The Effects of Non-Standard Forms of Employment on Worker Health and Safety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hearing Conservation Program

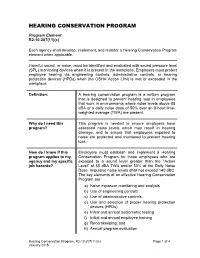

HEARING CONSERVATION PROGRAM Program Element R2-10-207(11)(c) Each agency shall develop, implement, and monitor a Hearing Conservation Program element when applicable. Harmful sound, or noise, must be identified and evaluated with sound pressure level (SPL) monitoring devices when it is present in the workplace. Employers must protect employee hearing via engineering controls, administrative controls, or hearing protection devices (HPDs) when the OSHA Action Limit is met or exceeded in the workplace. Definition: A hearing conservation program is a written program that is designed to prevent hearing loss in employees that work in environments where noise levels above 85 dBA or a daily noise dose of 50% over an 8-hour time- weighted average (TWA) are present. Why do I need this This program is needed to ensure employers have program? assessed noise levels which may result in hearing damage, and to ensure that employees exposed to noise are protected and monitored to prevent hearing loss. How do I know if this Employers must establish and implement a Hearing program applies to my Conservation Program for those employees who are agency and my specific exposed to a sound level greater than the “Action job hazards? Level” of 85 dBA TWA and/or 50% of the Daily Noise Dose. Impulsive noise levels shall not exceed 140 dBC. The key elements of an effective Hearing Conservation Program are: a) Noise exposure monitoring and analysis b) Use of engineering controls c) Use of administrative controls d) Use and selection of proper hearing protection devices (HPDs) e) Initial and annual audiometric testing f) Initial and annual employee training g) Recordkeeping; and h) Annual program evaluation Hearing Conservation Program, R2-10-207(11)(c) Page 1 of 4 January 2015 What are the minimum There are five OSHA required Hearing Conservation required elements and/ Program elements: or best practices for a Hearing Conservation 1. -

Temporary Employment in Stanford and Silicon Valley

Temporary Employment in Stanford and Silicon Valley Working Partnerships USA Service Employees International Union Local 715 June 2003 Table of Contents Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………….1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..5 Temporary Employment in Silicon Valley: Costs and Benefits…………………………………..8 Profile of the Silicon Valley Temporary Industry.………………………………………..8 Benefits of Temporary Employment…………………………………………………….10 Costs of Temporary Employment………………………………………………………..11 The Future of Temporary Workers in Silicon Valley …………………………………...16 Findings of Stanford Temporary Worker Survey ……………………………………………….17 Survey Methodology……………………………………………………………………..17 Survey Results…………………………………………………………………………...18 Survey Analysis: Implications for Stanford and Silicon Valley…………………………………25 Who are the Temporary Workers?……………………………………………………….25 Is Temp Work Really Temporary?………………………………………………………26 How Children and Families are Affected………………………………………………..27 The Cost to the Public Sector…………………………………………………………….29 Solutions and Best Practices for Ending Abuse…………………………………………………32 Conclusion and Recommendations………………………………………………………………38 Appendix A: Statement of Principles List of Figures and Tables Table 1.1: Largest Temporary Placement Agencies in Silicon Valley (2001)………………….8 Table 1.2: Growth of Temporary Employment in Santa Clara County, 1984-2000……………9 Table 1.3: Top 20 Occupations Within the Personnel Supply Services Industry, Santa Clara County, 1999……………………………………………………………………………………10 Table 1.4: Median Usual Weekly Earnings -

New Labour Hire Licensing Laws in Australia

Licence to Skill: New Labour Hire Licensing Laws in Australia For the first time, Australia is set to have three A “labour hire provider” is broadly defined and includes a person or business that supplies workers to do work for another person, states operating under three different mandatory regardless of how the activity might be described. The application is labour hire licensing schemes, which will broadly extremely broad and the regulations, which are purported to exclude impact the recruitment industry as well as the certain arrangements, are yet to be published. businesses that engage them. There are significant penalties for non-compliance. For example, operating without a licence will incur a maximum penalty of The schemes currently operating throughout Australia are not AU$130,439.10 for an individual or three years’ imprisonment and generally directed towards labour hire providers, and a number AU$378,450 for a corporation. The same penalties will also apply to expressly exclude labour hire. The recent push towards increased persons that enter into arrangements with unlicensed providers. regulation and extensive scrutiny was triggered by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Four Corners program, “Slaving Away”, Whilst the licence application and annual renewal fees will be in May 2015, which exposed exploitation of mostly migrant workers structured according to the size of a business, it is not yet clear through unscrupulous labour hire companies operating on farms and which companies would be classified as either a small, medium or in factories around the country. large provider. In response to public outcry, federal and (some) state governments In applying for a licence, labour hire providers (including a company’s commissioned inquiries (which are at varying levels of completion) executive officers) must satisfy a broad and subjective “fit and into such exploitation and misconduct. -

PLANNING AGREEMENT for Use by Employers and USF School of Social Work Students

School of Social Work BSW Field Program FIELD PRACTICUM PLANNING AGREEMENT For use by Employers and USF School of Social Work Students The purpose of this agreement is to encourage information sharing and commitment by all parties involved in planning for the educational success of (employee/student name) and (agency name). The employee is enrolling in the USF School of Social Work to pursue a degree in social work and will be required as a part of that enrollment to complete a field internship. Standards for this internship have been approved by our accrediting body, the Council on Social Work Education and have very clear goals and expectations. For a student to be successful in this endeavor, it is beneficial if each person involved understands the expectations of each of the others. For that purpose, we have created this agreement and the attachments for agencies and employee/students to assist in explaining the expectations of USF School of Social Work Field Program. We are aware this educational effort requires flexibility and planning of agencies and supervisors but believe you will find the overall functioning of your employee to improve during this same period as knowledge and skills are enhanced. Thank you for your assistance and we look forward to working with you. ____________________________________________________________________________ To be completed by employee/student: BSW Generalist (460 hours) or MSW Clinical Internship (900 hours) Total semesters in internship: Hours per semester of internship: Starting date of Internship: -

Consultation on the Operation of the Gangmasters Licensing (Exclusions) Regulations 2006 7

DEF-PB13107_OpGangmsts 10/7/08 10:33 Page 1 communisis The leading print partner C M www.defra.gov.uk Y K JOB LOCATION: PRINERGY 1 DISCLAIMER APPROVER The accuracy and the content of this file is the responsibility of the Approver. Please authorise approval only if you wish to proceed to print. Communisis PMS cannot accept liability for errors once the file has been printed. PRINTER This colour bar is produced manually all end users must check final separations to verify Consultation on the colours before printing. operation of the Gangmasters Licensing (Exclusions) Regulations 2006 July 2008 DEF-PB13107_OpGangmsts 10/7/08 10:33 Page 2 Consu Summ Backg Discu Propo D S S S Quas Supp Pea v Fores Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Nobel House What 17 Smith Square Anne London SW1P 3JR Telephone 020 7238 6000 T Website: www.defra.gov.uk Anne © Crown copyright 2008 A Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design rests with the Crown. Anne This publication (excluding the royal arms and departmental logos) may be reused free of charge Q in any format or medium provided that it is reused accurately and not used in a misleading Anne context. The material must be acknowledged as crown copyright and the title of the publication specified. P Information about this publication and further copies are available from: Anne L Gangmasters, Employment and Tenancies Team Area 7E, Millbank c/o Nobel House Defra 17 Smith Square London SW1P 3JR Email: [email protected] Tel: 020 7238 5702 This document is available on the Defra -

Understanding Nonstandard Work Arrangements: Using Research to Inform Practice

SHRM-SIOP Science of HR Series Understanding Nonstandard Work Arrangements: Using Research to Inform Practice Elizabeth George and Prithviraj Chattopadhyay Business School University of Auckland Copyright 2017 Society for Human Resource Management and Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of any agency of the U.S. government nor are they to be construed as legal advice. Elizabeth George is a professor of management in the Graduate School of Management at the University of Auckland. She has a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin and has worked in universities in the United States, Australia and Hong Kong. Her research interests include nonstandard work arrangements and inequality in the workplace. Prithviraj Chattopadhyay is a professor of management in the Management and International Business Department at the University of Auckland. He received his Ph.D. in organization science from the University of Texas at Austin. His research interests include diversity and demographic dissimilarity in organizations and nonstandard work arrangements. He has taught at universities in the United States, Australia and Hong Kong. 1 ABSTRACT This paper provides a literature review on nonstandard work arrangements with a goal of answering four key questions: (1) what are nonstandard work arrangements and how prevalent are they; (2) why do organizations have these arrangements; (3) what challenges do organizations that adopt these work arrangements face; and (4) how can organizations deal with these challenges? Nonstandard workers tend to be defined as those who are associated with organizations for a limited duration of time (e.g., temporary workers), work at a distance from the organization (e.g., remote workers) or are administratively distant from the organization (e.g., third-party contract workers). -

Organizational Behavior Seventh Edition

PRINT Organizational Behavior Seventh Edition John R. Schermerhorn, Jr. Ohio University James G. Hunt Texas Tech University Richard N. Osborn Wayne State University ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR 7TH edition Copyright 2002 © John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a data base retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 0-471-22819-2 (ebook) 0-471-42063-8 (print version) Brief Contents SECTION ONE 1 Management Challenges of High Performance SECTION FOUR 171 Organizations 81 Organizational Behavior Today 3 Illustrative Case: Creating a High Performance Power 173 Learning About Organizational Behavior 5 Organization 84 Empowerment 181 Organizations as Work Settings 7 Groups in Organizations 87 Organizational Politics 183 Organizational Behavior and Management 9 Stages of Group Development 90 Political Action and the Manager 186 Ethics and Organizational Behavior 12 Input Foundations of Group Effectiveness 92 The Nature of Communication 190 Workforce Diversity 15 Group and Intergroup Dynamics 95 Essentials of Interpersonal Communication Demographic Differences 17 Decision Making in Groups 96 192 Aptitude and Ability 18 High Performance Teams 100 Communication Barriers 195 Personality 19 Team Building 103 Organizational Communication 197 Personality Traits and Classifications 21 Improving Team Processes 105 -

The Value of a Contingent Workforce: Your Organization’S Outsource Recruiting Strategy

THE VALUE OF A CONTINGENT WORKFORCE: YOUR ORGANIZATION’S OUTSOURCE RECRUITING STRATEGY Your nonprofit is only as good as its people, so it’s imperative that you staff your organization for success. But staffing can be a challenge, especially in the face of your nonprofit or trade association’s ever-changing budgets, goals and needs. There are times when bringing on additional full-time employees isn’t the best way to fulfill your nonprofit’s goals. For example, you may have a seasonal or short-term project for which you need assistance, or a very specialized skillset gap you need to fill on a part-time basis. In these instances, your organization could benefit from utilizing contingent talent. What is a contingent workforce? How can it impact your nonprofit and the sector at large? This piece will explore: • The rise of the contingent workforce in both nonprofit and for-profit organizations; • The reasons for this shift in the job market; • The benefits of developing a contingent workforce at your organization; • And the steps you can take to successfully tap into the value of a contingent workforce. WHAT IS THE CONTINGENT WORKFORCE? A contingent worker is defined as a person who works for a company in an arrangement that is different from what was traditionally considered “standard” full-time employment. Contingent employees may work on a non-permanent or part-time basis. Examples of contingent workers include freelancers, independent contractors or consultants and temporary staff. Here are some of the most common types of contingent workers that nonprofits utilize, along with definitions of each:. -

422 PART 227—OCCUPATIONAL NOISE EXPOSURE Subpart A—General

Pt. 227 49 CFR Ch. II (10–1–20 Edition) by the BLS. The wage component is weight- 227.15 Information collection. ed by 40% and the equipment component by 60%. Subpart B—Occupational Noise Exposure 2. For the wage component, the average of for Railroad Operating Employees the data from Form A—STB Wage Statistics for Group No. 300 (Maintenance of Way and 227.101 Scope and applicability. Structures) and Group No. 400 (Maintenance 227.103 Noise monitoring program. of Equipment and Stores) employees is used. 227.105 Protection of employees. 3. For the equipment component, 227.107 Hearing conservation program. LABSTAT Series Report, Producer Price 227.109 Audiometric testing program. Index (PPI) Series WPU 144 for Railroad 227.111 Audiometric test requirements. Equipment is used. 227.113 Noise operational controls. 4. In the month of October, second-quarter 227.115 Hearing protectors. wage data are obtained from the STB. For 227.117 Hearing protector attenuation. equipment costs, the corresponding BLS rail- 227.119 Training program. road equipment indices for the second quar- 227.121 Recordkeeping. ter are obtained. As the equipment index is APPENDIX A TO PART 227—NOISE EXPOSURE reported monthly rather than quarterly, the COMPUTATION average for the months of April, May and APPENDIX B TO PART 227—METHODS FOR ESTI- June is used for the threshold calculation. 5. The wage data are reported in terms of MATING THE ADEQUACY OF HEARING PRO- dollars earned per hour, while the equipment TECTOR ATTENUATION cost data are indexed to a base year of 1982. APPENDIX C TO PART 227—AUDIOMETRIC BASE- 6. -

Job Satisfaction and Mental Health of Temporary Agency Workers in Europe: a Systematic Review and Re

www.ssoar.info Job satisfaction and mental health of temporary agency workers in Europe: a systematic review and research agenda Hünefeld, Lena; Gerstenberg, Susanne; Hüffmeier, Joachim Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Hünefeld, L., Gerstenberg, S., & Hüffmeier, J. (2020). Job satisfaction and mental health of temporary agency workers in Europe: a systematic review and research agenda. Work & Stress, 34(1), 82-110. https:// doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2019.1567619 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-74570-7 WORK & STRESS 2020, VOL. 34, NO. 1, 82–110 https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2019.1567619 Job satisfaction and mental health of temporary agency workers in Europe: a systematic review and research agenda Lena Hünefelda, Susanne Gerstenbergb and Joachim Hüffmeierc aFederal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (BAuA), Dortmund, Germany; bHochschule Bremen, City University of Applied Sciences, Bremen, Germany; cInstitute of Psychology, TU Dortmund University, Dortmund, Germany ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The current systematic literature review aimed to analyse the Received 7 June 2017 associations between temporary agency work (TAW), job Accepted 29 November 2018 satisfaction, and mental health in Europe, as well as to outline a KEYWORDS future research agenda. -

Tinnitus Characteristics at High-And Low-Risk Occupations from Occupational Noise Exposure Standpoint

PERSPECTIVE DOI: 10.5935/0946-5448.20210016 International Tinnitus Journal. 2021;25(1):87-93 Tinnitus characteristics at high-and low-risk occupations from occupational noise exposure standpoint Mehdi Asghari ABSTRACT Introduction: The aim of the present study was to compare tinnitus characteristics in high- and low-risk occupations from the occupational noise exposure standpoint, considering demographic data, hearing loss and concomitant diseases. Methods: Demographic data, characteristics of tinnitus, hearing and concomitant diseases were recorded in the questionnaires. Their pure tone air conduction thresholds were determined using a double-channel diagnostic Audiometer and the Bone Conduction was assessed using a B-71 bone vibrator. Results: Totally, 6.3% subjects (6.8% high-risk group and 5.6% low-risk group) had subjective tinnitus, mainly as whistling sound. In the high-risk group, tinnitus was mainly left-sided (41.18%) and hearing loss was mild. Bilateral tinnitus (52.63%) and slight hearing loss were observed predominantly in the low-risk group. Conclusions: The study showed higher incidence of tinnitus in high-risk professions regarding with occupational noise exposure. Keywords: Tinnitus; Loudness; Hearing loss; Noise exposure; High-risk occupations. 1Department of Medical Sciences, Arak University, Iran *Send correspondence to: Mehdi Asghari Department of Medical Sciences, Arak University, Iran. E-mail: [email protected], Phone: +81302040753 Paper submitted on February 07, 2021; and Accepted on April 18, 2021 87 International Tinnitus Journal, Vol. 25, No 1 (2021) www.tinnitusjournal.com INTRODUCTION 20 to 60 years referred to XXX Occupational Medicine Centers in 2018, Arak, Iran. Inclusion criteria included Tinnitus is a sound sensation in the ears or head in the age ≥18, at least a fifth grade education, wok experience absence of an external auditory or electrical source. -

ELE-The Case for Labour Hire-Making the Most of An

The Case For Labour Hire MAKING THE MOST OF AN OPPORTUNITY “I was seeing first-hand how labour hire was helping all types of businesses succeed, whether they were small one-man operations or large corporates employing hundreds of people.” WORDS BY BRENT MULHOLLAND Food Manufacturing I have been employed in what is known as Processing the ‘labour hire industry’ for the best part of 16 years. Prior to working in the labour Transportation Packaging hire space, my first leadership role was as Production Manager for one of Firth Industries subsidiaries (Dricon Bagging) in 1990, just Security Warehousing over 30 years ago. From there I moved into ELE GROUP operations management with ADT Securitas PROVIDES and developed a solid career in the security Production ACCESS TO NEW Horticulture industry for over a decade. In the early part INDUSTRIES of 2000, I worked with Tyco Services, who Civil Construction at that time owned Armourguard in New Construction Zealand where I was the National Business Development Manager. Mining Infrastructure SO, WHAT DOES ALL OF THIS MEAN? Information Logistics Well, up to the point of joining the labour hire/ Technology recruitment industry in 2004, I had no idea that there existed such an industry anywhere near the scale I would soon start to appreciate track of the number of times our plant was felt like there could be a win-win for all – one that was clearly developing momentum shut down for lengthy periods due to age and stakeholders – including their members with businesses of all shapes and sizes. associated engineering failures, maintenance who I had hoped, may one day be our or product line switches – and the staff would workers.