FINAL Mid Term Evaluation Report NGAT97

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The POWER of DELIVERY Is a Compilation of Selected Extempore Remarks, and the first of a Trilogy, by Governor Henry Seriake Dickson of Bayelsa State, Nigeria

DICKS The POWER of DELIVERY is a compilation of selected extempore remarks, and the first of a trilogy, by Governor Henry Seriake Dickson of Bayelsa State, Nigeria. ON In this book, the reader will encounter the robustness of Governor Dickson's DICKSON remarks delivered extempore with striking ability to inspire and engage its audience in a manner that is most compelling. Governor Dickson is an orator of a different hue. He speaks authoritatively with penetrating intellectual depth THE POWER OF typical of most great leaders in the world, both past and present. DELIVERY Restoration Leaps Forward GOVERNOR HENRY SERIAKE DICKSON A PROFILE THE POWER OF DELIVERY Governor Henry Seriake Dickson of Bayelsa State in Nigeria has, by his performance in office, underscored the critical role of leadership in strategic restructuring and effective governance. He has changed the face of development, sanitized the polity, and encouraged participatory governance. The emerging economic prosperity in Bayelsa is a product of vision and courage. Dickson, 48, is an exceptional leader whose foresight on the diversification of the state’s economy beyond oil and gas to focus more on tourism and agriculture holds great promise of economic boom. A lawyer, former Attorney-General of Bayelsa State and member of the National Executive Committee of the Nigerian Bar Association, he was elected to the House of Representatives in 2007 and re-elected in 2011, where he served as the Chairman, House Committee on Justice. His star was further on the rise when he was elected governor of Bayelsa State by popular acclamation later in 2012. He has been an agent of positive change, challenged the status quo and re-invented the architecture of Hon. -

Nigeria: Ending Unrest in the Niger Delta

NIGERIA: ENDING UNREST IN THE NIGER DELTA Africa Report N°135 – 5 December 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. FALTERING ATTEMPTS TO ADDRESS THE DELTA UNREST........................ 1 A. REACHING OUT TO THE MILITANTS?.....................................................................................1 B. PROBLEMATIC PEACE AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION COMMITTEES.........................................3 C. UNFULFILLED PROMISES.......................................................................................................4 III. THE RISING TOLL....................................................................................................... 7 A. CONTINUING VIOLENCE ........................................................................................................7 1. Attacks on expatriates and oil facilities .....................................................................7 2. Politicians, gangs and the Port Harcourt violence .....................................................7 3. The criminal hostage-taking industry ........................................................................8 B. REVENUE LOSS AND ECONOMIC DESTABILISATION ..............................................................9 C. EXPATRIATE AND INVESTMENT FLIGHT ..............................................................................10 IV. GOVERNMENT -

An Analysis of What Works and What Doesn't

Radicalisation and Deradicalisation in Nigeria: An Analysis of What Works and What Doesn’t Nasir Abubakar Daniya i Radicalisation and Deradicalisation in Nigeria: An Analysis of What Works and What Doesn’t. Nasir Abubakar Daniya Student Number: 13052246 A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of Requirements for award of: Professional Doctorate Degree in Policing Security and Community Safety London Metropolitan University Faculty of Social Science and Humanities March 2021 Thesis word count: 104, 482 ii Abstract Since Nigeria’s independence from Britain in 1960, the country has made some progress while also facing some significant socio-economic challenges. Despite being one of the largest producers of oil in the world, in 2018 and 2019, the Brooking Institution and World Poverty Clock respectively ranked Nigeria amongst top three countries with extreme poverty in the World. Muslims from the north and Christians from the south dominate the country; each part has its peculiar problem. There have been series of agitations by the militants from the south to break the country due to unfair treatments by the Nigerian government. They produced multiple violent groups that killed people and destroyed properties and oil facilities. In the North, an insurgent group called Boko Haram emerges in 2009; they advocated for the establishment of an Islamic state that started with warning that, western education is prohibited. Reports say the group caused death of around 100,000 and displaced over 2 million people. As such, Niger Delta Militancy and Boko Haram Insurgency have been major challenges being faced by Nigeria for about a decade. To address such challenges, the Nigerian government introduced separate counterinsurgency interventions called Presidential Amnesty Program (PAP) and Operation Safe Corridor (OSC) in 2009 and 2016 respectively, which are both aimed at curtailing Militancy and Insurgency respectively. -

Towards a New Type of Regime in Sub-Saharan Africa?

Towards a New Type of Regime in Sub-Saharan Africa? DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS BUT NO DEMOCRACY Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos cahiers & conférences travaux & recherches les études The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental and a non- profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. The Sub-Saharian Africa Program is supported by: Translated by: Henry Kenrick, in collaboration with the author © Droits exclusivement réservés – Ifri – Paris, 2010 ISBN: 978-2-86592-709-8 Ifri Ifri-Bruxelles 27 rue de la Procession Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – France 1000 Bruxelles – Belgique Tél. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 Tél. : +32 (0)2 238 51 10 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Internet Website : Ifri.org Summary Sub-Saharan African hopes of democratization raised by the end of the Cold War and the decline in the number of single party states are giving way to disillusionment. -

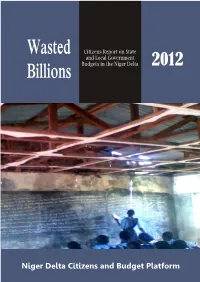

Wasted Billion Report

Wasted Citizens Report on State and Local Government Budgets in the Niger Delta 2012 Billions Niger Delta Citizens and Budget Platform Wasted Billions Citizens Report on State and Local Government Budgets in the Niger Delta Niger Delta Citizens and Budget Platform Copyright 2013 Social Development Integrated Centre (Social Action) All rights reserved ISBN: 978-8068-73-6 Published by: Niger Delta Citizens and Budget Platform Social Development Integrated Centre (Social Action) 33, Oromineke Layout, D -Line Port Harcourt, Nigeria Tel/Fax +234 84 765 413 www.citizensbudget.org Design and Layout: Jittuleegraphix Cover Photo by: Ken Henshaw/Social Action Wasted Billions Table of Contents List of Figure v List of Abbreviations vi Acknowledgments viii Executive Summary 1 Recommendations 5 Method and Score 7 Background 8 Akwa Ibom State 17 Bayelsa State 26 Delta State 37 Edo State 47 Rivers State 57 About NDCBP 72 iv Wasted Billions List of Figures Figure 1 Recurrent and Capital expenditure budget shares in the Akwa Ibom 2012 budget Figure 2 Internally generated revenue in Akwa Ibom 2012 compared to total budget Figure 3 Allocations to different sectors in the Akwa Ibom 2012 Budget Figure 4 Allocation to Education in the Akwa Ibom 2012 budget Figure 5 Allocation to Health in the Akwa Ibom 2012 Budget Figure 6 Allocation to food sufficiency related programs in the Akwa Ibom 2012 Budget Figure 7 Bayesla state budget 2007-2012 Figure 8 Distribution of Bayelsa state 2012 revenue source Figure 9 Bayelsa state recurrent and capital expenditure budget -

First Election Security Threat Assessment

SECURITY THREAT ASSESSMENT: TOWARDS 2015 ELECTIONS January – June 2013 edition With Support from the MacArthur Foundation Table of Contents I. Executive Summary II. Security Threat Assessment for North Central III. Security Threat Assessment for North East IV. Security Threat Assessment for North West V. Security Threat Assessment for South East VI. Security Threat Assessment for South South VII. Security Threat Assessment for South West Executive Summary Political Context The merger between the Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), Congress for Progressive Change (CPC), All Nigerian Peoples Party (ANPP) and other smaller parties, has provided an opportunity for opposition parties to align and challenge the dominance of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP). This however will also provide the backdrop for a keenly contested election in 2015. The zoning arrangement for the presidency is also a key issue that will define the face of the 2015 elections and possible security consequences. Across the six geopolitical zones, other factors will define the elections. These include the persisting state of insecurity from the insurgency and activities of militants and vigilante groups, the high stakes of election as a result of the availability of derivation revenues, the ethnic heterogeneity that makes elite consensus more difficult to attain, as well as the difficult environmental terrain that makes policing of elections a herculean task. Preparations for the Elections The political temperature across the country is heating up in preparation for the 2015 elections. While some state governors are up for re-election, most others are serving out their second terms. The implication is that most of the states are open for grab by either of the major parties and will therefore make the electoral contest fiercer in 2015 both within the political parties and in the general election. -

The Jonathan Presidency, by Abati, the Guardian, Dec. 17

The Jonathan Presidency By Reuben Abati Published by The Jonathan Presidency The Jonathan Presidency By Reuben Abati A review of the Goodluck Jonathan Presidency in Nigeria should provide significant insight into both his story and the larger Nigerian narrative. We consider this to be a necessary exercise as the country prepares for the next general elections and the Jonathan Presidency faces the certain fate of becoming lame-duck earlier than anticipated. The general impression about President Jonathan among Nigerians is that he is as his name suggests, a product of sheer luck. They say this because here is a President whose story as a politician began in 1998, and who within the space of ten years appears to have made the fastest stride from zero to “stardom” in Nigerian political history. Jonathan himself has had cause to declare that he is from a relatively unknown village called Otuoke in Bayelsa state; he claims he did not have shoes to wear to school, one of those children who ate rice only at Xmas. When his father died in February 2008, it was probably the first time that Otuoke would play host to the kind of quality crowd that showed up in the community. The beauty of the Jonathan story is to be found in its inspirational value, namely that the Nigerian dream could still take on the shape of phenomenal and transformational social mobility in spite of all the inequities in the land. With Jonathan’s emergence as the occupier of the highest office in the land, many Nigerians who had ordinarily given up on the country and the future felt imbued with renewed energy and hope. -

Politics with in Response to a Question Americans Came Here Through Know Their Foreign Allies Expenditure on Security

How police rescued two stolen children in Abia Pg. 7 @newsechonigeria @newsechonigeria @newsechonigeria ...Strong voice echoes the truth ISSN: 2736-0512 WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 16, 2020 VOL. 1 NO. 49 N150 Kidnapped Katsina students: Declare emergency Pg. 2 in North now – Air Cdr. Ochulor (rtd) Umahi budgets N123bn for 2021 fiscal year Pg. 13 The kidnap suspects Katsina abduction: Does Nigeria still have a president? Nigerians knock Buhari for preferring cows to human lives Pg. 3 Buhari Palliative: 8 die in Rivers stampede Pg. 7 Obiano flags off campaign to end Pg. 10 open defecation Wike Brace up for second wave of COVID-19, Enugu gov. charges NANTMP vows to fight fake herbalists in Imo Pg. 11 Pg. 11 Wednesday, December 16, 2020 the violence and killing, he Nigeria should have allies to said it is in the emergency support it to clear the Kidnapped Katsina students: Declare mass mobilization of able challenge and not enough to bodied men. It is not that the just procure military aircraft soldiers we have to call a spade or hard ware from America or emergency in North now - Ochulor by its name. Russia citing the manner By Afam Echi “The inability of Nigeria to spite of the huge budget are playing politics with In response to a question Americans came here through know their foreign allies expenditure on security. people's lives. I insist that there on the effectiveness of the new a neighboring state to rescue he former military outside Africa makes it more In his words, 'I don't should be mass mobilization strategy of mass mobilization its citizen quietly and without administrator of Delta difficult. -

The Judiciary and Nigeria's 2011 Elections

THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS CSJ CENTRE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE (CSJ) (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS Written by Eze Onyekpere Esq With Research Assistance from Kingsley Nnajiaka THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiii First Published in December 2012 By Centre for Social Justice Ltd by Guarantee (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) No 17, Flat 2, Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, P.O. Box 11418 Garki, Abuja Tel - 08127235995; 08055070909 Website: www.csj-ng.org ; Blog: http://csj-blog.org Email: [email protected] ISBN: 978-978-931-860-5 Centre for Social Justice THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiiiiii Table Of Contents List Of Acronyms vi Acknowledgement viii Forewords ix Chapter One: Introduction 1 1.0. Monitoring Election Petition Adjudication 1 1.1. Monitoring And Project Activities 2 1.2. The Report 3 Chapter Two: Legal And Political Background To The 2011 Elections 5 2.0. Background 5 2.1. Amendment Of The Constitution 7 2.2. A New Electoral Act 10 2.3. Registration Of Voters 15 a. Inadequate Capacity Building For The National Youth Service Corps Ad-Hoc Staff 16 b. Slowness Of The Direct Data Capture Machines 16 c. Theft Of Direct Digital Capture (DDC) Machines 16 d. Inadequate Electric Power Supply 16 e. The Use Of Former Polling Booths For The Voter Registration Exercise 16 f. Inadequate DDC Machine In Registration Centres 17 g. Double Registration 17 2.4. Political Party Primaries And Selection Of Candidates 17 a. Presidential Primaries 18 b. -

Democracy and the Hegemony of Corruption in Nigeria (1999-2017)

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 9 , No. 3, March, 2019, E-ISSN: 2222 -6990 © 2019 HRMARS Nigerian Conundrum: Democracy and the Hegemony of Corruption in Nigeria (1999-2017) Emmanuel Chimezie Eyisi To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i3/5673 DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i3/5673 Received: 21 Feb 2019, Revised: 08 March 2019, Accepted: 18 March 2019 Published Online: 21 March 2019 In-Text Citation: (Eyisi, 2019) To Cite this Article: Eyisi, E. C. (2019). Nigerian Conundrum: Democracy and the Hegemony of Corruption in Nigeria (1999-2017). International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(3), 251– 267. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 9, No. 3, 2019, Pg. 251 - 267 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 251 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 9 , No. 3, March, 2019, E-ISSN: 2222 -6990 © 2019 HRMARS Nigerian Conundrum: Democracy and the Hegemony of Corruption in Nigeria (1999-2017) Emmanuel Chimezie Eyisi (Ph.D) Department of Sociology/Psychology/Criminology, Faculty of Management and Social Sciences Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu-alike Ikwo, Ebonyi State. -

A Fight Between Law and Justice at the Supreme Court,The Tenure

A FIGHT BETWEEN LAW AND JUSTICE AT THE SUPREME COURT: THE TENURE ELONGATION CASE REVISITED 1* Introduction It was the late Justice Chukwudifu Oputa who once counselled judicial officers to ensure that they leaned on the side of justice in any case of conflict between law and justice. In his immortal words: “The judge should appreciate that in the final analysis the end of law is justice . He should therefore endeavour to see that the law and the justice of the individual case he is trying go hand in hand… To this end he should be advised that the spirit of justice does not reside in formalities, not in words, nor is the triumph of the administration of justice to be found in successfully picking a way between pitfalls of technicalities. He should know that all said and done, the law is, or ought to be, but a handmaid of justice, and inflexibility which is the most becoming robe of law often serves to render justice grotesque. In any ‘fight’ between law and justice the judge should ensure that justice prevails – that was the very reason for the emergence of equity in the administration of justice. The judge should always ask himself if his decision, though legally impeccable in the end achieved a fair result. ‘That may be law but definitely not justice’ is a sad commentary on any decision.” Oputa JSC. Undoubtedly, the Supreme Court would appear to have heeded this counsel of the one who once was part of the court in the case under review (Marwa & Anor. -

WORKABILITY of the NORMS of TRANSPARENCY and ACCOUNTABILITY AGAINST CORRUPTION in NIGERIA Simeon Igbinedion*

IGBINEDION: WORKABILITY OF THE NORMS OF ACCOUNTABILITY AND TRANSPARENCY AGAINST CORRUPTION 149 WORKABILITY OF THE NORMS OF TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY AGAINST CORRUPTION IN NIGERIA Simeon Igbinedion* ABSTRACT his paper discusses the workability of the existing norms of transpar- Tency and accountability in the battle against corruption in Nigeria. In- controvertibly, high level corruption pervades every nook and cranny of the country to the detriment of its citizens. Although anti-corruption norms exist in the Nigerian legal order, high profile corruption remains endemic, suggesting that the norms are unworkable. This paper argues that the unworkability of transparency and account- ability norms in Nigeria is largely attributable to the contradictions, incon- sistencies or deficiencies inherent therein. Consequently, the paper suggests ways of putting the norms to work against corruption in Nigeria. Keywords: Corruption, Governance, Sustainable Development * LL.B, B.L, LL.M, Ph.D: Lecturer, Department of Jurisprudence and International Law, Fac- ulty of Law, University of Lagos; E-mail: [email protected]. I am grateful to the two anonymous referees who reviewed and offered useful comments on the earlier draft of this article. 150 AFE BABALOLA UNIVERSITY: JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT LAW AND POLICY (2014) 3:1 1. INTRODUCTION orruption has become a fact of life in Nigeria, ravaging the country’s Csocio-political and economic sectors.1 Though corruption arguably ex- ists in every country, its effects, extent and magnitude