The Leading Edge—Thoughts and Memories Jonathan Langford, December 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFRA Newsletter 259/260

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 12-1-2002 SFRA ewN sletter 259/260 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 259/260 " (2002). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 76. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2Sfl60 SepUlec.JOOJ Coeditors: Chrlis.line "alins Shelley Rodrliao Nonfiction Reviews: Ed "eNnliah. fiction Reviews: PhliUp Snyder I .....HIS ISSUE: The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068- 395X) is published six times a year Notes from the Editors by the Science Fiction Research Christine Mains 2 Association (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale. For information about SFRA Business the SFRA and its benefits, see the New Officers 2 description at the back of this issue. President's Message 2 For a membership application, con tact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or Business Meeting 4 get one from the SFRA website: Secretary's Report 1 <www.sfraorg>. 2002 Award Speeches 8 SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage Inverviews submissions, including essays, review John Gregory Betancourt 21 essays that cover several related texts, Michael Stanton 24 and interviews. Please send submis 30 sions or queries to both coeditors. -

SF Commentarycommentary 80A80A

SFSF CommentaryCommentary 80A80A August 2010 SSCCAANNNNEERRSS 11999900––22000022 Doug Barbour Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Bruce Gillespie Paul Ewins Alan Stewart SF Commentary 80A August 2010 118 pages Scanners 1990–2002 Edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia as a supplement to SF Commentary 80, The 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 1, also published in August 2010. Email: [email protected] Available only as a PDF from Bill Burns’s site eFanzines.com. Download from http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC80A.pdf This is an orphan issue, comprising the four ‘Scanners’ columns that were not included in SF Commentary 77, then had to be deleted at the last moment from each of SFCs 78 and 79. Interested readers can find the fifth ‘Scanners’ column, by Colin Steele, in SF Commentary 77 (also downloadable from eFanzines.com). Colin Steele’s column returns in SF Commentary 81. This is the only issue of SF Commentary that will not also be published in a print edition. Those who want print copies of SF Commentary Nos 80, 81 and 82 (the combined 40th Anniversary Edition), should send money ($50, by cheque from Australia or by folding money from overseas), traded fanzines, letters of comment or written or artistic contributions. Thanks to Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) for providing the cover at short notice, as well as his explanatory notes. 2 CONTENTS 5 Ditmar: Dick Jenssen: ‘Alien’: the cover graphic Scanners Books written or edited by the following authors are reviewed by: 7 Bruce Gillespie David Lake :: Macdonald Daly :: Stephen Baxter :: Ian McDonald :: A. -

We Blazed Online

kfynS (Read ebook) We Blazed Online [kfynS.ebook] We Blazed Pdf Free David Farland audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2378027 in eBooks 2011-10-13 2011-10-13File Name: B005VT7D82 | File size: 17.Mb David Farland : We Blazed before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised We Blazed: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Thought-provokingBy P. J. ScottInteresting and thought-provoking short story, not at all what I expected but what speculative fiction should be.I will definitely be reading more from this author.Highly recommend.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. One of Farland's best short storiesBy Trent Walters"We Blazed" tells the story of two immortals who promised to love each other forever. The speculative conceit here initially feels familiar, but once Farland pushes it further, it gets intense. The ending seals the deal. The unicorn in the picture is more metaphorical than literal but it plays fairly well and helps make the story resonate for the reader.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Excellent short story! David got me reading fiction again. He is the true master of creating worlds....By C. JackThis story is an example why David Farland is so popular and so good. He understands how to craft a story that grabs you and drags you along...willingly. I couldn't put this one down until it was done. The imagery, the pace, the twists...it all works.David got me reading fiction again. -

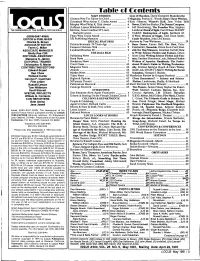

Table of Contents MAIN STORIES Lion of Macedon, David Gemmell; Mairelon the Gleason New Tor Editor-In-Chief

Table of Contents MAIN STORIES Lion of Macedon, David Gemmell; Mairelon the Gleason New Tor Editor-In-Chief.......................... 6 Magician, Patricia C. Wrede; Enter Three Witches, Greenland Wins A rthur C. Clarke Award ........... 6 Kate Gilmore; Wizard’s Hall, Jane Yolen; Hell- Murphy Wins Philip K. Dick Award ...................... 6 flower, Elukibes Shahar, The Dream Compass, Hoffman Leaves Waldenbooks................................ 6 Jeff Bredenberg; The Paradise War, Stephen THE NEWSPAPER OF THE SCIENCE FICTION FIELD Morrow, Avon Combine SF Lines; Lawhead; Hawk’s Flight, Carol Chase. SHORT Hartwell Leaves ..................................................... 7 TAKES: Redemption of Light, Kathleen M. (ISSN-0047-4959) Flynn Wins Crook Award ......................................... 7 O ’Neal; Mission of Magic, Julie Dean Smith; EDITOR & PUBLISHER UK Publishing M assacre........................................... 7 Castle Murders, John DeChancie. Charles N. Brown SPECIAL FEATURES Reviews by Tom Whitmore:....................................29 ASSOCIATE EDITOR Patricia Kennealy: 20 Years Ago ............................ 9 Bone Dance, Emma Bull; The Host, Peter Faren C. Miller Farmers Celebrate 5 0 th ............................................. 9 Emshwiller; Xenocide, Orson Scott Card; Out ASSOCIATE MANAGER Lundwall Reaches 5 0 ................................................. 9 side the Dog Museum, Jonathan Carroll; How Shelly Rae Clift THE DATA FILE to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy, Orson EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Publishing -

Speculative Fiction

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2013-1 Speculative Fiction J. Michael Hunter Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Fiction Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hunter, J. Michael, "Speculative Fiction" (2013). Faculty Publications. 1395. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/1395 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mormons and Popular Culture The Global Influence of an American Phenomenon Volume 2 Literature, Art, Media, Tourism, and Sports J. Michael Hunter, Editor Q PRAEGER AN IMPRINT OF ABC-CLIO, LLC Santa Barbara, Cal ifornia • Denver, Colorado • Oxford, England Copyright 2013 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mormons and popular culture : the global influence of an American phenomenon I J. Michael Hunter, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-39167-5 (alk. paper) - ISBN 978-0-313-39168-2 (ebook) 1. Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints-Influence. 2. Mormon Church Influence. 3. Popular culture-Religious aspects-Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. -

LTUE 26 = 2008 Cover

Acknowledgments As always, we would like to thank all those who have helped to make this symposium possible: BYU College of Humanities Life, the Universe, & Dean John Rosenberg • Zina Petersen BYU Humanities Publication Center BYU Bookstore, especially Anita Charles, Marilyn Johnson, and Everthin XXVI Lynn Blaser The Marion K. “Doc” Smith BYU Custodial Services • BYU Scheduling Office • BYU Travel Office The spouses, children, roomates, etc., of the symposium committee Symposium on Science Fiction and Fantasy Our guests, panelists, and volunteers And especially, all of you who come! See you next year! Orson Scott Card Deep Thoughts: Gail Carson Levine Proceedings of Life, the Universe, & Everything Kevin Wasden Each volume contains insights into sf&f literature and writing, including the main address of each guest of honor as well as the papers presented at the symposium. (Full contents are listed on ltue.byu.edu.) 1993: Kevin J. Anderson, Orson Scott Card, and Barbara Hambly 1994: Robert L. Forward, Katherine Kurtz, and Roger Zelazny 1995: Lois McMaster Bujold and Patricia A. McKillip 1996: Patricia C. Wrede and Dave Wolverton 1997: Judith Moffett 1998: Elizabeth Moon and Sherwood Smith February 14–16, 2008 1999: Kevin J. Anderson and Rebecca Moesta Brigham Young University To purchase Deep Thoughts, tell us which volumes you would like and send a check or money order for $9 per volume (includes postage) made payable to Life, the Universe, & Everything to: LTU&E Proceedings Volume 4087 JKB Provo, Utah, 84602 In Memoriam To those souls who touched our lives before bravely going into that great beyond Marion K. “Doc” Smith—A BYU professor of English for many years and the force behind the symposium. -

Accelerated Reader Test List Report

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value ----------------------------------------------------------------------- --- 31683EN The Birthday Present Mavis Smith 0.4 0.5 41850EN Clifford Makes a Friend Norman Bridwell 0.4 0.5 42156EN I Am Lost! Hans Wilhelm 0.4 0.5 31581EN We Play on a Rainy Day Angela Shelf Medea 0.4 0.5 60939EN Tiny Goes to the Library Cari Meister 0.5 0.5 74854EN Cooking with the Cat Bonnie Worth 0.6 0.5 42150EN Don't Cut My Hair! Hans Wilhelm 0.6 0.5 83081EN Hello, School Bus! Marjorie Blain Par 0.6 0.5 45501EN Honey Helps Laura Godwin 0.6 0.5 55667EN I Hate My Bow Hans Wilhelm 0.6 0.5 3051EN My Dog's the Best! Stephanie Calmenso 0.6 0.5 83514EN Puppy Mudge Finds a Friend Cynthia Rylant 0.6 0.5 59439EN Rosie's Walk Pat Hutchins 0.6 0.5 129710EN Uh-oh, Max Jon Scieszka 0.6 0.5 135353EN Big Friend, Little Friend Melissa Lagonegro 0.7 0.5 56413EN The Ear Book Al Perkins 0.7 0.5 44456EN Hungry Animals Deborah Eaton 0.7 0.5 65000EN I Love My Shadow! Hans Wilhelm 0.7 0.5 31613EN Itchy, Itchy Chicken Pox Grace Maccarone 0.7 0.5 27420EN Kites Bettina Ling 0.7 0.5 70788EN Puppy Mudge Takes a Bath Cynthia Rylant 0.7 0.5 58779EN Recess Mess Grace Maccarone 0.7 0.5 43663EN Biscuit Finds a Friend Alyssa Satin Capuc 0.8 0.5 135206EN Biscuit Meets the Class Pet Alyssa Satin Capuc 0.8 0.5 70783EN Biscuit's Big Friend Alyssa Satin Capuc 0.8 0.5 51892EN Counting Sheep: A Math Reader Julie Glass 0.8 0.5 41859EN I Have a Cold Grace Maccarone 0.8 0.5 31710EN Mousetrap Diane Snowball 0.8 0.5 44324EN The Secret Friend Marcia Vaughan 0.8 0.5 126524EN Snow Trucking! Jon Scieszka 0.8 0.5 133152EN Stuck in the Mud W. -

The Mooncalfe Online

yiMmZ (Ebook pdf) The Mooncalfe Online [yiMmZ.ebook] The Mooncalfe Pdf Free David Farland DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1903593 in eBooks 2011-10-22 2011-10-22File Name: B005YQB7KC | File size: 19.Mb David Farland : The Mooncalfe before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Mooncalfe: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. A Side Story of the Arthurian LegendBy TankA well-told tale of the Arthurian legend, told from a different viewpoint. The story centers around Uther's rape of Arthur's mother while pretending to be her husband (with the help of a little magic). But after that, Uther disappears from the story and it revolves around the girl child of another casualty of the encounter. Yes, Merlin is in the story.What I liked most of all is that the story sticks to the ORIGINAL legend, rather than all the claptrap spinoffs that have surfaced in the last few decades. It's well-written with few typos (but could have used another pair of eyes). The ending is a nice surprise.It's a novelette, but I wish it were longer. Well done!0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Excellent Arthurian Short StoryBy AngusThe Mooncalfe is a novella and the name of the child of Merlin. This story is so short that I donrsquo;t want to go into much detail as it might spoil it for you. Quick overview because most of you know the tale. -

James Dashner Steve Keele

Acknowledgments As always, we would like to thank all those who have helped to make this symposium possible: BYU Conference Center staff Rodger D. Sorensen • Eric Fielding BYU Humanities Publication Center • Mel Thorne BYU Bookstore, especially Tami Barber The spouses, children, roomates, etc., of the symposium committee Our guests, panelists, and volunteers And especially, all of you who come! See you next year! Deep Thoughts: Proceedings of Life, the Universe, & Everything Each volume contains insights into sf&f literature and writing, including the main address of guests of honor as well as the papers presented at the symposium. (Full contents are listed on ltue.org.) 1993: Kevin J. Anderson, Orson Scott Card, and Barbara Hambly 1994: Robert L. Forward, Katherine Kurtz, and Roger Zelazny 1995: Lois McMaster Bujold and Patricia A. McKillip 1996: Patricia C. Wrede and Dave Wolverton 1997: Judith Moffett 1998: Elizabeth Moon and Sherwood Smith 1999: Kevin J. Anderson and Rebecca Moesta 2000: L. E. Modesitt Jr. Guests of Honor: To purchase Deep Thoughts, tell us which volumes you would like and send a check or money order for $10 per volume (includes postage) made payable to Life, the Universe, & Everything to: James Dashner LTU&E Proceedings Volume 4087 JKB Provo, Utah, 84602 Steve Keele In Memoriam Committee Awards To those souls who touched our lives before bravely going into that great beyond There are many people who work very hard to make the symposium happen. We ask your indulgence at our closing ceremonies, whatever they may be, as we pay tribute Marion K. “Doc” Smith—a BYU professor of to these overworked volunteers who have gone above and beyond the call of duty. -

REVIEWS a Survey of Mainstream Children's Books by LDS Authors. Reviewed by Stacy Whitman, an Editor at Mirrorstone, Which

REVIEWS A Survey of Mainstream Children’s Books by LDS Authors. Reviewed by Stacy Whitman, an editor at Mirrorstone, which publishes fantasy for children and young adults. She holds a master’s degree in children’s literature from Simmons College. A slightly modified version of this review was posted on By Common Consent, December 20, 2007 {http://www.bycommonconsent. com}. If you’re at all familiar with literary talk these days, you might be aware of the chatter about children’s and young adult literature1 being the hot new thing. Everyone’s wondering what will be the “next Harry Potter.” What was once a ghettoized field of study—because children are a self-perpetuat- ing lower class, and literature for children must therefore serve a purpose (teach a lesson or make kids get good grades)—is now legitimate at many institutes of higher learning. Adults are getting reading recommendations from children and teens, and vice versa. Despite frenzied reports to the contrary, reading is not dead among the younger set. When people ask what I do for a living, invariably the reaction to my answer—that I’m a children’s book editor—is “how exciting!”—espe- cially when I say that I edit children’s and young adult fantasy novels. It is exciting. We’re living in a golden age of children’s and young adult litera- ture, full of breathtaking storytelling and artistry. And some of the leading names in this golden age are authors who happen to be Mormons. When I read submissions at work, any variation on “the moral of this story is . -

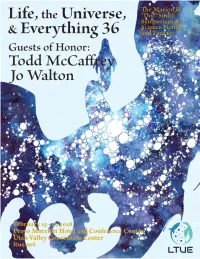

Mass Book Signing 33 Grid Schedule 22 Acknowledgments 42

Letter from the Chair Dearest LTUE-ians, Another Presidents’ Day weekend is upon us, and I am thrilled that I get to spend it with you. A few years ago, I took a job out of state in possibly the least bookish and un-nerdiest city ever. After living in a town that recently announced its new mayor with a Star Wars parody, I found myself alone. I didn’t feel like I had much in common with anyone. I struggled to connect with people, and I began to wonder if maybe I was delusional for thinking that anyone else might like dragons, monsters, and spaceships. But every year, I made the trek back to Utah, and every year, I was delighted to rediscover my people. People who love to read, write, draw, and game all kinds of lovely weirdness. You, you glorious land mermaids, gave me hope. You gave me a place, and for that, I am everlastingly grateful. I hope that you too find friends old and new this year at LTUE. Flash forward to this year, and as chair, the LTUE community came through for me once again. Nothing would have been possible without the LTUE committee behind me. Every panel, poster, and pancake here crawled out of the brain of one of our volunteers, and I am honored to work with such talented and dedicated individuals. I especially want to thank Kate for raising the bar on all fronts, Jenna for being willing to tame a monster of a track, Kevin for putting up with our eccentricities, Mike for pulling order from chaos, and Elizabeth D. -

Locus, May 2015

T A B L E o f C O N T E N T S May 2015 • Issue 652 • Vol. 74 • No. 5 48th Year of Publication • 30-Time Hugo Winner CHARLES N. BROWN Founder (1968-2009) Cover and Interview Designs by Francesca Myman LIZA GROEN TROMBI Editor-in-Chief KIRSTEN GONG-WONG Managing Editor MARK R. KELLY Locus Online Editor-in-Chief CAROLYN F. CUSHMAN TIM PRATT Senior Editors FRANCESCA MYMAN Design Editor ARLEY SORG Editorial Assistant JONATHAN STRAHAN Reviews Editor TERRY BISSON LIZ BOURKE CORY DOCTOROW GARDNER DOZOIS STEFAN DZIEMIANOWICZ RICH HORTON Ellen Datlow and Joe Haldeman fishing off the pier at ICFA RUSSELL LETSON I N T E R V I E W RICHARD A. LUPOFF FAREN MILLER Nnedi Okorafor: Magical Futurism / 6 COLLEEN MONDOR Ken Liu: Silkpunk / 58 TOM WHITMORE GARY K. WOLFE C O N V E N T I O N S Contributing Editors Willliamson Lectureship: April 9-11, 2015 / 4 2015 Writers and Illustrators of the Future / 5 ALVARO ZINOS-AMARO 2015 International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts / 32 Norwescon 38 / 57 Roundtable Blog Editor WILLIAM G. CONTENTO M A I N S T O R I E S / 5 & 10 Computer Projects Locus, The Magazine of the Science Fiction & Fantasy 2015 Hugo Awards Ballot • Elison Wins Dick Award • 2014 BSFA Awards Winners • Russ Field (ISSN 0047-4959), is published monthly, at $7.50 per copy, by Locus Publications, 34 Ridgewood Lane, Oakland and Schmidt Win Solstice Awards • Byrne and Walton Win Tiptree • Dell Awards Winners • CA 94611. Please send all mail to: Locus Publications, PO Box 13305, Oakland CA 94661.