From the Chair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Livestock Regulations

NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA LIVESTOCK REGULATIONS As in force at 1 January 2015 Table of provisions Part 1 Preliminary matters 1 Citation ............................................................................................ 1 2 Commencement .............................................................................. 1 3 Definitions ........................................................................................ 1 4 Notices and applications .................................................................. 3 Part 2 Identification and registration of livestock, properties and other things Division 1 Registration of brands and earmarks 5 Livestock for which 3-letter brands may be registered ..................... 3 6 Fees ................................................................................................ 3 7 Application for registration of 3-letter brand ..................................... 4 8 Decision relating to registration of brand or earmark ....................... 4 9 Decision relating to transfer of registered 3-letter brand .................. 5 10 Registration ..................................................................................... 5 11 Certificate of registration .................................................................. 6 12 Requirement to give impression of brand ........................................ 6 13 Requirement to notify change of address ........................................ 7 14 Decision to cancel registration of 3-letter brand .............................. -

Texas Direct Farm Business Guide

TEXAS DIRECT FARM BUSINESS GUIDE MICHAELA TARR CHARLES CUNNINGHAM RUSTY W. RUMLEY 1 Texas Direct Farm Business Guide Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 6 I. Using This Guide ............................................................................................................. 7 II. Overview of Administrative Agencies ......................................................................... 8 III. The Food and Drug Administration’s Food Code ...................................................... 10 IV. Texas State Department of Health .............................................................................. 10 Section 1: Farming Operations .................................................................................................... 13 Chapter 1: Structuring the Business .......................................................................................... 14 I. Planning the Direct Farm Business ................................................................................ 14 II. Choosing a Business Entity ........................................................................................ 16 III. Checklist ..................................................................................................................... 23 Chapter 2 - Setting up the Direct Farm Business:..................................................................... 24 I. Siting ............................................................................................................................. -

Sixth Amended Hays County Animal Control Ordinance

SIXTH AMENDED HAYS COUNTY ANIMAL CONTROL ORDINANCE NO. 32190 This Sixth Amended Hays County Animal Control Ordinance is made this the 24th day of January, 2017, by the Hays County Commissioners Court, which, having duly considered the need for immediate modification of the existing Animal Control Ordinance, adopts this Sixth Amended Animal Control Ordinance effective upon passage by a majority vote. AN ORDINANCE OF THE COMMISSIONERS COURT OF HAYS COUNTY, TEXAS, TO ESTABLISH A RABIES CONTROL PROGRAM, DESIGNATE A LOCAL ANIMAL CONTROL AUTHORITY, REQUIRE THE LICENSING AND RESTRAINT OF CERTAIN ANIMALS, MANDATE THE IDENTIFICATION OF LIVESTOCK, REGULATE DANGEROUS DOGS AND OTHER DANGEROUS ANIMALS, DECLARE A PUBLIC NUISANCE AND PROVIDE PENALTIES PURSUANT TO CHAPTERS 822 AND 826 OF THE TEXAS HEALTH & SAFETY CODE, CHAPTER 802 OF THE TEXAS OCCUPATIONS CODE AND CHAPTERS 142-144 OF THE TEXAS AGRICULTURAL CODES. WHEREAS, the Commissioners Court of Hays County is authorized by Chapter 822 of the Texas Health & Safety Code to enact a local ordinance to regulate the registration and restraint of animals; and WHEREAS, the Commissioners Court of Hays County is authorized by Chapter 826 of the Texas Health & Safety Code to enact a local ordinance to require rabies vaccinations and other measures as a means to prevent the dangerous spread of rabies; and WHEREAS, the Commissioners Court of Hays County is authorized by Chapter 142,143 and 144 of the Texas Agricultural Code to enact a local ordinance to prohibit livestock from running at large, mandate livestock -

Chapter 329. Animals Act 1952. Certified On

Chapter 329. Animals Act 1952. Certified on: / /20 . INDEPENDENT STATE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA. Chapter 329. Animals Act 1952. ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS. PART I – PRELIMINARY. 1. Interpretation. “brand” “branded stock” “the Brands Directory” “cattle” “cattle earmark” “the Chief Inspector of Brands” “court” “crop” “cruelty” “distinctive brand” “earmark” “hide” “horse” “horse and cattle brand” “Inspector of Brands” “official brand” “official mark” “owner” “person” “pliers” “poundkeeper” “the Register” “registered” “the Registrar” “the regulations” “residence” “saleyard” “sheep brand” “sheep earmark” “spay mark” “stock” “this Act” PART II – ANIMAL TRESPASS. 2. Interpretation of Part II. “animal” 3. Straying animals. 4. Confinement of stock. 5. Complaint about unconfined animals. 6. Orders to confine animals. 7. Service of order. 8. Extension of time in order. 9. Forfeiture of animals not confined. 10. Using animals to make other person liable. PART III – POUNDS. 11. Interpretation of Part III. “animal” 12. Application of Part III. 13. Pounds. 14. Poundkeepers. 15. Pound book. 16. Fees. 17. Table of fees. 18. Impounding. 19. Impounding at nearest pound. 20. Impounded animals. 21. Recovery of impounded animals. 22. Posting of notice of impounding. 23. Sale by auction of impounded animals. 24. Destruction of unsold animals. 25. Proceeds of sale. 26. Allowing animals to stray. PART IV – STOCK BRANDS. Division 1 – Preliminary. 27. Interpretation of Part IV. “stock” “vendor” Division 2 – Administration. 28. Chief Inspector of Brands. 29. Registrar and Deputy Registrars of Brands. 30. Inspectors of Brands. 31. Powers of inspectors. Division 3 – Registration. – ii – 32. Application for registration. 33. Registration. 34. Certificate of registration. 35. Register of Brands and Earmarks. 36. -

Order Form Compiled and Edited Tennessee Laws Pertaining to Animals 2010

Copyright © 2010 The University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine Publication # R181731029-00-002-11 2 Table of Contents +2(1(4/.' !" !!" '''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''// +2(3(0.6'%" ''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''// +2(5(/.4'! $ '''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''// +2(5(//3' !!!" '''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''/0 +3(/(/0.' $!"! !% ''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''/0 +3(7(//.'$''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''/0 +4(0(0./'$ '''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''/0 +4(/7(/./'$ '''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''/0 +4(32(/13'$! "! ! !"!'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''/1 +5(3/(/2./'!! ''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''/2 +5(41(/./' "#! )!!!" !''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''/2 +5(41(0./' !!&!!!!( " " ) ''''''/2 +5(6/(0.5' $ %'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''/3 +6(3.(/.1'%!! (( !!(( !%((!'/3 +7(6(1.5'" !(( ((#! (( !!!!%(( (( "! ((! (( '''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''/3 +/0(2(5.0'! ''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''''/3 -

A New Direction in Food Labeling and Animal Welfare

GIVING SLAUGHTERHOUSES GLASS WALLS: A NEW DIRECTION IN FOOD LABELING AND ANIMAL WELFARE By Zak Franklin* Modern industrial animal agriculture and consumer purchasingpatterns do not match consumers' moral preferences regarding animal welfare. Cur- rent production methods inflict a great deal of harm on animals despite widespread consumer preference for meat, dairy, and eggs that come from humanely treated animals. Judging by the premium pricing and market shares of food products with moral or special labels (e.g., 'cage-free," 'free range,' and 'organic'), many consumers are willing to pay more for less harmful products, but they are unable to determine which products match this preference. The labels placed on animal products, and the insufficient government oversight of these labels, are significantfactors in consumer ig- norance because producers are allowed to use misleading labels and thwart consumers from aligning their preferences with their purchases. Producers are allowed to label their goods as friendly to animals or the environment without taking action to conform to those claims. Meanwhile, producers who do invest resources into more humane or environmentally-consciousproduc- tion methods are competing with companies that do not make similar ex- penditures. Those companies can sell their products at a lower price without sacrificingprofits, which prices-out producers who do invest resources. This Article proposes a new labeling regime in which animal products feature labels that adequately inform consumers of agriculturalpractices so that consumers can match their purchases with their moral preferences. In this proposed scheme, animal products would contain a label that concisely and objectively informs consumers what practices went into the making of that item. -

States' Animal Cruelty Statutes

States’ Animal Cruelty Statutes: Ohio This material is based upon work supported by the National Agricultural Library, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture A National Agricultural Law Center Research Publication States’ Animal Cruelty Statutes: Ohio Current through File 60 of the 133rd General Assembly (2019-2020). 959.01 Abandoning animals No owner or keeper of a dog, cat, or other domestic animal, shall abandon such animal. 959.02 Injuring animals No person shall maliciously, or willfully, and without the consent of the owner, kill or injure a horse, mare, foal, filly, jack, mule, sheep, goat, cow, steer, bull, heifer, ass, ox, swine, dog, cat, or other domestic animal that is the property of another. This section does not apply to a licensed veterinarian acting in an official capacity. 959.03 Poisoning animals No person shall maliciously, or willfully and without the consent of the owner, administer poison, except a licensed veterinarian acting in such capacity, to a horse, mare, foal, filly, jack, mule, sheep, goat, cow, steer, bull, heifer, ass, ox, swine, dog, cat, poultry, or any other domestic animal that is the property of another; and no person shall, willfully and without the consent of the owner, place any poisoned food where it may be easily found and eaten by any of such animals, either upon his own lands or the lands of another. 959.04 Trespassing animals Sections 959.02 and 959.03 of the Revised Code do not extend to a person killing or injuring an animal or attempting to do so while endeavoring to prevent it from trespassing upon his enclosure, or while it is so trespassing, or while driving it away from his premises; provided within fifteen days thereafter, payment is made for damages done to such animal by such killing or injuring, less the actual amount of damage done by such animal while so trespassing, or a sufficient sum of money is deposited with the nearest judge of a county court or judge of a municipal court having jurisdiction within such time to cover such damages. -

A Sustainable Charge on Meat

A sustainability charge on meat A sustainability charge on meat Authors: Robert Vergeer, Jaime Rozema, Ingrid Odegard and Pelle Sinke With contributions from: Geraldo Vidigal (UVA, legal aspects), Frits van der Schans (CLM, side-effects of climate measures and financial incentives for herd reduction) Delft, CE Delft, January 2020 Publication code: 20.190106.010 Meat / Consumption / Policy instruments / Pricing / Costs / Environment / Economic factors / Social factors This study was commissioned by: True Animal Protein Price Coalition (TAPP Coalition), Dutch Vegetarian Society, Proveg International, Dutch Animal Coalition, Triodos Foundation All CE Delft’s public publications are available at www.cedelft.eu For more information on this study plrease contact the project leader Robert Vergeer (CE Delft) © Copyright, CE Delft, Delft CE Delft Committed to the Environment Through its independent research and consultancy work CE Delft is helping build a sustainable world. In the fields of energy, transport and resources our expertise is leading-edge. With our wealth of know-how on technologies, policies and economic issues we support government agencies, NGOs and industries in pursuit of structural change. For 40 years now, the skills and enthusiasm of CE Delft’s staff have been devoted to achieving this mission. 1 190106 - A sustainability charge on meat – January 2020 Contents Summary 4 1 Introduction 6 1.1 Background 6 1.2 Methodology in brief 6 1.3 Project scope 7 1.4 Report structure 8 2 Sustainability charge design 9 2.1 External Costs -

LCARA Cover.Pub

LANE COUNTY - Oregon - Animal Regulation Advisory Task Force Findings and Recommendations FINAL REPORT Adopted by the Task Force November 12, 2003 LANE COUNTY’S Animal Regulation Advisory Task Force Findings and Recommendations FINAL REPORT Adopted by the Task Force on November 12, 2003 Lane County Government 125 East 8th Avenue Eugene, Oregon 97401 (541) 682-4203 http://www.co.lane.or.us/ 2 TASK FORCE MEMBERS Scott Bartlett (Chair) Member of Public William A. Fleenor, Ph.D. (Vice Chair) Member of Public Hon. Cynthia Sinclair Judicial Liaison Roberta L. Boyden, D.V.M. Member of Public Mike Wellington Animal Regulation Program Manager Christopher Horton Member of Public Carol Pomes City of Eugene Liaison Diana Robertson Animal Welfare Alliance Liaison Janetta Overholser Humane Society Liaison Richard Lewis City of Springfield Liaison Sandra Smalley, D.V.M. Lane County Veterinary Medical Association Liaison 3 ADDITIONAL CONTRIBUTORS Task Force Research Associate: Ross Alan Owen Department of Public Policy and Management University of Oregon, Eugene Lane County Staff & Support David Suchart Director, Management Services Lane County Government Christine Moody Executive Assistant, Management Services Lane County Government Former Task Force Members: Eugene M. Luks, Ph.D. Member of Public Mary Whitlock, D.V.M. Lane County Veterinary Medical Association Liaison 4 “The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated” - Mahatma Gandhi - “Anyone who has accustomed himself to regard the life of any living -

Animal Law in South Carolina Piecing It All Together

A COMPREHENSIVE FREE LEGAL GUIDE Animal Law in South Carolina Piecing It All Together BY STEPHAN FUTERAL, ESQUIRE COPYRIGHT © FUTERAL & NELSON, LLC, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Copyright Notice Animal in South Carolina - Piecing It All Together A Comprehensive Free Legal Guide Stephan V. Futeral, Esq. © 2015 Futeral & Nelson, LLC, All Rights Reserved Self Published www.charlestonlaw.net ________________________ This book contains material protected under International and Federal Copyright Laws and Treaties. Any unauthorized reprint or use of this material is prohibited. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without express written permission from the author/publisher. i Foreword My wife Kelsey and I have 4 dogs, all of which are rescues, and three of which are pet therapy dogs. Kelsey is the secretary of Pet Therapy, Inc., which is a national organization with over 10,000 members and growing. When people ask me why we have four dogs, I tell them it’s because we don’t want five! All kidding aside, we have a passion for rescuing dogs. On weekends, we take our therapy dogs to visit with the elderly at local senior centers and assisted-living facilities. I can’t begin to describe to you how rewarding the experience is for us, for our dogs, and for the people with whom we visit. For those of us who own pets, they’re like members of our family. According to a Harris Poll conducted in 2011, more than three in five Americans (62%) have a pet. -

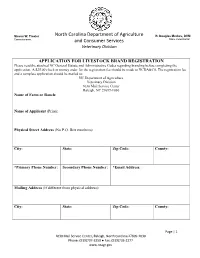

North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services As He Deems Necessary to Implement This Article

Steven W. Troxler North Carolina Department of Agriculture R. Douglas Meckes, DVM Commissioner and Consumer Services State Veterinarian Veterinary Division APPLICATION FOR LIVESTOCK BRAND REGISTRATION Please read the attached NC General Statute and Administrative Codes regarding branding before completing the application. A $25.00 check or money order for the registration fee should be made to NCDA&CS. The registration fee and a complete application should be mailed to: NC Department of Agriculture Veterinary Division 1030 Mail Service Center Raleigh, NC 27699-1030 Name of Farm or Ranch: Name of Applicant (Print): Physical Street Address (No P.O. Box numbers): City: State: Zip Code: County: *Primary Phone Number: Secondary Phone Number: *Email Address: Mailing Address (If different from physical address): City: State: Zip Code: County: Page | 1 1030 Mail Service Center, Raleigh, North Carolina 27699-1030 Phone: (919)707-3250 ● Fax: (919)733-2277 www.ncagr.gov Email a digital image of the brand you wish to register to: [email protected]. Alternatively, you may NEATLY draw your brand in the box provided below. Please refer to the attached Administrative Codes for brand design restrictions. (Drawing of Brand or Mark) Please give a full description of your brand: __________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Ilia Missing Livestock Bulletins

LIVESTOCK BULLETIN BUREAU OF LIVESTOCK IDENTIFICATION Edited By: State of California Corey M. Schimeck Department of Food & Agriculture NO: 19 - 11 Website: www.cdfa.ca.gov/ahfss/Livestock_ID March 15, 2019 Anyone with information regarding the following livestock, please contact the Bureau of Livestock Identification, 1220 ”N” Street, Sacramento, California 95814, (916) 900-5006, or the reporting Brand Inspector. John Suther, Branch Chief County of Origin:Nevada-29 Cattle Missing Report Date: 03/13/2019 Person/Entity: Donald Nachtegaehe City, ST & Zip Code: Grass Valley, CA 95949 Sorting CDFA, Location of Theft (City, County, State) Case No. & Livestock Description: 204-MS-00061 Report Date: 3/13/2019 County, ILIA Brand, Location & Earmarks Comments: 1 - Black, Steer, 11 Months, 600 # LH One Black Steer branded with Triple Bar over Quarter Circle on the Left Hip was Bulletin #: found missing from 19250 Fairview Dr in 19 - 11 Grass Valley, CA 95949. Animal was last seen on 11/13/2018. Inspector: Jill Jess-Burtschi, (209) 482-6510 Sale Date: County of Origin:Amador-03 Cattle Estray Report Date: Person/Entity: State of California City, ST & Zip Code: Sacramento, CA 95814 Sorting CDFA, Location of Theft (City, County, State) Case No. & Livestock Description: 204-HO-00060 Report Date: County, ILIA Brand, Location & Earmarks Comments: 1 - Black, Steer, 6 Months, 475# LH - Earmark Brought in as stray from Irish Hill Rd Ione, CA. Bulletin #: 1911 Inspector: Jill Jess-Burtschi, (209) 482-6510 Sale Date: Cattlemen's Livestock Market, Galt, CA Page 1 County of Origin:Kings-16 Cattle Held For P. O. O. - Sold Emergency Report Date: Person/Entity: Modesto Livestock Commision Company, Inc.