Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

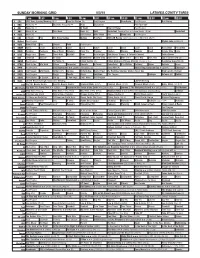

Sunday Morning Grid 5/3/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/3/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program NewsRadio Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Equestrian PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Brooklyn Nets at Atlanta Hawks. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Pre-Race NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Afghan Luke (2011) (R) 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Fast. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Father Brown 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

FRANCIS MARION UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTION of PROPOSED NEW COURSE Department/School H

FRANCIS MARION UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED NEW COURSE Department/School HONORS Date September 16, 2013 Course No. or level HNRS 270-279 Title HONORS SPECIAL TOPICS IN THE BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES Semester hours 3 Clock hours: Lecture 3 Laboratory 0 Prerequisites Membership in FMU Honors, or permission of Honors Director Enrollment expectation 15 Indicate any course for which this course is a (an) Modification N/A Substitute N/A Alternate N/A Name of person preparing course description: Jon Tuttle Department Chairperson’s /Dean’s Signature _______________________________________ Date of Implementation Fall 2014 Date of School/Department approval: September 13, 2013 Catalog description: 270-279 SPECIAL TOPICS IN THE BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES (3) (Prerequisite: membership in FMU Honors or permission of Honors Director.) Course topics may be interdisciplinary and cover innovative, non-traditional topics within the Behavioral Sciences. May be taken for General Education credit as an Area 4: Humanities/Social Sciences elective. May be applied as elective credit in applicable major with permission of chair or dean. Purpose: 1. For Whom (generally?): FMU Honors students, also others students with permission of instructor and Honors Director 2. What should the course do for the student? HNRS 270-279 will offer FMU Honors members enhanced learning options within the Behavioral Sciences beyond the common undergraduate curriculum and engage potential majors with unique, non-traditional topics. Teaching method/textbook and materials planned: Lecture, -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Trevino Uchicago 0330D 14659.Pdf

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO INSPIRATION AND NARRATIVE IN THE HOMERIC ODYSSEY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS BY NATALIE TREVINO CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2019 Contents LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................ v ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................. vii INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 I.1 Innovation, Aberration, and Metanarrative ............................................................................ 1 I.2 Scholarly Opinions, A History of Devaluation ...................................................................... 2 I.3 Decoding the Inscrutable: Genre, Inspiration, and The Poet ................................................. 6 I.4 Methodology: Studies in the Inspiration of Poets and Prophets, and Narratology .............. 14 I.5 Chapter Summaries .............................................................................................................. 18 I.6 Glossary .............................................................................................................................. -

2021 SPRING Pan Macmillan Spring Catalogue 2021.Pdf

PUBLICITY CONTACTS General enquiries [email protected] * * * * * * * Alice Dewing Rosie Wilson [email protected] [email protected] Amy Canavan Siobhan Slattery [email protected] [email protected] Camilla Elworthy [email protected] * * * * * * * Elinor Fewster [email protected] FREELANCE Emma Bravo Anna Pallai [email protected] [email protected] Gabriela Quattromini Caitlin Allen [email protected] [email protected] Grace Harrison Emma Draude [email protected] [email protected] Hannah Corbett Emma Harrow [email protected] [email protected] Jess Duffy Jamie-Lee Nardone [email protected] [email protected] Kate Green Laura Sherlock [email protected] [email protected] Philippa McEwan Ruth Cairns [email protected] [email protected] CONTENTs PICADOR MACMILLAN COLLECTOR’S LIBRARY MANTLE MACMILLAN PAN TOR BLUEBIRD ONE BOAT PICADOR The War of the Poor Eric Vuillard A short, brutal tale by the author of The Order of The Day: the story of a moment in Europe’s history when the poor rose up and banded together behind a fiery preacher, to challenge the entrenched powers of the ruling elite. The fight for equality begins in the streets. The history of inequality is a long and terrible one. And it’s not over yet. Short, sharp and devastating, The War of the Poor tells the story of a brutal episode from history, not as well known as tales of other popular uprisings, but one that deserves to be told. Sixteenth-century Europe: the Protestant Reformation takes on the powerful and the privileged. -

World Watch One in This Issue

WORLD WATCH ONE _ IN THIS ISSUE Introduction from the Editor Dianne “Hollywood” Wickes, Pine Island, FL Page 1 In Memoriam Scott “Camelot” Tate, Alamosa, CO Page 2 Buckaroo Crushes Cult Competition Tim “Tim Boo Ba” Monro, Renton, WA Page 3 Representing Team Banzai Charley “Mrs. Trooper” Todd, Evansville, IN Pages 4-5 Pimping Your Ride, Jet Car Style Chris “Cobalt” Dunham, Monrovia, IN Page 6 From Worf to Whorfin Scott Tate Pages 7-9 Buckaroo Banzai Fandom on the Internet: Dan “Big Shoulders” Berger, Libertyville, IL and Unseen Interviews from the Archives Sean “Figment” Murphy, Burke, VA Pages 10-15 Buckaroo Banzai Art from the Internet World Watch One Staff Pages 16-18 Hanoi Xan’s Rock ’N’ Roll Stranglehold! Jeffrey “Machine Rock” Morgan Page 19 INTERVIEW: Radford Polinsky Steve “Rainbow Kitty” Mattsson, Portland, OR Pages 20-24 Celebrating 35 Years Charley Todd Pages 25-26 Blue Blaze Irregulars Remember Edited by Dan Berger Pages 27-42 Remembering the Promotional Material Charley Todd Page 43 Banzai Trivia Scott Tate Page 44 INTERVIEW: Earl Mac Rauch Steve Mattsson Page 45 From the Files of Earl Mac Rauch Earl Mac Rauch Page 46 Sekrit Origins Tim Monro Page 47 The Buckaroo Banzai Production Binders Introduction and Overview Sean Murphy Page 48 Production Illustrations Dan Berger Pages 49-55 Storyboards Sean Murphy Pages 56-59 Script Comparison Steve Mattson Pages 60-61 The Essential Buckaroo Dewayne “Buckaroo Trooper” Todd, Evansville, IN Pages 62-66 Mystery Solved! World Watch One Staff Page 66 Team Banzai Events Calendar Scott Tate Page 67 15 Years of World Watch One Dan Berger Pages 68-70 Acknowledgements This installment of World Watch One clocked in at seventy pages, just a little over twice our usual page length. -

Winter 2012-2013

GRACE COMMUNION INTERNATIONAL Winter 2012/2013 Growing Together in Life & Faith Scripture: God’s Gift Page 3 Vol. 9 No. 5 ChristianOdyssey.org EDITORIAL By John Halford Here Be Dragons CONTENTS riving around the Bible Belt states in enigmatic enough without additional cul- 2 Editorial the USA, you will sometimes see a tural barriers. For example, Revelation 17: Dbumper sticker that proclaims, “The 3-4 describes “a woman sitting on a scarlet Bible says it. I believe it. That settles it.” Sim- beast that was covered with blasphemous 3 Scripture: God’s Gift ple and straightforward, right? names and had seven heads and ten horns. I wish it were. But in my nearly 50 years The woman was dressed in purple and 5 Thinking Out Loud of ministry, on all five continents, I have scarlet, and was glittering with gold, pre- learned that it is not always simple and cious stones and pearls.” At least those of If I Were God straightforward. I agree that if the Bible says us from a Judeo-Christian background have it, I should believe it and do it. The key is to no trouble recognizing this vision as ma- 6 Angry At God? Build a understand what it is the Bible is saying. levolent. But what is a Chinese person, who Bridge and Get Over It! Recently, while in Hong Kong, I vis- has grown up believing purple and scarlet ited with some Chinese friends that I have are the colors of celebration, and dragon- known for several decades. We were young like creatures are a symbol of good luck, to 7 The Parable of the Ugly Cat and idealistic when we first met, full of con- make of it? fidence that we understood “the truth.” Maybe these are extreme examples. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers in Bessemer

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; BLACKISH) -

SFSNNJ NEWSLETTER What’S Love Got to Do with It? February 2009 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday

SFSNNJ NEWSLETTER What’s Love Got To Do With It? February 2009 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 7p That's Science Fiction Teeth (2007) Hillsdale Library 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 8p Suspense Central 7p Whispers from 8p Drawing A Heart-Shaped Box by Beyond Joe Hill Crowd 8p Face the Fiction Borders Books, Guests: Peter Garden State Plaza New Moon Comics, Gutierrez & Rob Mall, Paramus, NJ Little Falls, NJ Hauschild Lutheran Church of the Redeemer, Ramsey,NJ 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 2:30p Fantasy 8p Films to Come Gamers Group 4 Star Film Reality's Edge Game Discussion Store Borders Books, Ramsey, NJ 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Infinite Chaos: 8p Themes of the 2p 8p Modern Masters Temnia Campaign Fantastic Star Doc by S.L. Viehl Ehrenfels Manor Borders Books, Rutherford, NJ New Moon Comics Ramsey Little Falls, NJ 29 1 February Face the Fiction “From Fan to Pro… and Back Again” How can simply watching too many movies as a fan lead to writing about them professionally… or starting a magazine… or a DVD label? And is there really such a big difference between the terms “fan” and “pro” as some would have us believe? For probably longer than they care to admit, Rob Hauschild and Peter Gutiérrez have been channeling their fannish tendencies into things like journalism, writing comics, media production, and teaching. In this slideshow-based talk, they’ll discuss their personal genre touchstones—not as classics deemed such by “experts” but as pop culture items that have inspired them and, in many cases, probably you as well. -

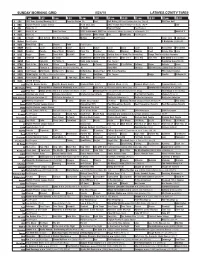

Sunday Morning Grid 5/24/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/24/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Bull Riding PBR Last Cowboy Standing. (Taped) PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC English Premier League Soccer Prem Goal Zone 2015 French Open Tennis First Round. (N) Å Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å Indy Pre-Race 2015 Indianapolis 500 From Indianapolis Motor Speedway in Indianapolis. (N) World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program 3 Backyards (2010) (R) 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Golden State of Mind: The Storytelling Things That Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Client ››› (1994) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Al Punto (N) Hotel Todo Incluido Paid Program República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Monaco Grand Prix. -

Epic Alice: Lewis Carroll and the Homeric Tradition

EPIC ALICE: LEWIS CARROLL AND THE HOMERIC TRADITION A Thesis by ALYSSA CASWELL MIMBS Submitted to the Graduate School Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2012 Department of English EPIC ALICE: LEWIS CARROLL AND THE HOMERIC TRADITION A Thesis by ALYSSA CASWELL MIMBS May 2012 APPROVED BY: ____________________________________ Dr. Jill Ehnenn Chairperson, Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Dr. William Atkinson Member, Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Dr. Alexander Pitofsky Member, Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Dr. James Fogelquist Chairperson, Department of English ____________________________________ Dr. Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Research and Graduate Studies Copyright by Alyssa Caswell Mimbs 2012 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT EPIC ALICE: LEWIS CARROLL AND THE HOMERIC TRADITION. (May 2012) Alyssa Caswell Mimbs, B.A., Appalachian State University M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Jill Ehnenn The purpose of this project was to reveal Lewis Carroll’s famous children’s novels Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There to be an attempt by the author to write a Victorian mock-heroic epic, one that is based largely on Homer’s Odyssey. Using a great deal of documented biographical information, it is evident that Carroll had more than just the expected education with Classical studies. By reading the two Alice novels as one story and setting them in comparison to Homer’s Odyssey, it is possible to find a great deal of similarities between the experiences of the two heroes and various characters throughout each narrative. Further exploration reveals that Carroll’s works include many structural techniques that support a poetic or oral telling of the story and all of the dominant themes that appear are also significant in the Odyssey.