1 TF1 35 SFR Sport 4K 74 TV5 Monde 2 France 2 36 SFR Sport 5 89 Canal info 3 France 3 37 BFM Sport 95 BFM TV 4 Canal+ en clair 38 BFM Paris 96 BFM Sport 5 France 5 39 Discovery Channel 97 BFM Business 6 M6 40 Discovery Science 98 BFM Paris 7 Arte 42 Discovery ID 99 CNews 8 C8 43 My Cuisine 100 LCI 9 W9 46 BFM Business 101 Franceinfo: 10 TMC 47 Euronews 102 LCP-AN 11 NT1 48 France 24 103 LCP- AN 24/24 12 NRJ12 49 i24 News 104 Public Senat 24/24 13 LCP-AN 50 13ème RUE 105 La chaîne météo 14 France 4 51 Syfy 110 SFR Sport 1 15 BFM TV 52 E! Entertainment 111 SFR Sport 2 16 CNews 53 Discovery ID 112 SFR Sport 3 17 CStar 55 My Cuisine 113 SFR Sport 4K 18 Gulli 56 MTV 114 SFR Sport 5 19 France Ô 57 MCM 115 beIN SPORTS 1 20 HD1 58 AB 1 116 beIN SPORTS 2 21 La chaîne L’Équipe 59 Série Club 117 beIN SPORTS 3 22 6ter 60 Game One 118 Canal+ Sport 23 Numéro 23 61 Game One +1 119 Equidia Live 24 RMC Découverte 62 Vivolta 120 Equidia Life 25 Chérie 25 63 J-One 121 OM TV 26 LCI 64 BET 122 OL TV 27 Franceinfo: 66 Netflix 123 Girondins TV 31 Altice Studio 70 Paris Première 124 Motorsport TV 32 SFR Sport 1 71 Téva 125 AB Moteurs 33 SFR Sport 2 72 RTL 9 126 Golf Channel 127 La chaîne L’Équipe 190 Luxe TV 264 TRACE TOCA 129 BFM Sport 191 Fashion TV 265 TRACE TROPICAL 130 Trace Sport Stars 192 Men’s Up 266 TRACE GOSPEL 139 Barker SFR Play VOD illim. -

Rivalry in the Football Industry and Its Impact on the Stock Prices of Listed Football Clubs Master Thesis Finance

Rivalry in the football industry and its impact on the stock prices of listed football clubs Master Thesis Finance BY W.J.Tankink Supervisor: J.H. von Eije Groningen, January 11, 2018 University of Groningen Faculty of Economics and Business MSc Finance Words: 9381 Abstract Rivalry in the football industry is examined in this paper as it analyses rivalry effects on stock price performance of football clubs. It does not matter which sport is exercised and at what level, rivalry among clubs is one of the main sources of attractiveness of a league. The rivalry among football clubs leads to a positive “mood” in case the rival loses and leads to a negative “mood” in case the rival has a for them positive match result. It is hypothesised that these emotions due to the performance of the period rival affect the stock price performance of the focal football club. This study shows that there is evidence that the results of the period rival can have an impact on the investment decisions of club supporters. Keywords: Rivalry, Period Rivalry, Football clubs, European Football, Stock performance 2 1. Introduction Football, or what they call it in the United States soccer, is a well-known sport exercised all around the world. It all started in 1887. From then on it was allowed by the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) to recruit football players as an individual football club. This was the start of, what is familiar to us now as, professional football. In other words, money made its entrance here and the role of money has increased a lot since then (Dobson and Goddard, 1998).