Blueprint 3: Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definition and Methods for the Carbon Handprint of Buildings

Definition and methods for the carbon handprint of buildings 8.2.2021 Authors: Tarja Häkkinen [email protected] Sylviane Nibel [email protected] Harpa Birgisdottir [email protected] 2 Table of contents 1 Background ..................................................................................................................... 4 2 Objectives........................................................................................................................ 7 3 Methods and execution of work ...................................................................................... 8 Study of literature ................................................................................................................... 8 Study of possible handprint cases for buildings ..................................................................... 9 Study of relevant standards .................................................................................................. 10 4 Study of literature.......................................................................................................... 11 Definitions and approaches .................................................................................................. 11 Handprint thinking................................................................................................................ 13 Needs and barriers for the handprint concept ..................................................................... 14 Measures that improve carbon handprint .......................................................................... -

HTTP Cookie - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 14/05/2014

HTTP cookie - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 14/05/2014 Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search HTTP cookie From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Navigation A cookie, also known as an HTTP cookie, web cookie, or browser HTTP Main page cookie, is a small piece of data sent from a website and stored in a Persistence · Compression · HTTPS · Contents user's web browser while the user is browsing that website. Every time Request methods Featured content the user loads the website, the browser sends the cookie back to the OPTIONS · GET · HEAD · POST · PUT · Current events server to notify the website of the user's previous activity.[1] Cookies DELETE · TRACE · CONNECT · PATCH · Random article Donate to Wikipedia were designed to be a reliable mechanism for websites to remember Header fields Wikimedia Shop stateful information (such as items in a shopping cart) or to record the Cookie · ETag · Location · HTTP referer · DNT user's browsing activity (including clicking particular buttons, logging in, · X-Forwarded-For · Interaction or recording which pages were visited by the user as far back as months Status codes or years ago). 301 Moved Permanently · 302 Found · Help 303 See Other · 403 Forbidden · About Wikipedia Although cookies cannot carry viruses, and cannot install malware on 404 Not Found · [2] Community portal the host computer, tracking cookies and especially third-party v · t · e · Recent changes tracking cookies are commonly used as ways to compile long-term Contact page records of individuals' browsing histories—a potential privacy concern that prompted European[3] and U.S. -

Discontinued Browsers List

Discontinued Browsers List Look back into history at the fallen windows of yesteryear. Welcome to the dead pool. We include both officially discontinued, as well as those that have not updated. If you are interested in browsers that still work, try our big browser list. All links open in new windows. 1. Abaco (discontinued) http://lab-fgb.com/abaco 2. Acoo (last updated 2009) http://www.acoobrowser.com 3. Amaya (discontinued 2013) https://www.w3.org/Amaya 4. AOL Explorer (discontinued 2006) https://www.aol.com 5. AMosaic (discontinued in 2006) No website 6. Arachne (last updated 2013) http://www.glennmcc.org 7. Arena (discontinued in 1998) https://www.w3.org/Arena 8. Ariadna (discontinued in 1998) http://www.ariadna.ru 9. Arora (discontinued in 2011) https://github.com/Arora/arora 10. AWeb (last updated 2001) http://www.amitrix.com/aweb.html 11. Baidu (discontinued 2019) https://liulanqi.baidu.com 12. Beamrise (last updated 2014) http://www.sien.com 13. Beonex Communicator (discontinued in 2004) https://www.beonex.com 14. BlackHawk (last updated 2015) http://www.netgate.sk/blackhawk 15. Bolt (discontinued 2011) No website 16. Browse3d (last updated 2005) http://www.browse3d.com 17. Browzar (last updated 2013) http://www.browzar.com 18. Camino (discontinued in 2013) http://caminobrowser.org 19. Classilla (last updated 2014) https://www.floodgap.com/software/classilla 20. CometBird (discontinued 2015) http://www.cometbird.com 21. Conkeror (last updated 2016) http://conkeror.org 22. Crazy Browser (last updated 2013) No website 23. Deepnet Explorer (discontinued in 2006) http://www.deepnetexplorer.com 24. Enigma (last updated 2012) No website 25. -

Stefan N. Grösser Arcadio Reyes-Lecuona Göran Granholm

Stefan N. Grösser Arcadio Reyes-Lecuona Göran Granholm Editors Dynamics of Long-Life Assets From Technology Adaptation to Upgrading the Business Model Dynamics of Long-Life Assets Stefan N. Grösser • Arcadio Reyes-Lecuona Göran Granholm Editors Dynamics of Long-Life Assets From Technology Adaptation to Upgrading the Business Model Editors Stefan N. Grösser Göran Granholm School of Management VTT Technical Research Centre Bern University of Applied Sciences of Finland Ltd. Bern Espoo Switzerland Finland Arcadio Reyes-Lecuona E.T.S.I. de Telecomunicación Universidad de Málaga Málaga Spain ISBN 978-3-319-45437-5 ISBN 978-3-319-45438-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-45438-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017932015 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and the Author(s) 2017. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. -

Automatic Monitoring for Interactive Performance and Power Reduction

Automatic Monitoring for Interactive Performance and Power Reduction by Krisztián Flautner A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Computer Science and Engineering) in The University of Michigan 2001 Doctoral Committee: Professor Trevor Mudge, Chair Assistant Professor Todd M. Austin Professor Kenneth G. Powell Assistant Professor Steven K. Reinhardt Assistant Professor Gary Tyson Krisztián Flautner © 2001 All Rights Reserved To my grandmother, Eleonóra Majorosy. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my mother, Eleonóra Arató who, at first sceptical of me spending too much time with a brand new Commodore 64, eventually gave up trying to push me towards medical school and has been a steadfast supporter of my studies ever since. My wife, Krisztina Gerhardt helped me gather the focus to finish this dissertation. I thank my stepfather, Cecil Eby, whose adventures with computers have shown me time again that even simple triumphs over the machine can bring great satisfaction. The research that eventually led to this dissertation began under Rich Uhlig’s watch while I was at the Intel Microprocessor Research Lab in Portland, Oregon. His comments and ideas greatly influenced the initial direction. Steve Reinhardt has been very helpful at getting to the bottom of the issues and forcing me to elaborate on the details. Conversations with and the compiler course taught by Peter Bird had a great impact on my view of computers. I would like to thank him for many afternoons’ worth of interesting discussions. I would also like to thank my fellow graduate students, Matt Pos- tiff and David Greene, who have been willing and helpful test subjects for many of the ideas in this dissertation. -

United States V.Microsoft

United States v. Microsoft 1 United States v. Microsoft United States vs. Microsoft was a set of consolidated civil actions filed against Microsoft Corporation pursuant to the Sherman Antitrust Act on May 18, 1998 by the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) and 20 U.S. states. Joel I. Klein was the lead prosecutor. The plaintiffs alleged that Microsoft abused monopoly power on Intel-based personal computers in its handling of operating system sales and web browser sales. The issue central to the case was whether Microsoft was allowed to bundle its flagship Internet Explorer (IE) web browser software with its Microsoft Windows operating system. Bundling them together is alleged to have been responsible for Microsoft's victory in the browser wars as every Windows user had a copy of Internet Explorer. It was further alleged that this restricted the market for competing web browsers (such as Netscape Navigator or Opera) that were slow to download over a modem or had to be purchased at a store. Underlying these disputes were questions over whether Microsoft altered or manipulated its application programming interfaces (APIs) to favor Internet Explorer over third party web browsers, Microsoft's conduct in forming restrictive licensing agreements with original equipment manufacturer (OEMs), and Microsoft's intent in its course of conduct. Microsoft stated that the merging of Microsoft Windows and Internet Explorer was the result of innovation and competition, that the two were now the same product and were inextricably linked together and that consumers were now getting all the benefits of IE for free. Those who opposed Microsoft's position countered that the browser was still a distinct and separate product which did not need to be tied to the operating system, since a separate version of Internet Explorer was available for Mac OS. -

Programación En Internet Programación En Internet

Programación en Internet Tema 1. Programación basada en la Web Contenido 1. Introducción 2. Notas históricas 3. Arquitectura Cliente/Servidor 4. Protocolo HTTP 5. Tecnologías del lado del cliente 6. Tecnologías del lado del servidor Programación en Internet Tema 1. Programación basada en la Web Contenido 1. Introducción 2. Notas históricas 3. Arquitectura Cliente/Servidor 4. Protocolo HTTP 5. Tecnologías del lado del cliente 6. Tecnologías del lado del servidor 1 Introducción ¿ Qué consideramos por “Programación en Internet” ? Programación basada en el World Wide Web Características Modelo Cliente/Servidor Cliente : Navegador o Browser (Internet Explorer, Netscape, etc…) Servidor: servidor web o web server (Apache, IIS, etc…) Protocolo: HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) Aplicación web = Página Web + dinámica HTML (o XHTML) Imágenes, sonidos, etc Programación para ejecución en el cliente (Javascript, VBScript, Applets) Programación para ejecución en el servidor (CGI, Servlets, JSP, ASP, PHP) I. T. Informática de Gestión Universidad de Huelva Programación en Internet Programación en Internet Tema 1. Programación basada en la Web Contenido 1. Introducción 2. Notas históricas 3. Arquitectura Cliente/Servidor 4. Protocolo HTTP 5. Tecnologías del lado del cliente 6. Tecnologías del lado del servidor 2 Notas históricas 1969 ARPANET - Network Control Protocol or NCP 1973-1983 ARPANET – Familia de protocolo TCP/IP 1983 ARPANET se divide en MILNET (militar) y ARPANET (investigación) 1984 NSFNET es creada por Fundación Nacional para la Ciencia (NSF - National Science Fundation) 1989 Tim Berners-Lee (CERN) propone un sistema de hipertexto para comunicación 1990 Tim Berners-Lee utiliza HTML, HTTP y un cliente (browser) 1993 Marc Andreesen (NCSA) desarrolla MOSAIC 1994 Netscape 1 1995 Internet Explorer 1 I. -

CA Risk Analytics® - 5.2 Administrating

CA Risk Analytics® - 5.2 Administrating Date: 31-Dec-2014 This Documentation, which includes embedded help systems and electronically distributed materials, (hereinafter referred to as the “Documentation”) is for your informational purposes only and is subject to change or withdrawal by CA at any time. This Documentation may not be copied, transferred, reproduced, disclosed, modified or duplicated, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of CA. This Documentation is confidential and proprietary information of CA and may not be disclosed by you or used for any purpose other than as may be permitted in (i) a separate agreement between you and CA governing your use of the CA software to which the Documentation relates; or (ii) a separate confidentiality agreement between you and CA. Notwithstanding the foregoing, if you are a licensed user of the software product(s) addressed in the Documentation, you may print or otherwise make available a reasonable number of copies of the Documentation for internal use by you and your employees in connection with that software, provided that all CA copyright notices and legends are affixed to each reproduced copy. The right to print or otherwise make available copies of the Documentation is limited to the period during which the applicable license for such software remains in full force and effect. Should the license terminate for any reason, it is your responsibility to certify in writing to CA that all copies and partial copies of the Documentation have been returned to CA or destroyed. TO THE EXTENT PERMITTED BY APPLICABLE LAW, CA PROVIDES THIS DOCUMENTATION “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, OR NONINFRINGEMENT. -

Szakdolgozat

Szakdolgozat Miskolci Egyetem Multidimenzionális tanszéki oktatási tabló Készítette: Tóth Béla Programtervező informatikus Korszerű web-technológiák Témavezető: Dr. Dudás László egyetemi docens Miskolc, 2016 Miskolci Egyetem Gépészmérnöki és Informatikai Kar Alkalmazott Matematikai Tanszék Szám: Szakdolgozat Feladat Tóth Béla Hallgató (HVQ0DL) programtervező informatikus jelölt részére. A szakdolgozat tárgyköre: Webfejlesztés A szakdolgozat címe: Multidimenzionális tanszéki oktatási tabló A feladat részletezése: WAMP kiszolgáló programcsomag bemutatása. Felhasznált technológiák (AJAX, Microsoft Office Excel makrók), keretrendszer (Boot- strap), komponens (Select2), programkönyvtár (jQuery) áttekintő jellegű ismertetése. A fenti technológiák felhasználásával webalkalmazás létrehozása, melynek célja: Kényelmes áttekinthetőséget nyújtani egy tanszék oktatott tárgyairól, azok tematika- nézetén, oktatói kötődések nézetén és szak, szakirány kötődések nézetén keresztül. Funkciói, szolgáltatásai: • A tanszék oktatott tárgyainak listája. • Egy kiválasztott tárgy tantárgyi lapja. • Egy kiválasztott tárgy megjelenése az elmúlt 3 félév órarendjében. • Egy kiválasztott tárgy oktatójához tartozó további tárgyak megjelenítése. • Egy kiválasztott tárgy kapcsán azon szakok, szakirányok, sávok megjelenítése, amelyeken a tárgyat oktatja a tanszék. Ezen nézetek között kényelmes, egy-két kattintásos átmenetek biztosítása az áttekin- tések könnyű realizálása érdekében. Témavezető: Dr. Dudás László, egyetemi docens A feladat kiadásának ideje: 2016.01.18. A feladat -

Haiku (Operating System) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Haiku (operating system) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Haiku is a free and open-source operating system compatible with the now discontinued BeOS. Its development began in Haiku 2001, and the operating system became self-hosting in 2008.[4] The first alpha release was made in September 2009, and the most recent was November 2012; development is ongoing as of 2017 with nightly releases. Haiku is supported by Haiku, Inc., a non-profit organization based in Rochester, New York, United States, founded in 2003 by former project leader Michael Phipps.[5] Contents 1 History 2 Technology 3 Package management Developer Haiku, Inc. OS family BeOS 4 Compatibility with BeOS Working state Alpha 5 Beyond R1 Source model Open source Initial release 2002 6 System requirements Latest preview R1 Alpha 4.1 / 7 See also November 14, 2012 8 References Marketing target Personal computer 9 External links Available in Multilingual Platforms IA-32, ARM,[1] History and x86-64[2][3] Kernel type Hybrid Haiku began as the OpenBeOS project in 2001, the year that Be, Inc. was bought by Palm, Inc. and BeOS development was Default user interface OpenTracker discontinued; the focus of the project was to support the BeOS user community by creating an open-source, backward- compatible replacement for BeOS. The first project by OpenBeOS was a community-created "stop-gap" update for BeOS 5.0.3 License MIT License in 2002. In 2003, the non-profit organization Haiku, Inc. was registered in Rochester, New York, to financially support and Be Sample development, and in 2004, after a notification of infringement of Palm's trademark of the BeOS name was sent to OpenBeOS, Code License the project was renamed Haiku. -

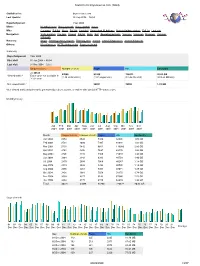

Statistics for Brynosaurus.Com (2004)

Statistics for brynosaurus.com (2004) Statistics for: brynosaurus.com Last Update: 26 Sep 2006 − 03:56 Reported period: Year 2004 When: Monthly history Days of month Days of week Hours Who: Countries Full list Hosts Full list Last visit Unresolved IP Address Robots/Spiders visitors Full list Last visit Navigation: Visits duration File type Viewed Full list Entry Exit Operating Systems Versions Unknown Browsers Versions Unknown Referers: Origin Refering search engines Refering sites Search Search Keyphrases Search Keywords Others: Miscellaneous HTTP Status codes Pages not found Summary Reported period Year 2004 First visit 01 Jan 2004 − 00:04 Last visit 31 Dec 2004 − 23:57 Unique visitors Number of visits Pages Hits Bandwidth <= 40525 47088 85260 726872 20.63 GB Viewed traffic * Exact value not available in (1.16 visits/visitor) (1.81 pages/visit) (15.43 hits/visit) (459.33 KB/visit) 'Year' view Not viewed traffic * 56661 78092 1.91 GB * Not viewed traffic includes traffic generated by robots, worms, or replies with special HTTP status codes. Monthly history Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 2004 Month Unique visitors Number of visits Pages Hits Bandwidth Jan 2004 3254 3542 5336 34926 1.06 GB Feb 2004 3721 4080 7997 68946 1.83 GB Mar 2004 5103 5842 9661 116080 2.89 GB Apr 2004 3761 4306 7697 69176 1.86 GB May 2004 3796 4415 7466 71072 1.96 GB Jun 2004 2664 3143 6283 49758 1.40 GB Jul 2004 2470 2908 5066 40287 1.18 GB Aug 2004 2279 2836 5394 40026 1.14 GB Sep 2004 2955 -

AR Layout Introduction 004.Indd

Annual Review 2017 A Distinctive Learning Experience Contents Achievements . 3 A stimulating learning culture Forewords . 6 Inspiring staff . 54 Mission, Vision and Foundational Values . 10 Excellence in research and innovation . 59 #MyChesterStory . 11 Publications . .. 66 Our campuses and sites . 12 Staff engagement . .. 68 Conferences. 72 Factfile A holistic student experience Eminent guests . 75 Established: 1839 . The University is one of the Honorary graduates include: Joining the University community . 16 Investment in facilities. 78 longest established English higher education HRH The Prince of Wales KG, KT, GCB, OM, AK, CD, The student journey . 17 Commitment to sustainability . .. 80 establishments still in its original form, predating all QSO, PC, ADC; Joan Bakewell, The Rt Hon Baroness but Oxford, Cambridge, London and Durham . Bakewell of Stockport, DBE; The Most Rev and Rt Hon Outstanding student support . 23 Dr John Sentamu, Archbishop of York; Terry Waite Students: 20,700 (69% undergraduates, 31% Chaplaincy . 28 A community focus CBE; Sir Ian Botham OBE; Loyd Grossman CBE, FSA; Sir postgraduates) . Andrew Motion FRSL; Sir Ken Dodd OBE; Tim Firth; Sue Enriching educational opportunities . 29 Outreach activities . 86 Staff: 1,660 . Johnston OBE; Phil Redmond CBE; Gyles Brandreth; Volunteering and mentoring . 36 Educational partnerships . 88 Matthew Kelly OBE; Estelle Morris, The Rt Hon Chancellor: Dr Gyles Brandreth . Baroness Morris of Yardley; Ronald Pickup; The Earl of Innovative student research and Engaging with business . 92 Vice-Chancellor: Canon Professor Tim Wheeler DL . Derby; Sir Tony Robinson OBE; Neville Chamberlain creative projects . 41 Beyond our boundaries . 95 CBE; Viscount Michael Ashbrook JP, DL; Professor Sir Campuses: Four in Chester, one in Warrington, one Enhancing employability .